Introduction

Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) are an umbrella term for a wide range of conditions that result in reduced blood flow to the heart muscle, resulting in a medical emergency. These include heart attacks, with three primary forms of ACS encompassing ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and unstable angina (NHS, 2019). The case study which will be the primary focus of this paper presents a patient with a diagnosis of STEMI, as a consequence of both poor lifestyle factors as well as family medical history putting him at risk. The paper will include sections covering the pathophysiology of the condition, nursing care and management processes, and a contemporary nursing issue related to the scenario.

Pathophysiology

From a pathophysiological perspective, acute myocardial infarction (MI) is defined as a cardiomyocyte death due to prolonged ischaemia which occurs due to an imbalance between oxygen supply and demand (Montecucco, Carbone and Schindler, 2015). For an acute thrombotic coronary occurrence to cause ST-segment elevation, it requires significant and continuous blockage of blood flow. Coronary atherosclerosis and evidence of high-risk thin cap fibroatheroma (TCFA) can lead to sudden onset plaque rupture. The modifications in the vascular endothelium stimulate platelet adhesion, activation and aggregation, creating thrombosis formation.

Models demonstrate that myocardial injury spreads to from the sub-endocardial myocardium to the sub-epicardial myocardium which is demonstrated by the transmural infarction that appears as ST elevation. Myocardial damage begins immediately as blood flow is stopped otherwise the acute ischemia will result in severe microvascular dysfunction (Akbar, Foth, Kahloon and Mountfort, 2020). For those who survive STEMI, the infarcted muscle is replaced with scar tissue known as fibrosis which impacts the ability of the heart to function and can serve as a determinant of heart failure and long-term survival (NHS, 2019).

The underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes originate with atherosclerosis, which can begin to develop decades prior to the acute event. Atherosclerosis is a low-grade inflammatory state of the intima or medium-sized arteries. The inflammation is exacerbated by evident risk factors such as diabetes, smoking, genetics, high blood pressure, and cholesterol. These lead to gradual thickening of the intima of the arteries and narrow its lumen.

The atherosclerotic progression can be interrupted by a rapid progression event related to two processes, either the asymptomatic plaque disruption or plaque haemorrhage (Ambrose and Singh, 2015). Occurrence and onset of acute MI is unpredictable. A clinical correlate of ischaemic preconditioning is pre-infarction angina which has been associated with reduced infarct size and coronary microvascular injury (Heusch and Gersh, 2016).

The modern pathophysiological paradigm views acute MI as a ‘perfect storm’ of events where coronary arterial stimuli for thrombosis overlaps a “pro-thrombotic milieu” at the location of the plaque rupture or erosion (Montecucco, Carbone and Schindler, 2015). Generally, TCFA is considered to be a higher risk of rupture, however associations with MI may not be definite. A 697-patient study for 3 years observing cardiovascular events noted that there are cycles of plaque rupturing and healing as frequent events that contribute to the coronary narrowing or modifying the morphology of the plaque without symptoms being present.

The transition to a symptomatic plaque rupture includes a minority of severe vulnerable plaques that rapidly progress in the weeks prior to the MI event. High luminal stenosis is associated with atherosclerotic burden, that justifies the high rate of the MI event rather than stenosis itself. A study by Buffon et al. challenged the notion of a single vulnerable plaque, suggesting that widespread coronary inflammation is independent of the location of the culprit legion, with intraplaque inflammation critical to atherogenesis and plaque evolution (Montecucco, Carbone and Schindler, 2015).

The pathophysiology of acute MI differs depending on the type. AMI can be categorized based on ECG into ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) (Ambrose and Singh, 2015). STEMI is a subset of acute MI due to rupture or erosion of an atherosclerotic plaque with thrombotic occlusion of an epicardial coronary artery and transmural ischaemia (Heusch and Gersh, 2016). The resulting size of the infarction depends on three factors such as the size of the ischaemic area at risk, duration of the coronary occlusion, and significance of collateral blood flow combined with the extent of microvascular dysfunction (Heusch and Gersh, 2016).

STEMI presents commonly with complete coronary occlusion and a level of myocardial necrosis (or risk of it) is larger than NSTEMI. Although the NSTEMI coronary occlusion is lower, but with the artery lumen not fully obstructed, there is commonly a severe blockage present in one or more arteries with an intraluminal coronary thrombus. In trials, the use of ocular coherence tomography to evaluate intraluminal pathology showed that plaque rupture is seen in 72% of STEMI cases and 32% NSTEMI, while plaque erosion is visible in 28% of STEMI and 48% NSTEMI (Ambrose and Singh, 2015).

Therefore, there are three primary vascular events which can cause coronary thrombosis that leads to STEMI, those being plaque rupture, plaque erosion, and calcific nodules. Calcific nodules are the rarest, seen in 2-7% of patient, commonly seen in the right coronary artery (Holmes et al. 2013). The second most common is plaque erosion, with an incidence of 15-20% of STEMI cases, but as high as 40% in young populations. Plaque erosion is characterized by a neutral or negatively remodelled, thick cap fibroatheroma. Eroded plaques typically have abundant smooth muscle cells, with fewer macrophages and less calcification than other types.

A less stenotic lesion has been associated with erosion as well as no communication between the necrotic core and the lumen, with the atherosclerotic plaque potentially not being thrombogenic whatsoever (Holmes et al. 2013). Finally, the most common cause is plaque rupture seen in approximately 76% of STEMI cases. It can be characterized with a positively remodelled, thin cap fibroatheroma, with signs of increased inflammation and neovascularization. The macrophage-dependent matrix results in the rupture of the fibrous cap, which exposes the highly thrombogenic necrotic core to the lumen. The microphase-expressed tissue in the core results in thrombin generation and platelet activation creating occlusive atherothrombosis (Holmes et al. 2013).

Care and Management

Incidence of STEMI has decreased in the last two decades in developed countries, but mortality has increased despite widespread access to reperfusion therapy. This is due to development of heart failure in older populations. However, internationally, STEMI is both increasing while therapy is often inaccessible (Heusch and Gersh, 2016). The clinical definition of MI had been recently updated to focus on the values of serum markers of cardia necrosis, i.e. cardiac troponin (cTn). Patients that are presenting suspected acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergo clinical evaluation, 12-lead cardiogram, as well as measurements of cTnl to identify cardiomyocyte injury. An increase or decrease of cTn in the patient’s plasma, with at least one measurement >99th percentile of the upper normal indicators signifies MI, while the absence of such levels demonstrates unstable angina (Montecucco, Carbone and Schindler, 2015).

In cases of identified STEMI, emergency treatment is vital to restoring coronary perfusion, with the objective to limit the extent of damage to the myocardium and lowering risk of early death and long-term heart failure. Therefore, reperfusion strategies are the primary treatment for patients that are unconscious or experiencing cardiogenic shock (Carville, Henderson and Gray, 2015). The objective of treatment is to restore coronary blood supply known as reperfusion since myocardium begins to be lost as soon as blood supply is interrupted, resulting in long-term damage, with nearly half of the potentially salvageable muscle lost within 1 hour.

As soon as emergency services respond to the 999 call, fibrinolytic drugs can be administered intravenously by either the ambulance or emergency department staff (National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2013). An ECG should be applied immediately to evaluate the type of MI in the patient. Due to the high prevalence of coronary occlusions as well as potential challenges in interpreting the ECG, an urgent angiography should be considered for survivors of cardiac arrest (even if patient unresponsive) when there is a high probability or suspicion of an ongoing infarction (Ibanez et al., 2017).

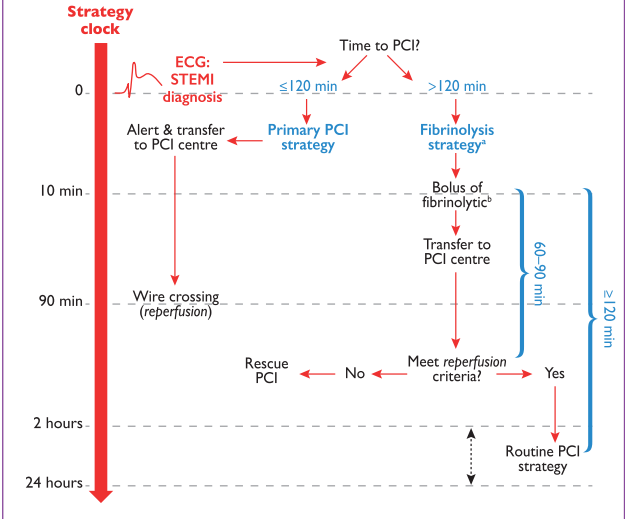

As seen in Figure 1 above, the timeline to delivering care management to diagnosed STEMI patients is vital. As discussed, PPCI is the preferred strategy in developed countries and urban areas where there is emergency access to cardia catheter laboratories. There is a general medical consensus that PPCI is both feasible and cost effective that it should be preferred treatment for STEMI (Carville, Henderson and Gray, 2015).

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is the most preferred reperfusion strategy for patients with STEMI given it is 12 hours of symptom onset and can be performed within 120 minutes of symptom onset by an experienced team including interventional cardiologists and skilled support staff. It is recommended by the NICE guidelines that the patient bypass the emergency room and is taken straight to the catheterisation laboratory. PPCI is an umbrella term which covers a wide variety of techniques to achieve reperfusion via either coronary angioplasty, thrombus extraction catheters or stenting (National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2013).

In cases where PPCI cannot be reasonably provided within the allocated time frame, a fibrinolysis treatment is recommended, similarly the earlier the better, but best within 12 hours of symptom onset. Fibrinolytic therapy is utilized to lyse acute blood clots via activation of plasminogen which generates plasmin that can split the fibrin cross-links, thus breaking down thrombus (Bahal et al., 2019). Fibrin-specific agents such as tenecteplase, alteplase, or reteplase are recommended.

It is also possible to utilize antiplatelet co-therapy with fibrinolysis treatment, such as oral/IV aspirin and clopidogrel. Sometimes, anticoagulation co-therapy is applied as well. As indicated in the timeline, the patient should be transferred to a PCI centre quickly. Emergency angiography and PCI are recommended for patients with heart failure and cardiogenic shock, and rescue PCI if fibrinolysis had failed. Angiography and PCI should be performed 2 to 24 hours after successful fibrinolysis (Ibanez et al., 2017).

Nursing care plays a critical role at practically stage of STEMI management and treatment. A nurse is commonly one of the first medical contacts of the patient. The time from symptom onset to reperfusion is vital to outcomes. Therefore, a nurse has the responsibility to identify acute MI and order an ECG, also being able to identify the STEMI on the ECG. A thorough physical examination alongside medical history if possible, should be undertaken as well. Ultimately, it is the nurse that decides if urgent reperfusion is necessary (Jarvis and Saman, 2017). The role of nurses in the treatment of STEMI by primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is essential for the success of the multidisciplinary team.

Once a decision is made regarding identifying STEMI, nurses contribute to the sharing of information with receiving physician and nurses and participating in the decision-making regarding further treatment. During PPCI, nurses can have a number of technical and supporting role ranging from administration of medication to anticipating and preventing complications. Nurses are vital, particularly in smaller healthcare settings to administering any treatments due to their high standard of knowledge, training, and experience in advanced medical procedures (Zughaft and Harnek, 2014).

Nursing care is also vital to element of long-term care, particularly providing guidance to the patient regarding lifestyle changes. As with the case such as the patient in the case study, lifestyle interventions will be necessary to avoid repetitive instances of acute MI or long-term complications such as heart failure or myocardial dysfunction (Ibanez et al., 2018). As part of multidisciplinary care and care management for the patient (discussed more in the next section), nurses would oversee vital cardiac rehabilitation for the patient, which is a key link between primary and secondary care.

Patients post-STEMI are offered guidance by nurses and other staff on lifestyle changes such as physical activity, diet, limiting/cessation of alcohol and smoking, and any other activities. At discharge patients are prescribed several medications, with nurses helping with optimisation of medication as well as providing patient education regarding medication adherence. Nursing care is also involved significantly in various elements of post-discharge and secondary care including potentially maintaining contact with the patient, participating in regular check-ups and guidance on maintaining adequate cholesterol and blood pressure (Warriner and Al-Matok, 2019). Overall, nursing care plays a critical supporting role in the management and treatment following an acute myocardial infarction.

Contemporary Issue

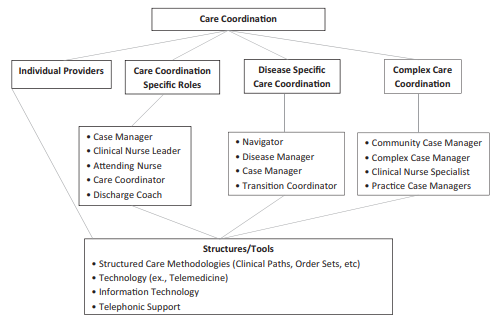

A relevant nursing issue that is applicable to this case study is care coordination. Care coordination is vital in complex treatments, such as for STEMI, where nurses must apply an effective care management system and competent use of available resources for optimal outcomes. Care coordination can be defined as a deliberate organization of patient care activities and exchange of information among all participants involved in the patient care to achieve a safer and more effective care.

This requires patient needs and preferences to be known and communication properly to the correct participants so that the information is utilized to provide safe, appropriate, and effective care (AHRQ, 2018). Coordinated care can be achieved through broad approaches such as teamwork, care management, medication management, and health information technology or specific care activities such as agreeing on responsibilities, communication, transition of care, creating a proactive care plan, monitoring and follow up, realigning resources and others (AHRQ, 2018).

Unfortunately, nurses typically spend only 15% of their shift engaged in care coordination activities which is a higher-level working function. Instead, the majority is spent on tasks that can be assumed by those with lesser level of education and licensure. Albeit it is difficult to determine the exact time that should be allocated, 15% of the time is not enough given that nurses are highly educated in facilitating patient self-care and disease management. Commonly, care coordination is reactive and disorganized instead of being planned which effectively decreases quality of care (Anderson, St. Hilaire and Flinter, 2012).

Coordination of care is not a new concept, particularly to licensed nurses. In the context of a partnership established between healthcare providers and patients or their families, nurses are vital to patient satisfaction and care quality. Patient-centred care coordination is a core professional standard and competency through overseeing efficient use of heath care resources, facilitating interprofessional collaboration and decreasing costs (Camicia et al., 2013).

Quality improvement and cost control ultimately rely on effective coordination overseen by nurses across the continuum of care. Greater healthcare efficiencies are realized through coordination of care focused on needs of the patients. Professional nursing links these approaches through promotion of quality, safety, and efficiency in care to achieve optimal outcomes as consistent with nursing’s holistic, patient-centred framework of care (Cropley and Sanders, 2013). The continuum of care in modern medicine is distinct from decades past as care coordination with its relationships and roles is absolutely vital to providing effective treatments. Nurses are at the epicentre of this process, developing strategies that align resources with patient and family needs through a myriad of activities which support patient progression and transition at all points of the continuum (Bower, 2016).

As seen in the case study, Jimmy underwent multiple transitions of care, ranging from emergency services to the cardiac catheterisation laboratory to the ICU to post-discharge secondary care and community cardia rehabilitation.

This is common for patients with such serious conditions, requiring optimal teamwork across professional groups and departments to achieve better clinical outcomes. Hospitals can enhance the effect of care pathway on teamwork by increasing support for quality improvement. Care coordination oversees the care pathways for STEI patients Care pathways are complex interventions that structure and organize care processes to enhance the quality of delivered care. Therefore, a model care pathway includes evidence-based key interventions and coordinates tasks efficiently across professional teams across departments (Aeyels et al. 2018).

Overall, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for management of STEMI patients encompass efforts to improve the speed and efficiency of provided care through care coordination (Steg et al., 2012). In the continuum of care, coordination has shown particularly positive outcomes and cost savings for patients transitioning from acute care to home. Patients with STEMI typically face multiple comorbidities and certain vulnerable populations cane be at increased risk of errors in post-discharge care or adherence to recommendations after the transition to home (Camicia et al., 2013).

Thus, according to these competencies of care coordination, discharge planning should begin when the patient is admitted. Nurses in care coordination oversee that patients and caregivers have a good understanding of medications, lifestyle changes and appropriately schedule follow-up appointments with the hospital or other care providers. In addition to acute rehabilitation, patients benefit from coordination of rehabilitation for secondary prevention of repetitive MI events (Chang and Rising, 2014).

Conclusion

Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) are a range of emergency conditions which result in limited blood flow to the heart. This paper focused specifically on ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) caused primarily by plaque erosion or plaque rupture due to multiple underlying causes. Management of STEMI consists of providing emergency care quickly, including identifying the condition on an ECG and the preferred method of treatment is a primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI).

Nurses play a significant role at all stages of care ranging from receiving the patient and identification of STEMI to treatment provision as support staff as well as critical participation in recovery and secondary treatment. A contemporary nursing issue that was selected for this is care coordination, where in complex treatments such as for STEMI, nurses must apply an effective care management system and competent use of available resources for optimal outcomes.

Reference List

Akbar, H., Foth, C., Kahloon, R.A. and Mountfort, S. (2020) Acute ST elevation myocardial infarction. Web.

Ambrose, J. and Singh, M. (2015) ‘Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease leading to acute coronary syndromes.’ F1000Prime Reports, 7(8). Web.

AHRQ. (2018) Care coordination. Web.

Anderson, D. R., St. Hilaire, D. and Flinter, M. (2012) ‘Primary care nursing role and care coordination: an observational study of nursing work in a community health center.’ The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 17(2). Web.

Aeyels, D., Bruyneel, L., Seys, D., Sinnaeve, P.R., Sermeus, W., Panella, M. and Vanhaecht, K. (2018) ‘Better hospital context increases success of care pathway implementation on achieving greater teamwork: a multicenter study on STEMI care.’ International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 31(6), pp.442–448. Web.

Bahall, M., Seemungal, T., Khan, K. and Legall, G. (2019) ‘Medical care of acute myocardial infarction patients in a resource limiting country, Trinidad: a cross-sectional retrospective study.’ BMC Health Services Research, 19(1). Web.

Bower, K.A. (2016) ‘Nursing leadership and care coordination.’ Nursing Administration Quarterly, 40(2), pp.98–102. Web.

Carmicia, M. et al. (2013) ‘The value of nursing care coordination: A white paper of the American Nurses Association.’ Nursing Outlook, 61(6), pp.490–501. Web.

Carville, S.F., Henderson, R. and Gray, H. (2015) ‘The acute management of ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction.’ Clinical Medicine, 15(4), pp.362–367. Web.

Chang, A.M. and Rising, K.L. (2014) ‘Cardiovascular admissions, readmissions, and transitions of care.’ Current Emergency and Hospital Medicine Reports, 2(1), pp.45–51. Web.

Cropley, S. and Sanders, E.D. (2013) ‘Care coordination and the essential role of the nurse.’ Creative Nursing, 19(4), pp.189–194. Web.

Heusch, G. and Gersh, B.J. (2016) ‘The pathophysiology of acute myocardial infarction and strategies of protection beyond reperfusion: a continual challenge.’ European Heart Journal, 38(11), pp.774-784. Web.

Holmes, D.R., Lerman, A., Moreno, P.R., King, S.B. and Sharma, S.K. (2013) ‘Diagnosis and management of STEMI arising from plaque erosion.’ JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging, 6(3), pp.290–296. Web.

Ibanez, B. et al. (2018) ‘2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation.’ European Heart Journal, 39(2), pp.119–177. Web.

Jarvin, S. and Saman, S. (2017) ‘Diagnosis, management and nursing care in acute coronary syndrome.’ Nursing Times, 113(3), pp.31-35. Web.

Montecucco, F., Carbone, F. and Schindler, T.H. (2015) ‘Pathophysiology of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: novel mechanisms and treatments.’ European Heart Journal, 37(16), pp.1268–1283. Web.

National Clinical Guideline Centre. (2013) Myocardial infarction with ST-segment-elevation. Web.

NHS. (2019) Diagnosis: heart attack. Web.

Steg, G. et al. (2012) ‘ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).’ European Heart Journal. Web.

Warriner, D. and Al-Matok, M. (2019) ‘Primary care management following an acute myocardial infarction’, Independent Nurse. Web.

Zughaft, D. and Harnek, J. (2014) ‘A review of the role of nurses and technicians in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).’ EuroIntervention, 10, pp.83–86. Web.