Abstract

Sustainability is presented nowadays as a, not to say, solution for the future of “people, planet, and profit”. This approach was already developed almost 30 years ago. (Elkington, s. d.)

After agreeing on the definition of sustainability and sustainable development, I will review how the development of sustainability deemed to be positive on one side could affect negatively on the other side.

To do so, we will identify some relationships between developed countries and developing countries, especially on the African Continent and, more specifically, in the sector of raw materials.

I will then review the composition of the economic ecosystem in terms of business types and size (i.e., the composition of the private sector), and I will try to demonstrate that the sustainability approach is almost reserved for the wealthy organization when it comes to the environmental topic. Tough, we will also observe that organisations may benefit from growth that could lead to sustainable development at first but support sustainability consciousness in a second phase.

I will finally introduce a discussion on the benefit of standards and norms in this environment and will emphasise the importance of control measures.

In conclusion, the reader will be able to perceive the complexity of relationships in the “sustainability ecosystem”, understand the role and importance of norms, and the role and importance of a third-party ensuring conformity assessment to ensure that sustainability could be sustainable with specific conditions.

Introduction

Sustainability is the way forward for the present, near future, and long term. Consumers are more and more demanding. Solutions are existing or are on the way to being discovered to become “greener”. Tough, we are not informed enough nor sure that the products we buy have a positive impact on sourcing origins.

Most of our final consumer goods are manufactured in emerging economies, and those emerging economies get their supply of raw materials mainly from developing countries. Some critical raw materials may be sourced directly by Western economies from developing countries.

Western companies are under pressure mainly from consumers (and partially from Governments) to offer products that are deemed sustainable. More and more efforts are made to recycle, develop new ways of producing, and source more responsibly.

However, providing “greener” products or solutions like in the renewable energy field with solar energy, for instance (mines) or mobility with Electric Vehicles (EV) and their batteries (mines) or the construction sector or furniture Industry with timber (deforestation, illegal trade) may negatively impact the other side of the supply chain especially when raw materials are needed and sourced from developing countries.

These Western companies may source directly through their subsidiaries or through suppliers. Even if most of them, on principle, respect at least the minimum law requirements of the sourcing country, some local Governments may have difficulties enforcing their own law & regulations. Moreover, the management of the supply chain may be challenging for these companies as the informal sector represents between 20 to 65% of the GDP of African countries as per IMF. The informal sector, by definition, is “surviving,” and questions related to sustainability as a whole are not of primary concern.

Though one may consider that business relationships with organisations classified as informal may help these organisations to become formal and therefore enter a virtuous cycle of creating added value and wealth. In the second phase, as these organisations become more organised and willing to seek new customers, they may implement processes to be more transparent, respect human rights, or engage in environmental commitments. For most of them, it becomes mandatory to do so if they want to access and get new markets.

Therefore standards and norms may be introduced as a substitute for failing States when it comes to Health Safety and Environment regulations. This may become a requirement of the purchaser (or even the final consumer) in Western Countries or a “voluntary” approach of the African organisation.

Though, being compliant with any standards or norms (also to which standards?) is worth it only if an independent party assesses the compliance.

Literature review

The United Nations defined, back in 1987, sustainable development as: “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ ‘ (5987our-common-future.pdf, s. d.). This definition is the most simple and common definition used till now. Though, as reminded by Mensah (2019) in its literature review on meaning, history, principles, and pillars of sustainable development, three pillars are now inescapable in the definition of Sustainable Development:

- Economy

- Environment

- Society

(Porter & Linde, 1995) well developed that interaction.

This interaction is also one of the most critical components in the relationship between developed and developing countries. Research made by (Schandl et al., 2018) demonstrates the flow of raw material coming mainly from the South to produce manufactured goods mainly used in the North. In 4 decades, the material extraction has tripled, reaching 70 Bt in 2010. In a different approach, (Copeland & Taylor, 1994) demonstrates the link between trade and pollution between North and South.

However, even if the literature shows that trade has an environmental impact and mainly outside the country where the goods are consumed, it seems that the measurement of impact is still to be improved to be more accurate and relevant (Tukker et al., 2018). Moreover, recent research tends to demonstrate that Sustainable Development Goals tend to support more economic growth than the sustainable use of resources (Eisenmenger et al., 2020).

However, it is important to note that the environmental issues in Africa are not only linked to international trade or mineral extraction, as demonstrated by Sarkodie et al. (2018)

In opposition to developed countries, the private sector in developing countries is mainly located on the informal side of the economy. This can represent between 25 to 65% of the GDP as per a report by IMF dated 2017. Obviously, there are noticeable differences between countries (Galdino et al., 2018).

It seems that the private sector in the formal economy has a positive impact on the environment with a specific example of the CO2 emission (Talukdar & Meisner, 2001); this is also supported more generally when it relates to FDI (Bokpin, 2017). However, as the informal economy is not regulated and therefore does not follow any law or regulation or standard the result of this analysis could have a huge limitation.

As we have previously mentioned, the informal sector in many countries is very important; one of the reasons is due to the “absence” of the State governments. This absence also leads to having a substitution of rules (or even a creation of non-existing rules) by adopting standards to organise a domain, harmonise approach and/or products, and answer to civil society concerns (Castka et al., 2020; Hiete et al., 2019) or to be able to access international market.

However, the diversity of the Voluntary Sustainability Standards, either supported by ISO or by professional groups, tends to create confusion and refrain some firms from adopting any of these standards (Montiel et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the commitment of firms to comply with these standards has a positive impact on sustainability, either globally or locally.

Finally, it is paramount that such organisations are audited and certified by independent certification bodies in order to ensure the compliance of the actions taken vs. the standards (Ikram et al., 2021).

Methodology

After having reviewed several academic articles on the topic of sustainability in Africa and, in particular, in the forestry industry, I have collected data in regards to the conducted research. The systematic literature review facilitated access to secondary data obtained through the peer-reviewed sources mentioned prior. Namely, the descriptive information will be examined, and a pattern will be identified. The aim is to determine how sustainability is being addressed in African organisations, the limitations that it correlates with, and how both international trade and the informal economy correlate with the concept of sustainability. Moreover, the methodology implies the analysis of research regarding specific ways in which the private sector and state entities address the topic of ethical sourcing of raw materials and other aspects of production, which are known to be often addressed without regard to sustainability.

The descriptive overview of the research, while limiting the findings when it comes to direct correlational relationships, will help assess a multitude of topics regarding sustainability in African organisations. Initially, the methodology will be based on the topic of the relationship between African organisations and developed countries. Namely, the goal is to determine how trade relationships either facilitate or disrupt national sustainability goals. The assessment will be based on a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Hence, reliable sources will be observed to determine a pattern. The focus of this section will be raw materials, namely, ones acquired by African organisations and sold to organisations (public or private) in developed countries. Moreover, the descriptive content will be examined in relation to the economic ecosystem on the African continent. The topic, likewise, will be examined through reliable data and research conducted by authors and organised in peer-reviewed articles. Last but not least, the chosen methodology will facilitate an assessment of how norms and standardised guidelines either compromise or facilitate organisations to become more eco-conscious and sustainable in the sourcing of raw materials and production of goods.

The aforementioned subject will be examined through the existing research highlighting the outcomes of the implementation of such norms. The results will be processed, and the descriptive content will be synthesised through a systematic review. The proposed methodology will provide relevant evidence on the topic similar to the findings generated through a meta-analysis. However, no statistical overview will be conducted since the methodology is aimed toward a better understanding of sustainability in African organisations rather than an examination of statistical overviews of various factors. Moreover, while the systematic review will provide a broader view of the complexity of sustainability, the method ensures objectivity. Objectivity is achieved through the use of peer-reviewed sources published in reliable journals and based on either direct experimentation or research based on indirect sources. Hence, the methodology selected for the present research will facilitate objective results despite the complexity of the topic and the multiple aspects that are to be analysed in relation to sustainability.

Empirical Results

As mentioned prior, the initial topic which is to be assessed empirically is the relationship between African organisations and developed countries in regard to the trade of raw materials.

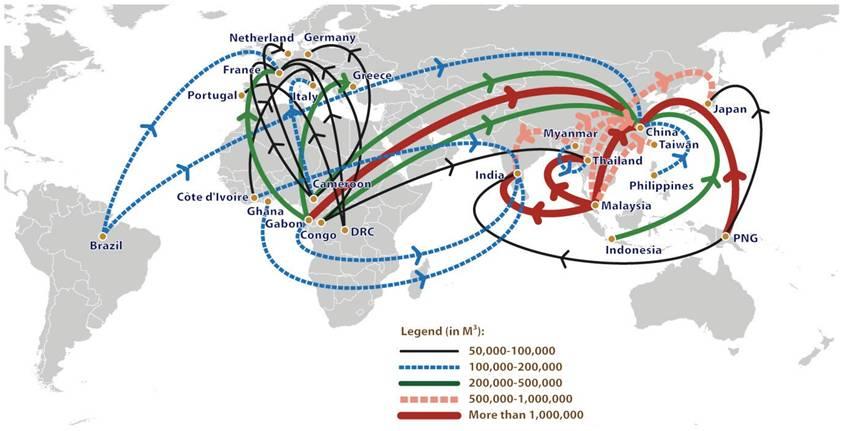

The below map demonstrates the commerce of tropical woods, which are mainly coming from the African continent and being shipped to either western Europe or Asia (mainly China). The image below highlights that more than 1,000,000 m3 of tropical wood is shipped to China, making the country the biggest importer. The factor correlates with the recent aims to address sustainability in China. Certain bans on deforestation ensure wood export increases by 15,2% (Zhang & Chen, 2021).

Thus, African organisations specialising in the wood trade manage the demand by exporting 1,000,000 m3 of wood to the aforementioned region. According to researchers, while China is the biggest importer of wood, it is also the biggest exporter. This. However, this does not stop the country from purchasing 4,898,521 m3 of wood products from the Republic of Congo alone between 2007 and 2019 (Ondze et al., 2021). The numbers highlight the major trade relationships between African organisations and developed nations based on the commercialization of raw products such as tropical wood. Needless to say, similar trends have been observed in relation to the export of the said product in Europe (200,000 – 500,000 m3). This also highlights the high demand, which will later be examined in relation to sustainability practices. The empirical data mentioned prior is an illustration of the existing trade relationships between Africa and developed countries, which are facilitated by the demand for raw materials.

Another empirical data that is to be examined links sustainability with the economic system in Africa since certain individual traits have to be considered based on the complexity of the issue. Researchers highlight that 90% of the lowest-paid jobs in Sub-Saharan countries are facilitated by the extensive presence of an informal economy, and, as mentioned prior, 25 to 65% of the GDP is also constructed through informal organisations within the private sector (Galdino et al., 2018). The numbers are extremely high since it is certain that the majority of the private sector consists of businesses that are not regulated, taxed, or held accountable in regard to sustainability. Empirical data in regards to how informal organisations directly affect sustainability goals in relation to sourcing and trading raw materials is challenging to obtain. The concept is difficult to measure due to the implications linked to informal organisations. Such entities are difficult to research since they are not registered, and the adherence to sustainability objectives is not regulated. Instead, such businesses can self-regulate through voluntary implementations of concepts such as sustainability.

Empirical data is also to be assessed in regards to the variables of readiness for climate change and the percentage of forest area covering countries on the African continent. The results show that while countries such as The Democratic Republic of Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, Cameroon, and Senegal have major resources of forest covering extensive territories (67,3%; 32,7%; 38,2%; 39,8%; and 43%, respectively), the countries are in the red zone (Sarkodie et al., 2018). As a result, the findings link unsustainable use of wood to pollution and negative effects on readiness for climate change. Such findings may correlate with the lack of trees to transform carbon monoxide into oxygen or a structural change in the social and economic lives of the countries.

Based on empirical data on the increase in demand for raw products, the aforementioned data on the wood trade will be more critical. Researchers highlight that the average extraction of raw material per capita was 7t in 1970 and has increased by 3t (Schandl et al., 2018). Thus, the current population individually makes up for 10t of material extraction, an increase of 42 percent, which is unprecedented. Needless to say, as the global population increases at fast rates, the extraction of materials measures will skyrocket in the next decades. This can have a major toll on sustainability in the private sector in African countries, especially due to the growing financial potential of the Chinese population and the fast development of the country, which is already the biggest importer of wood.

Analysis

After conducting an in-depth systematic review of the literature and examining the empirical data on both African organisations’ involvement in world trade and the effect on sustainability, certain aspects of the correlation have been determined. The initial aim was to determine the factors that facilitate Africa’s export of raw materials, especially wood. It has been determined that China is the biggest buyer of all wood products showcased on the market by African organisations. On the other hand, China implements policies related to logging bans as a part of a more sustainable economic environment (Zhang & Chen, 2021). While the initiative ensures African organisations are able to sell raw materials, China itself is a major wood export. As a result, it can be highlighted that the reason why China, while having natural resources and selling them, acquires wood from Africa is because of the informal economic entities. Said organisations offer products without implementing sustainability guidelines, which ultimately negatively affects both the economic and the ecological environment. As mentioned prior, the environment goes hand in hand with the economy and society (Porter & Linde, 1995). A disregard for one pillar creates a precedent in which the link between the three is disrupted.

The analysis highlights that the trade of raw materials is a major part of the private sector in the economies of multiple African countries. However, the exportation of said goods has not been disregarded as a threat but rather as an opportunity to implement regulations and more rigid policies in regard to sourcing. When the relationship between three concepts of sustainability, namely, the economy, environment, and society, is disregarded, all three entities are damaged (Porter & Linde, 1995). Thus, excessive deforestation as a result of unethical sourcing and trade of wood will later have a negative effect on the environment. On the other hand, the lack of tax regulations in regard to informal organisations affects the economy, as well as the damage created through said practices. As a result of the environmental and economic challenges, the social aspect will also deteriorate. Moreover, based on the data examined in regards to trade relationships with Asia and Western European countries, a pattern can be highlighted. The said nations have regulated norms in relation to the sourcing of raw materials. On the other hand, the national sustainability goals are not extended toward the sustainability objectives of the goods acquired from abroad. As a result, developing countries on the African continent are subjected to more environmental hardship in fulfilling the consumer needs of the developed countries. While one environmental agenda is put in place, the result is the disregard of the efforts of the second party. This is partially facilitated by the less solid economy of African countries as well as the major influence of informal entities contributing to national economies.

The economic ecosystem briefly mentioned prior is a major concern in relation to sustainability goals. Since, in some instances, more than half the economic sector of a country consists of non-registered businesses, it is essential to consider the concept as a direct contribution to a lack of adequate sustainability measures (Galdino et al., 2018). There are several attributes to informal organisations that are to be discussed. On the one hand, such businesses are a major part of national economic systems and contribute to a country’s financial objectives. As a result, it is certain that abolishing said sector altogether would have major economic implications if executed.

Since certain countries almost solely rely on informal income (60% in certain instances), implementing rigid regulations would lead to a major economic downfall, high rates of unemployment, and impoverishment. On the other hand, informal organisations are often operating in the process of sourcing raw materials and trading them both nationally and internationally. Such practices, if not regulated and supervised by authorities or relevant entities, are often unsustainable. Due to a lack of regulations, organisations disregard environmental concerns in order to maximise profit. Hence, excessive deforestation, mining, agricultural work, and similar processes assist in the acquisition of raw materials.

One way in which researchers mention that informal and formal economies can be assisted in relation to sustainable practices is with the implementation of standards and norms. Said norms can be applied to the internal environment, external environment, or voluntary. An example of norms adopted within the external environment is the agreement among developed countries in regards to investment in raw materials. According to researchers, high stakeholder demand is one of the contributing factors to the lack of sustainability norms in the African mining industry (Hiete et al., 2019). Thus, high demand creates circumstances in which the organizations are to mine excessively and acquire more raw materials, ultimately disrupting the sustainable practice. On the other hand, the global community is to have a quota on investing in said materials, and entities are to ensure the practices used during the processes fall in line with environmental agendas.

Internal regulations are the norms that governments can implement on a national or regional level. However, due to the major impact of the presence of informal economies, it is unlikely that the regulations will be followed and strictly adhered to. This is why an effective measure is the formulation of voluntary measures that organizations can follow. As a result, said companies are to be remunerated with tax cuts, the label of a sustainable producer, and the ability to cooperate with major international buyers. The analysis shows several benefits to the implementation of voluntary guidelines. On the one hand, the organization does not have to be registered to implement said norms. Instead, the businesses operating in the informal domain of the private sector will be able to change their sustainability premises. On the other hand, local change can facilitate bigger stakeholders to consider a similar aim. As a result, sustainability will be obtained through the personal effort of businesses selling raw materials rather than through the complex involvement of national forces such as the government. Hence, the current analysis has determined the role of trade between African companies and developed countries, the specific traits of the unique economic ecosystem, and the importance of norms and regulations implemented on multiple levels.

Conclusion

Sustainability is the consideration of three factors, namely, the environment, economy, and society. A major limitation in regard to sustainability goals exemplified in the case study of African organisations is the internal and external consumer demand for raw materials. It is especially prominent when it comes to trade relationships with Western Europe and Asia, the demand of which facilitates the presence of unsustainable practices when it comes to acquiring wood, mining, and similar processes. The internal environment does not facilitate an environmental agenda either due to the major impact of informal organisations. Informal economies are major financial drivers and can make up for more than half the national economy.

While the sector facilitates employment and reduces poverty, such organisations cannot be adequately regulated. As a result, the aim is to maximise profit despite environmental premises. Since such organisations are challenging to manage from a national perspective, the proposed solution is to implement internal, external, and voluntary norms. The limitation of internal regulations is linked to the complex structure of informal businesses operating alongside registered ones. However, the measures implied that formal organisations would make sustainable changes. Another proposal is addressing the issue of high stakeholder demand, which drives high production. The solution is to implement an international agreement in regards to a quota of raw materials calculated based on sustainability premises. Moreover, developed countries are to ensure relevant entities monitor the efficacy of the sourcing processes or goods they acquire. Last but not least, voluntary norms can be adopted by each organisation despite its formal or informal status. As a result, the private sector will improve as a whole, and sustainability goals will be achieved through the individual effort of each participant.

References

5987 our-common-future.pdf. (s.d.). Consulté 15 octobre 2021, à l’adresse. Web.

Bokpin, G. A. (2017). Foreign direct investment and environmental sustainability in Africa : The role of institutions and governance. Research in International Business and Finance, 39, 239‑247. Web.

Castka, P., externe, L. vers un site, & fenêtre, celui-ci s’ouvrira dans une nouvelle. (2020). The role of standards in the development and delivery of sustainable products : A research framework. Sustainability, 12(24), 10461. Web.

Copeland, B. R., & Taylor, M. S. (1994). North-South trade and the environment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(3), 755‑787. Web.

Eisenmenger, N., externe, L. vers un site, fenêtre, celui-ci s’ouvrira dans une nouvelle, Pichler, M., externe, L. vers un site, fenêtre, celui-ci s’ouvrira dans une nouvelle, Nora, K., Dominik, N., Plank, B., externe, L. vers un site, fenêtre, celui-ci s’ouvrira dans une nouvelle, Ekaterina, S., Marie-Theres, W., Gingrich, S., externe, L. vers un site, & fenêtre, celui-ci s’ouvrira dans une nouvelle. (2020). The sustainable development goals prioritize economic growth over sustainable resource use : A critical reflection on the SDGs from a socio-ecological perspective. Sustainability Science, 15(4), 1101 1110. Web.

Elkington, J. (s. d.). Enter the triple bottom line. 16.

Galdino, K. M., Kiggundu, M. N., Jones, C. D., & Ro, S. (2018). The informal economy in pan-Africa : Review of the literature, Themes, Questions, and Directions for Management Research1. Africa Journal of Management, 4(3), 225‑258. Web.

Hiete, M., Sauer, P. C., Drempetic, S., & Tröster, R. (2019). The role of voluntary sustainability standards in governing the supply of mineral raw materials. GAIA – Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, Suppl. SPECIAL ISSUE: SUSTAINABLE ECONOMY: PERSPECTIVES OF CHANGE, 28(S1), 218‑225. Web.

Ikram, M., Zhang, Q., Sroufe, R., & Ferasso, M. (2021). Contribution of Certification bodies and sustainability standards to sustainable development goals : An integrated grey systems approach. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 28, 326‑345. Web.

Mensah, J. (2019). Sustainable development : Meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: Literature review. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1). Web.

Montiel, I., Christmann, P., & Zink, T. (2019). The effect of sustainability standard uncertainty on certification decisions of firms in emerging economies. Journal of Business Ethics, 154(3), 667‑681. Web.

Ondze, D. B., Tong, M., & Mendako, R. K. (2021). Republic of Congo’ wood products exported to China: Insight of the characteristics, trends, and perspectives for sustainable trade. Open Journal of Forestry, 11(02), 135–152. Web.

Porter, M. E., & Linde, C. van der. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(4), 97‑118.

Sarkodie, S. A., externe, L. vers un site, & fenêtre, celui-ci s’ouvrira dans une nouvelle. (2018). The invisible hand and EKC hypothesis : What are the drivers of environmental degradation and pollution in Africa? Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 25(22), 21993‑22022. Web.

Schandl, H., Fischer‐Kowalski, M., West, J., Giljum, S., Dittrich, M., Eisenmenger, N., Geschke, A., Lieber, M., Wieland, H., Schaffartzik, A., Krausmann, F., Gierlinger, S., Hosking, K., Lenzen, M., Tanikawa, H., Miatto, A., & Fishman, T. (2018). Global material flows and resource productivity : Forty years of evidence. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 22(4), 827‑838. Web.

Talukdar, D., & Meisner, C. M. (2001). Does the private sector help or hurt the environment ? Evidence from carbon dioxide pollution in developing countries. World Development, 29(5), 827‑840. Web.

Tukker, A., Giljum, S., & Wood, R. (2018). Recent Progress in assessment of resource efficiency and environmental impacts embodied in trade : An introduction to this special issue. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 22(3), 489‑501. Web.

Zhang, Y., & Chen, S. (2021). Wood trade responses to ecological rehabilitation program: evidence from China’s new logging ban in natural forests. Forest Policy and Economics, 122, 102339. Web.