Shell Strategy Analysis: Introduction

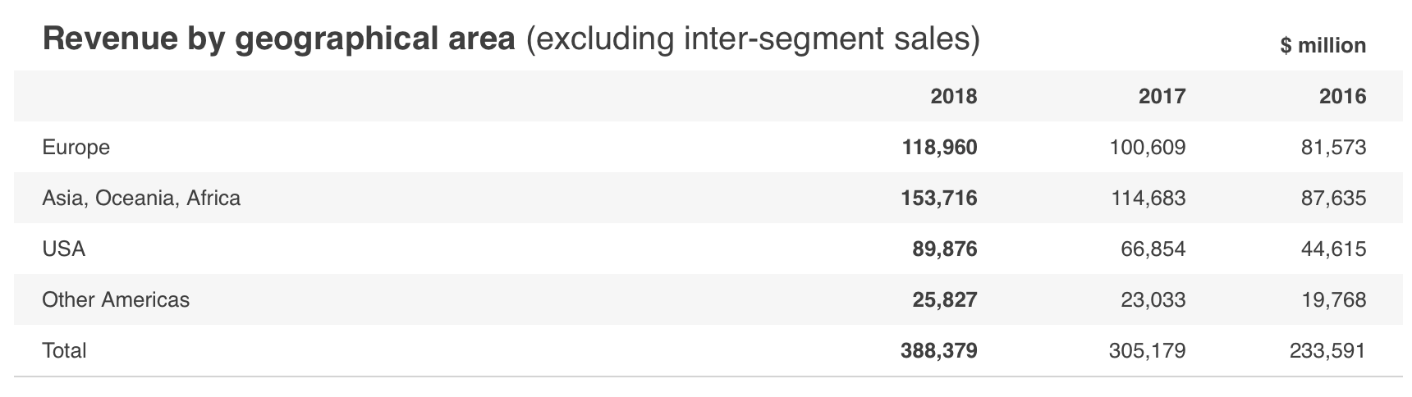

Royal Dutch Shell, or Shell, has established quite a presence in the global market after it captured one of the top spots in the oil and gas industry. Currently known for producing liquefied natural gas (LNG) as its main product, the company has secured its place as one of the main organisations in its selected market (West et al., 2018). According to the company’s recent account of its main activities in its target environment, “It markets and trades natural gas, LNG, electricity and carbon-emission rights and also markets and sells LNG as a fuel for heavy-duty vehicles and marine vessels” (Royal Dutch Shell, 2018).

The oil industry has always been a very lucrative economic environment for setting and running a business, as the examples of multiple modern organisations have shown. The Royal Dutch Shell grounded itself firmly in the specified economic context, prospering exponentially (Briggs, 2016). Although the Royal Dutch Shell company has seemingly secured its role in the global market as the leading company producing oil and the related goods, it will need to sustain its competitive advantage in order to keep its place and reinforce its role in the selected business setting.

Shell Company Analysis: Industry Level

Overview/analysis of energy/gas market

SWOT

The SWOT analysis proves that the Royal Dutch Shell company is in need for reshaping its strategy. The current focus on recycling its old standards of functioning weakens the company’s competitive advantage and prevents it from seeking expansion opportunities, namely, the increase in the scope of its infrastructure and the options for partnerships with other organisations.

In addition, the results of the assessment point to the presence of an evident concern regarding the sustainability issue. The business environment in which the Royal Dutch Shell Company operates is typically deemed as quite environmentally unsafe for quite a good reason (Darko and Kruger, 2017). While the recent additions to the safety standards for oil mining have led to a lesser damage to the environment, oil drilling still has an adverse impact on nature. In addition, the current nature of the drilling process and its technique suggest that any error made during the process immediately imply a spill and the resulting environmental catastrophe. Therefore, the business context in which the Royal Dutch Shell functions can be characterised as rather tense and challenging. Moreover, given the extent of threat, it can also be described as rather demanding regarding the selection of the tools used in the process and the quality of the equipment utilised for oil mining.

Therefore, the company needs to adopt a different framework for managing its resources and especially the waste that it produces as a result of crude oil processing. High rates of environmental contamination, namely, the pollution of water and groundwater, as well as the threats that it posse to the wildlife, have to be curbed by adopting a more sustainable policy. Thus, the Royal Dutch Shell will have to revisit its approach toward risk management and especially its disaster management framework.

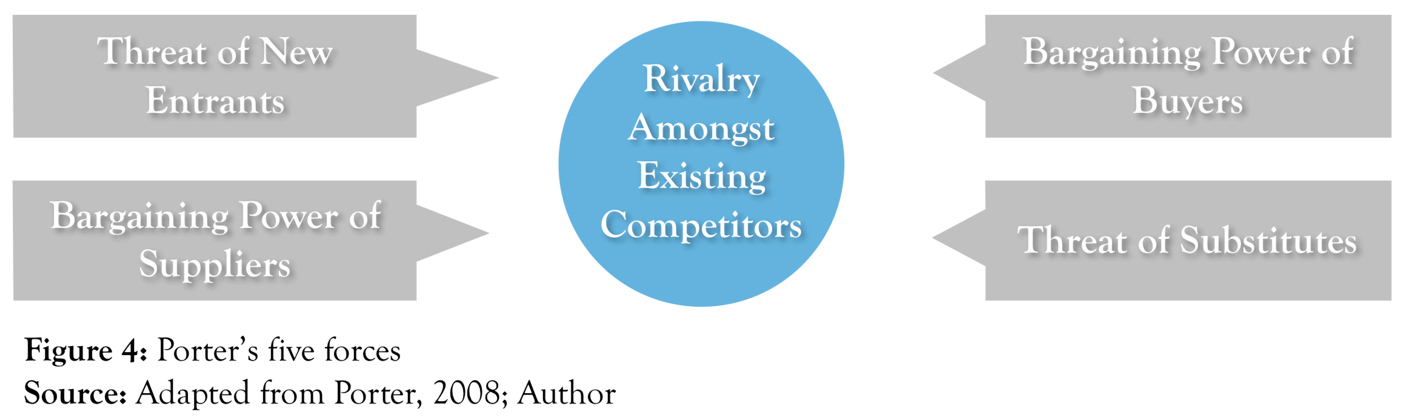

- Threat of new entrants

- Bargaining power of suppliers

- Bargaining power of buyers

- Threat of substitutes

Using Porter’s Five Forces framework, one will realise that Shell has been dealing with an increasing amount of pressure within the industry due to the unhinged rise in the levels of competition. The fact that the company has been considering the use of alterative energy resources as the possible source of its income and, in fact, has already developed a rather impressive framework for its LGN production, shows that the threat of substitutes has been addressed properly. However miniscule the specified threat might be, Shell has secured its position and prevented possible threats of substitutes by creating one of its own. Being a rather clever decision, the specified solution has allowed the company to retain its competitiveness. The introduction of alternative energy resources, namely, LGN, has also helped Shell to address a comparatively high bargaining power of suppliers. Nonetheless, the specified factor still has a tangible influence on Shell and its performance, restricting the amount of power that the company can exert. In turn, the threat of new entrants remains understandably low, with the corporate giants such as Shell and its main competitors serving as severe obstacles on smaller businesses’ way to the oil and gas market.

Shell Business Strategy: Corporate Level

Porter’s generic strategies

PESTLE Analysis

Therefore analysing the greater external environment can help to identify the relevant factors that need to be incorporated into strategy to drive competitive advantages

- Political

- Economic

- Social

- Technological

- Legal

- Environmental

PESTEL Analysis: Shell

As shown above, the PESTEL assessment of the setting in which the Royal Dutch Shell organisation has established its presence also points to the fact that it lacks effective prevention measures against the threat of an environmental change. Although the existing legal standards fully recognise the importance of the standards for addressing the threat of a spill and the need to minimise the negative consequences of oil mining, the company has been failing to focus on the issue of environmentalism. In turn, recent regulations concerning the taxation on carbon emissions imply that changes need to be made to the

Therefore, the PESTEL assessment results indicate that the market context in which the Royal Dutch Shell Company works is extraordinarily competitive and organised based on rigid environmentalism standards. The described characteristics are quite predictable and mostly inevitable given the industry in which Royal Dutch Shell operates.

In turn, the economic aspect of the setting in which Royal Dutch Shell functions shows that the target setting is vastly lucrative and offering extensive opportunities for the organisation to prosper. The oil and gas industry has been thriving despite the negative effects that it produces and the threat that it poses to sustainability. The reasons behind the stellar success of the oil and gas industry is quite understandable given the fact that it produces the goods that can be characterised as limited common resources.

Business Level

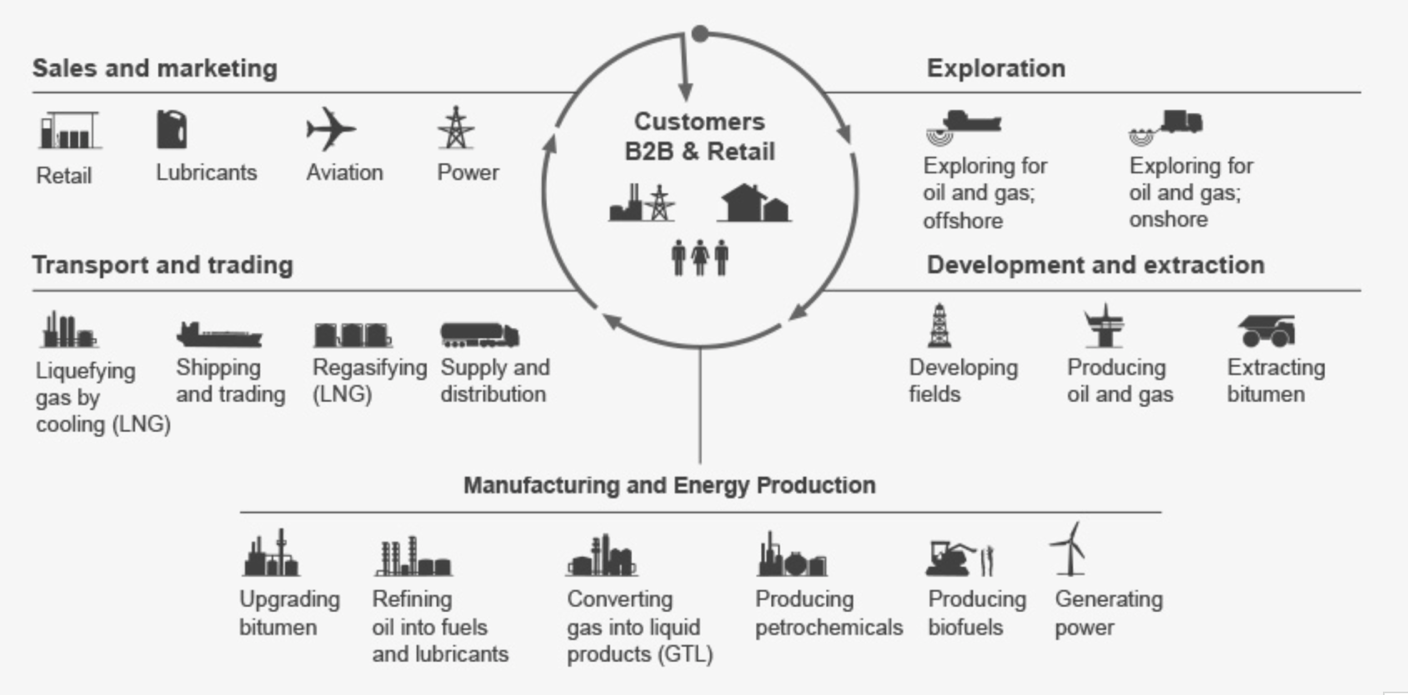

An inside-out perspective of the firm, through business model analysis, can help to analyse internal cyclical relationships

Business model

The current business model of Shell is quite intricate, yet it has been the reason for the company’s ongoing stunning triumph in the global oil and gas market. Specifically, the concept of cross-selling as the main method for Shell to manage its business relationships and gain profit has been the dominant principle for Shell for a while. The idea of selling the products that are only distantly related to oil and gas has helped Shell to expand and garner the attention and appreciation of customers worldwide (Vyas and Raitani, 2018). Arguably, the specified business model has been the driving force behind Shell’s comparatively recent decision to shift its focus from the oil and gas industry to the LNG products (Royal Dutch Shell, 2019).

When considering the benefits of the current business model used by Shell, one should admit that it opens extensive business options, allowing the firm to trade in oil and gas, simultaneously developing its LNG production. Therefore, the firm has expanded its portfolio to the point where it has become outstandingly diverse, incorporating experiences not only in the production of LNG but also in the liquefaction of natural gas (GTL). Moreover, the products such as “gasoline, diesel, heating oil, aviation fuel, marine fuel” and many others have been included in Shell’s portfolio (Royal Dutch Shell, 2018). Therefore, the concept of cross-selling has been serving its purpose of galvanising Shell’s performance and encouraging its progress in the global oil and gas market since the company decided to diversify its portfolio. However, it is worth admitting that the specified approach has its disadvantages. For instance, the necessity to disperse quality control into multiple streams so that every product could receive the required amount of attention poses quite a challenge to Shell, which is understandable given the need to keep the consistent focus on multiple issues (Bellucci and Tofi, 2017).

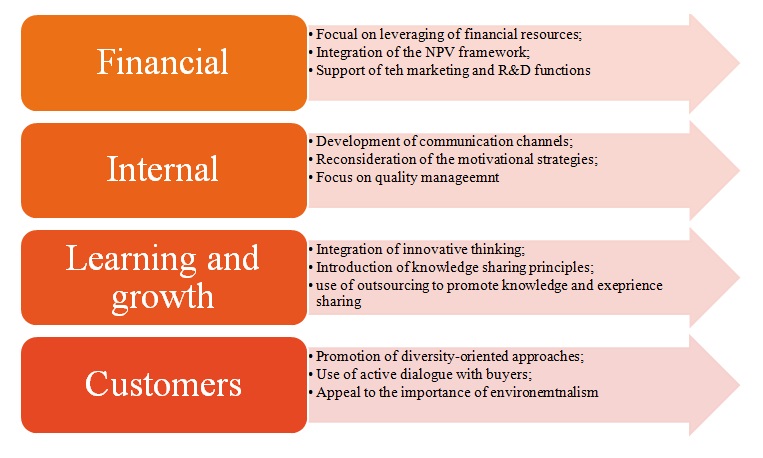

Balanced Scorecard

Using the Balanced Scorecard approach toward assessing Shell’s business strategy allows proving that the organisation has advanced in its SCM and marketing to a great extent. As Figure 3 below shows, Shell has been balancing its internal, financial, learning, and customer-related activities quite well, having created an approach that links the specified activities into a single model. Specifically,

However, in order to improve its competitive advantage and accumulate a greater number of resources, at the same time expanding into the larger market, Shell will need a better connection between the specified activities and the rest of the corporate processes. For instance, the financial tasks will also have to involve allotting money for Shell’s R&D as the means of exploring alternative options for obtaining energy aside from the ones that it has built so far. In addition, Shell will have to allot a certain amount off finances to subsidise a new marketing campaign that will help to attract new business partners, investors, and potential customers, thus expanding Shell’s supply chain even further. Finally, the current Balanced Scorecard shows that the company could use a closer focus on the promotion of innovative thinking in its setting so that new opportunities for business development could be explored. Finally, the necessity to motivate staff members and keep the levels of their engagement high deserves a mentioning as a critical component of the company’s internal perspective (Ossorio, 2018). In fact, the introduction of innovative ideas and the pursuit of product differentiation and diversification can be seen as the Industry value chain evolution within Shell (Teoh and Abu, 2018). To address the specified concern, Shell will have to create additional communication channels that will help to coordinate diversity-related issues and forward the concept of cross-disciplinary cooperation within the organisational setting.

Organisation

Upstream

The upstream processes within the company have been centred around the diversification of its production line. Remarkably, the described strategy has not always been the case; prior to the change that the organisation’s supply chain underwent in 2005, Shell used to follow the principles of the fourth party logistics, as well as the SAP and APO sales system (Frederico, 2018). However, once the necessity to expand emerged, Shell switched to the described approach, which it has been using to date. The benefits of the specified framework are obvious as it allows the company to embrace a vast range supplies. However, the need to perform multiple minor transportations increases the cost of the upstream SCM and the associated inbound logistics processes (Wong et al., 2018). Therefore, redefining Shell’s upstream framework could be seen as a possibility in the future.

Downstream

In turn, the downstream processes within Shell are restricted to the trade of refined oil and other goods produced by the organisation, including some of the recent innovative ones, such as LNG mentioned above. The company also includes its chemical-related activities into its downstream process as an integral part of the distribution stage of its supply chain. The downstream processes are managed and monitored with the help of the latest technology at Shell, which makes the end result particularly attractive to end customers (Riberio et al., 2017). Therefore, the focus on quality and production control can be regarded as critical constituents of Shell’s competitive advantage. Indeed, when comparing its SCM to that one of other companies in the oil and gas industry, one will concede that the issue of quality management is what makes Shell stand out among others.

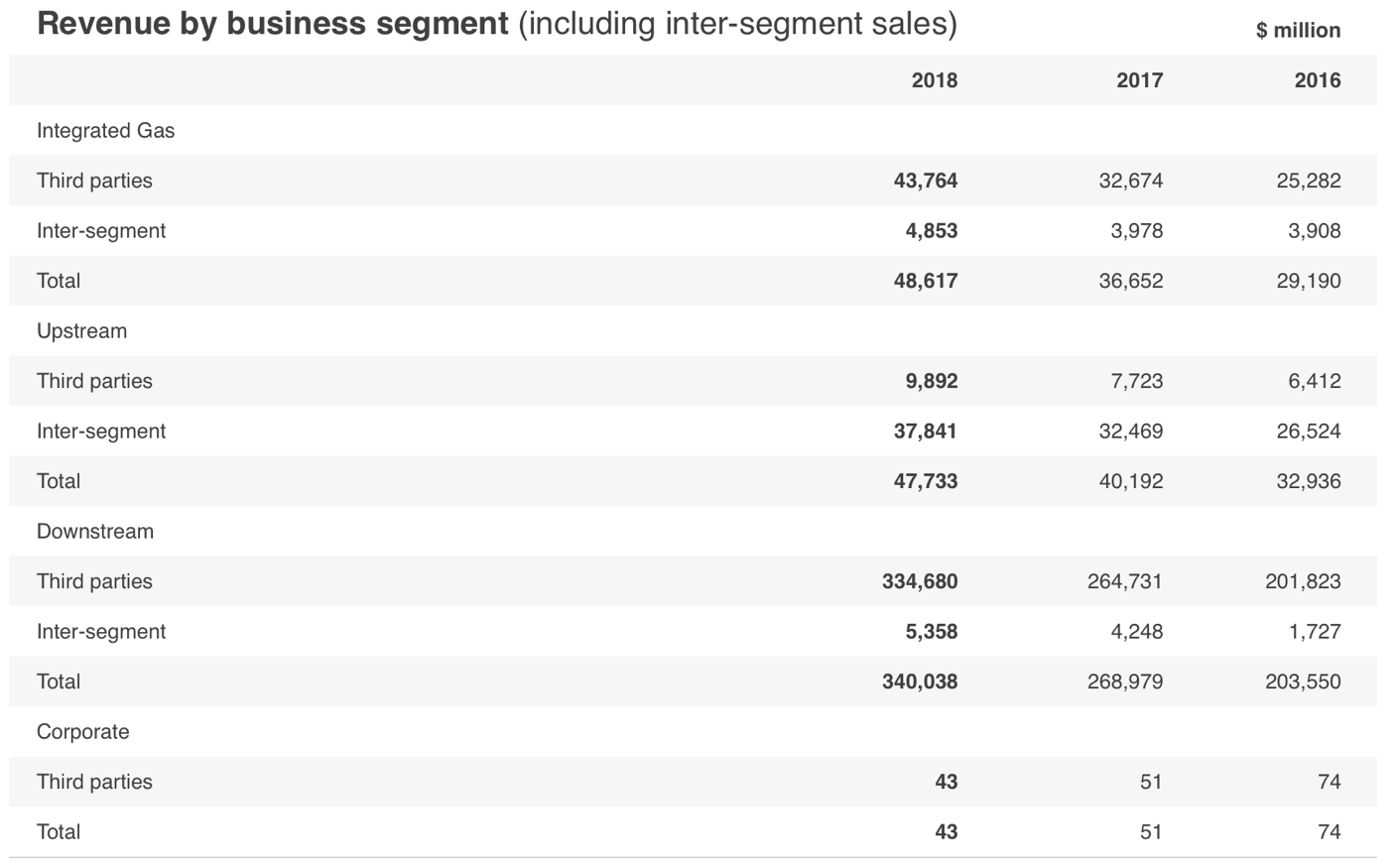

Projects & Technology and Segmental Reporting

The current approach toward segmentation within Shell is another constituent of the company’s competitive advantage that can be amplified in the future. Shell will have to introduce innovative tools for maintaining positive performance in each of its segments, which means that the company will possibly require a different approach to corporate governance. Thus, decision-making in each segment will be made based on the unique factors that define the quality of the end product and active collaboration among staff members.

Technology and innovation: Co-opetition and Growth

Shell will also require a platform based on the notions of co-opetition and growth, which will suggest the integration of incremental innovation into its design. In addition, the idea of utilising disruptive innovations as the means of forwarding Shell’s progress can be considered a possibility (Kumar et al., 2017). By using emergent innovative solutions as a potential advantage, Shell will benefit significantly.

Blue Ocean Strategy

Currently, the company is at the crossroads of diversifying its products and minimising the production cost/ In order to address the specified issue, Shell will need the Blue Ocean Strategy, which helps to define the trade-off accurately and, thus, delineate the financial framework for the future decision-making. Currently, Shell will have to locate its trade-of by achieving the balance between cost and value with the help of an innovation-driven approach and the redesign of its infrastructure, with the choice of a single supplier and the relocation of the firm closer to the said supplier (Qudah et al., 2018). Thus, the transportation expenses will be minimised, and the Blue Ocean Strategy will be implemented.

Resource Based View Analysis

The resource-based framework will be utilised to analyse their competitive advantages.

VRIO

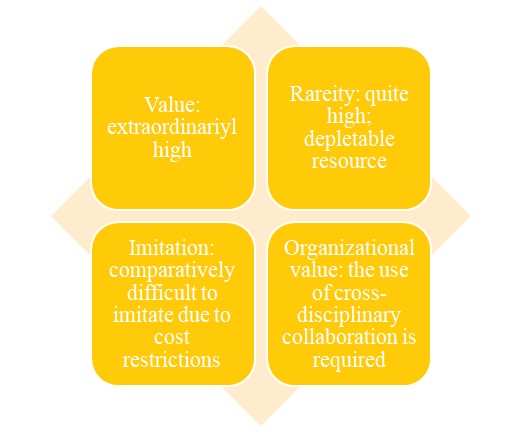

- Valuable

- Rare

- Difficult to imitate

- Supported by organisations

Using the VRIO framework, one will realise quite easily that Shell’s current competitive advantage hinges primarily on one of the aspects thereof. While one might claim that the products delivered by the organisation, including the entirety of its vast portfolio, are extensively supported by the organisations that need the specified products to sustain their performance (Mendes, 2018). However, the value of Shell’s products is the main selling point and the key characteristic that holds the rest of the aspects of the VRIO framework together. While the value of oil is extraordinarily high alone, the production of LNG, GTL, and a vast range of other products that single out Shell as a unique company with a huge potential add to the company’s competitiveness.

As the VRIO analysis above shows, it is imperative that Shell should be supported by other companies so that it could continue to deliver high-quality products. Given the firm’s recent foray into the exploration of alternative fuel options, the significance of R&D within the organisation is becoming exponentially high. Herein lies the urgency of rearranging the firm’s resources to focus on the specified aspect of its performance, at the same time maintaining high quality and communication with stakeholders.

Strategic Challenges

Current strategy and issues

Despite having been delivering quite an impressive performance and retaining its 11th spot as one of the most powerful companies in the oil and gas industry, Shell still has multiple challenges to overcome. As the assessment performed above has shown, the company needs to reinforce its sustainability practices so that it could retain its competitive advantage and keep its reputation.

Overall, the current competitive strategy that Shell uses as its default approach is based on the diversification of its product, search for expansion opportunities, and focus on the rearrangement of its inventory planning. The described framework helps Shell to keep its processes in order and run them smoothly, which is critical given the range of products and the number of minor SCM subsets that Shell has to manage. However, the application of the SAP and APO sales system combined with the focus on diversification also leads to lacklustre management of the cost issue. Therefore, Shell will have to redesign its supply chain to reduce the costs for inbound transportation, at the same time introducing the principles if VMI into its perspective (Radzuan et al., 2018). As a result, the firm will receive a greater leeway in managing its resources.

Suggestions

Future Outlook and Strategic Challenges

Although the industry in which the Royal Dutch Shell operates can be characterised as very lucrative, its environment is highly competitive, which suggests that the company should focus on using every possible opportunity that its target setting offers. Thus, despite the impressive experience and quite substantial amount of competitive advantage that the Royal Dutch Shell organisation possesses in the market of its choice, the company may risk losing its assets and the loyalty of its customers. Unless changes are made to the company’s current performance, Royal Dutch Shell may lose its competitive advantage followed by the reduction in its profit margins and performance rates. The issue of transportation and the redesign of Shell’s inbound and outbound logistics will have to be considered a crucial change.

References

Bellucci, A., & Tofi, M. (2017) Classification of business models of Italian bank assurance by balance sheet indicators. International Journal of Economics and Management Engineering, 11(7), pp. 1907-1910.

Briggs, C. A. (2016) Global outsourcing: prerequisite to sustainable competitive advantage within the oil industry. International Journal of Business Research and Information Technology, 3(1), pp. 18-35.

Darko, G. and Kruger, J. (2017) Determinants of oil price influence on profitability performance measure of oil and gas companies: A panel data perspective. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 5(12), pp. 1-8.

Frederico, G. (2017) Supply chain management maturity: a comprehensive framework propos‑al for literature review and case studies. International Business Research, 10(1), pp. 68-77.

Kumar, A., Kumar, R., Dutta, S. K., Kumar, R., & Mukherjee, A. (2017) Reconceptualising co-opetition using text mining: inductive derivation of a consensual definition of the field (1996-2015). International Journal of Business Environment, 9(2), pp. 114-137.

Mendes, M. V. I. (2018) The winding road of corporate strategy. Revista Pensamento Contemporâneo em Administração, 12(1), pp. 33-46.

Ossorio, M. (2018) Does R&D investment affect export intensity? The moderating effect of ownership. International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting, 10(1), pp. 65-83.

Qudah, M. A. A., & Hashem, T. N. (2018) The impact of applying the blue ocean strategy on the achievement of a competitive advantage: a field study conducted in the Jordanian telecommunication companies. International Business Research, 11(9), pp. 108-118.

Radzuan, K., Omar, M. F., Nawi, M. N. M., Irwan, M. K., Rahim, A., & Yaakob, M. (2018) Vendor managed inventory practices: a case in manufacturing companies. International Journal of Supply Chain Management (IJSCM), 7(4), pp. 196-201.

Ribeiro, R. B., Pereira, V. S., & de Sousa Ribeiro, K. C. (2017) Estrutura de capital, internacionalização e países de destino de empresas brasileiras: uma análise da hipótese upstream-downstream. Brazilian Business Review, 14(6), pp. 575-591.

Royal Dutch Shell, (2018) Integrated gas. Web.

Teoh, B., and Abu, N. (2018) Sustaining competitive advantages in Malaysian electrical and electronics industries context. International Journal of Supply Chain Management, 7(1), pp. 43-50.

Vyas, V. and Raitani, S. (2018) Understanding the role of web-benefits in cross-buying. International Journal of Electronic Marketing and Retailing, 9(1), pp. 1-21.

West, J., Chu, M., Crooks, L., & Bradley-Ho, M. (2018) Strategy war games: how business can outperform the competition. Journal of Business Strategy, 39(6), pp. 3-12.

Wong, W. L., Husain, R., & Sulaiman, A. (2018) Managing upstream and downstream relationships in supply chain for military organisation. International Journal of Business and Management, 2(1), pp. 72-77.