Abstract

Attention towards the reduction of financial crime, corruption, and fraud in Saudi Arabian financial institutions has advanced significantly in recent years; as a priority, several legally acceptable mechanisms have been instituted to bring about more realist financial transactions. The effectiveness of these mechanisms, however, raises concern. This is because there is an equal advancement in the sophistication of crime and crime-network that continues to threaten efforts to bring the position of financial practices in Saudi Arabia to sanity. There is also the challenge to put to effective us legal/regulatory requirements that would ensure total sanity against fraudulent financial activities in the kingdom.

This pro-regulatory disposition is nimble and shifts away from fundamental economic arguments that favour legally acceptable regulations for ensuring the preservation of trust-based norms necessary for sanitising the Saudi Arabian financial sector. As instituted by corporate-financial-law (CFL) in the kingdom, Islamic banking is also fast gaining acceptance in/outside of the kingdom. CFL has become a familiar phenomenal that has impacted on banks, lowered margins/operating costs while it upholds profit marking. Based on the massiveness of the Saudi Arabian financial sector, and the controlling or restricting competitions, enhancing an efficient modulation of the sector has been tasking. Therefore, this work is inclined towards the examination of fundamental elements that affect corporate finance directly or indirectly due to legal developments and procedure in the Saudi Arabian Kingdom.

A General Overview of Corporate Finance Law, Corruptions and Fraud in Saudi Arabian Financial Institutions

The Concept of Corporate Finance Law and, Corruptions and Fraud in Saudi Arabian Financial Institutions

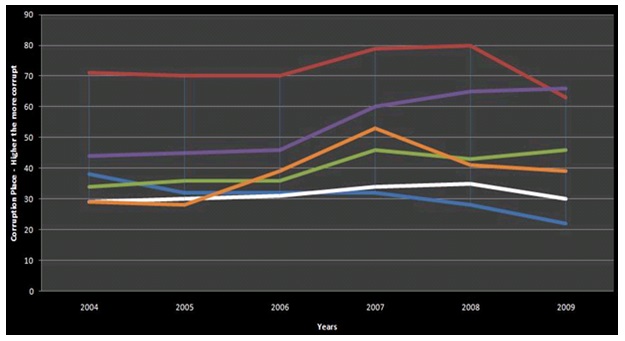

Attention towards the reduction of financial crime, corruption, and fraud in Saudi Arabian financial institutions has advanced significantly in recent years; as a priority, several legally acceptable mechanisms have been instituted to bring about more realist financial transactions. The effectiveness of these mechanisms, however, raises concern. This is because there is an equal advancement in the sophistication of crime and crime-network that continues to threaten efforts to bring the position of financial practices in Saudi Arabia to sanity. Figure 1 illustrates-Corruption Perception-Index in Saudi-Arabia within the period 2004-2009. Equally Table 1 identifies the ease with which financial institutions in a number of countries including Saudi Arabia permitted doing business in 2008 and how this affected corruption-perception-index – the values shown in the table are ratings of the various countries against the international community. These indicators suggest that financial institutions in the kingdom are under the threat of corruption/fraud- even though the threat appears to have reduced since 2008.

It has been noted that ‘financial institutions are particularly vulnerable due to the nature of their businesses and the volume of transactions and client relationships they manage’. There is also the challenge to put to effective us legal/regulatory requirements that would ensure total sanity against fraudulent financial activities in the kingdom.

Table 1. The ease with which financial institutions in a number of countries, including Saudi Arabia, permitted doing business in 2008 and how this affected corruption-perception-index.

Therefore, corporate finance law is an effort to inter-relate corporate-finance and law with a primary focus of understanding, ‘how incorporated firms address the financial crimes that affect their investment decisions by using varied financial instruments that give holders different claims on the firm’s assets’. The significance of aligning corporate-finance to best legal mechanisms, therefore, becomes obvious, particularly in helping the understanding of how/why financial institutions adopt certain policies to rule their capital-structure.

There are enormous effects associated with financial crimes – as reflected in previous studies, including its potential of stampeding development of financial evaluations; but on the other hand, such crimes prompt legal regulations and policy reformations which are usually necessary for an enhanced economy. Certain studies have identified peculiar characteristics of institutions affected by corruption and fraud globally, and by extension in Saudi Arabia. However, it is equally true that corruption and fraud are factored by the human aspiration to satisfy ego as much as it is driven by environmental influences. Awkwardly, however, corporate institutions and individuals have, ‘neither the obligation to make disclosure when any reasonable doubt exists concerning corrupt or fraudulent acts [in most Saudi Arabian institutes]’.

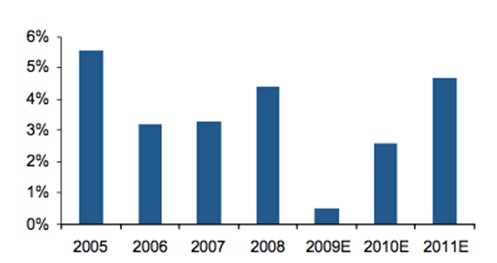

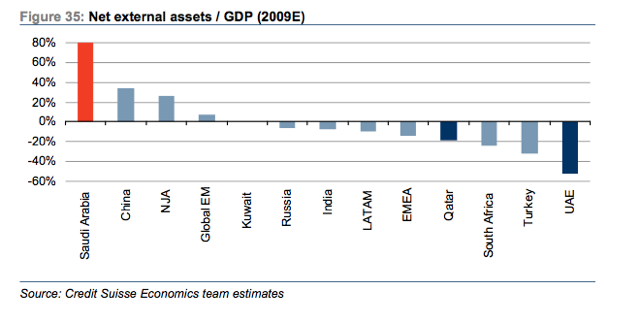

Otherwise, individuals and organisations are adamant of reporting corrupt/fraudulent acts as they shy away from been identified with such. More so, the war against corruption and fraud is considered to be the government’s concern more than it is the individuals’ or more than it is the institutions’. This pro-regulatory disposition is nimble and shifts away from fundamental economic arguments that favour legally acceptable regulations for ensuring the preservation of trust-based norms necessary for sanitising the Saudi Arabian financial sector. Resultantly, the law becomes dispensable and obsolete without a propelling force to be maximally effective in addressing corruption and fraud in the kingdom. Maxin has however reported fresh efforts to make the most of the legal toolkit of law in addressing corruption and crime in the kingdom; this consequently is reflecting on the GDP growth of the kingdom, as shown in figure 2.

Therefore, this work is inclined towards the examination of fundamental elements that affect corporate finance directly or indirectly due to legal developments and procedure in the Saudi Arabian Kingdom. Even though the evolution of the legal environment in Saudi Arabia has been notable lately (as reported by Maxin), there is still so much to be done to ensure more acceptable sanity against corruption and fraud in corporate institutes in the kingdom.

History

Over time, several financial institutions in Saudi Arabia have applied various legal processes and laws in regulating their financial transactions – some of the regulatory applications are usually stiff whereas others are lenient based on the intensity with which they subject offenders to punishments. It has been identified that legal attention is geared towards the thriving of ‘anti-bribery and corruption, anti-money laundering and mortgage fraud as specific areas of focus’. Appendix 1 shows some indicators of necessitating corruption/fraud in the financial sector of Saudi Arabia. Some effort aimed at addressing corruptions and fraud in Saudi Arabian financial institutions includes:

- Proactive technicalities in the implementation of policies and governance, control-assessments, technology-solutions as well as due assiduousness assignments, and

- Reactive assistances about investigation/remediation.

Based on the outcome of heavy losses recorded in Saudi Arabia by financial-institutions due to fraud and corruption, stabilising and indeed fortifying the sector against financial crimes is eminent. From studies, stabilisation of the corporate financial sector in Saudi Arabia is achievable through an increased capitalisation-strengthening as well as through appropriate supervisions. In as much as this suggestion may be accepted, it has failed to address the human-driven ego or the will of individuals to indulge in financially corrupt/fraudulent acts which are notable with financial crimes. Lately, there is the introduction of Islamic-banking aimed at checking out financial crimes (corruption/fraud) within the banking sector in the kingdom, and to bring maximum benefit to customers- this model has so far proved to be effective in regulating transactions between individuals and banks in terms of exposing fraud/bribery.

As instituted by corporate-financial-law (CFL) in the kingdom, Islamic banking is also fast gaining acceptance in/outside of the kingdom. CFL has become a familiar phenomenon that has impacted on banks, lowered margins/operating costs while it upholds profit marking. Based on the massiveness of the Saudi Arabian financial sector, and the controlling or restricting competitions, enhancing an efficient modulation of the sector has been tasking. Watts & J Zimmerman in a study noted that ‘protecting users of financial systems from abusive behaviour by the financial institutions, creating equality in the competition between banking institutions, and tackling the problems caused by potential conflicts of interest is a “fairness” issue’. This is accounted for by the fact that ‘there are tradeoffs between three criteria for evaluating financial regulation and structure’. But on the whole, the adaptation, or the application of corporate financial laws in Saudi Arabian financial institutions promises fruitfulness towards a more regulated financial sector through an effective checkout of bribery/corruption.

Definition

Corporate finance law as applicable to the Saudi Arabian financial sector constitutes a form of regulation/supervision that brings financial institutions in the kingdom to a number of restrictions/guidelines by ensuring that a number of requirements are met in legal dimensions. This is necessary to bring about sanity in the sector and ensure investor-trust and financial balances.

Corporate Finance Law in Saudi Arabia

With reference to a ministerial decision dating 21-7-1420h in Saudi-Arabia, SAMA was given powers of conducting supervision as well as regulation of activities carried out by Saudi-Arabian leasing institutions/companies – this was duly referenced and aligned to an Anti-Money-Laundering (AML) law that came into existence as a result of Royal-Decree No: 39/m dating 25-6-1424h. The law was developed upon, ‘the implementing regulations, which stated in Article (4) that “Financial and Non- Financial” Institutions may not carry out any financial, commercial or similar operations under anonymous or fictitious names’. Equally, ‘they must verify the identity of the client, on the basis of official documents’.

The law was also found under the ground Article (6) by which, ‘Financial and Non-Financial Institutions must have in place internal precautionary and supervisory measures to detect and foil any of the offences stated herein, and comply with all instructions issued by the concerned supervisory authorities in this area’. In addition to the correspondence of SAMA dating 23-5-1424h, this was followed by regulations for checking out money-laundering as well as terrorism-financing-transactions which was directed at companies that lease.

As an effort to meet up with domestic and/or foreign occurrences as well as demands in the interest of fighting out money-laundering, fraud, corruption, and terrorism-financing, it is noted that ‘SAMA has issued Anti-Money-Laundering/combating-the-financing-of-terrorism (AML/CFT) instructions aimed at protecting financing companies and their customers against illegal transactions involving money laundering and any other criminal activities’. This is to enable the enhancement of integrity/safety of the financing-sector in Saudi Arabia and equally bring about the promotion of individuals’ confidences in financial activities of the regulated institutions. Fama & Michael in a study on effecting the credibility of SAMA specified the jurisdiction SAMA’s influence to comprise regulation of financial institutions under the guidance of the law- through this means the regulatory agency focuses on the control, detection, regulation, and prohibition of corruption/fraud and money-laundering.

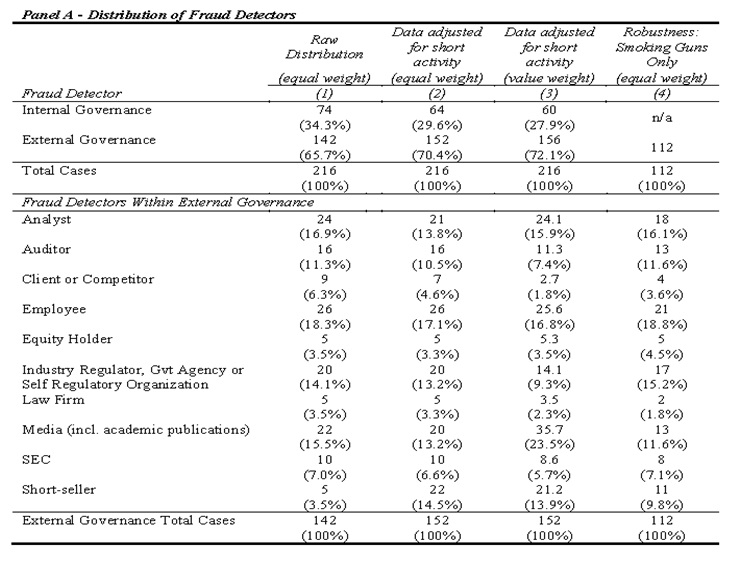

Based on the regulatory authorisations, SAMA is therefore committed to ensuring that implementing the instructions is effected in totality by each financial-institution that is SAMA-licensed. This SAMA achieves in the course of carrying out o-site monitoring procedures or in the course of its reporting, as well as in preparing compliance certificates which are done by external auditors. The various levels of fraud detection in the kingdom were review in a study, as shown in Table 2. This table shows clearly that legal efforts to combat fraud/corruption in the kingdom are basically government-driven.

The table was generated as an effort towards the identification of fraud/corruption of internal-governance of Saudi Arabian financial institutions. The first column depicts the original coding. The second reflects fraud/corruption detector responses and control. The third is a reflection of the adjustment of the second column (where funds were used in settlement of fines) – this adjustment was necessary to define winsorised settlement-value. It was realised that at various stop-points, participants in the governmental transaction do not reflect true reflection of fines/settlement, thus constituting fraud/corruption.

Corporate Finance Law in other Current Federal Statutes

There is a massive increment in the rate at which organised crime is advancing globally; most specifically, these crimes (including corruption and fraud) are advancing through complicated network-systems that span across countries. Resultantly, financial-institutions; most of which are directly in touch with the public and transact voluminous businesses each day; are exposed to the dangers posed by such crimes. In the United Kingdom, the United States, and several other nationalities, governments have seen this as a threat to the stability of the economy and hence that of development; thus, there is a response in terms of enactment of laws and appropriation of regulations for the sole interest of standardising financial sectors.

From studies conducted recently, it was realised that ‘there is an increased willingness of regulators to pursue individual firms and impose tougher penalties for breaches of regulations, particularly in the area of bribery and corruption where some unprecedented fines have been levied’. In the United States, for example, agencies saddled with the responsibility of prosecuting offenders have equally levied huge fines for Non-United State financial-institutions who are involved in corrupt or fraudulent acts. Whereas in areas that have something to do with sanctions/market abuses; there is also continual attention from the Financial-Services-Authority (FSA). Addressing development in the FSA recently, Grundfest noted that the agency has become more regulatory conscious lately such that, ‘published business plan highlights anti-bribery and corruption, anti-money laundering and mortgage fraud’. This development is interesting not just because it is an inch by inch monitor of fraud and corruption; it may also instil in an official who handles public-funds the consciousness to be more realistic with public transactions. The expectation is that regulators must continue with addressing systems and continue to control outcomes that pose threats to the wellbeing of the financial sector through thematically reviewed laws.

Review of Current Litigation

Of late, the financial sector in the kingdom has witnessed a significant increment in a number of small/medium size investments. It is noted from studies that, ‘with encouragement from the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency, Saudi banks are competing with regional and international financial institutions by developing and offering many open-ended and close-ended funds to the investors’. Based on this, there is an approval from the finance minister for the regulation of the sector aimed towards equitable management of investment funds as well as for an effective collection of investment-schemes which Saudi-banks offer. The regulatory litigations are aimed at addressing some issues that are inclined towards establishing, operating, or marketing of open-ended/close-ended mutual funds. Intentionally, the minister hoped that regulating the financial sector in Saudi-Arabia would bring about:

- protection of the numerous investor in the kingdom;

- ensure that only well managed and reputable institutions with adequate capital offer these services;

- ensure that the quality of services and the efficiency of the market are enhanced, and its credibility strengthened, and

- promote the development of supervisory standards in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region.

The clearly outlined regulations were targeted towards the following:

- The Agency’s policy is to permit only Saudi Banks to offer such products and services to the public in Saudi Arabia- the Saudi banks are requested to play the role of a Fund Manager. In this regards, the Banks may also act as custodians, administrators and marketers or may delegate some of these functions to other financial institutions; nevertheless, they must take full responsibility for the management of their Investment Funds and remain accountable to the public and the authorities in the kingdom at all times;

- Organisational capability: in granting a Saudi Bank permission to establish and market such funds, SAMA makes an assessment of its organisational capability and the managerial expertise at its disposal- banks that are planning to offer these products must have the organisational structure, the operational accounting systems, and the decision-making and control procedures that are essential for providing efficiency as well as cost-effective, profitable service. Banks must also have appropriate managerial talent and expertise in this area;

- Capital Adequacy: Saudi Banks wishing to offer these services must be well-capitalised and meet all regulatory and legal capital requirements- while such services are of a fiduciary nature and do not require allocation of capital for credit risk; in practice, a strong capital base provides comfort to investors and the regulatory authorities for any losses that may arise from management negligence or fraud;

- Management Capability: an important factor in granting permission to a Saudi Bank is the competence and integrity of its management, which is assessed against the following criteria: Persons acting as managers should possess adequate qualifications to carry out their responsibilities including appropriate technical knowledge – the individuals must also have appropriate professional experience-

- Such persons must have probity and soundness of judgment commensurate with their positions;

- Such Persons are expected to fulfil their responsibilities with diligence and to protect investors.

It is expected that a person managing such funds:

- Has not committed an offence involving fraud or dishonesty;

- Has not contravened or broken any laws or provisions in any jurisdictions that were aimed at protecting investors and depositors;

- Has not engaged in any business practices that appear to the agency as deceitful, oppressive or which reflect discredit in his methods of conducting business;

- Funds Domiciled in Foreign Jurisdictions: from time to time, for operational and other reasons, a Saudi Bank may wish to establish an investment fund outside Saudi Arabia- in some instances, this may be in the form of a separate legal entity; in such cases, the Saudi Bank is required to obtain the Agency’s Approval prior to the establishment of such a fund. The bank should also ensure that it complies with the laws and regulations of Saudi Arabia and those of the relevant foreign jurisdiction;

- Borrowing by the Fund: Specifically, borrowing by a fund shall be limited to a percentage of its net-assets value as agreed with the agency at the time of the establishment of the fund; this borrowing from the bank or from any other source shall be at the best available market rate. Funds derived from repurchase agreements (Repos) activity shall be considered as borrowings in determining the permissible borrowing level;

- Restriction on Investment Powers: as indicated in section 6 of the Regulations, the agency shall issue guidelines to the Banks on the following restrictions on their investment powers- these shall be updated periodically to reflect the changes in the market conditions. Currently, these shall be as follows:

- A fund shall not be permitted to invest more than 10% of its net assets in another mutual or investment fund; furthermore, such investments shall not exceed 15% of the net assets of the acquired mutual or investment fund;

- A fund shall not invest more than 1% in the outstanding capital of a Saudi company that is traded in the shares market;

- The exposure of a fund to a single counterparty or to a group of related counterparties shall not exceed 15% of its net assets value;

- Investment by a fund in single equity or debt issue shall not exceed 10% of its net assets.

All these have been put in place to institutionalise maximum sanity against corruption and fraud, as well as other financial criminal acts within Saudi Arabia. Appendix ‘B’ presents Sarbanes-Oxley Acts that are enacted to foster sanity against corruption/fraud in the kingdom.

Aim of the Study

The aim of this paper is to actualise the following:

- To evaluate the state of corruptions and fraud in the Saudi Arabian financial sector and determine possible causes of corruption/fraud in the Saudi Arabian financial sector through an analysis of economic indicators;

- To evaluate the effectiveness of corporate financial law in addressing corruptions and fraud within the sector; and

- To extrapolate from the findings regarding the development of the current system of financial law the suggestion for financial, legal reforms that are likely to be implemented in response to the recent financial crisis, and thus identify areas of improving or strengthening the CFL’s applicability to control of fraud/corruption in Saudi Arabia’s financial institutions.

Literature Review

Contrasting Corporate Finance Law in Saudi Arabia to Other Places

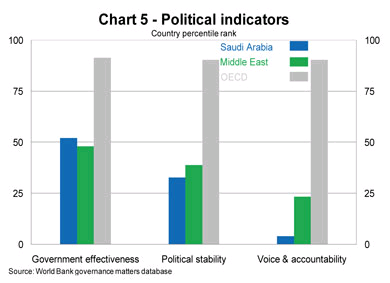

The evolution of corporate finance law in Saudi Arabia, particularly as put to effect by SAMA, could be placed shoulder to should with world best legal processes especially as these laws are assuming better states of stability. Referring to the development of new bribery acts in the United Kingdom for instance, as well as with the continual regulations within the region, anti-bribery/corruption compliances in Saudi Arabia may be considered as been of utmost importance towards the strengthening of the financial sector. The primary objective(s) for enacting the laws would become obsolete; financial institutions must always go beyond getting familiar with laws in order to comply with requirements therein. To articulate the implementation of practising corporate finance laws, it has been noted through studies that, ‘companies need to first understand more about the new Acts including the penalties and offences, the defence of “adequate procedures” and the differences between the new legislations and Foreign Corrupt Practices Acts [FCPA]’. The effect of political indicators on the regulation of corporate finance law in Saudi-Arabia is presented (as was determined by World-bank in 2010) in Figure 3 as follow:

Corruptions and Fraud in Saudi Arabian Financial Institutions: the Banking Sector

An estimated 11.3% level of corruption was noted in Saudi Arabian financial institutions recently (majorly driven by the banking sector). Worrisomely, efforts have been put together to equip the sector against corruption/fraud; specifically as regarding the classification of e-banking services/products based on security requirement levels for enhanced performances as noted thus:

- Customer Originated Transactions (individual transactions): this profile relates to the provision of transactions, where the customer can specify the beneficiary, the amount and the date without prior arrangement or subsequent additional authorisation. This profile is the main focus of this document – banks may decide to sub-divide this profile depending on the transaction amount, or other parameters of the transaction; and

- Customer Recruitment and Registration (sign-on): This is the highest risk profile because customer recruitment and registration form is the basis upon which all future security rests and so must be treated with the greatest care- this profile also includes the ability to alter the customer’s name, address or authentication data.

Banks in Saudi Arabia have the responsibility of ensuring the provision of safe and sound services to clients. This they do under the following obligation:

- Banks are to authenticate processes necessary to initially verify the identity of new customers (and ensure that the identity of the customer is verified and proven correct before they start any kind of relationship) – this process is especially important with new customers located outside the area of the bank’s physically location;

- Banks are to authenticate processes to identify existing customers who access e-banking services, for any usage of the e-banking offerings, at different levels: login, transaction, orders, confirmations, and log off;

- Losses from fraud if the institution fails to verify the identity of individuals or businesses applying for new accounts or online credit- banks have to know their customers and define ways for explicit identification;

- Protection of the bank’s customers from online fraud attempt (Phishing and Pharming Attacks) through the use of service that enables prevention, detection and response to these attacks, as well as the protection of the bank’s identity online from illegitimate use or misrepresentative abuses;

- Taking legal actions against any illegitimate representation of the bank or any illegitimate use of the bank’s identity online regardless of the purpose; and

- Education of the bank’s clients not to surrender their personal information to any entity that claims to be the bank and education of the bank’s clients not to trust any website simply because it holds the logo of the bank.

Banks have the obligation of ensuring the prevention of third-party processes which may lead to corruption and fraud through the customer privacy protections- banks have to do these through customer-friendly services. In any case, banks are not obliged or held accountable for the failure of customers towards the protection of their private data, including password/PIN. Expectedly, banks are compelled to conduct customer-contract reviews in terms of actualising protection of corrupt or fraudulent transactions. The developed contracts between banks and customers have to be:

- Easy to understand; written in a clear and concise language (in Arabic and English) that any customer will understand- it should avoid the ambiguous words or phrases; which may give rise to dual-meaning; also

- Based on clear statements on the liabilities of bank and customer in case of failure to meet their respective obligations.

Banks have to institute the development and execution of suitable education/ awareness programs concerning the product that they offer in order to create proper customer identification and authentication before the customers are given access to indulge in online-banking activities. Banks, in this regard, have at their disposal numerous outlets including websites, promotion-leaflets, printed-messages on customer-statements, as well as a direct-staff-communication via call-centres. The expectation is that advice given to enhance security should at least include such aspects as:

- Confidential use of Username and Password;

- Careful password selection to avoid password guessing; advise customers on how to select or create robust passwords or personal identification numbers that cannot easily be guessed or predicted;

- Appropriate storage of passwords;

- Adopt two-factor authentication based on SAMA circular no:40690 issued on 6th August 2009;

- Non-disclosure of personal information to unauthorised persons or doubtful websites/emails;

- Reminders not to access e-banking services through public or shared computers;

- Advise customers on how to identify the bank’s dealing official in case of “somebody” claims to be it; and

- Advise using the latest version of personal firewall and anti-virus.

Adding to the rules, banks have to make sure that they comply with other laws that link directly or indirectly with the ones emphasised. In order to outsource e-banking with regards to operations/activities, banks are obliged to be guided directly by, ‘SAMA’s Rules on Outsourcing’ – these rules are subjected to amendments periodically.

SAMA has continued to update these regulations in order to meet-up with globally acceptable processes/standards as well as the continually metamorphosing market environment. It is identified that ‘banks are expected to keep track of such changes and ensure compliance of the latest regulatory requirements’.

Application of Technology to Control of Corruptions and Fraud in Saudi Arabian Financial Institutions

Tech-driven fraud and corruption control in Saudi Arabia of late is fostered by online-banking which is creating a lot of opportunities that would enable the customer to benefit maximally from the variety of banking services available in the kingdom. Studies conducted recently on the reliability of technology towards enhancing customer usage of banking application and prevention of crime revived a high level of customer adaptations. It was realised that there is a drift from regular (or traditional) banking by customers to tech-driven banking.

On the contrary, the compliance of Saudi Arabian bank-customers was noted to be factored by easy and accessibility as provided by the banks. Specifically, online banking and its potential in controlling fraud and corruptions clearly remain one approach to be adopted for the prevention of corruptions/fraud within the banking system. Studies were conducted on the characteristics of online-banking users and a noted common assumption of demography which influences the acceptability of electronic self-servicing elements; which involves online-banking. The scholarly-work suggested youth are the most engaged in online-banking than adults/the elderly. The reason for this could possibly depend on the fact that youths are more interactive with computer devices, tools and services, and also feel the lesser threat in carrying out online transaction; as such they are more confident about deliveries from electronic services than older people. If this argument is anything to go by, it will be reasonable to suggest that the basic requirement for preventing corruption and fraud in bank-customers would be based on enhancing the confidence of the customer toward the development. Development of laws through corporate institutes must also be directed towards making the customer feel freer and more enabled to utilised financial products in the kingdom.

To emphasise, ‘youths actively seek out online banking tools, and they want to conduct all transactions through the same channel’. In any case, a related study brought about a different conclusion: Lee discovered that Customers-Relation-Management (CRM) is a particular factor of influence on the customer’s willingness to access online-banking self-services deliveries more than it could be noted of other factors on the subject. Findings showed that use of tech-driven banking facility in Saudi Arabia is attitude inclined rather than on demographics. Even if customers in the banking system are driven by CRM performances, it also amounts to ensuring that services delivered by banks must be articulately regulated by CFLs at all points in the system.

Related studies investigating exact implementations by CRM in the evaluation of criteria/problems which require tacking for success in the implementation of the CRM-program for enhancing the adaptability of customers to online banking were carried out by. The research was specified based on evaluation of the level of fraud and corruption experienced through the use of online-banking in terms of age of customer, and it was realised that people under the ages of forty are most likely to engage in corrupt and fraudulent acts in Saudi Arabia. There was hence the recommendation for the development of three-dimensional security-based web pages which had voice-recognition facility and used video tech.

Specifically, the outburst of new technologies in the banking world in recent years has brought about the variety of channels for carrying out banking services that are bringing to the barest minimal corruption and fraud such as the usage of Automatic-Teller-Machines (ATMS), internet-banking, and mobile-banking. It was noted from studies that, ‘…these technological interfaces are known as self-service technologies [SSTs]’. The customer has more opportunities for banking with the availability of SST facilities in terms of saving costs and energy. But the level of adaptation to the facility by customer varies or is a function of an individual’s perception or interest.

Equally, it has been affirmed that, ‘…although the kinds of service one can avail from these SSTs are similar, the patronage among the SSTs differs’. There is remarkable variation in the services offered by the various SST facilities and the level of acceptance by customers depending on the requirements for usage, benefits, perceived-risk, service’ nature or purpose.

In the UK, more than the situation in Saudi, the use of technology in banking service has proved to be effective especially in terms of bringing into effect CFLs as has been noted from literal works; this suggests that one best way to implement CFL in any financial system in present days has to be tech-driven as ‘the convergence of technologies has made the distribution of services more convenient than ever before’, as there are several options to the customer to carryout transactions at easy.

These technologies are designed to be user friendly or make the customer want to use them- because of the safety and reliability they offer. Saudi Arabia, like the United States and the UK, has been on a journey to make online banking more than just an interact-with-the-bank by customers, but a lifestyle of the customer to satisfy their financial transaction needs through safer legally regulated online banking technologies- such as paying for water and light rates. The Saudi Arabian banking system has so far made available online banking from retailing through Automatic-Teller-Machines (ATMs) and to some extent internet, and mobile phone devices. Hayek identified some benefits of retailing through SSTs to include cost-saving, energy-saving (and of course, enhancing better-appreciated application of CFL). In Saudi Arabia, it is not the entirety of provided services through SSTs that are made use of by customers, however. This has made the level of acceptance of online banking by the customer further a bit slower than in countries where there are several incorporations in SSTs.

The essence of using SSTs is essentially sectional and dependent on customer-services, transactions, Perceived-risk, as well as self-help. In the world of banking, services to customers are emphasised on high-quality deliveries. Perceived-risk (PR) has ordinarily been considered as a feeling of uncertainty which could erupt as a result of negative usage of products or services. It has been identified from studies that PR is of two dimensions structurally which are adversely consequent risks and light consequent.

Internet Banking in Saudi Arabia

Online banking in Saudi Arabia took off in the 1980s and has continued to grow steadily, creating new opportunities for banks to serve customers better and at the same time bringing about stiffer competition among banks. It has been noted with regards to recent developments with online/internet banking in Saudi Arabia that, ‘Saudi-banks are working together on shared e-system for conducting payments/authentication; because they have already cooperated through SAMA in developing shared payments systems and have established processes for future cooperation’.

SAMA has been on in Saudi Arabia for approximately thirty active years of intensive regulatory activities; during this period, it has laid the foundation for the contemporary system of payment through adherence to strict legal policies and effected laws which are setting new standards in the banking system of Saudi Arabia. During the year 1986, the agency brought into existence a system for automated clearing of cheques that made easy and allowed an effective interbank-settlement and cheque-clear. In any case, there are a lot of explanations to the non-flourishing of cheques as a channel for making payments and filling in the empty space; to overcome a number of emergent challenges, the banking stem adopted the usage of plastic cards in a rapid move. In recognition of the development, SAMA brought into existence the development of national-ATM-transactions switch which brought about linkage to the entirety of ATMs in the country thereby enabling the customer to easily get their details of accounts at any available banking unit located within Saudi Arabia.

According to Glan, ‘this system, known as the Saudi-Payments-Network (SPAN), went live in 1990, and was enhanced to support point-of-sale-transactions in 1993’. The expansion of SPAN-system was rapid so that in the year 1998, there was an interconnection of about one thousand six hundred ATMs as well as sixteen thousand points of sale-terminals which brought about the provision of all available access to an approximately three-million ATM-card owners who could access their services at any place in Saudi Arabia. Equally, within the ending of the 1980s, the agency brought into existence two fundamental initiatives including demand for the usage of swift-network regarding any transactions that had to do with international-payments, and then in the year 1990, the agency developed the electronic-security-information-system (ESIS). These were very laudable in furthering fast growth in the procedure for making payments within banking-systems in Saudi Arabia. More so, ‘this system, which had almost entirely dematerialised share-trading, achieves t+1 settlement as standards, and was soon to be moved to delivery vs Payment (DvP)’.

Even though these developments were in place, according to Brecht, ‘interbank settlements until early 1997, continued to be affected by cheque clearing or account transfer at SAMA’s head office and branches’. The development was attacked by whatsoever risk and inefficiencies that are known of with paper-based systems. Specifically, a demand for an electronic-funds-transfer (EFT) system was necessitated to allow for payments/settlements which involved various banks in an automated system- the development assumed a very significant point of support to payments systems within the kingdom. SAMA identified the necessity for the system to exist as a combination of the function of both a-high-value and a-high-volume system of payment which had to be the pillar a strategically making-payment in the future. Saudi Arabia protects online banking as has guarded by the Saudi-Payments-Network (SPAN) innovation.

Particularly, the control of corruption/fraud in the Saudi Arabian banking systems has become very effective through the regulation and control of financial inflow/outlet terminals, especially the Saudi-Arabian Riyal-Interbank Express (SARIE). There are many real and the possible merits of SARIE, but the most significant benefits to the banking system in terms of ensuring appropriate use of corporate financial laws are found below:

- Banks are now able to carry out electronic financial transactions which include receiving and transferring funds safely and securely through their SAMA account;

- It is possible to pay utility bills from anywhere without the client having to visit his bank;

- Funds could possibly be sent across the various banks in Saudi-Arabia without difficulty in an automatic way since the numerous banks are interconnected through the SARIE-device; and

- The SARIE-tool enables banks to give-out credit-facilities against a client’s accounts and transfers the money to the beneficiary’s account at any bank in Saudi-Arabia through Technology-Acceptance-Model.

The model is also one tool that has been found to be very applicable to a diverse dimension in information-technology and expresses cumulating traditions that are almost developed in any research. A lot of TAM investigations are known to be empirical and make use of surveying approaches which are capable of generating appreciable successes. For this study, the technology-acceptance-model is considerably a matured model which is made valid in several contexts. However, like the model, adapted by Gahtani, there is room for an empirical investigation of non-variance with the existent model through respondent-subgroups.

Online Service Quality Dimensions to Control of Corruptions and Fraud in Saudi Arabian Financial Institutions

Internet-banking offers a kind of self-service-technology that is fast assuming an important full-fledged allotment medium for utilisation of banking-products and banking-services, especially in developed countries. Seventy-three per cent of banks in Saudi-Arabia have web images, and at least twenty-five per cent are fully engaging the use of the services. The general increase in the usage of the internet recently has equally enhanced customers’ interest in e-Banking as preferred banking channel; except the interest of customers in online bank-services is being hampered by customers’ fear of losing personal bio-data against their personal security and privacy.

Within the banking circle, developing information technologically presents several effects of flexibility on payment methods and as well make banking-services more user-friendly to bank clients or customers. The relevance of controlling corruption/fraud through online-banking technology has been emphasized in several notable academic works.

The instance whereby banks make available customer-purposeful self-services is regarded as ‘transactional’ online-banking. Even though there are enormous derivatives from online-banking, it is very necessary for banks to take into cognisance the several risks that go along with it. Studies emphasised, even though the Saudi Arabian financial institution leads within the Saudi Arabian region, this leadership does not reflect a maximal utilization of technology.

This view has also been shared by Cartwright & Schoenberg. A very vital procedure which banks in Saudi Arabia have to adhere prior to carrying out any transformations has to be insured appropriate handling of online-banking risks. However, there are a number of complexities accrued to the determination of most accepted approaches by both banks and customers on the usage of online banking. Chau has identified distinct risks which are associated with the efforts of integrating fresh channels with the ones that are existent. Cockburn & Wilson, in their studies, have identified customers’ security/privacy concerns as being instrumental in enlarging the risks. The interest of the Saudi Arabian financial products user in adaptation to more secured technological models for the prohibition of corruption/fraud has been observed.

This suggests that corporate financial laws within the Saudi Arabian financial sector must be upgraded to reflect a sounder banking system in the best interest of the customer; especially as may be required for electronic commerce. To better understand how to monitor the interest of the customer to online banking in Saudi Arabia for developing a more appropriate CFL, Nachi considered instances from the United States where studies were conducted on ‘trust enhancers’. From the studies, it was found that the two basic items are relevant to the customer- which banks must always protect cautiously: these are financial-privacy and security.

The privacy of a customer to a bank could be said to be the individual’s fundamental right to provide personal information to a bank and control the level of exposure by which information is disseminated. In the banking world, concern about the privacy of the customer is no longer strange; even though banks may have a collection of information on their customers for long. In any case, the issue of customer-privacy has continued to stand out due to the emergence of fresh information-techs which usually are an improvement over previous ones.

A vast number of Saudi-Arabian banks have turned in for usage of electronic-banking with the integrated-approach whereby they maintain their brand-name and proffer electronic-banking-services options. These services are offered at low prices but are effective. As compared with other nationalities, Figure 5 shows net external assets of Saudi Arabia which has been prompt by the adaptation of technology in the Saudi Arabian financial institutions.

Other Options to Control of Corruptions and Fraud in Saudi Arabian Financial Institutions

The need for financial regulation must be seen as been beyond legislation or a code of conduct that may be obligatory; the regulating agency has to be responsible for enforcements as well. Basically, the regulation of corporate financial institutions is carried out following three basic principles, namely:

- Promotion of fairness, efficiency, and maintain an orderly market;

- Aid customers in retailing fair transactions; and

- Improvement of the capabilities of business and enhance the regulatory efficiency of a financial monitor.

A monitor of a financial institution or a regulatory body is typically responsible for regulating financial exchanges; financial service based markets, in-country industries and firms, as well as affecting standards which the financial institutions are expected to meet up with. The regulatory body has an authority to descend on non-compliance institutions or institutions that are lagging in meeting the laid down standards. This is where CFL becomes more effective in reinforcing the performance of CF institutions. In the United Kingdom, for instance, a body known as the Financial Service Authority has been empowered to conduct monetary activities as a finance regulator – this institution is what SAMA is to Saudi Arabia. Since it was established, the powers of the FSA have greatly increased, and its regulatory activities are pictorial over mortgage business and general insurance, from the period of November 2004 till date.

The efficiency OF performance of regulatory bodies is fostered by vast powers they are vested with for enforcing of rules. Particularly, this is the situation with finance service industry regulators who have the duty and powers to enforce rules over monetary bodies and ensure that principles are observed with a high degree of consistency for the benefit and interest of consuming society. A regulatory body will usually endeavour, assessing and scrutinising risk factors of firms or their activities and also ascertain the potentials of such to cause harm to consumers, market confidence, public awareness, as well as financial crime. Brosnan considers financial services as encompassing massive ranges of activities that involve finances and finance-management.

A financial industry service regulator is a saddle with the responsibility to keep the confidence of the public in financial systems afloat; this it does through strict| adherence to laws and rise of the understanding of the public about the state of regulated institutions, crime reduction and prevention, consumer protection, and fostering financial negotiations. However, it is impossible for a regulator to achieve one hundred per cent of regulation, due to inefficiencies and lapses that may be as a result of human/mechanical failures. A regulatory body usually has properly documented reports on the several micros of financial systems in a country and uses the same for recommending regulatory or legislative changes in cases of emergent loopholes in the systems.

And for the companies, it is the responsibility of senior management to ensure regulatory compliances and activeness of the business and cheek managerial risks and control which are viable to instituting organisational failure or system collapses. Ghung & Paynter have noted that the non-demanded subjection of the principle to intrusion by regulating authority which oversees transactions.

There are, certainly, confrontations to regulations which are tossed from international overlaps of financial markets and laws such as global economic crunches. It is pertinent for corporate financials regulators in particular countries to search for international cooperation with one-another to arrive at unified internationally accepted standards. The achievement of these by regulators must be ensured while an eye is focused on maintenance of vigorous competitions, cost minimisation for financial-institutions which comply with regulations, as well as consideration of innovations that can fire financial services on a good drive. A good example of how this is realised is regulation of financial services industries by FSAs where there is the supervision of deposits taken, exchange- monitor, investment- monitor, clearing-house monitor, as well as a monitor of other facets of financial industries.

In the USA, the expression ‘Corporate Financial Services’ gained popularity resultant from the Gramm-Leach-Bil-Act. It originated toward the end of the 1990s for the benefit merger of several kinds of firms which were functioning in the United States. Naturally, firms have two clear views on developing the business. According to Harran, a particular viewpoint is upheld as follows:

Companies usually have two distinct approaches: One approach would be a bank which simply buys an insurance company or an investment bank, keeps the original brands of the acquired firm, and adds the acquisition to its holding company simply to diversify its earnings. Outside the US (e.g., in Japan), non-financial services companies are permitted within the holding company. In this scenario, each company still looks independent and has its own customers.

On the other hand, corporate financial institutions may develop a self-owned brokerage barrier in an effort to market their products around their sphere of contact which has already been existent inceptively and utilise the combination of the totality of its products with a singular company. In this regards, corporate financial institutions tend to be known simply as ‘financial institutions’. The word ‘corporate’ is made use of to qualify such financial institutions from those which are known as ‘investment financial institutions’; a kind of entity which does not lend funds straight to businesses, but rather support in raising funds (called bonds or debts) and stock (also known as equity) from several other financial institutions. Primarily, financial institutions (particularly the banking subsector) do the following activities:

- They help safe-keep money as well as permit withdrawer of the money in times when the saver needs same;

- They issue chequebooks for usage in payment or settling of bills as well as enable the delivery of other payments through postage;

- Grant loans;

- Issue credit cards as well as process same;

- Issue debit cards which are used instead of chequebooks;

- Issue ATM cards and provide the machinery for its usage throughout its jurisdiction.

- Carry out wire transfer services for individuals through banks;

- Supports retention of order for easy payment of bills automatically;

- Grant overdraft permissions temporarily for the growth of funds of the bank to catch up with expenses which are incurred every month; and

- Carry deal with the likes as may be provisionally authorised.

Other Types of Bank Services Regulated by FSA

Other banks regulated by the FSA include:

Private Banks: these are banks that offer their services to limited or specify worthy individuals. In this case, an individual or a family must have a certain net worth for the service to be given the same. It is more known of this kind of banks to give personal services than it is the case with the day to day retail banks.

Capital Market Banks: these are shouldered with responsibilities for underwriting outstanding amounts and equities, and supplementing the businesses of companies as well as helping out in restructuring of debts into monetary products which are prearranged.

FSA also regulate the following:

Foreign exchange services: These services are carried out by a lot of banks all over the world, and they basically include the following as stated by Belanger et al.:

- ‘Currency Exchange – where clients can purchase and sell foreign currency banknotes.

- Wire transfer – where clients can send funds to international banks abroad.

- Foreign Currency Banking- banking transactions are done in foreign currency’.

Investment (through banking) services:

- Asset management. This expression normally presents an instance where a company is run on collectively invested funds. It also means the provision of services by another institution which has registered adequately and regarded as an investment advisor.

- Hedge Fund Management- this normally has the responsibility to provide ‘prime brokerage’ services at notable investment banks for conducting marketing.

- Custody services-this comprises the provision of securities as well as offering other functions that are collectively allied.

Insurance:

- Insurance brokerage- this ensures shopping for insurance (which in general are related to property) in customers’ proxy. Lately, several internet sites are developed to deliver to customers defined prices in comparison to such services as insurance which has resulted in the conflict in the sector.

- Reinsurance – this has to do with selling insurance to the institutions which are responsible for selling insurances in order to secure them from hazardous losses.

An effort to enhance a corporate financial institution that can be competitive and effective in a country such as Saudi Arabia which will enable financial institutions to generate financial markets that will be of high quality and which will meet the demands of consumers could pose a huge challenge without appropriate adaptation of corporate finance law. For instance, the Japanese market has been caught in this web of difficulties. This has necessitated the need for improvement of corporate financial law and proper regulation of business environments to suite users and subsequently, corporate financial institutions. In this consideration, the FSA in Japan has made significant efforts to attain enhanced regulations by the presentation of a concept known as Optimal Combination of Rules-Based and Principles-Based Supervisory approaches, and has had diplomatic chats with concerned financial institution representatives on significant strategies that are utilisable for the effectiveness of principle-based supervisions. The FSA has hence accepted to cooperate and work in partnership with relevant stakeholders. Dishaw & Strong have stated that:

The “Principles” are a set of key codes of conduct or general behavioural rules that are the underlying basis of statutory rules such as laws and regulations and should be respected when corporate financial institutions conduct their business as well as when the FSA takes supervisory actions.

The supervision which is principle-based is a mechanism which agrees with principled discussed; which have emphasised encouragement of efforts made by financial institutions in the improvement of self-initiative business management. In the assemblage of the principles, FSA had conducted several symposiums for idea-based interactions with several stakeholders in economy control.

FSA has also had talks with individuals in an effort to share unified views with regard to the principles in order to actualise the following:

- To enable users to acquire pre-hand knowledge on market trends and have adequate consideration of the quality of services offered by finance services, conceding conscious alertness to security, and

- To give clear visionary pictures to financial service providers regarding what actions they could take in instances where there is no stipulated or lay down rules or where there is a lack of interpretation of ones that are existent.

A framework for supervision and regulation of the banking sector in the United States is carried out through Acts which foresee monetary activities, including the activities for exchange control, Banking Act, and the Act of monetary laws. The Central bank is concerned with the issuance of licenses to banks in two groupings; including Licensed Specialized Banks (which are responsible for savings and developmental functions) and Commercial banks. The major variation between the two categories of banks is that commercial banks are allowed to admit public deposits through the operation of current customer accounts and is also authorised to deal in foreign exchange. This entitles the bank to be involved in wide-ranges of foreign-exchange-transactions. These functions are not identified with specialised banks. The distinct variation with the Saudi Arabian corporate financial sector and the US, in terms of the banking subsector are based on Saudi Arabia’s limitation to Islamic banking which at the moment gives almost all banks the right to operate under corporate Islamic banking laws. In the US, the central bank is empowered by law to carry out the following:

- Granting of approvals for the establishment and closure of bank’s business outlets, bank branches as well as the entire bank;

- Issuance of prudent directives, orders and determinations to banks, statutorily; and

- Conducting of onsite and offsite examining of banks as well as enforcing of regulations and resuscitation of feeble banks.

The supervisory and regulatory licensing function of the central bank is overseen by the supervisory department of the bank. Bank supervisions as carried out by the Central Bank are footed on standards which are agreed upon worldwide through the commitment of a bank supervisory committee known as Basel Committee.

With regard to the banking act provisions and the financial law act, the several commercial banks are licensed, and equal license is granted specialised banks which are answerable to examinations which are statutory in nature, at least once in two years. A fresh onsite monitory way which utilises the process of examination and which focuses on specifying risks identifiable with banks and properly curtailing such risk through effective managerial strategies as well as assessing of adequate resources for mitigating such risks is considered recently. This is supported by an examination-based worldwide model, known as CAMEL. CAMEL is derived from the terms capital adequacy, asset quality, management, earnings and liquidity.

Additionally, the compliance to laws and other statutory requirements by financial institutions (banks in specific) and the control of standards which are corporate-government related is emphasized. Situations of non-compliance to sensitive requirements and indications of flaws or any identifiable deficiencies in the state of finance and systematic controls of banks are directed to the attention of a directorate board by the corporate financial institution the kingdom in insurance affecting necessary actions.

But general, enhancing corporate financial institutions’ performance through corporate laws is becoming a global affair; for example, the G20 has spearheaded the invention of stiffer and more worldwide-monitored regulations of FSAs, recently. This is done with particular attention directed in identifying and managing risks which may develop systematically, and transpire trade incentives and also ensure protection to customers in order to enhance resolutions and recoveries. Well defined internationally accepted incentives like the Basel-Accords (Basel III) upgrade has been structure to bring about better financial institution stability through improved capitalistic requirements as well as liquidity rules.

In the UK and the USA, particular regulatory metamorphosis is noted in the planning and implementation regarding financial regulations in accordance with G20’s recommendation. Emphatically, in the United States, the legislation by Dodd-Frank offers a fascinating mechanism which has ruled most of the recommendable amendments found with regulations of FS. In the UK, Europe to be specific, fresh bank, insurance, and asset managing ‘super-regulators’ are brought up from previous national regulatory committees.

The corporate financial institution in Saudi Arabia in recent times is considering slender compliances at how to bring about developments that will alternate or bring out the attraction of operative models. The major reflections take into account effective identifications and control of risk. Thus for SAMA, which is a regulator of financial institutions, the practice of regulation is necessary to project accessibility and tackle the definite, operational and fresh regulative compliant implications.

A number of recommendations were suggested by the European Commission regarding finance-sectored payments for the achievement of fundamental development. According to the suggestion, states which are members and boun by the regulations of FSA had to make sure that their financial institutions generate remuneration strategies which would minimise risk which affect staffs with impeccable consistency records and who facilitate fantastic and efficient risk-reduced managements. The recommendation brought about clear outlines on payment structure, on engineered processes and on fostering completion of remunerative procedures as well as on the improvement of supervisory roles of authorities toward reviewing of policies on finance institutional remuneration. The commission thus recommended the policy for effective management. This recommendation is considered here to be effective when applied to the Saudi Arabian corporate finance.

Similarly, in effect to attain regulatory stability, McCreevy- who was a commissioner of Internal-Market expressed the view that ‘an increased role of supervisory authorities in the review of remuneration practices is also needed to promote sound remuneration practices in financial institutions’. It was recommended to participating states to ensure the usefulness of the following:

Payment structure: there should be conscious of risking by staff members on policies, and this should be observed with a high level of consistency and deliberate effort to bring about laudable promotions as well as enable to manage risks effectively. In this regard, corporate institutions that are shouldered with responsibilities of handling finances should place clear balances between payments and bonuses.

The payment of the major part of the bonus should be deferred in order to take into account risks linked to the underlying performance through the business cycle. Performance measurement criteria should be a privilege of longer-term performance of financial institutions and adjust the underlying performance for risk, cost of capital and liquidity.

Corporate financial institutions in Saudi Arabia, by the suggestion, are expected to have the potential of reclaiming bonuses paid in case records indicate a misstated manifestation or claw-back. This is necessary for the actualisation of the following:

- Governance: policies on remuneration are expected express transparency within the internal system. Such policies should be document adequate contents through a measure that avoids conflict of interest. A board is expected to be capable of overseeing remunerative operations as regarding the totality of financial institutions which is properly controlled through functional tools and through effective utilisations of human resources.

- Disclosure: these policies are expected to disclose adequate information to stakeholders. The disclosed information is expected to be as clear as possible, and should also be easy to understand.

- Supervision: supervision should be ensured with the use of sophisticated supervisory mechanism within their reach of the institutions and should be applicable to laudable remunerative polices. As an effort to curtail issues which may emerge from proportionality, it is adviced that supervision should be done considering the state and statue of the financial institution in question as well as consider the complex nature of activities as an effort to assessing total compliance with existent principles.

The recommendation has appropriately considered effort which is already put in place by the various members and aims of SAMA at promoting development through the identification of practices which best address the issue of unity of the Saudi Arabian financial sector. The recommendations stretch to the several sectors of SAMA as an effort to prohibit collusive factors and bring about the prevention of competitive distortion among the various wings of the financial institutions. The principle is utilisable to the totality of the staffs with impactful activities on the handling of risk. In a similar study to this, Brecht who also came about the same recommendation, noted that ‘the Recommendation will be followed up by legislative proposals to bring remuneration schemes within the scope of prudential oversight’.

The Saudi Arabian finance marketing service has also taken notice of the basic function adopted by finance service marketers in making decisions and has a searchlight beamed on the basic kinds of decisions-as well as problems- which face activities of marketing through continuous reviews of their documents. This point of view has been supported by Ghung & Paynter, who have emphasised retouch of documentation in the following words, ‘the reviews should be made more accessible and include gripping case studies to demonstrate the realities of financial services marketing in an unstable and competitive environment’.

Regulation of finances of a monetary institution has been considered in this paper to be a conscious effort to ensure proper adherence to specified requirements, guidelines, and boundaries that are set with an expectation to keep the financial institution reliable and functional as well as rejuvenate the regulation which could be done through legislation or a code of conduct that may be obligatory.

Problem Discussion

The need to instrument the confidence of stakeholders in the financial sector through corporate financial law in Saudi Arabia is necessitated by a corresponding need to bring about faster, better and more efficient financial sector in the kingdom. As an Indicator for accessing the effectiveness of CFL in Saudi Arabia, online banking is known to make available opportunities for banking with the availability of SST facilities in terms of saving costs, energy and time. However, the level of adaptation to the various facilities by customer varies as a function of individual-customers’ perception or interest. Generally, there is distrust by customers in the ability of the financial sector to secure the information or bio-data of customers, particularly in the online banking system.

Equally, there is remarkable variation in the services offered by the various SST facilities and the level of acceptance by customers depending on the requirements for usage, benefits, perceived-risk, service’ nature or purpose. For CFL to be fully effective in Saudi Arabia, it must be designed to embed recently technologies that promote user friendly or make the customer want to use them based on the extent of security they offer. Saudi Arabia, however, is on a journey to make the best of CFL, especially by making online banking more than just an interact-with-the-bank by customers, but a lifestyle of the customer to satisfy their needs. The Saudi Arabian banking subsector has so far made available online banking from retailing through ATMs and to some extent internet, and mobile phone devices.

Aim and Objectives

The aim of implementing corporate financial law in Saudi Arabia is to bring about fortification of transactions both internal and external against corrupt and fraudulent acts and as such ensure an easy, faster, and cheaper means of benefiting from corporate financial institutions.

Methodology

One scaling method that is found very useful in qualitative research Analysis where questions are asked for evaluation certainty of data is the General Linear Model (or the GLM) which is a tool that is used to effectively incorporate the normal distribution of dependent variables as well as variables that are continuously independent. The GLM procedures afford one the opportunity to operate with specifically generalized linear models in terms of syntactic or dialoguing boxes, and equally makes it possible for one to get outcomes in a pivoted tabular format- this is of considerable significance based on the fact that the GLM makes easy the editing of outcomes.

Otherwise, the several features present on the GLM, therefore, make it possible and easier for one to put together designs that have vacant cells by plotting mean estimations and customizing linearly structured models in conformity with an available research question. The research question in this regard is to evaluate how corporate finance law has been used as an effective tool for elimination of corruptions and fraud in Saudi Arabian financial institutions. Been conversant with fitting linearly structured models, univariate, multivariate or recurring measures, the researchers, therefore, find useful the GLM procedures. Basic GLM features including sum-of-the-square, estimated-marginal-means, profile plots, as well as custom-hypothesis tests which are optional in 4 approachable measures and are well structured for the evaluation of sums-of-squares (SS). These SS options are quite easy to access. The first type of SS enables the calculation of reduced error SSs through the addition of effects in the model periodically.

The use of multivariate methods in conducting surveying measurements by researchers has proved to be vital in analyzing index constructions as well as in exploring initial-stage data that has specified surveyed subdivisions. With a good understanding of multivariate methods of sampling, one will certainly appreciate the significance of using such in the determination of index constructions in a very practical angle of consideration. For an evaluation of the effectiveness of corporate financial laws in addressing corruption and fraud in Saudi Arabia, the study, therefore, uses analysis of the hypothesis that the application of CFL to Saudi Arabia’s corporate financial institution needs to be strength- this is developed from hypothetical analysis as shown in Appendix ‘D’.

Findings And Analysis

Demographic Findings and Analysis

Demographic findings on the effectiveness of corporate financial laws in addressing corruption and fraud in Saudi Arabian financial institutions reviewed that there may be the following challenges:

- Recognizing and solving problems of customer concerns on transactions;

- Building and maintaining the confidence of clients;

- Enhancing clients’ inexperience; and

- Convincing clients to accept the impact of secure corporate financial transactions;

The Saudi Arabian corporate financial institution can prevail over the above challenges by applying the following two strategies:

- Disclosing risks to customers of the financial institution;

- enacting more friendly and tech-driven laws, and

- Educating customers.

Saudi Arabian financial institutions should make accessible, clear information to clients on the demerits and merits of services offered by the various institutions; this could be actualized through the publishing of consumer privacy and protection policy, disagreement handling, reporting and problem resolution procedures, etc. Saudi Arabian financial institutions should inform their customers that proper security measures have been set up to guarantee the safety of their funds. Corporate financial law also needs to highlight the type of encryption and firewalls used to ensure safety. The prevalence of corporate financial law in Saudi Arabian financial institutions is also dependent on problem stemming, particularly from unbalanced information.

Reliability

It is rare for corporate financial laws to survive in this twenty-first century without consideration of independent-investors- who cut across different countries and firms. In most cases, in enacting such laws, there is also the need to consider the venture-capital-market. Venture-capital businesses make available finances to host nations in the area like technological-designs, financial projects and legal matters which bring about ample chances to save the rights of financiers and help government agencies to be strengthened. Businesses achieve more international recognition and expertise, which can easily conquer any setbacks that may be experienced. Venture-capital in an international business has to do with investment-organizations coming together financially to protect the interest of a company.

Responsiveness

From the demographic findings on the effectiveness of corporate financial laws in addressing corruption and fraud in Saudi Arabian financial institutions, the responsiveness of corporate financial laws demands an interlink of the various financial units under the control of the corporate finance institution so that there could be the collecting funds from various sources and looking out for different firms worldwide who are in dare need of capital to advance their newly established business. After financial commitment in all these companies, Saudi Arabian financial institutions in returns would get an equitable share from such firms and enjoy more dividends if the firms do better in the business environment. Studies have reviewed that financial institutions are the best place to access fund for established firms.

Fulfillment

It is argued that based on the high rise in the internationalisation of business, a lot of the freshly established firms which lack the know-how that investor really wants may enjoy the open hands of venture-capital firms Which’s assistance provides unquantifiable benefit to all investors worldwide. Banks are sometimes not that readily positioned to assist fresh establishments; not because the funds are not available but for information lop-sidedness and overhead cost. Venture-capitalist is stronger in this type of business by engaging in effective monitoring and personal contracting.

In the United States, venture-capital is appreciated as an economic hub which embraces difference industries. Venture finance is not a long period transaction, but only cherished investment in an organisation with a good balance-sheet and well-positioned infrastructural capabilities are the bases for future acquisition to any public institution. Venture-capitalists acquire parts of any entrepreneur capital and build it within a specific period to grow and later dispose of it with the assistance of an investment banker. Usury laws which allow a reduction in what banks charge on interest base on the money borrowed funds and any danger that may be witness come into play.

Even though personal equity and VC funds are fairly small worldwide, several nations still record high-growth-level in this business. Some years back personal equity fund moves up to forty-five per cent in India, while China republic was three hundred and twenty-eight per cent. Facts behind this advancement in VC activities in China can be traced to result-oriented-formation and good host nation policies to defend funds. Any country with political stability will definitely win the heart of venture-capital-organisation, and a couple of other factors mentions earlier, which allow firmness in policy, there is a good location for the investor without any iota of doubt.

It should be known that investment from another country creates ample of opportunities to the investors of such funds; these privileges can be in the form of a free-tax-holiday, fast approval of business documents, easy recognition and patronage by policymakers to all the foreign investors. Again the host nation gains a lot in this kind of international investment environment which drive growth economically by creating jobs, improving on expertise, raising the proper standard of living for the citizenry. Now it is known that every party that involves itself into international business, especially the host nation benefits immensely from such an opportunity. Host nations to this kind of direct investment need to develop articulate policies that can drive more investment which can boost the national economy in a positive direction. For some nations, caution needs to be taken in tax collections. This is a sensitive field that a professional needs to be consulted and possibly propose a total reduction in investment-tax, which can really encourage the influx of foreign investor to the nation.

Privacy

Today’s awareness of technology-based economy encourages Saudi Arabian financial institutions to look out for substantial assets in getting loans which only a few have such assets to give as a standing order. Most of these Saudi Arabian financial institutions are guided by law to safeguard public investment, and again such law allows an organisation to get access to the public market.

Analysis

Socio-technical systems (STSs) constitute tools which are made use of in helping IT-based management to succeed in resolving corruption and fraud. The need to effectively utilise the fundamentals of STSs makes socio-technical-analysis readily available as a facility for the integration of social values and ethics in the management of financial institutions. In other words, the psychoanalysis of socio-technical systems enables a better comprehension of social-impacts and aspects of ethics of financial institutions; and basically, there is the enablement to diagnose and curtail appropriately anticipated probable challenges.

This study has been based on utilising STS tools in for enhancing the workability of corporate financial law in Saudi Arabian financial institutions through the following fundamental key points, among others: