Introduction

The study of available information on chemical elements allows systematizing the existing knowledge and immersing the study of chemical diversity. It is essential to note that the study of the element must be complex and multifactorial, reflecting not only the technical information about the chemical and physical properties but also the history of discovery, details of use, and geographic location on the planet. All this allows to collect and organize fragments of research, knowledge, and articles about the chemical element, and thus, this is a good practice for learning. This research paper’s object was chosen silicon element, which is one of the most common materials in the Earth’s crust. This work will discuss the history of its study, the names of the discoverers, some of the most impressive physical, chemical, and biological properties of silicon, as well as the richest deposits.

History of Discovery

As a chemical element, silicon has existed on planet Earth since the celestial object’s birth, but its research discovery came much later. Given that most meteorites are rich in silicon compounds, one can assume that this material came to the planet due to bombardment during the early stages of the chemical world (Komatsu et al., 2018). The French scientist and father of modern chemistry, Antoine Lavoisier, unsuccessfully tried to isolate pure silicon from the sample of silicon dioxide, and later, in 1808, English chemist Humphry Davy gave the material the Latin name “silicium” (“Silicon,” n.d.). It took three years before Gay-Lussac and Thénard were able to obtain separated silicon by passing on vapors of silicon fluoride, SiF4, over boiling potassium (Eq. 1). Nevertheless, the discoverer of the element is considered a famous Swedish mineralogist Jacob Berzelius, who first received pure silicon in 1823. Since then, the study of the material has deepened, and by 1854 the world community learned about the shape of the crystal lattice of the element: it is atomic.

SiF4 + 4K → 4KF + Si

Physical and Chemical Properties of the Element

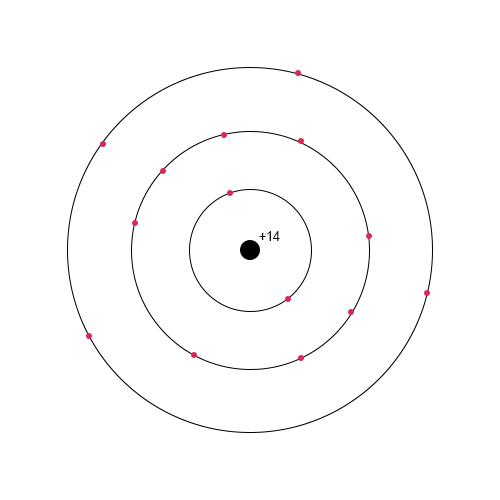

A discussion of the chemical and physical properties of material should precede an investigation of how the material is used since understanding what molecular interactions a material has in combination with how it reacts with the environment determines its potential for application. The electronic configuration of silicon is such that on the third energy layer, it contains four electrons, which dictates a ban on higher valences than IV (Fig. 1). Thus, silicon can be both an oxidizer and a reducer, as can be seen in Eqs. 2 and 3. Although silicon dioxide is extremely common, direct interaction between two nonmetals in nature is unlikely since a reaction requires a temperature of 400 °C.

In terms of physical properties, silicon can be confusing because it has atypical metallic properties. In particular, silicon, being a non-metal, looks like a shiny hard sample, as illustrated in Fig. 2. In this case, the material is quite brittle and crumbly, it has a melting point of 1410 ° C, which is half as low as that of iron (“Iron,” 2019). Silicon is a good semiconductor and conducts electric current better than rubber: while increasing the medium’s temperature, the ability of the material to conduct current increases.

In Nature

It is essential to say that silicon practically does not occur in its native form but can be found as dioxide and silicates associated with various metals. Silicon dioxide synthesized in nature is typically found in quartz — especially in the sand and many stones — although this is not the only modification of the material: crystallite, coesite, and tridymite have also been found in the crust. There are differences in the amount of silicon in the Earth’s crust, but this number traditionally exceeds 27%, making it the second most common material after oxygen (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2020). Although the element is widespread, the largest amount of silicon (about 2/3) is traditionally mined in China (Garside, 2020). In addition, silicon is produced in Russia, Norway, and the US.

Meanwhile, silicon content can be found in the human body. Elemental silicon plays a vital role in cross-linking collagen proteins, making it necessary materials for the normal functioning of cartilages, bones, and joints (“Silicon – Biological role,” 2016). Moreover, silicon lining the walls of blood vessels includes the aorta, arteries, and trachea. However, silicon can hurt humans: silica, SiO2, is toxic to the respiratory system, causing chronic respiratory diseases, and even cancer (Bass, 2017). For this reason, human interaction with silicon dioxide crystalline should be limited.

The Uses of Silicon and its Isotopes

In nature, there are a large number of silicon isotopes, which find their application in different fields. Thus, silicon has more than 24 known isotopes, of which only three are thermodynamically stable (their percentage is shown in Fig. 3). It should be recognized that most isotopes are used for scientific purposes: to determine chemical processes of the early universe, to analyze the development of the solar system, and to weather silicate rocks (André & Cardina, 2018). The application of the most common silicon isotope, 28Si, is significant for humanity. Thus, silicon is used in low-tech products such as bricks, artificial clay, ceramics, and high-tech solutions: transistors are applied everywhere, from radio to iPhones. Moreover, some silicates can be found in cosmetics where they are needed to dehydrate the material and create a protective matrix. Thus, silicon shows a vast range of uses in everyday life.

References

André, L. & Cardina, D. (2018). Silicon isotopes. Springer Link.

Bass, H. (2017). What is silica and why is it dangerous? Concentra.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2020). Silicon. Britannica.

Garside, M. (2020). Silicon — Statistics & facts. Statista.

Iron – Melting point – Boiling point. (2019). Nuclear Power.

Komatsu, M., Fagan, T. J., Krot, A. N., Nagashima, K., Petaev, M. I., Kimura, M., & Yamaguchi, A. (2018). The first evidence for silica condensation within the solar protoplanetary disk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(29), 7497-7502.

Shahar, A. (2016). Silicon isotopes. Springer Link.

Silicon. (n.d.). Periodic Table.

Silicon — Biological role. (2016). MineraVita. Web.