The Pyramid of Menkaure and the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut are two significant buildings from ancient Egyptian heritage. The Pyramid of Menkaure is located on the Giza Plateau and was built during the Old Kingdom period around 2500 BC. Ordered by the Egyptian pharaoh Menkaure, the pyramid was assumed to become his tomb. The Temple of Hatshepsut was erected in the early fifteenth century BC during the New Kingdom period by order and during the reign of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut. This temple is located at Deir el-Bahri, next to the Valley of the Kings. The temple was not supposed to be a tomb but was intended to be a place to worship the gods and commemorate the ruler. Both buildings are masterpieces of the architecture of ancient Egypt; however, they differ in appearance, shape, structure and purpose.

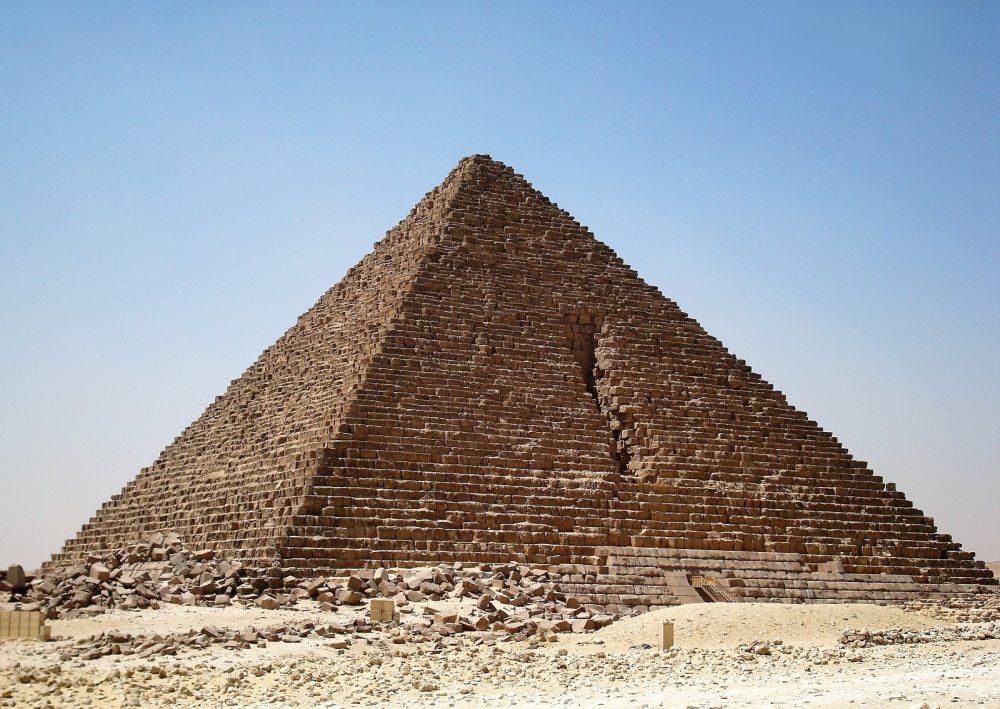

The Pyramid of Menkaure, called “Menkaure is Divine”, is the smallest of the three main pyramids of the pharaohs at Giza. It marked the end of the period of construction of giant pyramids as burial places for the pharaohs. Researchers believe that this pyramid and the burial complex were not completed due to the king’s untimely death, and some parts were completed later. The pyramid was the main structure of the burial complex, which also included three smaller pyramids, the mortuary, and the valley temples. During excavations on the burial complex’s territory, many statues were found representing pharaohs in the company of the queen or various deities.

The pyramid’s height reached 65 meters; it was built from large limestone blocks quarried in Giza to avoid long-term transportation. Some of the blocks weigh more than 200 tons and are larger than the blocks in the Khufu and Khafru pyramids. The interior of this building was similar to other pyramids but had different cladding. The surface was made of diverse materials: the first sixteen rows are covered with pink granite of Aswan, and the rest with white limestone. The entire pyramid was probably supposed to be covered with pink granite, but the builders finished the cladding with limestone after the pharaoh’s death. The entrance to the pyramid is at the height of four meters from its northern side. Inside, a downward path leads to the antechamber, the walls of which imitate false doors, a typical motive for those times. Among the internal structures of the pyramid, there is also a burial chamber lined with granite, in which the pharaoh’s sarcophagus stood, and another chamber containing six niches, in which canopic jars and the ruler’s property were kept.

The tombs were an essential structure for the ancient Egyptians, as they represented the only way to the afterworld and “guaranteed” a worthy afterlife for the deceased. The pyramid and its filling reflected the high status of the king; the additional chambers contained everything that the deceased might need in the afterlife. The pyramids themselves testified to the greatness of the ruler, in a sense, deifying him. The paintings and ornaments of the interior were not decorations, but instructions for the deceased, which helped his soul move to the world of the dead.

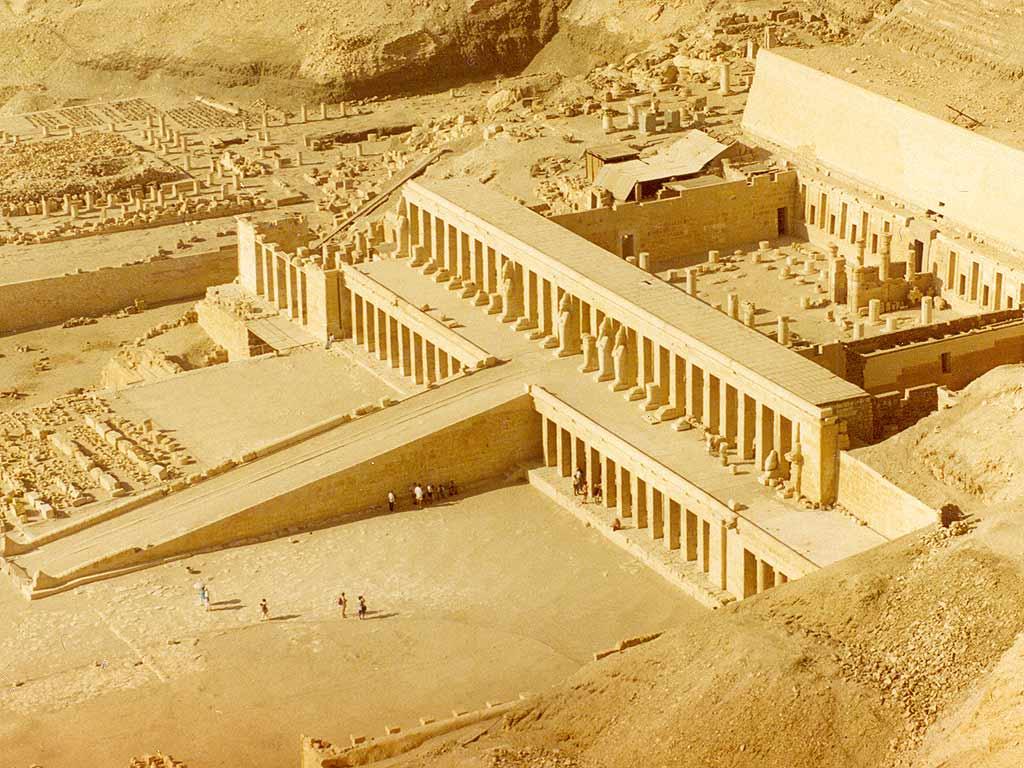

The Temple of Hatshepsut is a mortuary temple dedicated to pharaoh Hatshepsut and the god Amun-Re. This structure is cut right into the rock and has three terraces located at different levels and connected by ramps. The reliefs of each of the terraces told about some events or were dedicated to existing people as well as deities. A long valley of the queen’s sandstone sphinxes led to the lower terrace, which was decorated with falcons. At the end of this terrace was an entrance with 22 columns and a ramp separating them. Previously, there were giant statues of queen Hatshepsut and lion figures. The second tier of the temple, in many ways, resembles the lower terrace. Along the edges of the second terrace are the sanctuaries of gods Anubis and Hathor. Both sanctuaries consist of 12-column hypostyle halls and interior chambers that go deep into the rock.

The uppermost terrace was intended for rituals. Previously, the entrance was decorated with a portico with giant and majestic statues of the pharaoh. A complex system of rocky underground halls was located directly behind the entrance. Here were located the statues of Hatshepsut, which previously numbered about 200, of which 140 were sphinxes. On the sides of the central courtyard of the third terrace were the sanctuaries of Ra and Hatshepsut’s parents, Thutmose I and Ahmose. In the center of this complex is the sanctuary of Amun-Re, which was the most important and most intimate part of the entire Deir el-Bahri temple. The building was crowned with a giant portrait of Hatshepsut herself in the form of a sphinx.

The tomb of Hatshepsut was not located on the temple’s territory. The temple complex included the causeway, the mortuary and the valley temples, while her tomb was located in the Valley of the Kings. Since the ancient Egyptians believed that the soul continues to live after death, the temple served as a place for commemorating the queen, laying offerings, and worshiping the gods.

The Pyramid of Menkaure and Hatshepsut’s Mortuary Temple are masterpieces of ancient Egyptian architecture, which help to understand the ancient Egyptians’ culture, customs, and values. Even though these structures were built at different periods, looked dissimilar and served diverse purposes, both show that religion was a principal value in the life of the Ancient Egyptians. Such masterpieces were created due to the belief in the afterlife. Rituals, offerings, wall ornaments, wealth in chambers, worship of deities, powerful statues and obelisks are evidence of the inextricable connection of Egyptians with deities. Incomprehensible architectural structures like mentioned pyramid and temple seem to be proof of divine intervention, not otherwise.

Bibliography

Agai, Jock Matthew. “The role of the ancient Egyptians beliefs in the afterlife in preserving the ancient Egyptian cultural heritage.” Journal of Languages and Culture, vol. 11, no. 1, 2020, pp. 17-23. Web.

Pawlicki, Franciszek. The Main Sanctuary of Amun-Re in the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Dahari. Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw, 2017.

Sabbahy, Lisa K. Kingship, Power, and Legitimacy in Ancient Egypt: From the Old Kingdom to the Middle Kingdom. Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Verner, Miroslav. The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture and Science of Egypt’s Great Monuments. Grove Press, 2001.