Introduction

Families in ancient Rome were often cramped and typically small. Some Roman homes were quite dark and necessitated the installation of windows. The Romans used divider paintings to open up and brighten their environments, making them appear larger. They made use of frescoes (Dardenay, 2018). A fresco is innovated by adding around one to three layers of mortar, a combination of sand and lime combined with powdered marble. While the mortar is still wet, colors are put appropriately to form an artistic effect. Most old Roman frescoes have been uncovered at Pompeii and encompass settlements because of Mount Vesuvius’ safeguarding impact.

The divider painting styles have enabled craftsmanship antiquarians to recognize various moments of interior enlivening in the years preceding the Vesuvius eruption in 79 AD, which both damaged the city and protected the works of art, as well as complicated modifications in Roman craftsmanship (Bragantini, 2019). Emotive subjects are revisited throughout the evolution of styles. The canvases also reveal a lot about the luxury and unorthodox tastes of the period. Art historians have identified four fresco divider compositions based on discovering wall paintings. The four classes are depicted in general and by specified distinguishing norms.

The indigenous styles of Romans that were evolved are intricate, decorative, inclusive, and architectural. The techniques are unique; however, each type contains the characteristics of the preceding style. Individual pieces of art were made before Mount Vesuvius exploded. The initial two kinds, the inclusion, and architecture, were associated with the Hellenistic Greek divider paintings. At the same time, the latter two (fancy and mind-boggling) were associated with the Imperial period. Roman divider compositions are great showpieces seen in private homes around Rome and the Italian countryside.

Incrustation Painting Style

The Incrustation style, also known as stonework style, was typically discernible from 200 BC to 80 BC. The marble-like effect was achieved via plaster moldings that raised the divider’s voids. Other replicated components, such as discs in vertical lines, ‘wooden’ radiates in yellow, and ‘columns’ and moldings in white, were seen as lucky traits, as was the use of dynamic shading. Less wealthy people primarily used pink, purple, and yellow variations.

The incrustation plan was a multiplication discovered in the eastern Ptolemaic castles, where the dividers were trimmed with genuine marbles and stones. It also addresses the development of Hellenistic human progress during this period, as Rome drew in with and vanquished neighboring Greek and Hellenistic powers (Brain, 2019). Greek compositions have also been passed down over many centuries. This method Split the divider into several different colored patterns, substituting the exceedingly expensive cut stone. The Incrustation style was occasionally used in conjunction with other techniques to embellish lower partitions that were not as visible as the higher ones. Examples of houses that used this model are Herculaneum’s Samnite House, House of Sallust, and Pompeii’s House of Faun.

Architecture Painting Style

The first century BC was dominated by the second technique, architectural, or ‘illusionism style ‘ divisions covered structural nuances and Trompe-Lil (eye trick) syntheses. Parts of this style are immediately evocative of the First Style, although these are gradually, replaced component by component..The Romans typically utilized this approach, which consisted of underlining pieces to make them appear three-dimensional – sections, for example, isolating the dividing space into zones. The use of marble blocks was continued in the next plan. The squares were typically set at the divider’s foundation, and the accurate picture was created on level mortar.

In any event, deceptions of anecdotal scenarios were shown in several works of art. Painters hoped to convey that the viewer was peering out the window at the scene they were depicting. They also added things usually found, such as jars and bookshelves, and items they wished removed from the partition (Bragantini, 2019). This strategy was designed to make viewers feel that the events depicted in the artwork were happening right in front of them. It is distinguished by using relative views (rather than direct points of view, as this style, like the Renaissance, employs numerical standards and logical extents) to generate Trompe-Lil in divider compositions.

Painted building details, such as Ionic segments or organizing stages, pushed the picture plane further and deeper into the divider. These wall arrangements alleviated the claustrophobic situation of Roman houses’ restricted, austere offices. Around 90 BC, pictures and scenes were introduced into the primary style, and they rose to famous from 70 BC onwards, with illusionistic. The goal of the enrichment was to generate the most profound impact possible. Impersonations of images first appeared in the top section, then in the foundations of scenes that served as a performance center for fantastic stories, dramatic veils, or ornaments circa 50 BC.

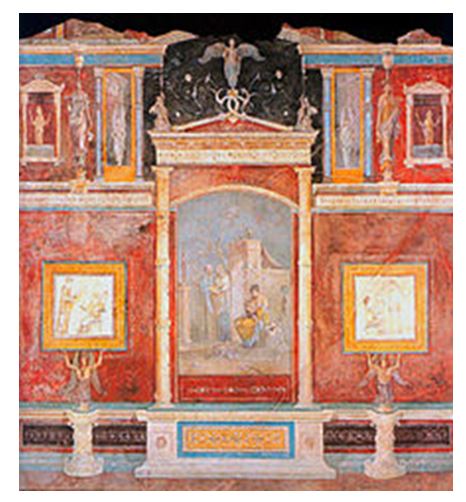

Throughout Augustus’ reign, the style evolved. Bogus design components provided up a world of inventive options. A phase set-roused structure was created, with one massive center scene flanked by two smaller ones (Brain, 2019). The illusionistic pattern remained in this form, with divisions “separated” by painted technical pieces or landscapes. The scene elements gradually took possession of the whole partition with no outlining method, giving the audience the impression that the subject in question was to stare out of a room into a natural environment.

The more mature Second technique was essentially the inverse of the First Style. Rather than encasing and sustaining the dividers, the idea was to destroy them to reveal new perspectives on nature and the rest of the world. The use of the aeronautical point of view, which softened the picture of things further away, contributed significantly to the depth of the adult second style. As a result, the foreground is relatively precise, even though the scenery is slightly tangled with purple, blue, and dim. The Dionysian mystery frame at the Villa of the Mysteries is one of the most notable and unmistakable Second Style figures. This model is geared towards the Dionysian Cult, primarily women. It was fashionable from the 40s BC forward; however, it later blurred. The compositional artwork of the Villa Boscoreale at Boscoreale is one example.

Ornamental Painting Style

As a reaction to the heaviness of the preceding period, the third technique, or opulent style, emerged circa 20–10 BC. It considers more allegorical and different decoration, with a growing general mindset, and frequently demonstrates tremendous refinement in execution. This style is well-known for its straightforward beauty (Dardenay, 2018). Its primary distinguishing feature was a move away from illusionistic techniques, but they (along with figural portrayal) eventually returned to this style. It adhered to the highlight’s rigorous evenness requirements, separating the divider between three even and three to five vertical zones.

In this design, the wall space is colored, with no adornment. When there were designs, they were mainly plain, basic sketches or scenes, such as a candelabrum or fluted. Images of semi-fantastical or delicate birds emerged in the background. Following Augustus’ defeat of Egyptian Cleopatra’s annexation in 30 BC, plants and Egyptian animals were frequently depicted in Roman art as part of the Egyptian mania.

These paintings were embellished with immaculate straight dreams, usually in monochrome, which replaced the three-dimensional cosmos of the Second Style. Canvases similar to Cubiculum 15 of the Villa of Agrip a Postumusin Boscotrecase can also be found in this style (Bragantini, 2018). These have a delicate edge over a clean, monochromatic basis, with only a minor subject in the center, like a more miniature than expected floating landscape. Black, red, and yellow were still used throughout this period, but green and blue were more prevalent than previous designs. It was discovered in Rome until the year 40 AD and in Pompeii until the year 60 AD.

Intricate Painting Style

The Fourth technique in Roman divider painting is less ornate than its precursor and is regarded as a Baroque response to the decorative style eccentricities. The style, on the other hand, was more contemporary. It incorporates large-scale account painting and all-encompassing sceneries while retaining the characteristics of second and first styles. A material-like angle prevailed throughout the Julio-Claudine period, and rings appear to connect all of the elements on the divider. Colors do brighten up, and they are used essentially in depictions of unbelievable circumstances, settings, and other symbols.

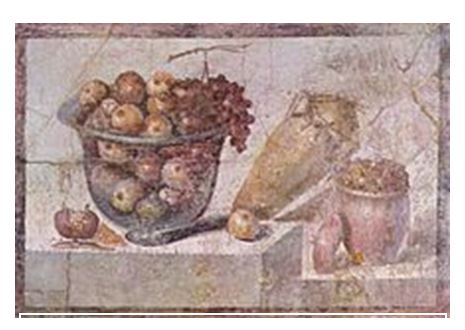

Unpredictable pieces of art looked to be more occupied and necessitated the completion of the entire divider. A mosaic of highlighted pictures was often used to create the overall effect of the partitions. The most limited zones of these dividers were often fashioned of the First Style. On the sections, boards with floral designs were also employed. The Ixion Room in Pompeii’s House of the Vettii is an obvious example of the Fourth Style (Dardenay, 2018). One of the most significant achievements of the Fourth Style is the improvement of still existence via the use of severe Light and space. The intricate style was not visualized again until the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries when English and Dutch decoration became more prevalent.

Conclusion

Over time, Roman wall creative masterpieces evolved into several styles that are still observed by viewers now. Roman walls were covered with various murals in the first century BC. The type of these artistic creations evolved from practical to impressionist. Folklore, scenery, and various leisure activities serve as sources of inspiration (Brain, 2019). Frescoes are commonly built on mortar with colors put to them while drying. Today’s discoveries were made in and around the Bay of Naples, where Mount Vesuvius released ash. The works of art depicted life in this place before the massive emissions that destroyed a substantial portion of the field, as did the urban settlements of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

In Roman households, divider artistic items were occasionally a mash-up of numerous types. It started as a housekeeper’s helper. Famous guests would follow the expensive, bright decorations, while slaves and laborers would remain in the lonely entrances. Second, the frescoes served as a social bearing throughout the neighborhood (Dardenay, 2018). The number and type of frescoes revealed the family’s wealth and social objectives. As done almost 2,000 years ago, the specialty of frescoes is both imaginatively and fundamentally important.

References

Bragantini, I. (2019). Towards a cultural biography of Roman painting. Journal of Roman Archaeology, 32, 129-147. Web.

Brain, C. (2019). Painting by Numbers: A Quantitative Approach to Roman Art. Theoretical Roman Archaeology Journal, 2(1), 10. Web.

Dardenay, A. (2018). Roman wall-painting in southern Gaul (Gallia Narbonensis and Gallia Aquitania). Journal of Roman Archaeology, 31, 53-89. Web.