Introduction

The Holocaust left behind severe wounds that took a long time to heal. Among the survivors, many did not return home because someone lost their family or neighbors condemned someone. As a result, by the end of the 1940s, thousands of refugees, migrants, and former prisoners of war were wandering around Europe (Ebbrecht-Hartmann et al. 2021). Not only did the Holocaust nearly wipe out the entirety of Jewish families, but it also split them apart and left the remaining Jewish people struggling to fit back into civilization again because of social death, disconnection from their families, and pogroms.

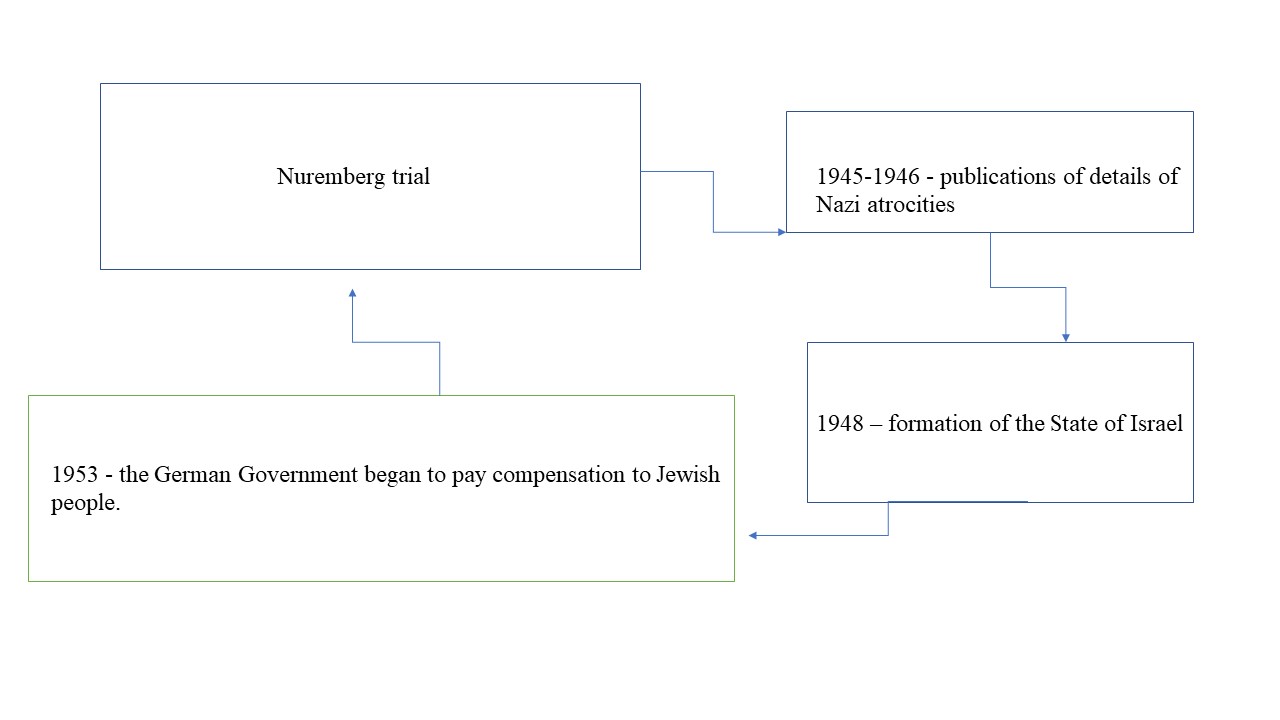

The Course of Events After the War

As can be seen in Figure 1, trying to punish the perpetrators of the Holocaust, and indeed the entire war, the Allies organized the famous Nuremberg trial. In 1945-1946, several war criminals were publicly interviewed, and details of Nazi atrocities were made public (Bergman et al. 2021). In 1948, the pressure on the allied powers intensified — it was necessary to create a national hearth or a sovereign homeland for Jews, victims of the Holocaust (Bergman et al. 2021). As a result, the State of Israel was formed.

In the following years, the Germans struggled with a heavy legacy for a long time. The surviving prisoners and Jewish family members sought to return the wealth and property that the Nazis had confiscated. Since 1953, the German Government, in recognition of responsibility for crimes, began to pay compensation to the Jewish people.

The Tragedy of Jewish Refugees

The world had already heard Hitler’s threats against Jews and knew about the terror staged in the Third Reich. All over the world, they knew about the boycott of Jewish shops, the burning of Jewish and other literature objectionable to the Nazis, the dismissals of Jews and bans on professions, the looting of their property, and mass anti-Jewish propaganda. The world was also informed about the Nuremberg laws, which, along with other racist measures, aimed to expel as many Jews as possible from the country. By the end of 1938, about 150,000 Jews had left Germany — a quarter of the entire Jewish population of this country. After the Anschluss of Austria, another 33,000 Jews went to the unreliable path of refugees (Kimron et al. 2019). Only a few countries have expressed a desire to help them.

Czech Refugees

The situation of Czech Jews was difficult. The intensification of the persecution of German and Austrian Jews led to a sharp increase in their emigration (Kimron et al., 2019). From February to May 1939, about 70,000 people emigrated from these countries, which added difficulties in settling in a new place (Ebbrecht-Hartmann et al. 2021). After the end of the Holocaust, many of them were separated from their families.

Polish Refugees

300,000 Polish Jews managed to survive; 25,000 of them did so in Poland, 30,000 did so after being released from concentration camps, and the remainder came from the USSR. The majority of Polish Jews were obliged to flee the nation, usually by traveling illegally to Central Europe, due to the loss of Jewish life, the devastation, and the expansion of anti-Semitism, which peaked at the Kielce pogrom in July 1946. Only 50,000 Jews were still present in Poland after 1946 (Bergman et al. 2021). Not only were people destroyed — the unique local Jewish culture was destroyed, and the memory that had been an integral part of the culture of Eastern Europe for centuries was destroyed. There is practically no evidence of it left. Jews in these lands, once the center of world Jewry, have become a marginal minority.

Homelessness

In July 1938, an international conference on the Problems of Jewish Refugees, which met in the French city of Evian at the initiative of American President F. D. Roosevelt, tried to alleviate the suffering of the homeless. The negotiations, which representatives of 32 countries attended, ended in vain (Payne and Berle 2021). However, The United States, Great Britain, and several other countries have increased quotas for accepting Jewish refugees who could arrive there if very strict requirements were met.

However, all these measures only slightly weakened the coming tragedy. In the spring of 1939, the British Government significantly restricted Jewish immigration to Palestine (Ebbrecht-Hartmann et al. 2021). Ships with refugees often could not get to Eretz, Israel, for weeks and months. After the end of the war, the number of poor and homeless among Jews also remained extremely high.

Recreating Jewish Communities: Pogroms & Anti-Semitism

The first Jewish community in Germany was recreated in Cologne while the war was going on – in April 1945, under the auspices of the American military administration. In Berlin, German Jews reappeared on the streets on May 9, 1945 – the morning after the surrender of the German army (Ariely 2019). By the summer, there were about 6-7 thousand Jews in the German capital – most of them were not deported because they were married to Aryan spouses (Greenblatt-Kimron et al. 2021). However, about a thousand survived Nazism illegally; communist emigrants from the USSR and other countries returned. The attitude towards German Jews in post-war Germany was fearfully respectful.

However, in 1946, the actual German Jews were already only a small part of the Jews who were in Germany. By this time, Germany, and especially the American occupation zone, had become a transit point for Eastern European Jews who did not want to stay in Poland or the USSR and were rushing to the Country of Israel or America. Displaced persons camps appeared in the zones of American and British occupation, in which the majority were Jews from pre-war Poland (Kimron et al. 2019). Among them were both those who survived the Nazi labor camps and those who survived the war in the USSR and made an unsuccessful attempt to return to Poland and establish their lives in it. The flow of Jewish refugees from Poland has especially increased after the pogrom in Kielce.

It was the Eastern European Jews who inhabited the displaced persons camps that became the object of hatred of ordinary Germans. They reminded the Germans of the pre-war Ostuden. The Germans were annoyed that the Jews in such camps received more rations than the German townspeople. In March 1946, a tragic incident occurred in a displaced persons camp in Stuttgart (Payne and Berle 2021). To identify the speculators, 200 German policemen with dogs and weapons, accompanied by several Americans from the military police, broke into the camp and tried to arrange a search (Bergman et al. 2021). A scuffle ensued, the police began shooting, and a German policeman killed Shmuel Danziger, who had survived Auschwitz and Mauthausen and had found his wife and children only the day before.

After the incident in Stuttgart, the Americans banned German police officers from opening fire in displaced persons camps. Nevertheless, in May 1946, the incident was repeated in the Fernald camp, where a German policeman killed a twenty-year-old Jew who had survived the German labor camps (Bergman et al. 2021). Gradually, in 1947-1948, irritation against German Jews also grew in Germany (Ebbrecht-Hartmann et al. 2021). Denazification deprived many pre-war administrative workers, lawyers, judges, and teachers of the right to work in their profession, and Jewish lawyers and teachers did not experience such difficulties.

With the proclamation of the Federal Republic of Germany, the control of the American military administration over the German authorities ceased, and anti-Semitism was, to some extent, legitimized. The police began to deal more brutally with Jewish speculators and, at the same time, with Jewish demonstrators (Ariely 2019). An increase in anti-Semitism marked the years 1948-1949.

In August 1949, the liberal newspaper Sueddeutsche Zeitung published four letters from readers in response to the statement of the US High Commissioner McCloy that the measure of the democratic revival of Germany would be the development of a new attitude of Germans toward Jews (Kimron et al. 2019). The fourth of the letters, signed with the pseudonym Adolf Bleibtreu, was anti-Semitic. The newspaper did not comment on this letter, which left the impression that this was the editorial board’s opinion.

A demonstration of Jews, most of whom were refugees from Eastern Europe, began in Munich. Mounted police were thrown against the demonstrators. They mercilessly beat them with batons. In response, the demonstrators set fire to a police bus. Later, the Jews of Germany were expected by an anti-Semitic campaign and the purge of Jews from the Socialist United Party of Germany, the ruling party of the GDR, in 1951-1952 (Bergman et al. 2021). Epidemics of anti–Semitic graffiti and desecration of synagogues in Germany in the 1950s and other episodic manifestations of anti-Semitism began.

Conclusion

Therefore, the Holocaust destroyed Jewish families as a whole, split them up, and left the remaining Jews struggling to reintegrate into society due to social death, separation from their relatives, and pogroms. The international community must act to prevent the intentions aimed at the repetition of the genocide. As long as the world remembers the Holocaust, it will resist any new attempt to commit genocide against Jews or another group of people.

References

Ariely, Gal. 2019. “National Days, National Identity, and Collective Memory: Exploring the Impact of Holocaust Day in Israel.” Political Psychology 0, no. 0: 1–16. Web.

Bergman, Yoav, Maytles, Ruth, Frenkel-Yosef, Maya, and Amit Shrira. 2021. “Activity Engagement and Psychological Distress Among Holocaust Survivors During the Covid-19 Pandemic.” International Psychogeriatric 18, no.1: 1–8. Web.

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Tobias. 2021. “Commemorating from a Distance: The Digital Transformation of Holocaust Memory in Times of Covid-19.” Media, Culture & Society 43, no. 6: 1095 – 1112. Web.

Greenblatt-Kimron, Lee, Shrira, Amit, Rubinstein, Tom, and Yuval Palgi. 2021. “Event Centrality and Secondary Traumatization among Holocaust Survivors’ Offspring and Grandchildren: A Three-Generation Study.” Journal of Anxiety Disorders 81, no 1: 1–9. Web.

Kimron, Lee, Marai, Ibrahim, Lorber, Abraham, and Miri Cohen. 2019. “The Long-Term Effects of Early-Life Trauma on Psychological, Physical and Physiological Health Among the Elderly: The Study of Holocaust Survivors.” Aging & Mental Health 23, no. 10: 1340–1349. Web.

Payne, Emma, and David Berle. 2021. “Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms Among Offspring of Holocaust Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Traumatology 27, no. 3: 254–264. Web.