Introduction

The phenomenon of interest (POI) for this analysis is managing stress among the population of parents with children hospitalized with a terminal illness. The selected concept analysis article (CA) by Smith (2018) analyzes and devises the principles of family-centered care (FCC) in the medical setting. Smith (2018) concludes that clarifying the characteristics of operational principles of the FCC, in conjunction with educating staff on the topic, can potentially facilitate its further integration in the hospital environment. This paper aims to analyze the FCC principles and determine which ones healthcare providers (HCPs) can implement for stress management in the population of parents with pediatric terminal patients.

Concept Analysis

Theory Origin

The historic mode of patient care discouraged, if not prohibited, parents from visiting their hospitalized children (Smith, 2018). Soon after that, the detrimental effects of parent-child separation during hospitalization were revealed, so a movement ensued to challenge the ancient notions of care (Smith, 2018). Presently, FCC aims to provide care standards and recommendations for HCPs to recognize and support the family as a cohesive unit rather than separate individuals (Smith, 2018). The FCC guidelines include a conceptual framework within health care delivery that promotes family involvement, partnership and collaboration between the family and the HCP team, transparent information exchange, and open visitation (Smith, 2018). Smith (2018) suggests that implementing a holistic family approach is vital to improving pediatric patient outcomes, reducing family stress factors, and enhancing families’ lived experiences. However, Smith (2018) states that these guidelines remain an abstract concept, not adequately meeting families’ physical and emotional needs. Hence, the purpose for conducting the CA was to deliver the change nursing practice requires – from a patient-illness care model to a collaborative and explicit patient-family-oriented model.

Relevance and Transferability

The CA is relevant to the POI in question because FCC provides many foundational aspects for family-based stress management. Smith (2018) concludes that family stress can be decreased through FCC-facilitated reciprocal respect, open communication, and collaboration in patient care. Moreover, the need to monitor parental stress comes from the accumulated scientific understanding that supporting, consulting, and involving family members plays a major role in pediatric nursing care. Children are dependent on their families, especially their parents, to meet their physical, emotional, and social needs (Foster et al., 2017). Parents’ reduced capacity to meet their child’s needs affects the healing of the latter negatively, and thus the well-being of the entire family can be threatened, including other children (Foster et al., 2017; Yi-Frazier et al., 2017). Therefore, applying the FCC principles is relevant for terminal illness cases and beyond.

The FCC concept has great transferability and can be implemented across various settings. For instance, parental stress and the subsequent varyingly successful coping techniques impact the outcomes of pediatric patients with terminal or critical illness, injury, or congenital disabilities (Yi-Frazier et al., 2017; Woolf‐King et al., 2017; Foster et al., 2017). Foster et al. (2017) have discussed instances of supporting parents whose children have faced a physical injury and were in the acute hospital phase. The same FCC principles guide Foster et al.’s (2017) recommendations for major trauma family support, with the case-specific foci of navigating the crisis of child injury, coming to terms with its complexity, and meeting the family’s needs. Moreover, upon examining the parents of children with critical congenital heart defects (CHDs), Woolf‐King et al. (2017) found them at an elevated risk for mental health problems. Therefore, Woolf‐King et al. (2017) highlight the importance of the FCC model that incorporates empirically supported mental health screening and interventions into cardiac patient care. Overall, the FCC practices are relevant for managing parental stress in acute and prolonged pediatric care settings.

However, there may be some limitations to applying certain FCC principles. In evaluating the FCC experience of parents with children stationed in a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), Hill et al. (2018) find mixed feedback, negative aspects mainly concerning parents feeling lost and anxious once introduced to the PICU setting. As Abela et al. (2020) specify, the main parental stressors in PICU included the sights and sounds, changes in the family dynamic and function, and uncertainty of the pediatric patient outcome paired with compromised alertness. While the uncertainty of outcome is not applicable in terminal pediatric patients, parents arguably may experience more stress given the uncertainty of predictions – not knowing when their child may pass. However, further research is necessary to evaluate the relevance and impact of this particular aspect. Hence, while FCC ethics aid HCPs in reducing parental stress, the core concepts should be refined to address the care environment’s importance explicitly.

Major Concepts

Scholarly literature research has created an interdisciplinary framework identifying four major concepts of family-centered care. The first FCC concept embraces dignity and upholds healthcare providers’ (HCPs) respect for the patient and family choices and opinions (Smith, 2018; Hill et al., 2018). This concept emphasizes consideration and incorporation of a child’ and parents’ unique choices, values, and cultural background in providing care (Smith, 2018). The second FCC concept is information sharing, which entails HCPs communicating and sharing complete and objective information with patients and families in helpful and affirming ways (Smith, 2018; Hill et al., 2018). Patients and families should receive timely, complete, and accurate information to embrace the third FCC concept effectively: their participation in care and decision-making, depending on their preferred comfort level (Smith, 2018; Hill et al., 2018). Finally, the FCC encompasses the concept of true collaboration between pediatric patients, their families, HCPs, and even authorities (Smith, 2018; Hill et al., 2018). All the parties may collaborate, to various extents, developing, implementing, and evaluating care policies and programs, designing facilities, educating, and delivering care (Smith, 2018). Although various combinations exist, the above concepts are the most comprehensive ones.

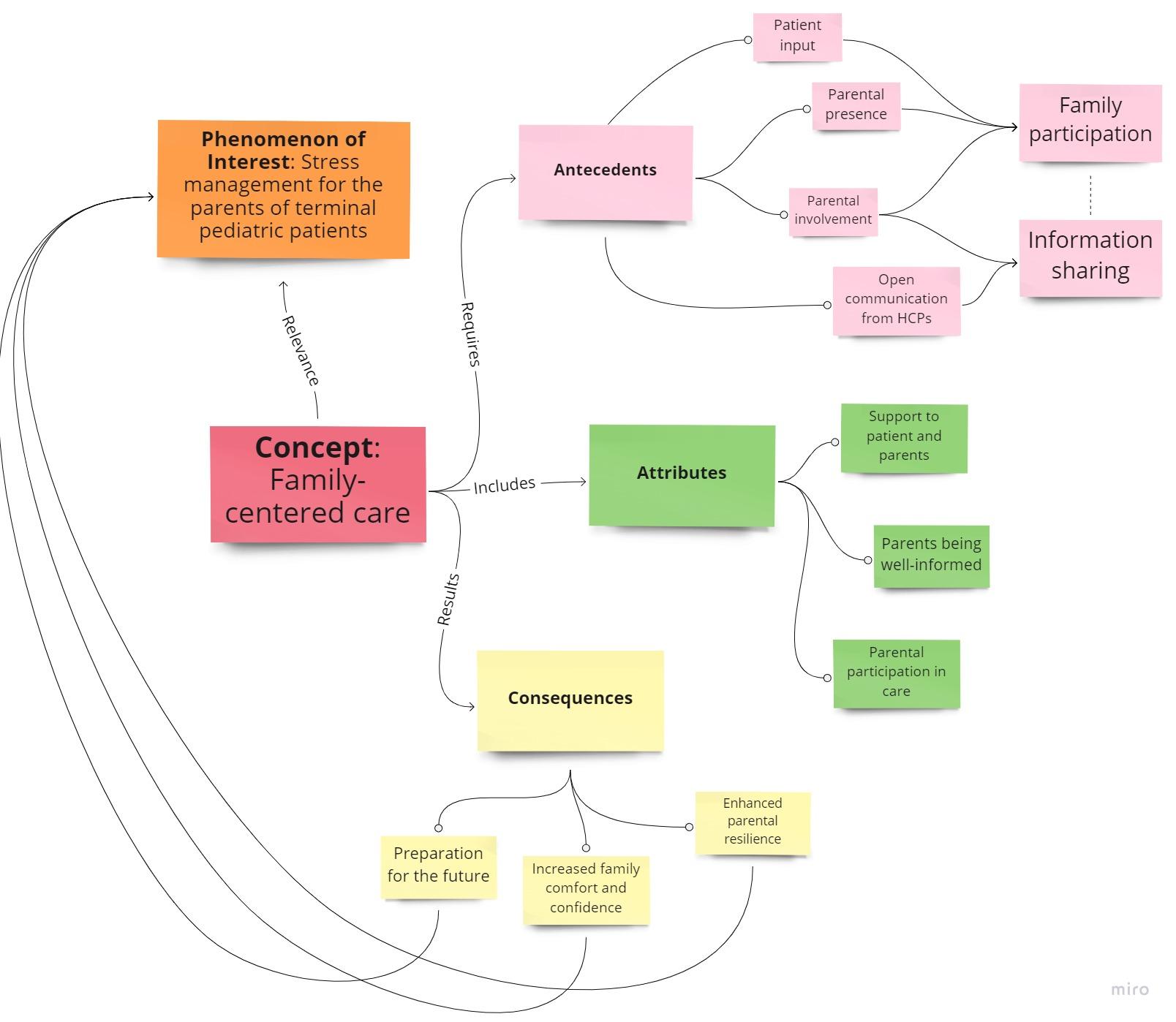

Antecedents

Several factors are most commonly identified as causes of the successful FCC implementation. The major antecedents from the family side listed by Smith (2018) were the parental presence and willingness to collaborate and participate. Indeed, in investigating a resilience-promoting intervention for more effective stress management in parents of adolescents and children with type 1 diabetes or cancer, Yi-Frazier et al. (2017) conclude that family-based efforts improve resilience in the medical setting. From the staff side, HCPs’ competency and willingness to negotiate care aided the process (Smith, 2018). Lastly, the FCC approach thrived within an environment conducive to the family’s presence and participation and sufficient time for communicating and developing parent-HCP relationships (Smith, 2018). The most common need of parents was to be well-informed on the treatment process. As Hill et al. (2018) discuss, HCPs invoking the most trust are those who ask for parental opinions and observations and create an environment where parents could be physically present and involved. Hence, the listed antecedents may effectively predict the lower incidence of parental stress due to more trusting relationships and increased family resilience.

Attributes

Nurses may exhibit FCC in several ways to manage parental stress. The attributes listed by Smith (2018) were respect for unique family characteristics, the support provided to patients and parents, parent participation in care at their comfort level, open communication, HCP-parent partnerships, and cultural competence and appreciation. Abela et al. (2020) find that parents whose children were in PICU most commonly needed to be well-informed about the course of action. Hence, attributes like open communication and participation are crucial for ensuring comfort and managing stress. This finding is especially applicable in cases of terminal illness since the uncertainty may exacerbate parental anxiety about the future. Additionally, in the case of parents with children who have special complex healthcare needs, Bradshaw et al. (2019) underline the importance of providing support and upholding partnerships. However, it is unclear whether every specific FCC attribute applies to the families facing a terminal diagnosis. Attributes like cultural appreciation may play a large role, especially in evaluating family beliefs regarding death acceptance, but more research is needed. Although a comprehensive investigation is required for some aspects, FCC attributes are still largely relevant in managing parental stress.

Consequences

Implementing FCC principles in medical settings can be classified into several major categories. The consequences listed by Smith (2018) were individualized, flexible care, increased family comfort and confidence, increased parent-HCP communication, strengthened adaptation and function, improved satisfaction, and parental empowerment. Indeed, Stremler et al. (2017) show that higher levels of social support are protective among the parents of children in PICUs with severe anxiety, depression, and significant decision-making conflicts. Therefore, upholding these FCC principles increases parent comfort, confidence, decision-making, and coping capacity. However, Watson et al. (2018) state that detrimental psychological outcomes for families may persist for years after the PICU experience. Hence, while consequences of the FCC implementation are already beginning to be recorded in the literature, the long-term effects are subject to further research. One crucial outcome of FCC techniques is therefore strengthened adaptation and function. Yi-Frazier et al. (2017) discuss how FCC may be a feasible method for building resilience and reducing distress, which may benefit parents in the long term. This note is particularly relevant to the POI since it eventually entails parents handling the grief of losing their child.

Conclusion

To conclude, certain family-centered care principles should be used by healthcare providers in order to mitigate parental stress in the situations where their child battles terminal illness. The well-being of pediatric patients and their parents are tightly interlinked, and therefore the research calls for a holistic approach to treatment. Information sharing and participation are highlighted as the most important concepts for the parents whose children were in critical condition. Hence, the antecedents for successful FCC implementation are parental presence and involvement, communication from HCPs on patient prospects, incorporation of patient observations, and HCP’s willingness to collaborate. It is a little challenging to devise specific attributes of FCC relevant to the POI, but the most important ones are supporting patients and parents, parents being well-informed, and parental participation in care. The major consequences of FCC implementation, in this case, would be increased family comfort and confidence during the care process and enhanced resilience which would prepare parents for the future. Overall, managing stress in parents of terminal pediatric patients should come with great openness and empathy from the nursing staff.

References

Abela, K. M., Wardell, D., Rozmus, C., & LoBiondo-Wood, G. (2020). Impact of pediatric critical illness and injury on families: An updated systematic review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 51, 21–31. Web.

Bradshaw, S., Bem, D., Shaw, K., Taylor, B., Chiswell, C., Salama, M., Bassett, E., Kaur, G., & Cummins, C. (2019). Improving health, well-being and parenting skills in parents of children with special health care needs and medical complexity – a scoping review. BMC Pediatrics, 19(1), 301. Web.

Foster, K., Young, A., Mitchell, R., Van, C., & Curtis, K. (2017). Experiences and needs of parents of critically injured children during the acute hospital phase: A qualitative investigation. Injury, 48(1), 114–120. Web.

Hill, C., Knafl, K. A., & Santacroce, S. J. (2018). Family-centered care from the perspective of parents of children cared for in a pediatric intensive care unit: An integrative review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 41, 22–33. Web.

Smith, W. (2018). Concept analysis of family-centered care of hospitalized pediatric patients. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 42, 57–64. Web.

Stremler, R., Haddad, S., Pullenayegum, E., & Parshuram, C. (2017). Psychological outcomes in parents of critically ill hospitalized children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 34, 36–43. Web.

Watson, R. S., Choong, K., Colville, G., Crow, S., Dervan, L. A., Hopkins, R. O., Knoester, H., Pollack, M. M., Rennick, J., & Curley, M. A. Q. (2018). Life after critical illness in children —toward an understanding of pediatric post-intensive care syndrome. The Journal of Pediatrics, 198, 16–24. Web.

Woolf‐King, S. E., Anger, A., Arnold, E. A., Weiss, S. J., & Teitel, D. (2017). Mental health among parents of children with critical congenital heart defects: A systematic review. Journal of the American Heart Association, 6(2). Web.

Yi-Frazier, J. P., Fladeboe, K., Klein, V., Eaton, L., Wharton, C., McCauley, E., & Rosenberg, A. R. (2017). Promoting resilience in stress management for parents (PRISM-P): An intervention for caregivers of youth with serious illness. Families, Systems & Health: The Journal of Collaborative Family Healthcare, 35(3), 341–351. Web.