Medium

The chosen medium for this assignment is “A Litany for Survival” by Audre Lorde (1997):

For those of us who live at the shoreline

standing upon the constant edges of decision

crucial and alone

for those of us who cannot indulge

the passing dreams of choice

who love in doorways coming and going

in the hours between dawns

looking inward and outward

at once before and after

seeking a now that can breed

futures

like bread in our children’s mouths

so their dreams will not reflect

the death of ours;

For those of us

who were imprinted with fear

like a faint line in the center of our foreheads

learning to be afraid with our mother’s milk

for by this weapon

this illusion of some safety to be found

the heavy-footed hoped to silence us

For all of us

this instant and this triumph

We were never meant to survive.

And when the sun rises we are afraid

it might not remain

when the sun sets we are afraid

it might not rise in the morning

when our stomachs are full we are afraid

of indigestion

when our stomachs are empty we are afraid

we may never eat again

when we are loved we are afraid

love will vanish

when we are alone we are afraid

love will never return

and when we speak we are afraid

our words will not be heard

nor welcomed

but when we are silent

we are still afraid

So it is better to speak

remembering

we were never meant to survive.

Synthesis

Introduction of Harro’s Models

Cycle of Socialization

A conceptual framework known as Harro’s Cycle of Socialization aims to clarify the complex process by which people form their social identities within a particular culture. This model discusses societal factors that influence how one forms one’s beliefs, values, and attitudes. Fundamentally, the cycle shows how socialization is a lifelong process that a person goes through from birth to adulthood, specifically focusing on the influence of social structures on an individual’s sense of self (Harro, 2010b). Initially, each person is a blank slate; the model attempts to show the external influences of family, peers, the media, and institutions (Harro, 2010b). Outside influences form a person’s early views and opinions. These outside factors are internalized and serve as the foundation for the development of their social identities.

The model goes on to explore the domain of both interpersonal and institutional discrimination. Societal institutions uphold social hierarchies and power structures that currently exist. These institutions—political, economic, or educational—become channels through which societal norms that either support or undermine preexisting inequality are transmitted (Harro, 2010b). Still, interpersonal interactions that take place within these institutions also play a role in either reinforcing or changing the attitudes and beliefs of individuals.

The cycle’s next step investigates how internalized biases affect a person’s behavior and worldview. The results of being coerced into upholding the cycle of discrimination are inequality, oppression, isolation, misunderstandings, and dispossession (Harro, 2010b). An individual’s interactions within different social contexts are shaped by the internalization of societal prejudices. Fittingly, the final step of the model has two branches; the individual has the choice to either continue upholding the status quo or to change (Harro, 2010b). It is a call to action that asks the reader to employ critical self-reflection and conscientization. Although personal identity is always influenced by societal structures, individuals are not deprived of agency; they can take an active part in confronting and changing oppressive norms. There is the possibility of awareness-based empowerment, motivating people to become change agents in their local communities.

Cycle of Liberation

Harro’s Cycle of Liberation follows the ground built by the Cycle of Socialization. This theoretical framework outlines the stages people traverse in their pursuit of social justice and liberation. The cycle begins with the moment when individuals become aware of the existence of systemic oppression for the first time (Harro, 2010a). However, few are able to immediately; there is a stage for preparation, gaining the skills and information required to successfully negotiate the difficulties of social justice activism (Harro, 2010a). Setting the stage for the upcoming journey towards liberation makes this stage extremely important.

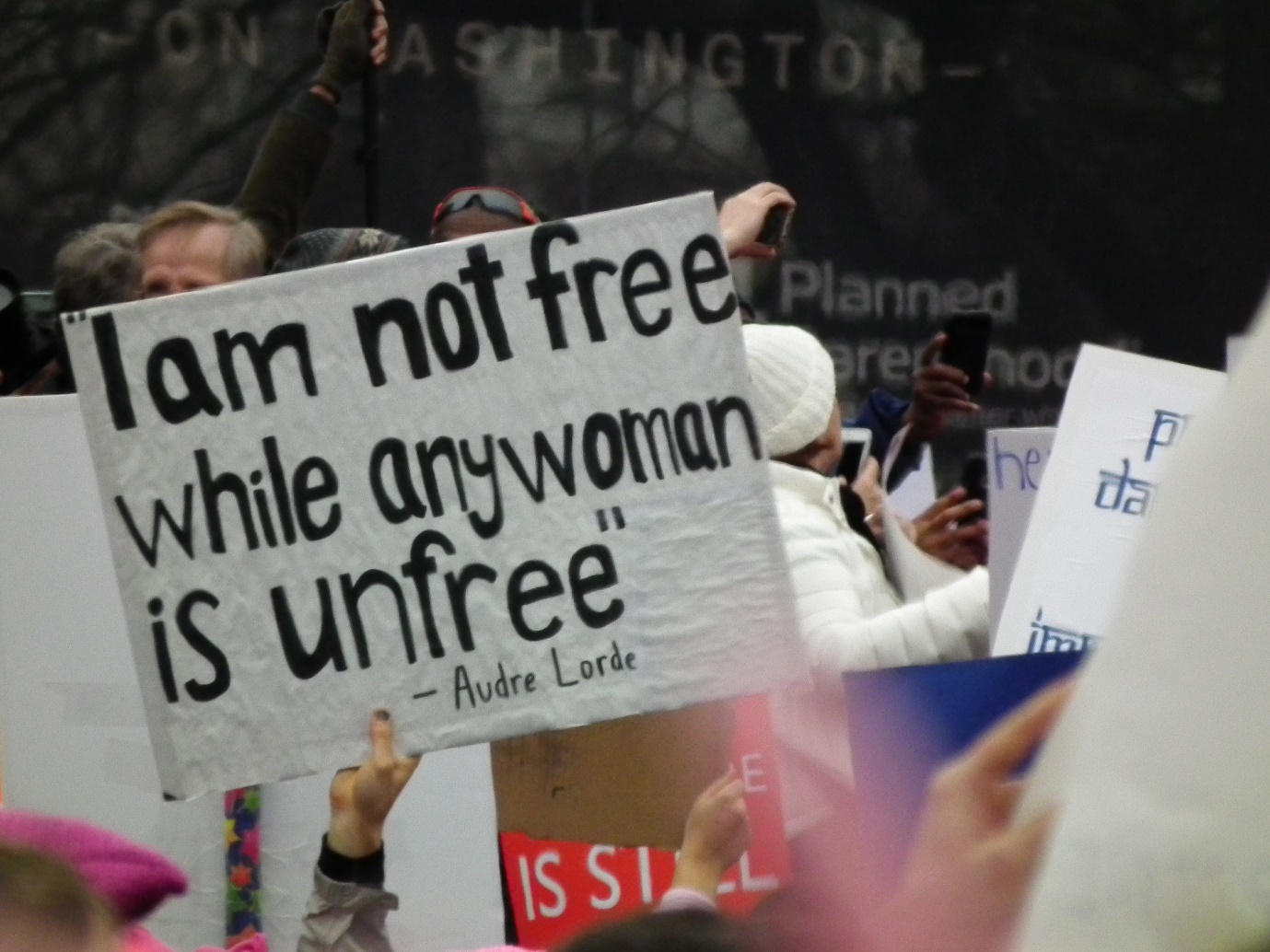

Once they are ready, individuals reach out to other like-minded entities. Through encouraging a common purpose, this outreach plays a crucial role in creating a collective force against oppressive structures (Harro, 2010a). The next step focuses on creating a resilient network of support, offering a forum for the sharing of concepts, tactics, and experiences (see Figure 1). The momentum of the liberation process depends critically on the strength of this community. The movement coalesces, and divergent efforts come together to form a cohesive force (Harro, 2010a). This stage is the coming together of different voices to form a stronger force that can actually bring about significant change.

Oppressive structures are deliberately challenged and transformed by the strategic application of the collective power gathered. With the support of their united front, activists strive to eliminate systemic injustices and create a more equitable social structure (Harro, 2010a). After the transformative phase, the cycle ends with the maintenance of the new order (Harro, 2010a). Continued efforts are required to protect the accomplished changes; the fight for liberation is ongoing, and it is crucial to remain vigilant, flexible and to keep working as a group.

Medium Analysis

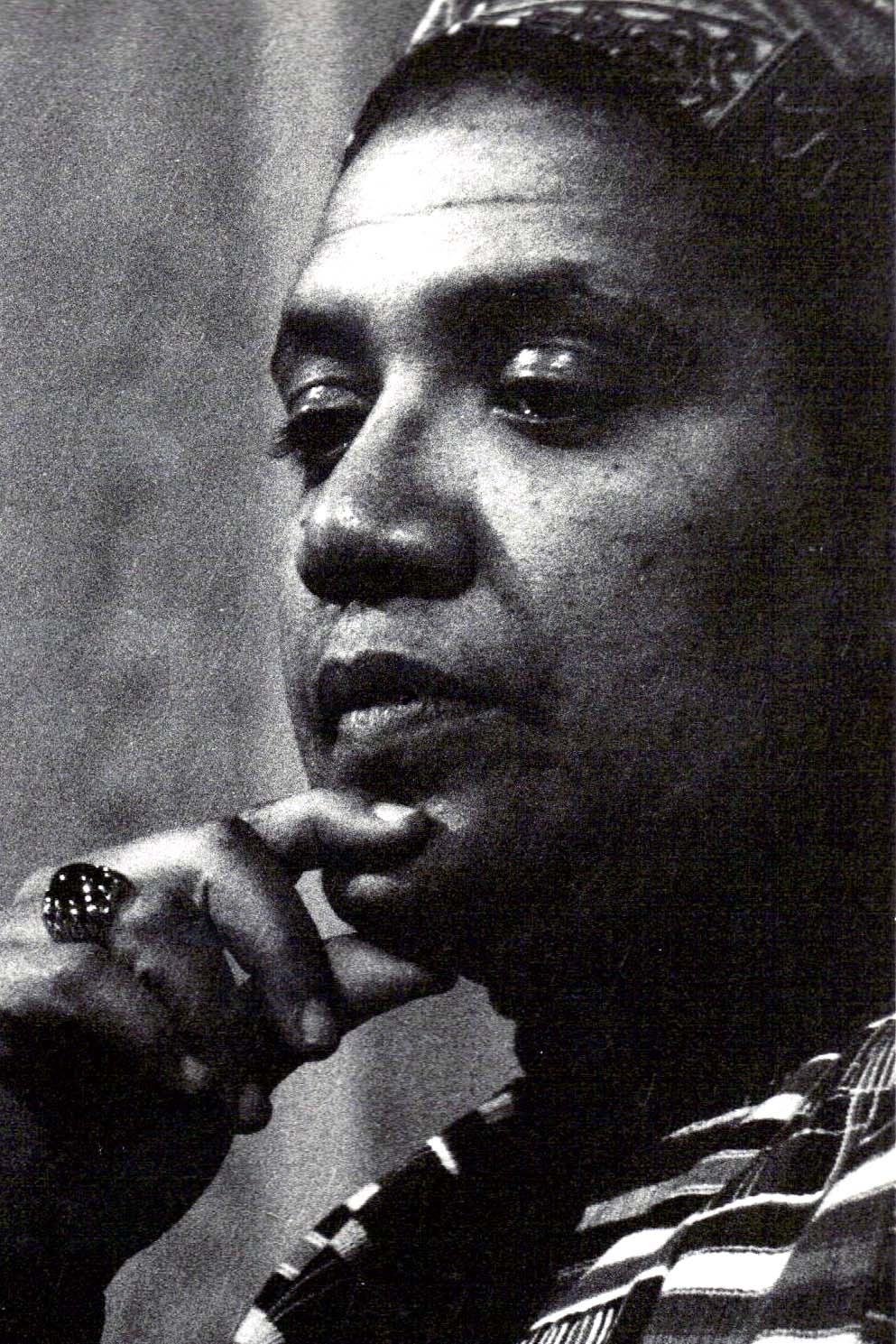

“A Litany for Survival” by Black feminist poet Audre Lorde focuses on the struggles that marginalized people face (see Figure 2). A close reading shows it has a strong resonance with both Harro’s Cycle of Socialization and the Cycle of Liberation. At the core of Harro’s Cycle of Socialization lies fear; Lorde’s poem also centers on the scars of fear that people carry from their earliest experiences (Harro, 2010b).

According to Lorde (1997), this fear is “like a faint line in the center of our foreheads” (p. 255), emphasizing how ingrained fear is in the lives of marginalized people. The statement that “mother’s milk” taught oppressed individuals to be afraid is a symbol of how early this socialization was (Lorde, 1997, p. 255). The poem then illustrates the idea of institutional and cultural socialization with allusions to the “passing dreams of choice” that certain people are unable to fulfill (Lorde, 1997, p. 255). Cultural norms and societal structures restrict the options open to some people.

Other than referring to the core and first stages of Harro’s model, Lorde’s poem can be seen as a depiction of the rest of the cycle. In particular, Lorde’s (1997) fear of the “heavy-footed” (p. 255) refers to the enforcement stage of the socialization cycle, which is when discriminatory practices are sustained and perpetuated, intending to silence those who question the status quo (Harro, 2010b). As such, Lorde’s poem offers a moving examination of the internal and external forces that mold people and societies.

Being a litany, the poem captures the spirit of Harro’s Cycle of Liberation at the same time. “Speak / remembering / we were never meant to survive” (Lorde, 1997, p. 256) is a call that corresponds with the Liberation Cycle’s awakening stage (Harro, 2010a). It is an understanding of the necessity of challenging the current power structures and escaping the confines of societal expectations. Lorde speaks up in the face of fear, and this reflects the Liberation Cycle’s narrative, inviting individuals to challenge, inform, and reinterpret accepted narratives. Lorde’s (1997) words can be applied to other phases of liberation: “looking inward and outward / at once before and after” (p. 255) alludes to the personal transformation people must go through in order to obtain change. These lines, combined with the persistent use of the “we” pronoun, convey shared desires and fears, proving the collective nature of the struggle and implying a discussion of community and solidarity.

Developmental Theories

The poem discusses fear and the various ways people manage and overcome it. Repression, denial, and projection—three of Freud’s defense mechanisms—can be understood as psychological tactics people use to cope with the fear that has been ingrained in them (Defense mechanisms, n.d.). As an example, the fear that is “like a faint line in the center of our foreheads” alludes to a psychological defense mechanism in which people may suppress or deny their fears unintentionally in order to deal with life’s challenges (Lorde, 1997, p. 255).

Furthermore, defensive strategies like sublimation and suppression can be connected to anxiety about speaking up and the possible repercussions of expressing oneself. As the poem suggests, speaking up in the face of fear may require making a deliberate effort to get past these barriers, which can promote empowerment—especially if the individual is marginalized.

Another perspective through which Lorde’s poem can be discussed is the work of James Marcia. According to Marcia’s theory, there are four different identity statuses depending on whether or not a person explores and commits to different areas of life (James Marcia’s inspiration, n.d.). Diffusion, foreclosure, moratorium, and achievement are these statuses (Lally & Valentine-French, 2022). Though it might sound depressing to an inattentive reader, the phrase “speak / remembering / we were never meant to survive,” in fact, denotes a shift in the direction of achieving identity (Lorde, 1997, p. 256).

Accepting the fact that one is oppressed entails committing to a self-defined identity following an inquisitive and exploratory period. Furthermore, this point of Marcia’s model is remarkably similar to the first stage of Harro’s (2010a) Liberation Cycle. Speaking up in the face of fear and accepting one’s own identity is a sign of a state attained in which people let go of their cultural conditioning and embrace a truer version of themselves.

Other Research

The final reading of “A Litany for Survival” is that it describes the development of self-esteem, as can be seen through the sociometer theory of Mark Leary. According to Leary’s theory, one’s sense of self-worth serves as an internal sociometer that measures one’s acceptance and belonging in society (Pardede & Kovač, 2023). The poem’s recurring theme of fear is strongly related to the fear of being ignored, alone, and silenced. This fear is consistent with Leary’s theory that self-esteem is closely related to perceptions of social inclusion or exclusion. It speaks to the fundamental human need for social connection and acceptance, which are denied to marginalized individuals.

Lorde’s (1997) portrayal of people whose fear is “like a faint line in the center of our foreheads” (p. 255) highlights the long-lasting influence of cultural and societal norms on the growth of self-esteem. This is proven by research: individuals from marginalized communities frequently internalize prejudices and judgments from society, which lowers their sense of value (Park et al., 2023). Leary’s theory that self-esteem acts as a gauge of one’s perceived social value is supported by the fear that one will not be heard, acknowledged, or loved.

The poem also discusses the anxiety that comes with being alone and the fear that love might not come back. This loneliness fear emphasizes even more how crucial interpersonal connections are to the development and maintenance of self-esteem (see Figure 3). According to Leary’s sociometer theory, people keep a close eye on their social surroundings to determine how accepted they are (Pardede & Kovač, 2023).

The poem’s expression of fear highlights the importance of relationships in the growth and maintenance of self-esteem by implying a deep concern for social acceptance and connectedness (Lorde, 1997). Speaking up can be seen as a brave attempt to defy social norms and affirm one’s values, even in the face of fear and the inherent risk of not being heard. This is consistent with the notion that people who have higher self-esteem are more inclined to act assertively and refuse to submit to hierarchical structures.

Reflective Analysis

From the perspective of cognitive development, my early years were characterized by the assimilation of knowledge from my immediate environment, especially my family. In accordance with Piaget’s theory, when I was in the sensorimotor and preoperational stages of early childhood, I absorbed my parents’ values (Lally & Valentine-French, 2022). My worldview and the foundation for my socialization were shaped by the cognitive structures that developed during this time. From a behaviorist perspective, my family was also the main source of reinforcement and punishment, which shaped my attitudes (Lally & Valentine-French, 2022). In this sense, the family laid the groundwork for later stages of development.

It is clear to me now that my family’s early foundational influence on my thought processes has had a significant developmental impact on me. The story of my life expanded outside of my family into the worlds of friends, school, university, and work, where socialization continued to form my identity. This is the point at which my innate characteristics interacted with the outside stimuli provided by different social and educational environments, demonstrating the interaction between genetic and environmental influences.

As I think about my path to self-actualization, humanistic theories like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs become relevant (Lally & Valentine-French, 2022). My family’s and later friends’ and coworkers’ supportive environments helped me feel like I belonged, which created the environment for personal development. As one grows older, environmental influences continue to have an effect, particularly in the workplace. One of the most important turning points in my development is when I finally fit in with a particular social group at work. It gave me a platform to show off my skills and abilities.

The significance of Harro’s Cycle of Socialization becomes evident when considering the factors that influenced my early worldview. The family served as my first socialization source, imparting norms that I mostly followed but sometimes questioned in other social contexts, like school and then the workplace (Harro, 2010b). Eventually, I discovered in myself a desire to break free from the limitations of other people’s opinions, echoing the emancipatory process in the Cycle of Liberation (Harro, 2010a).

I struggle with the conflict between individuality and conformity, which is a conflict that is similar to Erikson’s psychosocial crisis of identity and role confusion (Lally & Valentine-French, 2022). Although Erikson links this conflict to adolescence, it took me many years to acknowledge that rather than just seeking approval from others, I desire an authentic understanding of who I am. The cyclical character of liberation emphasizes the continuous battle to overcome the limitations of social expectations (see Figure 4). I am continuously trying to overcome my fear of being judged; this is a battle that has its roots in both internal and external factors.

As I move between different social groups, it becomes clear how social and cultural influences interact and how each adds to the intricate fabric of my identity. The combination of these factors—familial, academic, and professional—testifies to the person I am today. When I think back on the changes in my own cycle, I see a move away from reliance on other people. In order to deviate from upholding oppressive values, I must actively confront social norms. In addition to releasing myself from outside restraints, my journey of liberation entails actively aiding in the destruction of oppressive systems that stifle me and others.

References

Defense mechanisms [PowerPoint slides]. (n.d.).

Eytan, T. (2020). Black Lives Matter Plaza, created by the Government of the District of Columbia, in the wake of the murder of George Floyd [Photograph]. Flickr. Web.

Harro, B. (2010a). The cycle of liberation. In Adams, M., et al. (Eds.), Readings in diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 52-59). Routledge.

Harro, B. (2010b). The cycle of socialization. In Adams, M., et al. (Eds.), Readings in diversity and social justice (2nd ed., pp. 45-51). Routledge.

James Marcia’s inspiration [PowerPoint slides]. (n.d.).

Kendall, K. (1980). Audre Lorde in Austin, Texas, 1980 [Photograph]. Flickr. Web.

Lally, M., & Valentine-French, S. (2022). Lifespan development: A psychological perspective. LibreTexts.

Lorde, A. (1997). The collected poems of Audre Lorde. W. W. Norton & Company.

Pakhrin, S. (2017). Women’s March – Washington DC 2017 [Photograph]. Flickr. Web.

Pardede, S., & Kovač, V. B. (2023). Distinguishing the need to belong and sense of belongingness: The relation between need to belong and personal appraisals under two different belongingness–conditions. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(2), 331–344. Web.

Park, L. E., Naidu, E., Lemay, E. P., Canning, E. A., Ward, D. E., Panlilio, Z., & Vessels, V. (2023). Social evaluative threat across individual, relational, and collective selves. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (pp. 139–222). Web.

Schultz, D. (n.d.). Audre Lord and May Ayim [Photograph]. Digitale Deutsche Frauenarchiv. Web.