Introduction

We are “Red Panda,” a mammalian species native to southwestern China and the eastern Himalayas (see Appendix 1). We are the only members of the Ailuridae family (we could have been raccoons but scientists opted to place us in a separate family). We live both in the wild and in captivity (longer in captivity than in the wild). Those of us in the wild are about 10,000 individuals, which is why on the IUCN Red List, we are an “Endangered” species. Unfortunately, our numbers in the wild continue to decline due to fragmentation and habitat loss (Spaulding, 2015). Our numbers are also negatively affected by inbreeding depression and poaching. On average, males in our species weigh between 3.7 and 6.2 kilograms while females weigh between 3 and 6 kilograms. In the early 1990s, we were recognized as the state animal of Sikkim, India. We have also served as the mascot of the Darjeeling Tea Festival.

Description of the Red Panda

We have a reddish-brown coating and fluffy tails. Our bodies contain white, red, and blackish markings. Most of the white marks can be found in our round heads and faces. We also have pointed ears and short snouts. On average, we measure about 40 inches from the head to the tail. Individually, we possess 36 to 38 teeth and lack the first upper premolar; the lower one may be vestigial or absent. Our dental formula is i 3/3, c 1/1, p 3/3-4, m 2/2 (Thapa, Hu, & Wei, 2018). Because we are carnivores and like shoots and bamboo trees, our mandibles are quite robust (our jaws are wide and our teeth strong). We also have modified wrists that help us grasp bamboo stems and tree branches. Our larynx features reduced cartilages making them resemble those of the procyonids.

Lifespan

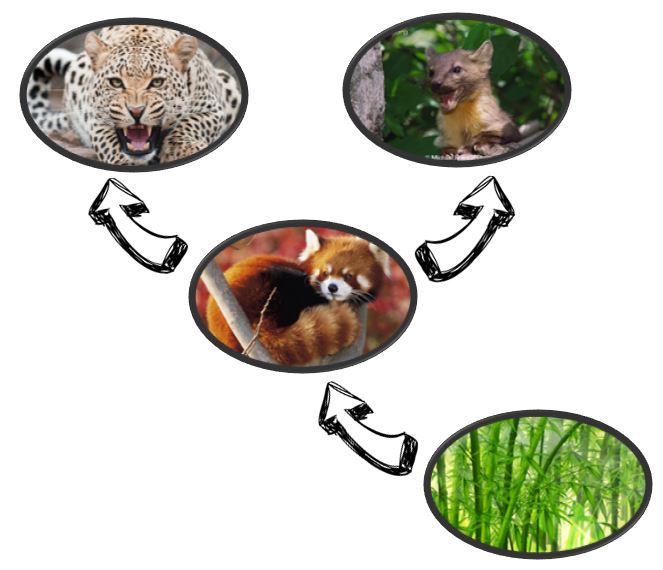

Our lifespan is about eight years with a gestation period of 145 days. Newborn cubs have sealed eyes for three weeks and remain in their mother’s care for up to 22 weeks (Spaulding, 2015). At 18 to 20 months, the cubs reach maturity. Most of our female counterparts give birth to twins; a few of them give birth to one or up to four cubs at a time. We prefer to live in high-altitude areas where plenty of bamboo trees grow. Bamboo is our favorite food. But we can also eat other plants, insects, and eggs. We eat up to two kilograms of bamboo daily, but we only digest 24 percent of it (Thapa et al., 2018). We are so similar that at first, scientists thought we belonged to the raccoon family. Later, they realized that we are closely related to the giant panda. We communicate using twitters, squeals, whistles, and body language. Our primary predators are wild dogs and leopards (See Appendix 2).

Habits

We are most active at night, dawn, and dusk spent most of our time in trees, and groom ourselves like cats. That is, we lick our front paws (like cats) and use them to wipe our furry bodies. At the base of our tails is a gland that we use to produce a strong odor to scare predators, just like skunks do. We can also stand on our rear feet and strike using our front claws, which are semi-retractable (Spaulding, 2015). Although we are the size of a big house cat, we have defensive mechanisms that scare large predators. Generally, we live solitary lives (see Appendix 3). Also, our males are highly territorial. When sleeping (during the day when it is cold), we cover ourselves with our fluffy tails to keep warm; we may become dormant if our body temperatures drop significantly. Some scientists studying our history noted that our population declined by 50 percent in the past 18 years (Thapa et al., 2018). We believe that deforestation and hunting contributed to the drastic decline in our numbers.

Features

Our features are well-suited (adapted) to the environment in which we live. For example, our thick fur helps us stay warm in the temperate mountain forests on the slopes of the Himalayas (Spaulding, 2015). They also help us stay warm in our other habitats situated in different parts of Asia. Our strong jaws and teeth make it easy for us to crush bamboo stems, which form up to 95 percent of our diet. Our wrists are also curved making it easy for us to grasp at a bamboo stem and feat on it the same way humans might eat sugar canes (Spaulding, 2015). These wrists also simplify tree climbing for us. Because we live in forests, we have retractable claws for protection and a gland that produces a strong scent to scare away predators. Since we are an endangered species, we try to avoid further problems by giving birth to many offspring; most of our females get twins. We have also started to eat a diverse range of vegetation as bamboo trees become scarce.

Adaptation

Our adaptation has contributed immensely to our relative success as a species. We believe that we have the willingness and ability to continue living. We avoid danger as much as possible; we eat only what the body likes and avoid unnecessary confrontations (Thapa et al., 2018). For this reason, we minimize the chances of dying from disease and injury. Although we are largely solitary, we value companionship occasionally, especially during the mating season. This ensures that our offspring are healthy. Our females stay in the birthing den with the newborn cubs for up to 90 days, and this increases the cubs’ chances of survival. When foraging, we are most active in darkness; at night, dusk, and dawn. We believe that these are the best times to look for food because our predators will be inactive. During the day, we sleep and stay in hiding for our safety. For this reason, we have survived for many years and hope to continue doing so for many more.

Impact of human activities

For the period that we have been alive, human activities have impacted our lives both positively and negatively. Human activities that have impacted our lives negatively include poaching, deforestation, and land-use changes (Thapa et al., 2018). Some of these activities have reduced the size of our natural habitats while others have caused numerous direct deaths to our species. For example, logging and the spread of agriculture have led to a decrease in the size of our habitats. Similarly, poaching has occasioned the death of many members of our family. Even so, we are resilient and continue to adapt to these significant changes. On the positive side, some human activities have facilitated our continued survival and have slowed down our decline. For example, zoos around the world give us protection and easy life. Some countries like China, India, Nepal, and Bhutan have protected areas reserved for us (Thapa et al., 2018). 35, 20, 8, and 5 protected areas (reserved for our us) can be found in China, India, Nepal, and Bhutan respectively. Such an effort should continue as it increases the chances of our survival as an endangered species.

References

Spaulding, M. (2015). The red panda: The first, not the lesser, of the pandas. Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 22(1), 123-124.

Thapa, A., Hu, Y., & Wei, F. (2018). The endangered red panda (Ailurus fulgens): Ecology and conservation approaches across the entire range. Biological Conservation, 220(5), 112-121.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Taxonomic Classification (Domain Through Species)

Appendix 2: Food Web Figure

Appendix 3: Haiku

I am me, a proud foodie, sometimes

Sleepy, odd at night, but pretty.

Red panda, I am, all around friendly