Key Drivers of Innovation and Entrepreneurial Opportunities that Contribute to the success of Cirque du Soleil

Introduction

The present paper is devoted to an analysis of the key innovation drivers that can be regarded as contributors to the success of the Cirque du Soleil (CS). In particular, the paper uses Porter’s generic competitive strategies and five forces framework along with the resource-based view to discuss CS’s strategy. Also, the paper applies the 4 Ps of innovation as well as dichotomic “incremental-radical” and “system-component” classifications to describe the innovation used by CS. All these tools demonstrate the importance of innovation for the success of CS.

CS was established in 1984 in Canada (Quebec), and it is now one of the country’s “most important cultural exports” that tours all over the world and have a turnover of over $1 900 million (Gittleson 2013). CS is sometimes regarded as a revolutionary circus that changed the concept and the industry, creating a blue ocean for itself where no competition was to be found for some time (The Economist Team 2014, para. 4-5). As a result, it is an appropriate topic for the discussion of innovation and its contribution to success.

Key Drivers of Innovation

Identification

Performance, Theme, and Storytelling

CS reinvented the acts that should be used by a circus; in particular, CS does not employ animals and targets adults to a greater extent than children (The Economist Team 2014, para. 4). These features made CS an innovative player in the industry, even though other circuses started following it with time (The Economist Team 2014, para. 5-7). Today, CS presents its viewers with a mixture of street and circus entertainment and uses original concepts, lights, music, and costumes, (Moutinho 2016). Cirque du Soleil (n.d.) has multiple shows with specific themes, all of which are the products of a long creative process, which involves visionary guidance of the artistic director, brainstorming and discussion (where dissent and disagreements are and cultivated), concept development, quality control, and micro-management (Gittleson 2012, para. 1-5). Some of the company’s shows (beginning with Ka) contain a clear storyline (Moutinho 2016). Also, CS is known for its technology use, which helps in show development (Gittleson 2012, para. 6).

Creativity is the core of the company, and its founders and managers are all creative people, the majority of whom used to or proceed to perform in the circus (Low & Ang 2013). The creativity and uniqueness are used by the marketing of the company, which is aimed at setting apart and maintaining the brand despite imitators (Moutinho 2016).

Talented workforce and Related Issues

CS pays particular attention to its people (permanent shows employ over 5,000 people at a time), and it has special schools for some of them (The Economist Team 2014). Young employees are typically favoured over older ones (Gittleson 2012, para. 6), which might be considered discriminatory. Also, talents of CS tend to circulate within the industry and can be outsourced and attracted from multiple countries (Cirque du Soleil, n.d.; The Economist Team 2014), which increases the pool of talents available for the company. However, CS’s field of activities is dangerous: there have been several deaths among performers, including that of a co-founder’s son (Park & Allen 2016). According to the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, a show of CS that took place in Las Vegas in 2011 took the 79th place among the list of 52,000 most accident-prone workplaces (Berzon & Maremont 2015, para. 9). As a result, questions have been raised about CS’s treatment of its employees, especially those who receive traumas. Berzon and Maremont (2015) report that even in 2015, CS proceeds to treat its workers like regular ones, which presupposes limited compensation. On the other hand, CS reports that “some circuses” do not even classify their performers as employees, which is why they receive no coverage at all (Berzon & Maremont 2015, para. 10). Still, the issue is apparently problematic.

Analysis

Strategy Frameworks

When applied to CS (Barney & Hesterly 2012), Porter’s five forces framework suggests that at the time of the circus’ development, the industry had low attractiveness due to high bargaining power of buyers who were now interested in different, substitute forms of entertainment (Moutinho 2016). At the same time, giant and highly competitive circuses like Ringling Bros. were active (The Economist Team 2014). However, the bargaining power of suppliers (performers) and the threat of entry was lower because of the decline in the industry (Moutinho 2016).

The resource-based view (BRV) can shed some light on the way CS succeeded in entering this industry (Johnson et al. 2014): clearly, its resources were helpful in the process (Lin & Wu 2014). In particular, CS turned its unique (though imitable) image into a competitive advantage, employing, among other things, the growing concern for animal cruelty (Nijland, Aarts & Renes 2010). Apart from that, CS invested greatly in its valuable talents, therefore, employing both its key drivers (Moutinho 2016; The Economist Team 2014). Thus, if Porter’s generic strategies are applied to CS (Johnson et al. 2014), it appears that CS chose the path of differentiation through innovation.

Innovation Frameworks

Innovations are typically divided into incremental and radical ones (Norman & Verganti 2014; Ritala & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen 2012), and in the case of CS, the innovation was quite radical. The 4 Ps of innovation can demonstrate that this radical innovation can be found at least at three levels: of the product (the removal of animals), the paradigm (targeting adults instead of children), and the position (positioning oneself as a completely new, different type of circus) (Anderson 2013). Also, all these changes can be considered systemic (Mlecnik, 2013). Moreover, the processes of CS show development might also be considered innovative. For example, Gittleson (2012) insists that dissent is a relatively rare trait to cultivate in the show development process, which can be regarded as a component innovation (Joshi 2016). In general, the processes of CS are customised to its needs, which implies a certain level of component innovation.

The use of the mentioned strategy and innovation tools shows that they are interconnected and can be used together for a more detailed perspective on the events.

Conclusion

At the point of CS’s creation, the industry was experiencing a decline due to the development of more accessible forms of entertainment (radio, TV, later the Internet) and the growing concerns regarding animal treatment (Moutinho 2016; Zuolo 2016). Thus, the multi-level radical and incremental innovations of CS helped it to employ its resources and turn them into advantages that it needed to flourish. As a result of the impact of CS on the industry, one might consider CS in the context of the Blue Ocean theory (Agnihotri 2015).

Blue Ocean Strategy and the Success of Cirque du Soleil

Introduction

CS was founded in 1984, and throughout the 1990s and 2000s, it demonstrated rapid growth (Moutinho 2016). The global recession resulted in certain issues for CS, but its managers claim that the company does not experience a crisis (The Economist Team 2014). In other words, CS has been most successful, and some researchers attribute this success to the Blue Ocean Strategy (BO) (Moutinho 2016; The Economist Team, 2016).

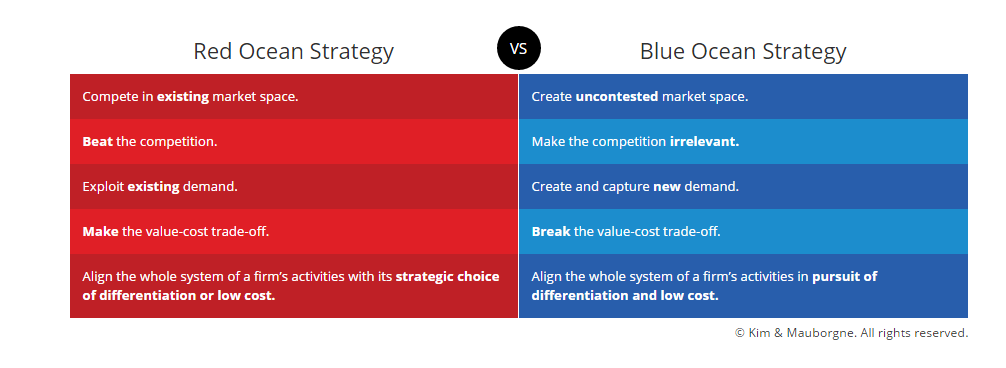

BO presupposes a data-based method of finding a differentiation strategy that employs a number of method-specific tools to create “uncontested market space” (Kim & Mauborgne 2016a, para. 3), which is termed as the “blue ocean” as opposed to the “red ocean.” In other words, a blue ocean is a market space that does not require struggling with the competitors, which is supposed to maximise the opportunities of the organisation that creates the ocean (Kim & Mauborgne 2013). Since red oceans imply limited opportunities, Kim and Mauborgne (n.d) strongly recommend searching for blue ones. The present paper investigates whether CS can be considered in terms of BO and suggests that the BO concept is only partially applicable to the case.

Cirque du Soleil’s Competition

Some researchers and specialists claim that CS used BO, which allowed it to flourish due to the lack of contestants in the ocean that CS has created (Moutinho 2016; The Economist Team, 2016). However, one of the founders of CS states that there are many “sharks” in that ocean nowadays. Older circuses have developed and innovated, and young ones might introduce something different, as well. For example, an important competitor of CS is the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey (RBBB) circus. One of the projects of Feld Entertainment (2016), RBBB has turned the phrase “The Greatest Show On Earth” into its officially registered trademark. It has been operating for 146 years, and its current style involves “combining long-standing circus tradition with leading-edge technology” (Feld Entertainment 2016, para. 1). It involves both humours- and danger-related acts, and new shows are always compiled for every new tour, which typically attracts over 10 million people.

Also, animals are an important part of the brand of the circus (Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Center for Elephant Conservation 2016). Apparently, the circus pays a lot of attention to the quality of life of its elephants, and it promises to give up the acts that involve these animals by 2018, even though it apparently considers them to be the symbol of its activities (Warshaw 2016). However, there have been issues with the treatment of other animals. For example, PETA reports that the circus uses psychological abuse to ensure the obedience of its tigers while also failing to ensure appropriate living conditions for the wild cats, for example, in terms of proper shading or conflict prevention structures (Warshaw 2016). Warshaw (2016) informs that Feld Entertainment chooses to discredit PETA’s report and insists that the tigers live in appropriate conditions. Still, it appears logical that animal use in circuses is bound to raise issues and can be regarded as a questionable practice, especially if it is a trademark. RBBB is an example of a major and mature competitor of CS.

Relatively young entrants are also worth noting (The Economist Team 2014). For example, Cirque Alfonse (2015) is nostalgia- and the family-oriented circus that was established in 2005 in Quebec. It employs acrobatic and dancing acts and pays particular attention to the folklore music employed during its shows, which have been shown across America, Europe, and Asia. Finally, the Economist Team (2016) reminds that other fields of entertainment should also be taken into account, especially as they develop and bring in some elements of circus into unconventional arts, for example, opera.

Tools and Frameworks

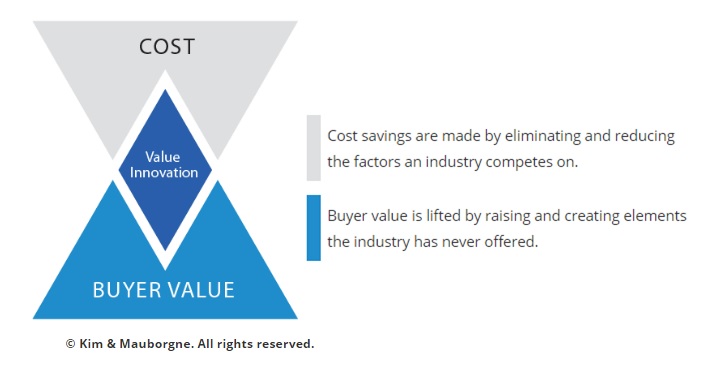

BO employs multiple tools to analyse and place strategies within the concepts of blue or red oceans. Figure 1 shows the Value Innovation Framework (VI) by Kim and Mauborgne (2016e), which can be used as a cornerstone of one’s BO to demonstrate the “simultaneous pursuit of differentiation and low cost, creating a leap in value for both buyers and the company” (para. 1).

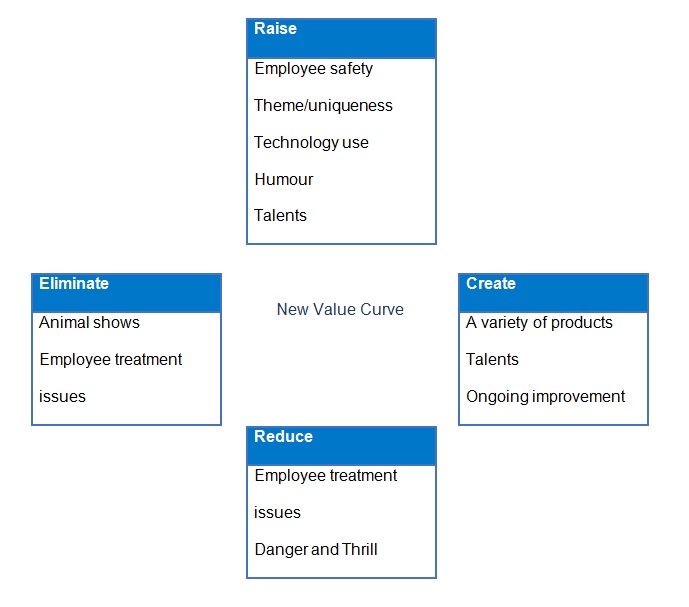

VI is closely connected to the Four Actions Framework (FA), as defined by Kim and Mauborgne (2016b) as the latter expands VI, which can be seen in Figure 2.

The information presented above and in the previous part of the task suggests that the BO of circus industry requires the elimination of the use of animals in acts as well as the elimination of danger for the employees (Moutinho 2016). Unfortunately, the latter may be difficult or even impossible (Park & Allen 2016), which is why it can be suggested that if the problem is not eliminated, it needs to be reduced. It would be expected that together with the safety issues, danger and thrills will be reduced. Finally, the issues in employee treatment also need to be eliminated or reduced (Berzon & Maremont 2015, para. 9). Concerning paths for improvement, they are multiple. Employee safety can be mentioned again; apart from that, the creativity of CS presupposes the development of new unique themes. Humour can be regarded as a safe alternative of danger and thrills, which implies that it can be raised to complement the reducing danger. Technology and talents require ongoing search and improvement. Apart from that, new talents can be created, and the ongoing improvements and new products can be regarded as a part of FA that is associated with the “create” action. Figure 2 summarises the application of FA to CS. Returning to VI, one can see that by eliminating and reducing the issues while raising and creating the advantages, CS can reach the Value Innovation diamond that is coloured deep blue in Figure 1.

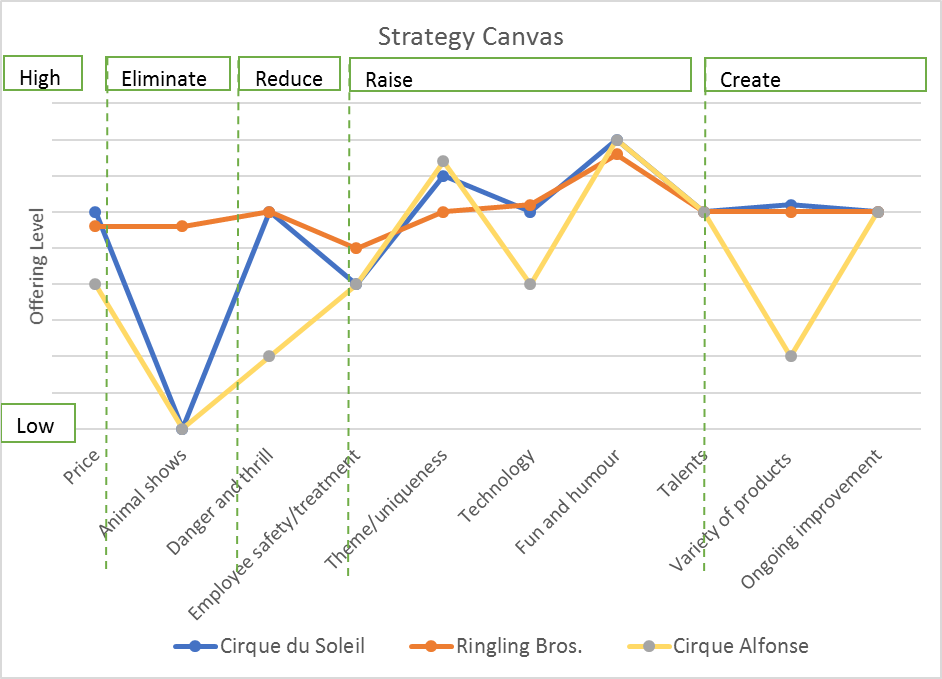

FA can also be united with the Strategy Canvas Tool (ST), which represents value curves for the case study and its competitors (Kim & Mauborgne 2016d). Indeed, the actions from FA can be embedded in ST, as Figure 3 demonstrates. Apart from that, it illustrates the differences between CS and its competitors in the mentioned activities. Employee safety is reduced to one activity in Figure 3 (the one that needs to be raised); also, the talents are placed between raising and creation since CS is known to both search for and create talents (The Economist Team 2014).

Figure 3 shows that CS has succeeded in eliminating animal shows, which distinguishes it from RBBB, but Cirque Alfonse (2016) has also managed to achieve this outcome. In their treatment of the workforce, technology, and talents, the three circuses are similar, even though Cirque Alfonse (2016) may be using less technology. Also, Cirque Alfonse (2016) is less reliant on danger and thrill, which is an achievement, in which is outperforms CS and RBBB, but this circus has very few products (only three shows for the time being), even though this aspect is likely to change in the future. Thus, ST allows summarising VI and FA, which enables one to consider CS from the point of view of the BO concept.

Figure 4 demonstrates the differences between red and blue oceans (ROBO) as defined by Kim and Mauborgne (2016c). The tools that have been used above can be employed to characterise CS’s strategy with the help of this figure.

The question of whether CS has managed to create an uncontested market space is unlikely to be answered positively. Nowadays, the growing competition from imitators, red ocean giants (like RBBB) and original newcomers (like Cirque Alfonse) make this suggestion impossible (The Economist Team 2014). As for the market niche that CS developed in the 1990s, it may be regarded as unique, but it can hardly be considered uncontested. Figure 3 demonstrates that at least some elements of CS’s strategy have been contested by RBBB since the beginning. Apart from that, while CS avoids RBBB’s issues with animals, RBBB does not appear as often in employee issues scandals.

Possibly, animal RBBB issues are more visible due to PETA activities, but the fact that a CS’s show features as one of the most dangerous workplaces implies that CS has a weakness and performs worse than RBBB in this respect (Berzon & Maremont 2015, para. 9). As a result, it is questionable that CS has ever existed in a perfectly uncontested environment, and the competition is unlikely to have ever been completely irrelevant for it (The Economist Team 2014). At the same time, the circus must have managed to capture a new demand (for an original circus that does not employ animals), and CS’s activities seem to be aimed at differentiation (Moutinho 2016). Still, no evidence was found during this research to the idea that CS specifically works to reduce costs, and the analysis of VI and FA suggests that it still needs to work to break the value-cost trade-off. To sum up, the application of ROBO to CS implies that its strategy is not a BO one.

Conclusion

The application of the tools and frameworks of BO demonstrates that they can be used in tandem to produce a comprehensive overview of a company’s strategy. They may complement or expand each other, which results in more detailed descriptions and a deeper understanding of a company’s ocean.

It is noteworthy that BO has been criticised for multiple aspects, including the difficulty of the theoretical elimination of competition and the inevitability of BO turning red (Burke, Stel & Thurik 2016; Wee 2016). It should be pointed out hat BO remains a highly influential and useful framework (Randall 2015), but it may be suggested that it should be complemented with other ones to achieve a better understanding of a market or strategy (Wee 2016). As for CS, the concept of BO is only partially applicable to it.

CS entered a declining industry and introduced a series of innovations that have contributed to the company’s success by differentiating it from the rest. However, it is questionable that the innovations allowed for the creation of a new, competition-free blue ocean. It is noteworthy that classic BO is considered to be opposed to the classic differentiation strategy in searching to break the cost-value trade-off (Randall 2015). In the end, it may be suggested that BO is only partially applicable to CS.

Reference List

Agnihotri, A 2015, “Extending boundaries of Blue Ocean Strategy”, Journal of Strategic Marketing, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 519-528.

Anderson, TD 2013. “The 4Ps of Innovation Culture: Conceptions of Creatively Engaging with Information”, Information Research: An International Electronic Journal, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 1-16.

Barney, JB & Hesterly, WS 2012, Strategic Management and Competitive Advantage: Concepts and Cases, 4th edn, Pearson Education Limited, London, United Kingdom.

Berzon, A & Maremont, M 2015, “The perils of workers’ comp for injured Cirque du Soleil performers”, The Wall Street Journal, Web.

Burke, A, Stel, A & Thurik, R 2016, “Testing the Validity of Blue Ocean Strategy versus Competitive Strategy: An Analysis of the Retail Industry”, International Review of Entrepreneurship, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 123-146.

Cirque Alfonse 2015, Web.

Cirque du Soleil n.d., Web.

Feld Entertainment 2016, About Feld Entertainment, Web.

Gittleson, K 2012, “The secret that inspires Cirque du Soleil’s culture of innovation: creative friction”, Forbes, Web.

Gittleson, K 2013, “How Cirque du Soleil became a billion dollar business”, BBC, Web.

Johnson, G, Whittington, R, Scholes, K, Angwin, D & Regner, P 2014 Exploring Strategy: Text and Cases, 10th edn, Pearson Education Limited, London, United Kingdom.

Joshi, A 2016, “OEM implementation of supplier-developed component innovations: the role of supplier actions”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, vol. 1, pp. 1-21.

Kim, W & Mauborgne, R 2013, Blue ocean strategy, Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Kim, W & Mauborgne, R 2016a, 8 key points of Blue Ocean Strategy, Web.

Kim, W & Mauborgne, R 2016b, Four Actions Framework, Web.

Kim, W & Mauborgne, R 2016c, Red Ocean vs. Blue Ocean strategy, Web.

Kim, W & Mauborgne, R 2016d, The strategy canvas, Web.

Kim, W & Mauborgne, R 2016e, Value Innovation, Web.

Kim, W & Mauborgne, R n.d., What makes blue ocean strategy imperative in today’s business climate, Web.

Lin, Y & Wu, L 2014, “Exploring the role of dynamic capabilities in firm performance under the resource-based view framework”, Journal of Business Research, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 407-413.

Low, KCP & Ang, SL 2013, “Blue Ocean Strategy and CSR”, in SO Idowu, N Capaldi, L Zu & A Gupta (eds), Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility , Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, pp. 179-188.

Mlecnik, E 2013, “Opportunities for supplier-led systemic innovation in highly energy-efficient housing”, Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 56, pp. 103-111.

Moutinho, L 2016, Worldwide casebook in marketing management, 1st ed, World Scientific Publishing, Singapore.

Nijland, H, Aarts, N & Renes, R 2010, “Frames and Ambivalence in Context: An Analysis of Hands-On Experts’ Perception of the Welfare of Animals in Traveling Circuses in The Netherlands”, Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 523-535.

Norman, D & Verganti, R 2014, “Incremental and Radical Innovation: Design Research vs. Technology and Meaning Change”, Design Issues, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 78-96.

Park, M & Allen, K 2016, “Cirque du Soleil co-founder’s son dies before show in SF”, CNN, Web.

Randall, R 2015, “W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne dispel blue ocean myths”, Strategy & Leadership, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 11-14.

Rantisi, N & Leslie, D 2014, “Circus in Action: Exploring the Role of a Translation Zone in the Cirque du Soleil’s Creative Practices”, Economic Geography, vol. 91, no. 2, pp. 147-164.

Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Center for Elephant Conservation 2016, Web.

Ritala, P & Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P 2012, “Incremental and Radical Innovation in Coopetition-The Role of Absorptive Capacity and Appropriability”, Journal of Product Innovation Management, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 154-169.

The Economist Team 2014, “Sunstroke”, The Economist, Web.

Warshaw, A 2016, “PETA: Ringling Bros. Circus abuses tigers”, The Daily Beast, Web.

Wee, C 2016, “Think tank – beyond the five forces model and Blue Ocean Strategy: an integrative perspective from Sun Zi Bingfa”, Global Business and Organizational Excellence, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 34-45.

Zuolo, F 2016, “Dignity and Animals. Does it Make Sense to Apply the Concept of Dignity to all Sentient Beings?”, Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 1117-1130.