Introduction

Public spaces may easily be attributed to governance planning and design, although most often than not, have been criticized for failing to consider many aspects of reality: human existence and sustainability, environmental concerns, and other spoken and otherwise contempt for such failures.

It is to be understood that public spaces are areas, indoors and outdoors, accessible and open for use or occupation if only temporary, to a taxpayer, and that is everyone. In traditional cases, it had been that public spaces simply existed for the exigency of “public service,” and it had not been previously important as to how or who designed such space, edifice, lay-out, or the visual entity of a given area.

What had been important was its accessibility for use by the public, to its’ supposedly clients. Nevertheless, there had been public spaces that rendered interest to the public if only for its aesthetic appearance, functionality or practicality of a design previously unseen or unheard of, and this interest has grown as designers or architects prove their importance and capacity to raise curiosity and liking, not only to the public but also to the people behind government systems.

This paper will try to explore as to what extent is the privatization of public spaces addressed from an architecture or urban design point of view in consideration of urban design, public space, and privatization.

Discussion

Public Spaces

Public space has been defined as a space characterized by the presence of strangers or different peoples or groups of which interpersonal spheres of sociability and varied activities are observed (Lofland, 1998). Its accessibility, however, does not equate to deletion of boundaries (Karrholm, 2007), although the public or citizens attach value on it through the expression of attitudes, asserting of the claim and using it for their own purposes (Goheen, 1998).

As such urban public space is characterized by proximity, diversity, and accessibility (Zukin, 1995). Boyer (1996), however, noted that the modern city has evolved to offer an increasingly inhospitable environment for the widespread increase of influence of the private against the public.

It has been noted that some if not many plazas and public places were uninviting spaces and were the unintentional residue or side effect of profit maximization (Whyte, 1988) and elaborately described as “unintended consequences of other processes — architects’ slavishly reproducing modernist architectural styles, or developers’ minimizing costs by neglecting spaces,” (Smithsimon, 2008, p 326).

Privatization

Jacobs (1961) much earlier suggested that public plazas and open spaces are mindless reproduction of aesthetic trappings of modern architecture, of which Smithsimon (2008) argued otherwise as made intentionally uninviting to cater to the needs of their developer-clients.

Other studies ( Kayden et al., 2000 and Carr et al., 1992) also pointed out that accessibility and usability of public spaces and office plazas were outrageously questionable, blamed easily on local governments, and its privatization reflecting corporate interests (Mitchell, 2003).

Smithsimon (2008) have noted the presence of bonus plazas as public spaces that are inclusions in high-rise building projects that include outdoor plazas and indoor arcade, sidewalk widenings, public passageways derived from incentive zooming regulations allowing builders an added floor area ratio (FAR) to develop spaces for public access: a contract between the developer and the city.

In this process, there is the privatization of public space, which remained baffling for the public to use but still attributed as projects of the local governments.

These include post-industrial capitalism restructuring in Glasgow that centered on close-circuit television systems proposed by the city’s development agency and operated by the city’s police department (Fyfe and Bannister, 1998), restriction of use of public space or park for a city’s antihomeless initiatives (Mitchell, 2003), and as Davis (1990) enumerated to include dread-inspired public libraries, town redevelopment schemes displacing residents or other original establishments, “bum-proof” (p 263) benches and police opposition to public toilets.

While Smithsimon (2008) established that “efforts to restrict the public from using spaces actually reflect the prerogative of private (often corporate) actors,” (p 329), the architects and developers were the ones pointed as responsible.

Gans (2006) branded them as workday architects, while Wolfe (1981) protested barren, unwelcoming modern buildings and cities asking, “Has there ever been another place on earth where so many people of wealth and power paid for and put up with so much architecture they detested?” (p 7).

Brain (1991), however, showed that architects were not operating autonomously. There was the aim to privatize such as Flusty’s (1994) observation in Los Angeles that private decision-makers intentionally excluded all but prospective affluent consumers.

Urban Design

Lang (2005) described types of practice based on urban design:

- total urban design – has its designer a core actor in the development team that carries a master plan to completion and has considerable control over the result. This is exemplified by the Brasilia and Manhattan’s Rockefeller Center.

- all-of-a-piece urban design – an urban design team prepares a plan and guidelines that set the rules for developers and their designers. An example would be Shanghai’s Pudong and London’s Paternoster Square.

- piece-by-piece urban design – is policy-based that provides guidelines for a specific precinct of a city in order to encourage cultural or downtown redevelopment. An example of this design in New York’s theater district.

- plug-in urban design – a basic or foundation design is created with future elements seen and considered for addition, such as the case for Curitiba’s busway.

This is not the case, however for the Kansas City project of Elpidio Rocha, an environmental planner-designer which tried to empower the ethnic and working-class as residents of the city through the Center City Plaza designed to provide democratic space for a diverse citizenry.

Rocha’s, however, was pitted against another project by developer J.C. Nichols (see Appendix) influential in modern or urban planning, which included retail shopping, office space, theatres, and residential housing in close proximity many communities still try to duplicate until today (Langdon, 2006).

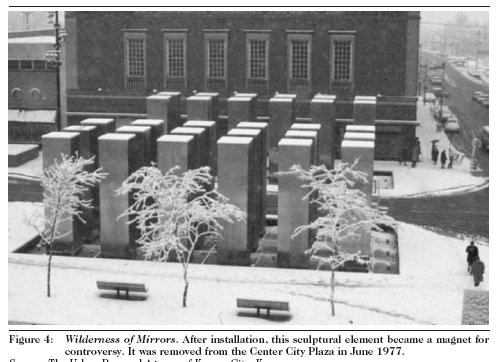

Rocha assembled a team that developed a collaborative design incorporating Mexican culture started with cultural landscapes of the state, imagery of urban and rural environments, as well as working-class and ethnic environments described as “humanized architecture” although the Wilderness of Mirrors, an abstract interpretation of Mexican Poet Octavio Paz’ The Labyrinth of Solitude (Wagner, 2003) did not enjoy continued acceptance in its original location at Minnesota and Seventh Avenue.

Rocha’s design concept, although earlier applauded and widely accepted, has been the victim of political leadership as well as economic needs that should be met. The Huron cemetery remained as its flagship symbol to date.

Privatization of Public Places

Privatization of public spaces is said to have started 1961 in New York as a practice as a bonus to builders, contractors or developers for extra FAR to provide public plaza space at street level in exchange for building larger and taller buildings. This agreement between the city and its citizens with the private developers allows the public to use the space as long as it is not disruptive. Thus the people can access, use, claim, and modify it (Carr et al., 1992).

This practice was modeled after the Mies van der Rohe designed for Seagram in 1958. It is a landmark tower-in-a-plaza. In theory, it provided plazas for the public, a taste of architectural styles or trends, and rational floor plans for tenants.

It captured the ideal for urban design in the mid-twentieth century that created privately owned public spaces imitated throughout the world. While the focus on privatized public spaces maybe on local governments, it is unavoidable to disassociate architects on the responsibility of unusable spaces and urbanists point at modernist style on the failure of plazas (Wolfe, 1981).

It has come to a point where public space is seen to be opposed and restricted by the corporate sector (Whyte, 1998; Kayden et al., 2000). Whyte (1998) wrote, “Ambiguity as to what the developer must provide is an invitation to provide little (p 114).

Other literature was viewed to have difficulty pointing out the responsibility of inadequacies. Whyte’s (1998) aim had been to regulate and suggest an improvement for public space city planning not necessarily mentioning developing but insisting on the use of benches and trees.

Interestingly, while shopping malls were directly associated with developers who pick materials to tenants, skyscrapers were easily seen as towering products of aesthetic architectural genius.

Many studies have pointed out that the vast majority of privatized public spaces are barren, unusable, exclusive and dead space, described as “awful: sterile, empty spaces not used much for anything” (Whyte, 1988, p 234), “Most of the spaces are not working well – certainly not well enough to warrant the very generous subsidies given for them (p 245),” while Kayden et al. ‘s study (2000) noted how the majority of the 503 privatized public spaces in New York failed to attract people.

Earlier, by 1075, the new York City’s Department of City planning noted that “too many have merely been unadorned and sterile strips of cement. These ‘leftover’ spaces are merely dividers of buildings, windy, lonely areas, without sun or life,” (quoted by Smithsimon, 2008, p 333).

Some characterization of privatized public spaces was also noted. An example was that by 1971, sunken plazas were eliminated as people avoided using them. Likewise, paving treatment was required to be uniformed between the plaza and the adjoining sidewalk as passersby understood that a granite courtyard next to a concrete sidewalk is considered separate or a private entity.

While indoor public spaces could have also proved more useful due to its possibility for climate control and usefulness all-year-round, city planners concluded that glassed-in spaces without explicit signs and large doors these were considered private and avoided by the public.

Smithsimon (2008) documented, observed, and revisited Kayden et al. ‘s previously studied representative sample of 219 buildings with public plazas in assessing the correlation between design and use. He earlier planned to interview the developers, but as anticipated, all refused to allude to the reality of “elite behavior at odds with public norms” (p 336).

Director of urban design Jonathan Barnett whose tenure at the New York City planning department run from 1967 to 1971, was quoted to have written, “Spaces are often inhospitable, not because their designers were stupid but because of the owners of the buildings… deliberately sought an environment that encouraged people to admire the building briefly and then be on their way,” (Quoted by Smithson, 2008, p 336).

One staff joined, “Well, everything pointed in that direction, which is why we changed the regulations so many times. The client [i.e., the developer] wanted the space to be private, as private looking as possible, as private feeling as possible,” (p 336).

Designer Richard Roth from Emery Roth explained in the interview, “The plazas got bleaker and bleaker and bleaker – fewer people-oriented. […] Because, again, the owners of the buildings didn’t want a lot of people sitting in those spaces. Why do you never have seats in the lobby of an office building? Because they didn’t want people sitting there…” (quoted by Smithsimon, 2008, p 337).

Kayden et al. (2000) also assailed developers of the Paramount Plaza at 50th Street and Broadway for its two unused sunken sections as he wrote:

“… owners to the original developer of this Broadway office tower have faced an inherently problematic site condition at their full blockfront special permit plaza… two square holes punched into its north and south ends creating sunken spaces […] their pathology hard to discern,” (p 148).

Roth agreed with the observation narrating the obscene creations to have been detrimental to the commercial viability of the Paramount Building. “… they didn’t want anybody on the plaza […] It took them forever to rent those sunken areas.

On another note, another designer Saky Yakas opined that many of the designs compel people to think twice before using the privatized public space and that many are deceived that there were not for the public at all but private in nature. These were achieved through fencing, change of grade, how they were situated in relationship to the buildings of which use exudes exclusivity such as that for camera photograph background.

Developer Edward Sulzberger interviewed by the New York Times in 1969 was pointed out to believe that “One of the biggest problems of buildings’ security […] is loitering on the premises […] Builders therefore do not seek to make their plazas more comfortable to encourage passersby to spend time resting there,” making useless, barren and empty public space a design in itself (Smithsimon, 2008, p 339).

On the other hand, Jesse Clyde Nichol’s architects Edward Buehler Delk and George E. Kessler for the Country Club Plaza did well to spell out the desires of the owner with the human environment, and “sustainability” (long before it ever became the trend) in mind.

Today, the Country Club Plaza is considered the nation’s first suburban shopping center after its first buildings opened in 1923. The Plaza’s Spanish-style architecture, green spaces, and scenic location next to the Brush Creek not only respected the natural landscape but encouraged residents to nurture and cultivate plants that now draw many visitors as well as wealthy residents.

Ford (1999) pointed out that chief designer Delk was influenced immensely by Greek and Roman architecture. Both ancient cultures are long acknowledged as the perpetrators of “public” architecture. The immense acceptance of the Country Club District community and the Country Club Plaza proved J.C. Nichols’ method “planning for permanence” effective.

Nichols “develop whole residential neighborhoods that would attract an element of people who desired a better way of life, a nicer place to live and would be willing to work in order to keep it better,” (Worley, 1990, p106).

Another developer Melvyn Kaufman was also acknowledged to have produced people-friendly public spaces with large swinging benches, life-sized chess pieces, Wizard of Oz paths, gigantic clocks, and unconventional sci-fi aesthetics. He had been rated the highest at 3.5 from a scale of 1 to 5, with five as the highest in the study (Kayden et al., 2002).

Conclusion

There are certain procedures as well as elements in order to come up with an urban design in public spaces. As enumerated by Lang, these factors and practices are well in existence and observed.

All throughout, there is a clear understanding that architects and designers may be partially responsible for the aesthetic and physical attributes of public space in urban design.

However, the economic and political goals of such “creations” are fundamentally implemented in the end to meet that of the decision-makers or owners overshadowing whatever good the public may use of it. As may be observed in most establishments where a probably public space has been contracted, there is the limited enabling of the public to access such product design, visually.

At most, it becomes a piece of window display to attract probable customers or consumers for a trade of the day. While it attracts the public, it is not useful in such a way that no material or financial exchange transpired for it to become accessible in the real sense of the word. Such may be the case for a child’s playground in a private school bordered with a wire fence, a colorful playpen in a MacDonald’s, or even a free seat in a bus terminal.

There may be advantages of privatizing public spaces in order to meet the demands of a growing populace or even discerning urban tastes of cosmopolitan residents. These include accessibility to real designers with acceptable and unquestionable talent in producing visual art through the built environment, as well as funding for such projects.

However, as has been pointed out, the goal of the private, in this instance, the developer, owner, or investor, remains the most powerful force to be reckoned with. This is a bias against the marginalized and should be properly addressed by the known antagonists: the public officials.

Aside from the bias against the public, the aesthetic abilities of the designers or architects become limited, constrained, or non-existent, but the name simply as a symbolic marker for a project. This is a great injustice in many cases as designers, when guided properly or even when compromised, may produce human-magnetic products such as those done by the window or display artists.

Again, considering the elite sensibility, a crowd that could be produced in the process of attracting attention through architectural feats may be interpreted as mass, a mob, thereby, unable to afford sky-high costs of urban housing and accommodations that are offered by private developers given the right to provide space for the public.

Considering the housing crisis that besieged the many parts of the United States recently, the developers could be right. The must-have been right to delay selling all along by producing ugly public spaces.

The success of the suburban design of JC Nichols and Kaufman projects that used sprawling open spaces as public domain in his communities, provide a positive perspective that needs careful analysis and duplication among developers. Urban planners, architects, and designers, but most specifically, developers or owners, should start learning from the legacy of J.C. Nichols if they have not been aware of his people-oriented concept of success yet.

Reference

Boyer, M.C. (1993). The city of illusion: new York’s public places. In Knox, P., ed, The restless urban landscape. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: PrenticeHall.

Brain, David (1991). “Practical knowledge and occupational control: the professionalization of architecture in the United States.” Spciological Forum 6(2), pp 239-268.

Carr, S., Francis, M., Rivlin, L., and Stone, A. (1992). Public Space. Cambridge University Press.

Davis, Mike (1990). City of quartz: Excavating the future in Los Angeles. Verso.

Fordm, Susan Jezak (1999). “Biography of Edward Buehler Delk, (1885-1956), Architect; the chief architect of the Plaza.

Fyfe, N. and Bannister, J. (1998). “The eyes upon the street: Closed circuit television surveillance and the city.” In Images of the street: Planning, identity and control in public space, N. Fyfe (ed), Routledge. Pp 254-276

Gans, H. (2006) Jane Jacobs: Toward and understanding of “Death and Life of Great American Cities.” City and Community 5 (3), pp 213-215.

Goheen, Peter (1998) “Public space and the geography of the modern city.” Progress in Human Geography, Aug 1998; vol. 22: pp. 479 – 496.

Kärrholm, Mattias (2007). “The Materiality of Territorial Production: A Conceptual Discussion of Territoriality, Materiality, and the Everyday Life of Public Space.” Space and Culture, Nov 2007; vol. 10: pp. 437 – 453.

Kayden, J.S., the New York Department of City Planning, and Municipal Art Society (2002). Privately owned public space: the New York City Experience. John Wiley.

Lang, Jon (2005). Urban Design: A Typology of Procedures and Products. London: Architectural Press.

Langdon, Philip (2006). “Creating the Missing Hub: How Today’s Suburbs Build Town Centers.” PCJ #62, Spring.

Lofland, L.(1998). The public realm. New York: Aldine de Gruyters.

Mitchell, Don (2003). The right to the city: Social justice and the fight for public space. Guilford Press.

Smithsimon, Gregory (2008). “Dispersing the Crowd: Bonus Plazas and the Creation of Public Space.” Urban Affairs Review, Jan; vol. 43: pp. 325 – 351.

Wagner, Jacob (2003. “The Politics of Urban Design: The Center City Urban Renewal Project in Kansas City, Kansas.” Journal of Planning History, Nov 2003; vol. 2: pp. 331 – 355

Worley, William S. (1990) J.C. Nichols and the shaping of Kansas City : innovation in planned residential communities. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press.

Whyte, William (1988). City” Rediscovering the center. New York: Doubleday

Zukin, S. (1995). The cultures of cities. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Appendix