Introduction

The routine activity theory was developed by Felson and Cohen in the 1970s and created a subfield within the crime opportunity theory. What makes routine activity theory stand out is the fact that the researchers were among the first criminologists to shift the focus from the criminal to the event of a crime itself. Felson and Cohen argued that the personality of an offender mattered only to a certain extent. The police and other authorities could not afford to analyze every single offender’s pathological inclinations. Examining crime as an event and not just an offender’s conscious action requires studying the environment that might have predisposed it. What Felson and Cohen deemed more effective and sustainable is to adopt a large scale approach and look at trends and tendencies in crime within a constrained period. This research paper explores the routine activity theory in detail and provides an analysis of Washington, District of Columbia, within its framework.

Problem Statement

Crime prevention is extremely challenging because it implies adopting a proactive, not reactive approach. Preventing crime means calculating the probability of it happening and pinpointing the possible location. The process is complicated because it deals not only with the mechanics of action but also with complex psychological concepts such as motivation. So far, criminology has seen several frameworks that dissect crime into key aspects and seek to understand their relationships and interactions. Eck and Weisburd put forward a triangle model that includes offender, target, and guardian; other models encompass not individuals but abstract notions such as desire, opportunity, and target (30). The logical question arises as to exactly what motivates people to partake in illegal activities.

Previously, among factors that drive people to commit crimes, researchers pointed out socioeconomic factors such as poverty, unemployment, and lack of education. That manner of thinking gave rise to the so-called dispositional theories in criminology. Primarily, they sought to answer the question of criminality by pinpointing a certain causal mechanism. Building on this idea, it would be safe to assume that it is the poverty-stricken counties and cities in the United States that suffer the most from crime. The example of Washington, DC, counters this hypothesis: despite being the fifth wealthiest state in the US, its crime rate is 102% higher than the national average (“Washington, DC Crime”). This evidence makes one wonder whether situational theories such as routine activity theory authored by Felson and Cohen could explain this paradox. Situational theories accept criminal inclination as a given and insist that the various sociological factors might push some individuals to break the law but not strictly necessary for it to occur.

Overall Framework and Assumptions

In their most important paper, “Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach,” Felson and Cohen claim that it is the changes in routine activities that determine the possibility of crime. The paper defines crime as “direct-contact predatory violations,” or illegal acts in which “someone definitely or intentionally takes or damages the person or property of the other (Felson and Cohen 589).” Further, Felson and Cohen refer to the oft-cited triangle of crime that consists of three key elements: offenders, targets, and guardians. The researchers provide their own take on the model and claim that crime happens on the premise that there are motivated offenders, suitable targets, and absent guardians. However, as Felson and Cohen reasonably point out, the numerical value of potential offenders and targets at a particular place is not enough to understand the actual likelihood of a criminal activity taking place.

For this reason, the researchers make it a point to add to more elements to the model: time and space. They state that the highest likelihood of crime is achieved not only due to the presence of all the three aforementioned elements but also due to the convergence of time and space (Felson and Cohen 560). Any space, in this case, is treated not as a static unit of territory but as a symbiotic organization. Felson and Cohen draw on the ecological theory of crime and outline the three most important temporal aspects in the existence of such spaces that are often neglected in practical criminology.

Firstly, there is a rhythm that indicates the regular periodicity with which activities occur, for instance, events that attract large numbers of people. Then, there is a tempo or the number of activities occurring per the chosen unit of time. Lastly, there is a timing that determines how an offender’s activities are coordinated with a victim’s activities. Simply put, for crime to occur, an offender needs not only to be motivated and have identified a potential target, but he or she needs to be in the right place and at the right time. Within this framework, illegal acts are treated as routine activities that share many characteristics of and interdependent with other routine activities in the area.

Felson and Cohen provide an example from an earlier study by Roncek and Choldin and Roncek that confirms their hypothesis. The study shows that the number of individual households on a block predicts the likelihood of crime and its rate, even when controlled for race, ethnicity, income, and other factors (Felson and Cohen 595). Within the proposed model, individual households were suitable targets as, during the day, they would be left without proper guardianship. The proximity of potential offenders and their knowledge of victims’ work rhythm would create a perfect opportunity for committing a crime. Felson and Cohen conclude that the crime rate has the potential of being dramatically reduced if even one element of the triangle model is removed or improved.

Literature Review

Now that the rationale behind the routine activity theory is clarified, the question arises as to how consistent real-life evidence is with its key postulates. Weisburd et al. refer to the assumption that particular characteristics of spaces such as the efficiency of guardianship, the presence of motivated offenders, and the vulnerability of suitable targets influence the likelihood of crime (30). Therefore, as the researchers assume, the crime rate among certain demographics will be higher in places where the said demographics are concentrated. Weisburd et al. provide a clear example: they suppose that young people prefer very specific types of activities, which determines their activity spaces (30). Indeed, parks, malls, and cinema theaters attract great numbers of juveniles, and many businesses even make it a point to gain more young customers.

Weisburd et al. refer to earlier studies that have found that juvenile delinquency shows a strong correlation with time spent participating in unstructured activities with peers in the absence of guardians (31). Their own study has demonstrated that only specific age-relevant locations show surges in juvenile delinquency. 30.7% of juvenile criminal activities were taking place in schools and youth centers, and 38.9% – at shops, malls, and restaurants (Weisburd et al. 30). As evident by arrest incidents, the aforementioned places were turning into hot spots. As opposed to them, bars and taverns where young people are typically not allowed showed only a meager fraction of percent in crime activity shares. Weisburd et al. interpret the data and conclude that the more juveniles concentrate in one place, the more potential offenders and victims there might be, which is consistent with the routine activity theory. This social dynamic explains why juveniles typically choose other juveniles as their targets.

From the cited evidence, it is clear how some places provide an extra opportunity for victimizing other people in the absence of strong guardianship. The logical question arises as to routine activity theory is as efficient in reducing crime as it is in singling out specific problematic places. In applied criminology, Felson and Cohen’s theory is widely used for the practice called hot spots policing. Hot spots policing is problem-oriented: it rejects the generalized approach and focuses on confined areas that are more prone to causing problems. Such an approach is seen as more sustainable and productive as it not only solves the problem for the respective communities but also prevents crime from spreading.

In their meta-analysis of the literature on the topic, Weisburd et al. describe the first hotspots study conducted in Minneapolis in 1995. Police officers were not given any specific instructions as to what they needed to do once they had arrived at a problematic neighborhood. It turned out that the mere presence of the police resulted in a reduction of crime and disorder. The researchers calculated the ideal time that police officers need to spend on the spot to prevent crime from occurring and concluded that it would take from 14 to 15 minutes (Weisburd et al. 39). Staying any longer than that did not provide additional benefits.

A more recent study revealed that even if police officers monitor a hotspot unarmed and with few arrest powers, offenders might still be deterred from following through with their plans. Ariel et al. assumed that the police no longer needed to depend on hard power and control criminals with the immediate threat of arrest solely (285). Instead, the authors decided to prove that signals of social control, a less resource-consuming means, might be sustainable. The findings matched the hypothesis as the crime rate in 34 hotspots in England and Wales decreased.

Discussion of the Theory

As with many other theoretical approaches, routine activity theory does not allow for easy, straightforward interpretation, nor does it offer “one-size-fits-all” solutions. The key takeaway from the original seminal paper, “criminal acts require the convergence in space and time of likely offenders, suitable targets and the absence of capable guardians,” is far from self-subsistent. Depending on the area of application, the theory may be mobilized in various ways. For instance, in their initial paper, the researchers defined the scope of the application as only including direct-contact crimes (Felson and Cohen 589). However, since the 1970s, a great share of criminal activities has relocated to the Internet, which calls for some theoretical adjustments. Aside from that, since the initial publication, Felson and Cohen have kept working on their framework, which makes it far from static. It is up to practitioners to choose which aspects of the ever-changing and evolving theory they see fit in their concrete situation.

Despite the wide scope of application and its general recognition in the criminology field, the routine activity theory has also faced up to critical arguments. The principal criticism of the framework addressed its efficacy, morality, and political legitimacy. Some of its ideas were interpreted as essentially blaming the victim. In relation to its efficacy, the opponents of the theory claim that even when properly applied, its methods do not have much of a positive effect. In particular, what is seen as a reduction in crime is effectively a displacement of time, target, tools, resources, or the form of the mediated crime.

Some other postulates of the theory that have been widely criticized are the concepts of crime rationality and opportunity. Eck and Weisburd point out that the rational element is often absent in the most violent crimes and that the routine activity theory chooses to ignore the emotional side of criminal activities (14). As for the opportunity aspect, Eck and Weisburd state that it is not exactly possible to tell whether a certain place can dramatically change a person’s capacity and readiness to commit the crime (14). Some places might as well be poles of attraction for crimes that would have taken place anyway.

Lastly, the moral grounds of the theory have also been subject to scrutiny. Some criminologists point out that by focusing on the “place” corner of the crime triangle, the routine activity theory ignores the offender and their motivation. Namely, the approach fails to provide meaningful answers to such questions as to what or who motivated offenders and what common characteristics they have. Besides, it is quite clear that even when put in the same place with a high probability of criminal activity as per professional assessment, some people will be more or less likely to misconduct (Eck and Weisburd 27). Drawing on these points, one may argue that in a way, the routine activity theory blames the victim for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. It is hard to say how efficient victim-blaming is for crime prevention.

Historical Background

As mentioned earlier, the routine activity theory was authored by Marcus Felson and Lawrence E. Cohen. Currently, Dr. Marcus Felson is a professor at Texas State University; his areas of expertise include routine activities, environmental criminology, and crime analysis. His biography page on the university’s official website indicates that Felson has Bachelor’s, Masters, and Doctorate degrees in sociology. To this day, Felson seeks to explain crime in tangible terms and find ways to reduce it through understanding its context (“Dr. Marcus Felson”). The researcher’s works have found use in investigating juvenile street gangs, co-offending, organized crime, and outdoor drug sales.

Lawrence E. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of California at Davis. His areas of interest and scientific inquiry are criminology and juvenile delinquency. Cohen’s most well-known contribution to criminology is the theory of routine activity that he formulated with Marcus Felson in the late 1970s (Eck and Weisburd 15). Among other subjects, Cohen has been studying crime development and its distribution in the United States after the Second World War.

Researching the historical context in which Felson and Cohen were developing their theory is key to understanding why it filled or even created an untapped niche in criminology and gained so much traction. The criminologists set out on their research two decades after the Second World War. Traditional criminology was projecting a reduction in crime due to the increasing wealth and expanding social welfare in Western countries as they were recovering from the war. Yet, since the 1940s, the crime rate in the United States had only soared, which was incomprehensible.

Felson and Cohen put forward a hypothesis that was quite sensational in the criminology world. The researchers rejected the idea that individuals committed crimes out of dire need and explained that people were driven by self-interest that went beyond necessities. Within their theory, a recent surge in crime was attributed to the growing opportunities, not growing needs. In their seminal article, “Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach,” Cohen and Felson shed light on the confusing social paradox. The authors explained that socioeconomic factors such as poverty, lack of education, and unemployment that had traditionally been seen as predisposing to a crime might have had a less prominent role.

Cohen and Felson claimed that it was critical to focus on changes in structural patterns of individuals’ daily activity and pose a question of how these changes were providing or not providing criminal opportunities. For instance, after the Second World War, more offenders could afford to buy a car which allowed for faster and easier navigation. Hence, criminals did not go out on a limb to commit a crime: they merely took advantage of their own and others’ routine activities and the environment.

It is important to note that Cohen and Felson’s framework did not fall on deaf ears because the entire field has already been undergoing a big change. The early 1970s has been marked with critical criminology coming into prominence. By the time Cohen and Felson put forward their theory, critical criminology approaches had already consistently pushed the boundaries of the field. Critical criminology was rejecting the superficial, “cosmetic” changes to the justice system and was inquiring whether the crime could be investigated alternatively (DeKeseredy and Dragiewicz 6). Cohen and Felson proposed a simple but rigorous way of reducing crime, which made a difference for the entire field.

Deanwood, Washington, DC

The location that has been chosen for the analysis is Deanwood, Washington, District of Columbia. The selected neighborhood is located in the Northeastern part of the city. It borders Eastern Avenue to the northeast, Division Avenue to the southeast, Kenilworth Avenue to the northwest, and Nannie Helen Burroughs Avenue to the south. Deanwood makes part of Northeast’s oldest neighborhoods: the majority of its housing stock was developed back in the early 20th century (“Deanwood Demographics”). Deanwood consists of low-density, small wooden and brick homes with dense forestation in between, which gives it a unique character. Less than 4% of the housing units (1,076) were built in the 2010s. The neighborhood’s infrastructure is limited to three metro stations (Deanwood, Benning Road, and Minnesota Avenue) and three major bus routes.

Former farmland worked by enslaved Black people, to this day, Deanwood remains a Black-majority neighborhood. 94.53% of Deanwood’s population is Black, 1.16% are White, and 0.27% are Asian (“Deanwood Demographics”). Almost two-thirds of Deanwood’s population (44,141 out 62,565) live below the poverty level; the median household income is $36,398 (“Deanwood Demographics”). The Northeast neighborhood does not see much mobility in terms of the inflow of new residents. Only 91 people residing in the area have moved from abroad, and 1,895 have relocated from a different state. 57% of Deanwood’s workforce is hired by private companies, and 25% work for the government (“Deanwood Demographics”). The Northeast neighborhood was ranked “F” (very bad) for its schools, safety, and employment opportunities.

The neighborhood of Deanwood is infamously known for its high crime rate. The total number of crime incidents per year is 8,760, while the average of the entire city is 5,211, and the average of the country is 2,580 per every 100,000 people (“Deanwood, Washington, DC Crime”). The two categories of crime that Deanwood suffers from the most are violent crimes (2,663 per 100,000 as compared to 947 for Washington, DC) and property crimes (6,097 vs. 4,270 for Washington DC) (“Deanwood, Washington, DC Crime”).

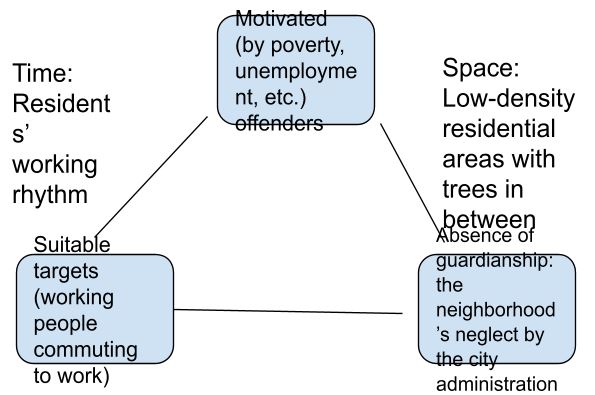

The routine activity theory acknowledges that some dispositional characteristics of Deanwood, such as poverty and restricted access to education, are important in criminal analysis. However, some other situational variables might be as influential in painting the picture of what Deanwood has come to be today. Firstly, the residential area is very low-density, which gives poor visibility to potential witnesses if something illegal is taking place. Dense forestation might be only helpful in concealing criminal activities. Secondly, given that the neighborhood itself does not provide many employment opportunities, its residents must be commuting to work, which leaves their property unattended during the day. Lastly, from an interview with a local resident, it becomes clear that Deanwood is deprived of many city services such as cleaning (Davis). It is readily imaginable how such neglect leaves the neighborhood unsupervised. Image 1 demonstrates exactly how the example of Deanwood fits the model developed by Felson and Cohen.

Today, Deanwood is at the beginning of a long road to safety and prosperity. Davis claims that the neighborhood undergoes a major transition. As of late, it has been gaining traction on the housing market due to its picturesque views and affordable prices. A real estate agent interviewed by Davis said that Deanwood had seen a lot of young professionals buying property. The agent explained that young people are not willing to pay as much as $1,000,000 in more expensive districts in Northeast Washington when they can have a bigger house for $400,000 in Deanwood. Davis concludes that the ongoing gentrification is upgrading the neighborhood and gives it new hope.

According to the routine activity framework, it is very probable that Deanwood lacks safety because it does not have sufficient infrastructure that would imply heightened surveillance. Reese compares Deanwood to another Black-majority neighborhood, Shaw. Shaw shares the history of slavery with Deanwood; however, in the 20th century, it came to prominence and became a center of African-American culture and intellectual life. Shaw housed some of the best-known African American institutions: Howard University, the Whitelaw Hotel, Industrial Savings Bank, and Freedmen’s Hospital. The presence of various businesses and organizations means controlled traffic of people as well as law enforcement.

To let Deanwood bury its problematic past, it is advisable to support local businesses as well as provide city services at a better level. This measure would also improve employment in the area and allow more people to quit commuting and get a job next to their place of residence. Another recommendation would be to foster local initiatives in keeping the neighborhood in order. Davis writes that some time ago, the residents of Deanwood have taken matters into their own hands and organized regular cleanups. Uniting forces and maintaining social bonds would likely reduce crime opportunities in the area or at least improve the reporting rate.

Conclusion

The routine activity theory emerged in the 1970s as a situational alternative to the classic dispositional theories. Felson and Cohen suggested that criminologists focus not on offenders’ motivation but structural changes in society that allow them to commit crimes. The researchers updated the triangle model of offender, target, and guardian and stated that there had to be the convergence of crime and space as well. The theory was especially useful for explaining such paradoxical phenomena as surges in crime despite overall improvements in quality of life. The neighborhood of Deanwood, Washington, DC, fits the model proposed by Felson and Cohen. Because of the low-density residential area, lack of businesses and other organizations, as well as neglect from the city’s administrations, offenders must have plenty of crime opportunities. Further gentrification and support for small and medium businesses might transform Deanwood for the best as they will imply better surveillance.

Works Cited

Ariel, Barak, et al. ““Soft” Policing at Hot Spots — Do Police Community Support Officers Work? A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Journal of Experimental Criminology, vol. 12, no. 3, 2016, pp. 277-317.

Cohen, Lawrence E., and Marcus Felson. “Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach.” American Sociological Review, 1979, pp. 588-608.

Davis, Lester. Deanwood Is a D.C. Neighborhood that’s ‘in Transition’ to Hot Market. 2018. Web.

“Deanwood, Washington, DC Crime.” 2020. Web.

“Deanwood Demographics.” 2020. Web.

DeKeseredy, Walter S., and Molly Dragiewicz. “Introduction Critical Criminology: Past, Present, and Future.” Routledge Handbook of Critical Criminology. Routledge, 2018, pp. 1-12.

“Dr. Marcus Felson.” n.d. Web.

Eck, John, and David L. Weisburd. “Crime Places in Crime Theory.” Crime and Place: Crime Prevention Studies, vol. 4, 2015, pp. 1-33.

Reese, Ashante. The History of Deanwood’s Local Foodscape. 2019. Web.

“Washington, DC Crime.” 2020. Web.

Weisburd, David L., Cody Telep, and Anthony A. Braga. The Importance of Place in Policing: Empirical Evidence and Policy Recommendations. Web.