Abstract

The current research dwells on the prevalence of delinquent behavior in teenagers residing in Columbia County, GA. The researcher effectively addressed the issues inherent in the concept of community policing and identified several programs that may help throughout the process of mitigating the occurrence rate of delinquencies. Moreover, the researcher brought up relevant statistics to assess the current and future levels of efficiency of these programs and reach several verdicts regarding the issue of juvenile delinquency in Columbia County. Overall, it was shown that the tendency in the area is positive, and neighborhood watch momentously impacts the occurrence of delinquencies committed by juvenile wrongdoers within the area of Columbia County, GA.

Impact of Community Policing on Juvenile Delinquency in Columbia County, Georgia

Introduction

The theory of community policing suggests the existence of an alliance between community members intended to reduce the fear of crime, bolster relationships, and promote a positive response to community difficulties. This theory requires law enforcement officers to deviate from vehicular patrolling to relationship building. It requires law enforcement officers to become more acquainted with community members than by visual familiarity. This acquaintance allows law enforcement officers an opportunity to familiarize themselves with the residents who live and work in this area. Through the community policing approach, law enforcement officers understand the needs of the community.

Community policing and policing the community may be similar in meaning; however, be executed differently (Bates & Swan, 2013) although both communities policing and policing the community shares the goal of maintaining good order, policing the community does not delve into cultivating relationships and mutual respect. The commonality or common good for these two approaches is a commitment to the general welfare of the communities being served (Milakovich, 2013). In cultivating relationships, adolescents in the community are sometimes more reluctant to engage in community policing.

The perception is that the police officers are visible only to make arrests, never to be of assistance. To the adolescent mind, law enforcement officers are the gateway to the criminal justice system (Hoffman, 2014). This rationale is understandable according to Laurence Steinburg, a Temple University Psychology Professor who stated, “an adolescent brain is like a car with a good accelerator but a weak brake; their brains have powerful impulses under poor control with a likelihood of resulting in a crash” (Ritter, n.d.).

According to the 2015 United States Census Bureau Report, Columbia County, Georgia, adolescents make up 1.41% of the total juvenile population for the entire state (Puzzanchera, Sladky, & Kang, 2016). Although 1.41% is a nominal percentage, it can be an enormous number of juveniles for law enforcement officers charged with establishing communal relationships.

There is a myriad of instances when police officers and youths encounter one another. In addition to enforcing the law, police officers engage in community service (“Body camera video shows police in Michigan, holding five innocent boys at gunpoint,” 2017).

This Community service may include providing information or assistance to community members in need. And in many communities, police officers network with residents to establish a police-community partnership. This partnership offers youth education initiatives and youth outreach. This partnership also addresses criminal activity with a focus on reducing the fear of social disorder through problem-solving strategies.

Typically, this involves a greater presence of foot and bicycle patrol officers and frequent meetings with community groups (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2017). Community policing encompasses a three-element strategy to enhance safety (Community oriented policing services, 2016):

- Forming partnerships because one party may not execute it efficiently (Wheeler, 2016).

- Organizational transformation whereby structures are re-arranged to suit community partnerships that enhance security (Wheeler, 2016).

- Incorporating problem-solving when a problem is identified, and suitable approaches are put in place to rectify issues (Wheeler, 2016).

Many law enforcement agencies acknowledge that community-oriented policing has played an integral role in addressing the sources of crime and encouraging a holistic problem-solving relationship that involves the community (Ray, 2014). Thus, community policing was implemented to develop healthy relationships between the residents of community and law enforcement officers. The main objective and aim of community policing are to reduce crimes being committed, thus reducing the number of arrests (Weisburd, 2015).

Successful community policing can be achieved through the identification and reporting of the identified crime. Siegel and Welsh (2013) acknowledge that police officers are not the sole guardians of law and order but are obligated to every stakeholder in the community to facilitate law and order. Embracing community policing is gaining momentum in contemporary society as residents of the community desire and are committed to participating in their community’s safety. From a philosophical perspective, community-policing strategies are rapidly evolving and are susceptible to changes because of the dynamic needs of a rapidly changing society (Sozer & Merlo, 2013). Community-oriented policing is also a significant approach to combating the war against crime through a mutually rewarding partnership.

This report highlights a perspective of the impact of community policing on juveniles not yet explored. This report also presents information on offense characteristics of juvenile arrests from 2011 through 2015 and explores the presence of any trends in juvenile arrests.

Statement of the Problem

Perception is vital to the success of any attempt at policing, and discernment is pertinent when executing community policing; therefore, community members must be able to trust and believe officers with whom they interact. Community members must be assured that despite historical behaviors and negative media coverage of previous encounters, minus intricate facts are not the norm.

The influence of juveniles’ perceptions and behaviors by biological and psychological factors are related to their developmental stage. They are much less insightful about the consequences or long-term effects of their behavior. Juveniles operate under the concept of “I want what I want, and I want it right now.” Therefore, the response they have when encountering law enforcement will be different from adults (Dacchille & Thurau, 2013).

Promoting community policing fosters a choice of exercising alternative deterrents such as rational persuasion and ingratiation for police officers. These tactics oppose the perception of increased negative interactions between the police and the youth. The first negative contact between the youth and the justice system increases the likelihood of subsequent reactions with the justice system as the youth gets older (Dacchille & Thurau, 2013). Thus, many law enforcement agencies approach the use of community policing as a way of deterring crime and changing the public attitude about law enforcement (Miller, Hess, & Orthmann, 2017).

Purpose of the Study

The goal of this study will analyze the impact of community policing on juvenile arrest rates in Columbia County, Georgia, by examining crime rates before and after community policing was implemented. The study will also determine the types of offenses committed by juveniles to determine whether community policing decreased juvenile crime rates. This study will identify the extent to which Columbia County Sheriff’s Department incorporates community policing in its overall policing strategy.

Significance of the Study

The perception of juvenile delinquency as an elevating problem is a society that may be erroneous (“Mind of adolescent,” n.d.). Subsequently, the media coverage of juvenile criminal behavior by the news, print, and social media infers the existence of official statistics to support the premise for this claim and therefore create a moral panic. This perception may be indicative of a failure to rely on statistical data for the exactitude of criminal behavior (Thompson & Bynum, 2016). Accurate statistical data is essential for three reasons:

- Parental Positions/Controls – Delinquency impacts everyone affiliated with the juvenile. Parents are responsible for the actions of their children.

- Police Officers/Administrators – Accuracy of data provides law enforcement with the information required for forecasting and personnel.

- Correctional Facilitators – Accuracy of data provides information pertinent to housing needs, personnel, and essentials such as meals and clothing.

Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework for this research is built upon determining how or if community policing is effective with juvenile delinquents. Also, if there is any significance in reducing juvenile crime rates through community policing. There has not been any specific study conducted or formally tested on the impact of community policing and juvenile crime rates in Columbia County, Georgia. However, there are statistical reports that allowed the researcher an opportunity to formulate a plan for examining findings. The purpose of the conceptual framework for this research is to permit the researcher to explore and explain the information available from previous researchers of this and related studies (Lai, 2013). Also, it is intended to explore information that includes logic based upon professional interviews and reports from federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies. These resources permitted the researcher the capability to format the study for simplicity and assessment of multiple viewpoints.

Literature Review

Introduction

The goal of this study will analyze the impact of community policing on juvenile arrest rates in Columbia County, Georgia, by examining crime rates before and after community policing was implemented. The study will also determine the types of offenses committed by juveniles to determine whether community policing decreased juvenile crime rates. This study will identify the extent to which Columbia County Sheriff’s Department incorporates community policing in its overall policing strategy.

Historical Considerations

Juvenile detention facilities did not exist in the United States until 1899. The youth-saving movement in the 19th century was successful in humanizing the criminal justice system by rescuing children from prisons and developing humanitarian judicial and penal institutions for juveniles (Krohn & Lane, 2015). In March of 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson called for a declaration on crime, which became the premise for community policing.

Since the emergence of modern urban societies, security and order has been the primary responsibility of community leadership. Urbanization is a feature of human civilization, but it has presented a challenge in maintaining law and order (Spring, 2016). In past standards, the community developed a mechanism for rewards and punishments. Today, the power of law enforcement is now concentrated within police departments and beheld by its officers.

Nevertheless, the late 20th and now the 21st centuries have challenged the militancy approach of traditional policing methods (Chriss, 2015; Kappeler & Gaines, 2012). The orthodox approach to policing was categorized as “of the people for the people.” This approach concluded that communities controlled police because police were merely citizens in uniforms.

Paradigm

Perception is a vital component of community policing. An officer’s initial reaction to an incident could be the impression a juvenile will harbor. The juvenile’s pre-conceived idea will either be confirmed or refuted by the interaction had with police officers. Police officers should enforce the written law by responding to legal characteristics of a situation; however, do so in a manner that is neither offensive nor physically abusive. Brogden and Ellison (2013) identified a Northern Ireland police department that utilized community policing as a solution and not a crime crisis. Agencies that strive to nurture community relations realize that without acceptance from community members, their efforts in reducing criminal activity would not be productive (Brogden & Preeti, 2013).

An example of community policing seemingly working well can be found in the North Little Rock Police Department with Officer Tommy Norman in North Little Rock, Arkansas. Officer Tommy Norman has been publicly recognized by a multitude of law enforcement agencies across this country as well as prominent public figures from the White House to state and local political leaders to entertainment elites for his work as a proponent of community policing (Brown, 2014).

Officer Norman can be seen and contacted through highly publicized and widely viewed social media platforms. This is where Officer Norman posts a few of his service-based acts with community members. Community members from elementary school-aged children to more senior members receive impromptu visits from Officer Norman at their homes and adult care facilities. He shares postings of his visits to local businesses within the community as well. His postings show him interacting with community members, both young and old, leaving the impression that there may be a family-like affiliation comparable to that of an uncle with a host of nephews and nieces.

Officer Norman’s actions seem to dispel negative impressions throughout his community. Officer Norman memorializes his interaction with community members that are chronically ill or afflicted with developmental disabilities. He also celebrates milestones for community members in the way of birthdays, graduations, anniversaries, and childbirths. He has established a morning routine of providing snacks for school-aged children at school bus stops (“Officer Tommy Norman,” 2017).

In contrast to Officer Norman, there was an unfortunate incident that transpired this past March between The Grand Rapids Police Department and juveniles of a community. On March 24, 2017, Officer Caleb Johnson, while patrolling a neighborhood, received a dispatched notification of a disturbance or fight at a recreation center within that community. Officer Caleb Johnson came upon a group of five male juveniles. The ages of these juveniles ranged from 12 to 14.

The recreation center was the location of the dispatched disturbance where the youths were playing basketball. The adolescents left the recreation center to walk home due to the disturbance. After answering that call, Officer Johnson observed the young men walking, stopped his patrol vehicle, and stepped outside of his vehicle. Officer Johnson then drew and aimed his service weapon at the juveniles. He instructed the young men to get on the ground at gunpoint. This incident is an example of how the absence of a community-oriented attitude, action, and focus can adversely affect the view of police for male juveniles (“Officer Caleb Johnson,” 2017).

The distinction between community policing and a traditional approach to policing is community policing focuses on a partnership between law enforcement and community. Moreover, community policing serves as a framework for problem-solving partnerships. Police officers engage community members through volunteering and providing education and services. The community policing approach aims at transforming negative perceptions and attitudes towards law enforcement and crime to positive and engagement (“Community Policing,” 2016).

Relationship to Other Studies

Albeit some policing is negative, many law enforcement officers strive to prevent crime before it can be committed (Lafrance & Day, 2013). Thus, community policing encourages law enforcement officers to act on concerns within the community before any crime being committed to thwarting off any intent to violate the law. Every member of the community has an integral role to play in community policing, which is pertinent to this strategic process, as they can report suspicious activities in their neighborhood to the police officers. According to the District of Columbia Lawyers for Youth (2014) reported, crime rates in the Metropolitan District of Columbia (MPD) have significantly reduced in the last ten years, and juvenile arrests decreased by 27% since 2009.

The DeMeester and LaMagdeleine (2015) report showed community policing within some agencies failed due to officers responding after crimes were committed as opposed to aiming at preventing crime from occurring. The report also mentioned financial constraints that budget allocations were below the actual amount required (Demeester, & LaMagdeleine, 2015).

Hypothesis of the Study

This study is based on the hypothesis that community policing is a vital instrument for crime deterrent, acting as a collaborative effort between police officers and community members that ultimately impacts the behavior of minors (Henry & Mackenzie, 2012). Secondly, Community policing prevents crime and fosters better relations between law enforcement agencies and the community. It is in this way that it is superior to other models of policing. Finally, there was a significant relationship between the reduction in crime and the successful implementation of the community-policing program.

Theoretical Framework

The Community Policing Consortium which consists of representatives from the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), the National Sheriff’s Association, the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF), and the Police Foundation, was commissioned to derive a community policing framework to share with other law enforcement agencies. The framework for community policing was intended to serve as a guide for procedures. A guide for procedures that provided law enforcement, community members, and lawmakers knowledge of how effective the impact of community policing was on crime rate, crime intensity, and threats to public safety (Understanding Community Policing, 1994, p. 1).

A community policing framework was developed to establish a best practice model that could be shared with other law enforcement agencies, created as a learning experience for law enforcement officers. It was designed to allow law enforcement officers, community members, and lawmakers the opportunity to review and share practices that worked well (Bar-Tal, Graumann, & Kruglansky, 2013). With the acknowledgment of which practice worked well, law enforcement agencies, community members, and lawmakers were then able to build upon those best practices with additional practices that were also found to work well.

Methodology

Research Purpose

This research aimed to evaluate the arrest rates of juveniles in areas of Columbia County, Georgia, where community policing was deployed as a primary patrol method. The research compared and contrasted crime statistics related to juveniles in the county from 2011 through 2015, determined the types of crimes juveniles committed during the specified period and evaluated whether crime decreased or increased during 2011 through 2015.

Research Design

In determining the impact of community policing on juvenile arrests, this convenience study employed mixed-method research, consisting of qualitative and quantitative measures. The study began with a meta-analysis of existing crime statistic data collected by law enforcement for both county and state agencies. Interviews were also conducted with Columbia County Sheriff’s Department’s Community Services official, The State of Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice Operations Manager, The State of South Carolina Department of Juvenile Justice Probation and Parole officer, and a Columbia, South Carolina Police Department Investigator. The study addressed these primary purposes:

- Types of crimes were committed by juveniles.

- The impact of community policing on juvenile arrest rates between 2011-2015 and correlation with community policing since implementation.

- Increase or decrease in specific crimes during 2011-2015.

Population and Sample

The research focused on Columbia County, Georgia, which, according to 2015 Census Bureau statistics, has a population of 35,012 juveniles up to 16 years of age. According to the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program from Georgia Crime Information Center of the Georgia Bureau of Investigations (GBI), the crime rate percentage in Columbia County, Georgia, was 18.7% (6,554 crimes). Of those 6,554 crimes, 1,089 are classified as violent, totaling 16.6%, and 5,465 property crimes totaling 83.4% are classified as property crimes.

The researcher collected many forms of statistical data from law enforcement agencies and publicly accessible websites of both county and state levels. When data was collected, descriptive and inferential statistics provided a different insight into the nature of data gathered to include (but not limited to): the total number of reported crimes, specific types of crimes committed, the profile of gender and race of juveniles committing crimes were analyzed. Interviews were conducted for verification of findings based on meta-analysis review.

Key Resources

The research used statistical data to establish a base for discussing the impact of community policing in Columbia County, Georgia. Two of the key resources in revealing statistics for this study were summary reports from the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program if Georgia’s Crime Information Center and The State of Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice.

Definitions

According to Ray (2014), community policing is the strategy that law enforcement units employ to curb and reduce crime rates. It is also a significant strategy that the law enforcement units incorporate to establish a meaningful rapport with members of the community. The Bureau of Justice Statistics (2017) categorizes community policing as a philosophy that promotes organizational strategies, which support the systematic use of partnerships and problem-solving techniques between the police and the community.

The Columbia County Sheriff’s Department Community Services Division under the leadership of Captain Clay Smith is responsible for community policing, public education on crime prevention, and various volunteer service programs such as Neighborhood Watch, Citizens Law Enforcement Academy, and Explorer Post #63 (“Columbia County Sheriff Department,” n.d.).

The definition of juvenile delinquents presented by Peck (2015) claims that these particular individuals are only minors that are aged 21 or under. The evidence that was collected throughout the research process from the crime report composed by Georgia’s Department of Juvenile Justice and Georgia Bureau of Investigation showed that delinquent behavior is commonly manifested by groups of individuals that engage themselves in criminal activities related to violence and property-related wrongdoings (Roth, 2013).

The evidence also suggests that the number of juveniles that engage in criminal activities does not exceed the critical limit. The issue is, juveniles are mostly related to the criminal groups that are also known as gangs. The characteristic feature of juvenile individuals, according to the crime reports, is their susceptibility to delinquent behavior. Mostly, the problems transpire when these individuals are not observed properly or become too influenced by their peers (peer pressure is also one of the contributing factors). The most prevalent crimes among juveniles are burglaries, rapes, and thefts.

The Department of Juvenile Justice Department defines intake as the process for determining whether the interests of the public or the juvenile require the filing of a petition with the juvenile court. Generally, a Juvenile Probation Parole Specialist receives, reviews, and processes complaints recommend detention or release where necessary, and provides services for juveniles and their families, including diversion and referral to other community agencies.

According to the Department of Juvenile Justice, commitment happens during the juvenile court disposition process. The court disposition process places youth in the custody of the DJJ for supervision, treatment, and rehabilitation (Eagly, 2016). Under the operation of law, the commitment order is valid for two years. DJJ makes the placement determination of whether the youth should be placed in the YDC or an alternate placement. Most often, youth is committed when probation and/or other services available to the court have failed to prevent youth from returning to the court on either a new offense(s) or violation of probation.

Summary of the Crime Reports in Columbia County

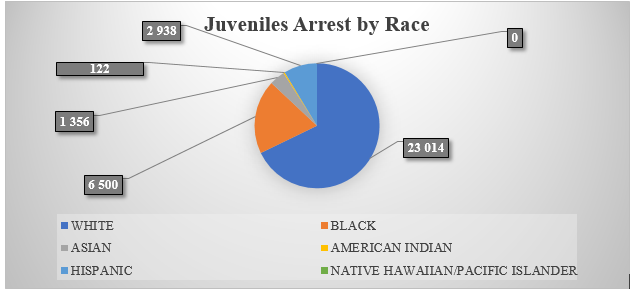

According to Keenan (2015), arrest rates among both male and female juveniles were high in Columbia County, Georgia, as they were engaged in both violent and non-violent criminal activity (murder, aggravated assault, vehicle theft, arson, and petty theft). Juveniles of all racial, ethnic make-up were represented in the statistical data collected (Deemaster, Magdeline, Norton, Austine, & Nadeau, 2015).

Juvenile crime statistics that were obtained helped the researcher to draw a series of conclusions regarding the juvenile crime statistics before the policy was implemented. First of all, it is important to mention that the overall crime situation in the area can be described as relatively safe because it is 59% safer than other neighborhoods in the area (“Community services division,” n.d.).

The crime rate in Columbia County is one of the lowest in Georgia as the county takes one of the top places on the chart of the safest communities in the State of Georgia. The occurrence of juvenile crime in Columbia County can be defined as 1:110 (where one of one hundred and ten individuals become the victims of juvenile delinquencies) (“Community services division,” n.d.).

It is also important to mention that the juvenile crime rate seriously impacts the well-being of the residents of Columbia County despite being outstandingly lower than in any of the other neighboring Georgia counties. Accordingly, there are juvenile crimes that are closely related to property crimes and some violent delinquencies. Another important finding regarding the overall rate of juvenile crime in Columbia County is that truancy, burglary, and DUI are other types of crimes that are the most prevalent among the teenagers that reside in Columbia County, GA (“Community services division,” n.d.).

The research on the subject also showed that Columbia County adolescents were susceptible to committing armed robberies and assaults. Even though the overall crime climate can be described as normal, there are numerous cases of juvenile delinquencies that can critically impact the residents of Columbia County (“Community services division,” n.d.). To conclude, the visitors and the residents of Columbia County both have a relatively high chance of becoming the victims of juvenile crime. Among the teenagers, burglaries and other property crimes were found to be the most popular.

Delimitations

Throughout the study, preconceived ideas and assertions were difficult to abstain from due to prior law enforcement experience and military affiliation of the researcher. Impartiality was most difficult due to an inherent awareness of the researcher’s bias as a parent. The study was confined to a region where the researcher resides for accessibility purposes, therefore, making this a convenience study.

Access to juvenile arrests records for specifics of criminal activity was unavailable to the researcher due to sensitivity and governing laws. Juveniles in county or state custody retain constitutional considerations and rights; therefore, interviews were also not permitted. The 2015 Juvenile Justice Decision Point Report was not available; therefore, the 2014 calculations were utilized. The next chapter will contain the findings of this research.

Results

Introduction

Within the framework of this study, the impact of community policing is reviewed and carefully assessed. The researcher takes into account the arrest rates of juveniles in Columbia County and examines the effects of community policing both before and after the implementation of the latter. Overall, the study will determine whether the employment of community policing is beneficial to the local community and observe the crime rate among juvenile individuals in Columbia County. This particular research project will also make conclusions regarding the extent to which the policies are incorporated into practice by the Columbia County Sheriff’s Department.

Columbia County, Georgia, is an example of an area in which community policing is the primary method of patrol utilized by the sheriff’s department (“DC lawyers for youth,” 2015). The combination of effort on behalf of community members and law enforcement officers’ produce gains for the entire county. Consequently, the idea of neighborhood policing plays an integral role in identifying high and low-level crimes (Roth, 2013). This is achieved by informing police officers of criminal activities either by calling a toll-free number or an established local non-emergency number. This action can be executed either anonymously or not. Second, there are specific patrol units for different sectors of the county that have the same objectives for enforcing the law and building a rapport with community members (Rogers, 2016).

Columbia County considers its patrol division to be the cornerstone of community policing. They must provide 24-hour law enforcement service to all residents (Smith, n.d.). Their patrolling body consists of 72 certified officers who work in shifts to maintain an around-the-clock law enforcement presence. The division also receives significant support from the federal and local governments. This support consists of much-needed equipment used during patrols and support of established programs that continuously promote effective community relations.

Discussion of Findings

Lieutenant Patricia Champion and Sergeant Daniel Massey of the Columbia County Sheriff’s Department Community Services Division indicated that for over 20 years, the Columbia County Sheriff’s Department engaged in community-oriented policing and patrolling (“Community services division,” n.d.). In fact, during the early 1990’s the sheriff’s department implemented the Neighborhood Watch partnership with community members geared toward decreasing crime. The goal was to reduce opportunities for crime by allowing community members to act as eyes and ears for the Columbia County’s Sheriff’s Department.

The department has developed a community/law enforcement partnership through shared information, observation, and reporting of suspicious activity, persons, or vehicles. These efforts enhanced the quality of life for all residents in Columbia County, Georgia (“Community policing,” n.d.).

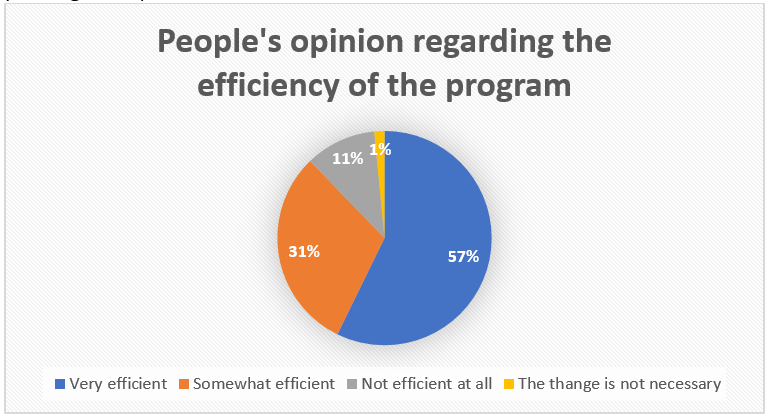

If we address the opinions of the residents of Columbia County (see Figure 3), we will see that the majority of respondents appreciate the implementation of the new neighborhood watch partnership. Research showed that very few people did not believe that neighborhood watch has a momentous influence on the prevalence of juvenile crimes in Columbia County. It is reasonable to conclude that neighboring counties may also make the best use of a similar tactic when approaching the issue of juvenile delinquency.

The Columbia County Sheriff’s Department maintains the Gangs Resistance Education and Training (G.R.E.A.T.) Program (see Figure 4). The program was initiated in 2002, which took the place of the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D. A. R. E.) Program. G.R.E.A.T. program fixated on 6th-grade students and engages the students in a 13-week life-skills competency curriculum designed to provide students with the skills they require to evade gang influence and youth brutality. G.R.E.A.T.’s prevention of violence instructional curriculum assists student’s development, beliefs, and practice behaviors that will avail them escape from destructive practices. G.R.E.A.T. originated through a cumulated aim of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF), and the Phoenix Police Department, Phoenix, Arizona.

The effort was congressionally fortified as a component of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms Project Outreach (Massey, n.d.). For Columbia County, Georgia, in 2015, there was a total of 2,186 6th graders available to engage and impact with this program. Utilizing the 2015 UCR statistic, 6,554 juveniles ranging in age from 0 to 16 years old had committed crimes, which totaled 33.34% of the juvenile population for the entire state (“MPDC annual reports,” n.d.).

The statistic shows that the number of prevented instances of delinquent behavior grows annually. Hence, it is reasonable to assume that the local government and law enforcement agency would like to concentrate on developing this program and enticing the county’s residents to participate in the neighborhood watch program discussed above. The impact is proved to be positive, so it is critical to maintain the existing level of performance and teach teenagers not to engage in delinquent behaviors.

Columbia County Sheriff’s Department Community Service Division also has the Sheriff Telling Our Parents and Promoting Educated Drivers (S.T.O.P.P.E.D.) Program. S.T.O.P.P.E.D. is a notification system for parents of drivers within the household under the age of 21 who have been stopped by law enforcement, whether a citation was issued or not (see Figure 5).

The program is voluntary and provides parents an additional mode of monitoring for their young drivers. The majority of Columbia County residents found this initiative rather helpful and claimed that it is pivotal to develop this program further and implement it on a state-wide level. The proposal sounds relatively reasonable, especially if one pays attention to the fact that a momentous percentage of Columbia County residents have never heard of this initiative. This implicitly hints at the fact that this particular initiative has great potential in terms of minimizing the occurrence of delinquent behaviors in teenagers residing in Columbia County and its vicinities. The number of individuals who perceive the effects of the S.T.O.P.P.E.D. program as negative is low (as it was expected by the researcher).

In speaking with Ms. Marshelle Pope, Operations Support Manager for the State of Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ), information regarding juveniles that are on probation for violations is the focus for her division. They also supervise juveniles that are both in detention facilities and are committed. Committed juveniles can consist of At-Home, Non-Secure Residential Treatment, Regional Youth Detention Center (RYDC) Awaiting Placement, and Youth Detention Center (YDC). They have critical juveniles between the ages of 12 and above; however, each case is handled individually (Pope, 2017).

The Department of Juvenile Justice website lists the mission statement. It states, “to protect and serve the citizens of Georgia by holding young offenders accountable for their actions through the delivery of services and sanctions in appropriate settings and by supporting youth in their communities to become productive and law-abiding citizens.” (Department of Juvenile Justice,” n.d., 2017).

A juvenile is received from a county agency after being arrested for a crime. The DJJ will become involved in the entire process of the juvenile’s case, from Intake to Commitment. Intake involves the juvenile court system and the court service system of the Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ). In the course of the intake process, a Juvenile Probation Parole Specialist may:

- informally adjust the case,

- file a petition with the juvenile court for adjudicatory proceedings,

- divert the case to services outside the court or;

- recommend that the case is dismissed.

From the findings of the research project, we can tell that the overall level of crime has decreased significantly. From the chart (see Figure 6), it can be noticed right away that the tendency of an increased number of juvenile delinquencies throughout the summer is still in place. Still, the overall percentage of committed crimes has decreased if compared with the number of crimes committed in 2016.

We can also witness an increase in the number of crimes committed by juveniles during the Christmas and New Year’s Eve holidays. Nonetheless, the overall verdict that was reached after the analysis of the findings is that the crime rate has decreased. This hints at the fact that the implementation of the policy was successful, and it is beneficial for both the community and the juvenile criminals. Also, based on the findings, one can conclude that the policy allowed to equalize the overall crime occurrence as now there is no such thing as a steep criminal tendency among juveniles, and the crime rate curve is equalized.

The policy was found to be effective, and this discovery was in line with the thesis of the study. The statistics validated the research question and were proven to be accurate within the framework of the current study. The overall criminal climate in Columbia County can be described as relatively peaceful, and the number of juvenile crimes has reduced because of the implementation of the policy. The researcher believes that further modification of the policy will help to adjust it to the criminal environment in real-time and reduce juvenile crime rates even more.

Conclusion, Policy Recommendation, and Further Research

The goal of this study will analyze the impact of community policing on juvenile arrest rates in Columbia County, Georgia, by examining crime rates before and after community policing was implemented. The study will also determine the types of offenses committed by juveniles to determine whether community policing decreased juvenile crime rates. This study will identify the extent to which Columbia County Sheriff’s Department incorporates community policing in its overall policing strategy.

Community policing is a critical strategy in Columbia as it enhances security. The statistical data indicate community policing has shown improvement; however, in 2011 and 2014, violent and property crime rates by juveniles increased. A decline in violent and property crime rates are reported for 2015, which substantiates the hypothesis that community policing was effective in this community.

The historical data regarding juvenile delinquency shows that there is a constant decline in the number of crimes committed. Even though the numbers dropped to the lowest level in the last three decades, it is important to remember that juveniles are mostly incarcerated for violent crimes (that should be eradicated from society completely). The periodic reports on the issue show that there is a steady trend in the number of crimes.

Currently, the number of homicides that are committed by juvenile offenders has reached its lowest level in the last two decades. One of the factors that may have majorly contributed to the decline is increased governmental attention to child safety and welfare. Compared to the previous decades, the cost of detention has increased. On a bigger scale, this has a significant impact on the criminal justice system and forces the government to search for other possibilities to punish juvenile offenders. The historical data shows that the efforts that were made to reduce the incarceration costs and the occurrence of violent crimes also impacted the occurrence rate of some lower-level crimes. Despite the positive outcomes of the majority of governmental programs, the arrest rates continue to grow gradually not only in the juvenile group but for adults as well.

The percentage of arrests increased from 26% to 38%, but it is rather interesting that this statistic does not reflect the occurrence of crimes. Regardless, it is safe to say that the most pivotal influence on the arrest rates is caused by the policy and constant adjustments that are made. The picture of juvenile crime is rather complex, but the overall rates continue to decline.

One recommendation derived from this research is that governing officials should remain focused on community policing as a best practice nation-wide. When properly funded and supported, community-focused policing is efficient. Another recommendation is to have law enforcement agencies to initiate and sustain an annual acknowledgment program. This acknowledgment program will entice police officers and community members to remain committed to the partnership. One more recommendation is positive teenage development. There is a specific model that is aimed at satisfying the needs of juveniles who are susceptible to committing crimes.

To be able to address the issue, the government will have to address some of the spheres of life that can influence juveniles. These include education, health, community, creativity, and work. To continue to improve the community policy, teenagers have to be taught to learn, and attachment should also be in place. If these requirements are followed, community policing is expected to have an even more serious impact on juvenile offenders.

Yet another option that is available to the policy-makers in the development of family-based interventions. This supposition is based on the fact that the parents’ style of parenting is directly connected to the likelihood of illicit and antisocial comportment of their children in the future. The new community policy should take it into account to provide help to those parents who cannot cope with their kids. Therefore, the recommendation revolves around the idea that it is critical to observe the child’s wrongful behavior and their school truancy. The program may also make the best use of teacher reports when it is needed to evaluate the possible crime rate tendencies.

Further research should focus on investigating more strategies to supplement community policing. It is evident from the research that community policing alone cannot be used to achieve zero juvenile crime or arrest rates in society. Other methods should be put in place to find alternative solutions to eliminate juvenile crimes.

This study is based on the hypothesis that community policing is a vital instrument for crime deterrent, acting as a collaborative effort between police officers and community members that ultimately impacts the behavior of minors. Secondly, Community policing prevents crime and fosters better relations between law enforcement agencies and the community. It is in this way that it is superior to other models of policing.

Finally, there was a significant relationship between the reduction in crime and the successful implementation of the community-policing program. The community met the program with enthusiasm, and this majorly contributed to the overall success of the policing. In terms of before-after comparison, the policy can be seen as effective and relevant within Columbia County. The occurrence of the most prevalent crimes among juveniles dropped suggestively and positively impacted the outlooks of Columbia County residents on the eminence of the proposed community policing program. Overall, the implementation of the program proved to be effective and positively affected the criminal environment in the area.

References

Bar-Tal, D., Graumann, C., & Kruglansky, A. (2013). Stereotyping and prejudice: Changing conceptions. New York, NY: Springer.

Bates, K. A., & Swan, R. S. (2013). Juvenile delinquency in a diverse society. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Body camera video shows police in Michigan holding 5 innocent boys at gunpoint. (2017). Web.

Brogden, M., & Ellison, G. (2013). Community policing: International concepts and practice. Cullompton, UK: Willan.

Brogden, M. & Preeti, N. (2013). Community policing. New York: Routledge.

Brown, J. (2014). The future of policing. Abingdon: Routledge.

Chriss, J. J. (2015). Beyond community policing: From early American beginnings to the 21st Century. New York, NY: Routledge.

Community oriented policing services. (2016). Community policing defined. Web.

Community policing. (n.d.). Web.

Community services division. (n.d.). Web.

Dacchille, C., & Thurau, L. (2013). Improving police: Youth interactions. Web.

DC lawyers for youth. (2015). Trends in the District of Columbia 1998-2014. Youth Arrest and Court Involvement. Web.

Deemaster, D. S., Magdeline, D. L., Norton, C., Austine, L., & Nadeau, S. (2015). The rebirth of community policing: A case study of success. Web.

Eagly, I. V. (2016). Immigrant protective policies in criminal justice. Texas Law Review, 95(2), 245-323. Web.

Henry, A., & Mackenzie, S. (2012). Brokering communities of practice: A model of knowledge exchange and academic-practitioner collaboration developed in the context of community policing. Police Practice and Research, 13(4), 315-328. Web.

Hoffman, J., (2014). In interrogations, teenagers are too young to know better. The New York Times. Web.

Kappeler V.E. & Gaines, L.K. (2012). Community Policing: A Contemporary Perspective. New York, NY: Routledge.

Keenan, V. M. (2015). 2015 Summary report Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program.

Krohn, M. D., & Lane, J. (2015). The handbook of juvenile delinquency and juvenile justice. Chichester, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

Lafrance, C., & Day, J. (2013). The role of experience in prioritizing adherence to SOPs in police agencies. Public Organization Review, 13(1), 37-48. Web.

Lai, Y. (2013). Policing diversity: Determinants of white, black, and hispanic attitudes toward police. El Paso, TX: LFB Scholarly Publishing LLC.

Massey, D. (n.d.). Columbia county, GA: Community services division. Web.

Milakovich, M.E. (2013). Public administration in America. (11th ed.). Miami, FL: University of Miami.

Mind of adolescent. (n.d.). Web.

MPDC annual reports. (n.d.). Web.

Peck, J. H. (2015). Minority perceptions of the police: A state-of-the-art review. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 38(1), 173-203. Web.

Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., & Kang, W. (2016). Office of juvenile justice census. Web.

Ray, J. M. (2014). Rethinking community policing. El Paso, TX: LFB Scholarly Publishing.

Ritter, M. (n.d.). Experts link teen brains’ immaturity, juvenile crime. Web.

Rogers, K. (2016). The new officer friendly, armed with Instagram, tweets, and emojis. New York Times. Web.

Roth, J. J. (2013). Commentary: Place-based delinquency prevention: Issues and recommendations. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 3(1), 110-121. Web.

Siegel, L. J., & Welsh, B. C. (2013). Juvenile delinquency: The core (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage.

Smith, C. (n.d.). Columbia county, GA: Community services division. Web.

Sozer, M. A., & Merlo, A. V. (2013). The impact of community policing on crime rates: Does the effect of community policing differ in large and small law enforcement agencies? Police Practice & Research, 14(6), 506-521. Web.

Spring, J. H. (2016). Deculturalization and the struggle for equality: A brief history of the education of dominated cultures in the united states. New York, NY: Routledge.

Weisburd, K. (2015). Monitoring youth: The collision of rights and rehabilitation. Iowa Law Review, 101(1), 297-341.

Wheeler, H. (2016). Perspectives on policing: Selected papers on policy, performance and crime prevention. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers.