Abstract

Risk management is the key to successful projects. A risk management strategy gives a coherent approach for dealing with uncertainties that a project may face in a holistic manner. Uncertainty is unavoidable in projects because they have inherent variability of constraints and premises and involve diverse stakeholder interests. In this view, risk management may be construed as a means of navigating through the uncertainty to control the cost/impact and probability of occurrence of the identified risks. It enables organisations to identify, assess, and control risks to maximise project outcomes. A number of models, frameworks, and tools exist for understanding each step of the project lifecycle. Drawing on best practice principles and models, this report analyses the risk management strategy and processes for achieving organisational goals in the contexts of procurement and complex projects.

Introduction

Effective risk management is the hallmark of successful projects. It ensures the delivery of project results is within budget and on time to support the organisation’s strategic goals. Risk is inevitable in projects because of the variability of project constraints and stakeholder demands. The failure to manage risks effectively may negatively affect multiple project goals with implications for timelines (delay risk), cost, or quality (Alexander & Sheedy 2004). In this view, proactive actions by project managers could help identify risks and mitigate them based on best practice principles. Risk management gained much interest in the late 2000s in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. It is now considered a critical process in all major projects and involves a range of complex tools for risk identification, such as risk registers and SWOT analysis. The aim of this report is to analyse the concept of project risk, risk measurement and ranking, and risk management strategy, and best practices in risk management.

The Concept of Project Risk

The risk may be conceptualised as an uncertain event that could potentially affect project goals (Holton 2004). It can be contrasted with ‘opportunity’, which may be construed as the desired positive event. Historically, risk has been associated with the uncertainty or fear that surrounds personal decisions. The type of decision or choice made relies on the individual’s personality, i.e., risk averseness or risk-taking behaviour. In business, the concept of risk takes a different form; the risk could be interpreted as a threat or an opportunity for growth.

Although multiple perspectives exist on the concept of risk, they converge on the view that risk is linked to uncertainty towards a potential threat. Holton (2004) defines risk as a state of affairs connected with the possibility of a “deviation from a desired outcome” of a project (p. 23). The desired outcomes could be the budgeted cost, delivery time, and quality (Holton 2004). On his part, Murray-Webster (2010) considers risk as an uncertain event with a positive or negative impact on project goals when it occurs. A good example is the supply chain delay that leads to transportation risk. Therefore, a risk could be conceptualised in two ways: first as an unwanted probability event, which hinders the attainment of the performance targets of a project, and second as the cause of the undesirable event. A risk is a probability event that depends on exposure. Thus, risk assessment takes into account the values of the outcomes (expectation value) and their respective probabilities.

It is clear that uncertainty and exposure are critical components of risk. Uncertainty, defined loosely, is a state of being unsure of a proposition’s outcome (Hubbard 2009). An example of uncertainty is the rolling a six-sided dice in a casino where obtaining a four indicates a win is an uncertain task. The chance of winning is a sixth. However, if the one is uncertain of the number of sides of the dice, then the probability of winning or the risk of loss may not be known. Uncertainty arises when cannot perceive the outcomes or proposition. Therefore, in uncertainty situations, probability has limited usefulness.

On the other hand, exposure is the self-consciousness experienced when exposed to a proposition. In most cases, the perceived exposure relates to relevant events as opposed to immaterial ones (Hubbard 2009). Importantly, uncertainty does not affect exposure, which means that being uncertain of an event does not mean the absence of exposure. For example, exposure may arise when a firm incurs financial loss due to the lack of a risk management plan. In this case, the firm is certain of possible loss whenever exposed to an identified event.

In this view, the risk is the exposure to an event that an individual is uncertain of currently (Alexander & Sheedy 2004). A project introduces new changes to an organisation, which lead to uncertainty. Exposure to uncertainty creates risk. An organisation brings together risk-takers, including investors, staff, and stakeholders. The identification, assessment, and mitigation of risks through an effective risk management plan are essential for project success. The process entails decision-making and evaluation of choices based on experience, risk attitude, and resources available. For example, public and health institutions often adopt a risk-averse attitude due to the view that risks lead to losses. On the other hand, venture capitalists and entrepreneurs are driven by a risk-seeking attitude, believing that opportunities exist in risky contexts.

Risk Measurement and Ranking

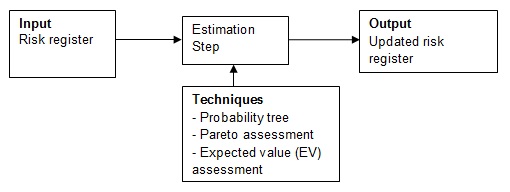

The measurement and ranking of project risk constitute a key step in the risk management process. After the risk has been identified, a qualitative and quantitative analysis is done to evaluate and subsequently manage the risk. Risk assessment entails risk estimation and risk evaluation steps. Risk estimates can use the qualitative or quantitative approach to rank or express the risk numerically (Dorfman 2007). The aim of estimating risks is to establish a ranking of risks grounded on their cost impact. Cliland (2004) writes that to prioritise risks, and understanding of the “probability of each threat and opportunity”, effect on project goals, and expected time of occurrence is required (p. 81). The assessment step may involve techniques such as constructing a probability tree, Pareto assessment, and expected value assessment. The project manager may use “risk monetary value, probability, or its impact” to rank the risk (Cliland 2004, p. 83). The chosen risk metric depends on the firm’s risk management strategy. The estimation step of the risk assessment process is summarised in figure 1 below.

Monetary-based ranking of risks using the EV method can be achieved using the following formula: RMV = P x RIV, where RMV is the risk monetary value, P is the probability, and RIV represents the risk impact value. The risk probability may be computed based on expert advice or using the Delphi method (Gallati 2003). The aim is to obtain a consensus risk probability that could be used to rank the identified risks. The Pareto method could also be used to select a risk with the most significant impact value. An example of project risk ranking using the risk monetary value is shown in table 1 below.

Table 1: Risk Monetary Value.

The RMV method facilitates the comparison and prioritisation of risks. The ranking of risks is founded on a project risk management strategy of a firm. In this case, the RMV varies depending on the risk effect and the likelihood that range between low and high in the probability and impact dimensions. This matrix gives a risk profile for a given project. An example of a risk profile is given in Table 2 below. It is evident that risks 7 and 8 require urgent action because their RMV is high.

Table 2: An Example of a Project Risk Profile.

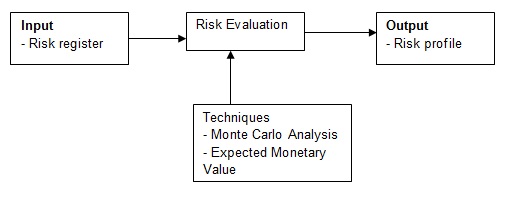

The risk evaluation step entails determining the “overall risk exposure” based on the net impact of “threats and opportunities” on the project (Spedding & Rose 2011, p. 58). The aim is to ensure that the project risk is within the thresholds prescribed by the organisation’s risk policy. The evaluation step is summarised in figure 2 below.

The evaluation can be done using the monetary value approach. The expected monetary value is the product of risk and its likelihood of happening (Spedding & Rose 2011). The sum of the values gives the expected monetary value of a project. An example of an evaluated risk monetary value is shown in table 3 below. The risks may cost the project $141,000. The organisation can choose to proceed or terminate the project based on this value.

Project Risk Management Strategy

Mitigating risks in complex or international projects requires a risk management strategy. This iterative process entails sequential steps for managing risks throughout the project lifecycle in line with the set strategic objectives. It gives a coherent approach for “identifying, assessing, and managing” risk (Smith & Fischbachera 2009, p. 7). For an international project, the five steps of the risk management model may include risk identification, assessment, mitigation planning, implementation, and communication.

Risk Identification

It entails a structured process of identifying high probability risks or events that are threats to the project. A project manager may use checklists to identify risks. The potential risks depend on the nature of the project including its strategic goals, activities, and constraints, among others (Cliland 2004). Besides risk checklists, risk categories (group technique), questionnaire, and constraint analysis may be used to identify the risk sources. Examples of risk categories include financial, contractual, cost, people, technical, political, etc. For instance, people risks may be skill deficits in the project.

Hillson (2003) utilises the work breakdown structure (WBS) model to organise potential risks into distinct categories. The resultant risk breakdown structure is summarised in a table, which essentially lists the potential risks inherent in a complex project. The approach supports a clear understanding of risks that exist within the WBS framework. The only downside of this model relates to its restrictiveness; thus, it cannot identify unknown risks. The aim of project risk identification is to generate a clear analysis of the “cause, event, and effect” of each risk (Hillson 2003, p. 87). A risk cause is the source of risk while a risk event is a threat or opportunity resulting from an identified risk. An example could be poor supply chains (cause) that affect inventory management (event). A risk effect is an impact that the risk may have on the project’s goals.

Risk Evaluation

The identified risks are evaluated to determine their likelihood of happening and impact on project goals. Risks vary in terms of probability and impact. Certain risks are more likely to occur than others are. Additionally, the severity of the loss differs significantly between risks. Therefore, a project team may use risk evaluation criteria to narrow down on a few high-probability risks that have a significant effect on project performance. For example, if the risks that raise costs by 4 per cent are considered high-impact risks, the team’s mitigation plan should focus on these risks to reduce the impact. An example of a risk evaluation matrix is shown in table 2 above. From the table, it is clear that risks 7 and 8 have the highest likelihood of occurring and the greatest effect on the project.

Based on the RMV framework, a positive correlation exists between complex projects and risk severity (Dorfman 2007). Therefore, a multisite international project is a high-risk endeavour due to the massive resource requirements. The project team will need to allocate resources appropriately to achieve the set objectives. Additionally, complex technology e.g., aircraft parts, will be required for an international aviation project, raising the potential for unexpected challenges. Risk evaluation for complex projects should involve brainstorming sessions or workshops to assess each risk event to establish its probability of happening and cost or effect on the project. The probability and cost may be low, medium, or high depending on the nature of the risk. Therefore, cost and likelihood rankings determine the risk management strategy to be used.

Evaluating a Procurement Risk

Delays in the delivery of project equipment constitute a procurement risk. An analysis of the vendor or supplier would help determine the likelihood and potential effect of the procurement delays. A formal risk assessment would unearth this risk, especially in complex projects. However, few project managers use this approach. A study by Parker and Mobey (2004) found that project managers rarely conduct a “structured analysis of procurement risks” due to a limited comprehension of the assessment tools (p. 27). In addition, some managers were risk-averse or reactive, limiting the success of complex projects.

In big projects, developing a list of events considered risky and monitoring them throughout the project lifecycle may alleviate risks. A formal risk assessment process could also help evaluate the risk profile at different stages of the project. Statistical models may be employed to assess risks, especially in projects involving many variables or combinations. An example is the Monte Carlo model, which is a useful method for evaluating risks in highly complex projects. It simulates the range of outcomes through a trial and error method involving various “combinations of risks based on their likelihood” (Horwitz 2009, p. 77). The model gives the project team the range of possible outcomes based on different likelihood/impact combinations. For example, the simulation may indicate that there is a 10% likelihood that procured equipment will be delivered late and its impact on the project.

Risk Planning

Risk planning entails developing reactionary management actions to eliminate threats and capitalise on opportunities. The threat responses may include avoidance measures, e.g., reducing the likelihood or effect, falling back to minimise the impact, or transferring the risk (Tusler 2006). The organisation can also choose to share or accept the risks. On the other hand, opportunity responses may include exploitation, rejection, or enhancement of the risk. Besides the risk response planning, a firm may use cost-benefit analysis or decision tree to devise appropriate responses to risk-related threats or opportunities.

Implementation of the Risk Plan

A risk management strategy should give a risk response plan to track and control risks at different stages. An efficient implementation process requires that the roles of the risk response team be identified. The risk owner is the firm that tracks and controls allocated risks to enhance the returns (Tusler 2006). On the other hand, the risk auctioneer supports the risk owner in implementing the risk plan.

Risk Communication

A clear communication management strategy is required to pass information related to the risks to stakeholders. The information could be communicated in terms of highlight reports, checkpoint reports, or lessons learned reports. The information could be communicated in meetings bringing together project stakeholders from different countries. For example, an international conference could be held to communicate an aviation project risk to stakeholders. An iterative process of tracking and controlling risks should be implemented using tools like variance analysis and reserve analysis to identify appropriate corrective actions.

Best Practices in Risk Management

In practice, the project manager selects the risk mitigation strategies. As the risk owner, he or she decides on the risks to minimise based on their impact and likelihood of occurrence. Another approach involves identifying the sources of the risks (root cause analysis) and applying corrective actions to reduce the probability and likelihood of occurrence of more than one risk. Subsequently, the risks could be rated based on the mitigation costs to minimise their effects (Benta, Podean & Mircean 2011). The aim is to reduce the aggregate project risk, i.e., the total value of all risks.

Different strategies are used to minimise the quantified project risk. The first method is risk avoidance. In this case, the project manager avoids activities that would ultimately cause risk. For example, the manager could choose low risk activities to reduce the overall impact. However, this option may not be economically viable, especially for large projects where profitability growth requires risk taking. The second approach is reducing the adverse effects of the risk or its impact on project goals, which may include delays, costs, or diminished quality (Benta, Podean & Mircean 2011). The risk manager may opt to transfer a high-probability risk to a third party to minimise the risk impact. For example, insuring equipment in transit could reduce the risk impact related to delays, which helps transfer the risk.

It is important to note that the aim of risk management is not to remove all risks, but to reduce the likelihood of occurrence and impact on project goals. In practice, the project manager develops a detailed report of mitigation actions for all identified risks. The report contains the costs, roles, due dates, and outcomes of the mitigation actions (Smallman 2009). The mitigations should aim to minimise high-impact/probability risks within acceptable costs. A risk analysis framework helps visualise the mitigation costs and the impact of risks in the absence of mitigation (Smallman 2009). Thus, the project manager should rank the mitigation actions based on cost and effect to determine when they should be implemented and by whom. The implementation of the measures should involve the entire project team.

Conclusion

Risk management in a project entails identifying, monitoring, and controlling risks throughout the project’s lifecycle. It involves various models for risk identification, evaluation, and mitigation to minimise the likelihood of occurrence and impact on project goals. Complex high-risk projects require effective risk management strategy to ensure that the project meets its objectives.

References

Alexander, C & Sheedy, E 2004, The Professional Risk Manager’s Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide to Current Theory and Best Practices, PRMIA Publications, Wilmington, DE.

Benta, D, Podean, M & Mircean, C 2011, ‘On Best Practices for Risk Management in Complex Projects’, Informatica Economica, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 142-151.

Cliland, D 2004, Field Guide to Project Management, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, New York.

Dorfman, M 2007, Introduction to Risk Management and Insurance, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Gallati, R 2003, Risk management and capital adequacy, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Hillson, D 2003, ‘Using a Risk Breakdown Structure in Project Management’, Journal of Facilities Management, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 85–97.

Holton, G 2004, ‘Perspectives: Defining Risk’, Financial Analysis Journal, vol. 60, no. 6, pp. 19-25.

Horwitz, R 2009, Hedge fund risk fundamentals: solving the risk management and transparency challenge, Bloomberg Press, Princeton, NJ.

Hubbard, D 2009, The Failure of Risk Management: Why it’s Broken and How to Fix it, John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Murray-Webster, R 2010, Management of Risk: guidance for Practitioners, Office of Government Commerce, London.

Parker, D & Mobey, A 2004, ‘Action Research to Explore Perceptions of Risk in Project Management’, International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 18–32.

Smallman, C 2009, ‘Knowledge Management as Risk Management: A Need for Open Governance?’, Risk Management, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 7-20.

Smith, D & Fischbachera, S 2009, ‘The changing nature of risk and risk management: The challenge of borders, uncertainty and resilience’, Risk Management, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–12.

Spedding, L & Rose, A 2011, Business Risk Management Handbook, London, Elsevier.

Tusler, R 2006, An Overview of Project Risk Management, Web.