Abstract

This study aims to assess how group membership with perpetrators affects empathy towards the victim and moral justification towards the perpetrators’ actions among Malaysian citizens. A between-group experimental study was conducted virtually in which the participants answered an online questionnaire. In this study, the independent variable of group membership with the perpetrator was be manipulated by giving 52 participants the Malaysian abusing a foreign maid article while the other 53 participants read a non-Malaysian abusing a foreign maid article. Next, the dependent variable, empathy for the victim, was measured using Batson et al. ‘s (1997) empathy scale. An adapted version of Tarrant et al. ‘s (2012) scale measured the perpetrator’s actions’ moral justification. Due to in-group and out-group biases, the present study established that the empathy was statistically significantly higher for victim in Malaysian article (M = 5.128, SD = 1.072) than in non-Malaysian article (M = 4.343, SD = 1.458), t(103) = 3.14, p = 0.002. In contrast, the difference in means of moral justification is not statistically significant between Malaysian perpetrator (M = 5.414, SD = 0.894) and non-Malaysian perpetrator (M = 5.486, SD = 0.928), t(103) = -0.407, p = 0.685. In conclusion, participants had biased empathy for victims according to social identity theory, but they had a similar level of moral justification.

Keywords: group membership, empathy, moral justification

Introduction

According to Tan (2011), in the year 2006, there were a total of 310,661 foreign maids working in Malaysia. Unfortunately, some of them have been exposed to various abuse by their employers (Tan, 2011). One infamous maid abuse case is of Suyanti; a 19-year-old in the year 2016, an Indonesian maid who was beaten with numerous items, in which the Malaysian employer was eventually sentenced to eight years in jail (Mokhtar, 2018). Moreover, a 2018 case of a 21-year-old-Indonesian-maid Adelina Lisao died due to multiple wounds and multiple organ failures caused by the inhumane treatment of her Malaysian employer (The Star, 2019). These maid abuse cases and many more have led to Indonesia threatening to ban maids coming to Malaysia, yet not much has been done to solve this issue (The Straits Times, 2018).

How do Malaysians attribute the horrendous acts committed by their fellow Malaysians? According to Hogg (2016), social identity theory focuses on intergroup relations which analyses the issue of conflict and cooperation between big social categories. Social identity is the individual’s perception of how others would treat and think of them. Intrinsically, people want others to treat them favourably. Thus, when people compare their group (ingroup) with an out-group they would ensure that their group is viewed more distinctively and positively (Hogg, 2016).

This is supported by Lee and Ottati (2002) who found that the Mexican participants (ingroup) were more willing to grant privileges to an illegal Mexican immigrant and his children compared to their US counterparts (out-group). This suggests that people from the same nationality would treat members of their group more favourably. Furthermore, Bocian and Wojciszke (2014) found that having a positive attitude towards a perpetrator would increase the likelihood of being biased and making overly positive impressions of the perpetrator’s behaviour despite it being immoral. Thus, a positive attitude that is formed due to having similar social identities with the perpetrator could lead to morally justifying an immoral act.

Next, Tarrant et al. (2012) found that torture perpetrated by an ingroup was more morally justified by the participants than when torture was perpetrated by another group. Despite torture being universally understood as a human rights violation, this study has demonstrated that people would justify it when their social identity is involved. The study also proved that empathy is shaped by social identity whereby participants are less likely to empathize with a torture victim perpetrated by the ingroup to justify the behaviour and protect the ingroup. However, the study lacked replicability as it did not cite the scale used to measure moral justification as well as used only Western participants which consisted of American and British citizens (Tarrant et al., 2012).

Due to different cultural backgrounds, results may differ if replicated in an Asian setting (Servaes, 2000). In which, the present study will focus on perceptions of maid abuse, which is prevalent in our society (Tan, 2011). Therefore, the current study aims to assess how group membership with perpetrators affects empathy towards the victim and moral justification towards the perpetrators’ actions among Malaysian citizens. In which a social group is defined as more than two interdependent people (Reicher, 1982), empathy is defined as an emotional response towards another regarding their perceived welfare (Batson et al., 2002) and moral justification is described as denying or decreasing the obvious negative aspects of action (McGraw, 1998). We hypothesized that the empathy score for the victim will be lower and the moral justification score for the perpetrator will be higher if the perpetrator belongs to the same ingroup based on the social identity theory.

Methods

Participants

The current study will recruit 105 Malaysian citizens, both male and female above the age of 18, but excluding participants taking or have taken social psychology as a subject. Due to the Movement Control Order, we will collect data from participants through online questionnaires. We will be using a convenience sampling method as participants will be recruited through close Malaysian friends and family, and social media. Fifty-two (52) participants will be given an adapted article about maid abuse with Malaysian perpetrators while the other 53 will read about the Non-Malaysian perpetrator (Huang & Yeoh, 2007). All participants will be randomly assigned to the different groups. Due to ethnicity being a possible confounding variable, the ethnicity of both the employer and maid were excluded from the article.

Measures

Participants’ empathy towards the victim will be measured using Batson et al. ‘s (1997) empathy scale. Six emotional states, which are sympathetic, compassionate, soft-hearted, warm, tender and moved, are assessed in the measure. The measure utilizes a 7-point Likert scale where “1” is “not at all” and “7” is “extremely”. The higher the empathy score, the more the participant empathizes with the victim. The empathy scale has a high level of reliability, α=.91. Furthermore, the moral justification questionnaire from Tarrant et al. (2012) will be adapted to measure the moral justification of the perpetrator’s actions. This measure utilizes a 7-point Likert scale where “1” being “not at all” to “7” being “extremely”. Among the four items, only one item is reverse-scored. This measure has high reliability, α=.83. The higher the score of moral justification, the more the participants believe that the act was justified.

Procedure

Firstly, an information sheet containing information about the experiment will be provided to the participants, followed by a consent form. Then, we will gather demographic information of the participants before randomly assigning them to read an article about maid abuse with a Malaysian perpetrator or a Non-Malaysian perpetrator. Next, the participants will be asked to complete the empathy scale and moral justification scale to assess their empathy for the victim and moral justification of the perpetrator’s behaviour. Lastly, a debriefing form will be provided at the end of the research.

Research Design and Proposed Analysis

This study is a between-subjects experiment. The independent variable is group membership with perpetrator which is categorical, whereas the dependent variables; empathy for the victim and moral justification of the perpetrator’s action, are both continuous. A between-group study design will be used as two groups of participants will be exposed to different conditions, which are the Malaysian perpetrator article and the Non-Malaysian-perpetrator article. Moreover, an independent sample t-test will be conducted to compare the means of empathy for the victim and the moral justification of the perpetrator’s actions between the group who are in the ingroup with the perpetrator and those who are not.

Results

Demographics

The analysis of gender shows that out of 105 respondents, males formed the majority group of 53.3% (n = 56) while females constituted the minority group of 46.7% (n = 49) (Table 1).

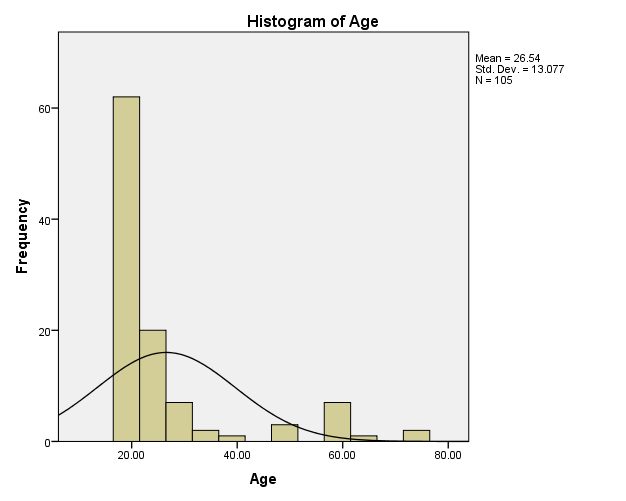

Descriptive statistics of age (Table 2) reveal that respondents have a mean of 26.54, a mode of 20, and a median of 21. The dispersion of age is high because it has a maximum of 72 years and a minimum of 19 years with a standard deviation of 13.08, a variance of 171.00, and a range of 53. The distribution exhibit a high degree of positive skewness (2.216) and positive kurtosis (3.717) (Table 2 and Figure 1).

According to Table 3, the proportions of responses to Malaysian and non-Malaysian perpetrators were almost the same, with 49.5% (n = 52) and 50.5% (n = 53), respectively.

Regarding the experience of having a maid, 52.4% (n = 55) stated that they have had a maid in their households while the remaining 47.6% (n = 50) indicated that they have not had a maid in their families.

Empathy for Victim

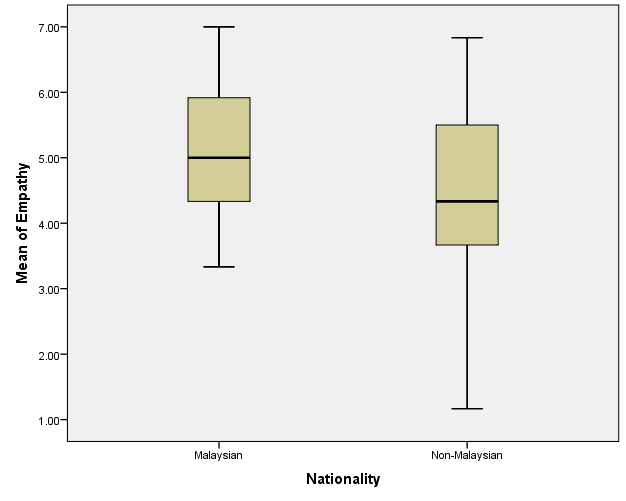

Table 5 shows descriptive statistics of empathy scores for victims by nationality of perpetrators. In the Malaysian perpetrator’s article, the empathy score has a mean of 5.128 and a median of 5.000. The empathy score has a high level of dispersion because it has a variance of 1.149, a standard deviation of 1.072, and a range of 3.670. The distribution reveals that empathy has a positive skew of 0.259 and a negative kurtosis of -0.947. Comparatively, the empathy score due to the non-Malaysian perpetrator’s article has a lower mean of 4.343 and a similar median of 5.000. The dispersion of empathy score is high in response to non-Malaysian perpetrators’ articles because the range is 5.670, the variance is 2.127, and the standard deviation of 1.458. The distribution of empathy score has a negative skew of -0.373 and a kurtosis of -0.470.

The boxplot below (Figure 2) depicts that Malaysians have a higher mean of empathy than non-Malaysians. However, the dispersion of empathy scores among Malaysians is lower than among non-Malaysians.

Group statistics indicated that the mean of empathy among Malaysians (M = 5.13, SD = 1.07) is higher than among non-Malaysians (M = 4.34, SD = 1.46) (Table 6).

Independent samples t-test showed that the difference in empathy scores between Malaysians and non-Malaysians is statistically significant, t(103) = 3.14, p = 0.002. Therefore, the test rejects the null hypothesis that respondents have a similar degree of sympathy for victims of Malaysian and non-Malaysian perpetrators.

Moral Justification of Perpetrator’s Actions

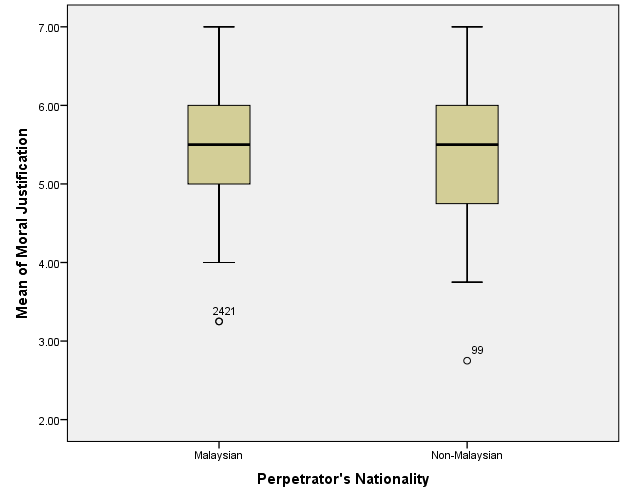

Descriptive statistics (Table 8) show that the moral justification of the Malaysian perpetrator’s actions has a mean of 5.414 and a median of 5.500. The moral justification’s dispersion is low since the standard deviation is 0.89, the variance is 0.799, and the range is 3.750. The distribution has a negative skew of -0.281 and a positive kurtosis of 0.138. The moral justification of non-Malaysian perpetrators’ actions has a similar mean of 5.486 and a median of 5.500. With the variance is 0.862, a standard deviation of 0.928, and a range of 4.25, the variation of data is low. The distribution of data has a negative skew of -0.310 and a positive kurtosis of 0.250.

Figure 3 shows that the moral justification of actions has similar means and distributions for both Malaysian and non-Malaysian perpetrators.

Comparison of means reveals that the moral justification of actions is almost the same in Malaysian perpetrator (M = 5.414, SD = 0.894) and non-Malaysian perpetrator (M = 5.486, SD = 0.928) (Table 9).

Independent samples t-test indicates that the difference in means of moral justification is not statistically significant between the Malaysian perpetrator and non-Malaysian perpetrator, t(103) = -0.407, p = 0.685. Thus, the findings fail to reject the null hypothesis that moral justification is the same for the actions of Malaysian and non-Malaysian perpetrators.

Discussion

The demographic data analysis shows that the participants constituted a represented sample for the study to examine the role of social identity on empathy for victims and moral justification of perpetrators’ actions. According to Coolican (2019), a representation of the target population is a critical requirement in collecting data because it determines the external validity of the information. The use of Malaysians as participants was crucial because it offers a unified social identity and eliminates confounding factors. Moreover, a balanced number of male and female respondents ensured gender representation in the study. Collecting information from adults between 19 and 72 years assured representation and collection of valid and reliable data since some had the experience of having maid in their households.

The independent sample test demonstrated that empathy for the victim was statistically significantly higher in the case of the Malaysian perpetrator than when the perpetrator was non-Malaysian. The differences in the levels of empathy are in line with the social identity theory, which stipulates that people have a favourable view of members in an ingroup when compared to those in an ingroup (Hogg, 2016; Adelman & Dasgupta, 2019). Fourie et al. (2017) argue that race, ethnicities, culture, and group identity explain the existence of empathy bias between varied groups. In this case, the Malaysian case of the perpetrator informed the respondents that the victim is an ingroup member who requires favourable treatment. Krautheim et al. (2019) observe that group membership is a strong modifier of neural resonance and causes empathy bias. Therefore, variation in the degree of empathy is in tandem with the social identity theory in the aspect of the intergroup relationship.

Regarding the moral justification, the independent sample t-test established that the differences in the means are not statistically significant between Malaysian and non-Malaysian perpetrators. These findings suggest that Malaysians had an equal perception of perpetrators’ actions as immoral treatment of maids. In contrast, Moncrieff and Lienard (2018) established that people judge harmful actions of out-group members more punitively than those of ingroup members. Further findings show that immoral behaviours in ingroup tend to degrade reputation and attract utilitarian punishment (Fousiani et al., 2019). However, in this case, Malaysians did not have a significant moral justification for the immoral actions of the perpetrator.

Conclusion

Social identity is a factor that influences the way individuals perceive issues in society. In this case, the study sought to determine if empathy for victims and the moral justification of perpetrators’ actions vary according to social identity. According to Malaysians’ data, the level of empathy is higher when victims are Malaysians than when they are non-Malaysians. However, the level of moral justification did not differ significantly between Malaysian and non-Malaysian perpetrators. Therefore, the study holds that participants had biased empathy for victims according to social identity theory, but they had a similar level of moral justification.

References

Adelman, L., & Dasgupta, N. (2019). Effect of threat and social identity on reactions to ingroup criticism: Defensiveness, openness, and a remedy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(5), 1-14.

Batson, C. D., Chang, J., Orr, R., & Rowland, J. (2002). Empathy, attitudes, and action: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group motivate one to help the group? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(12), 1656–1666.

Batson, C. D., Polycarpou, M. P., Harmon-Jones, E., Imhoff, H. J., Mitchener, E. C., Bednar, L. L., Klein, R. T., and Highberger, L. (1997). Empathy and attitudes: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group improve feelings toward the group? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(1), 105–118. Web.

Bocian, K., & Wojciszke, B. (2014). Self-interest bias in moral judgments of others’ actions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(7), 898–909. Web.

Coolican, H. (2019). Research methods and statistics in psychology (7th ed.).

Fourie, M., Subramoney, S., & Gobodo‐Madikizela, P. (2017). A less attractive feature of empathy: Intergroup empathy bias. Intech Open, 1(1), 46–62. Web.

Fousiani, K., Yzerbyt, V., Kteily, N., & Demoulin, S. (2019). Justice reactions to deviant ingroup members: Ingroup identity threat motivates utilitarian punishments. British Journal of Social Psychology, 58(4), 869-893.

Hogg, M. A. (2016). Social identity theory. Understanding peace and conflict through social identity theory, 3–17.

Huang, S., & Yeoh, B. S. A. (2007). Emotional labour and transnational domestic work: The moving geographies of “maid abuse” in Singapore. Mobilities, 2(2), 195–217. Web.

Krautheim, J. T., Dannlowski, U., Steines, M., Neziroğlu, G., Acosta, H., Sommer, J., Straube, B,, Kircher, T. (2019). Intergroup empathy: Enhanced neural resonance for ingroup facial emotion in a shared neural production-perception network. Neuroimage. 194(1), 182–190.

Lee, Y.-T., & Ottati, V. (2002). Attitudes toward U.S. immigration policy: The roles of in-group-out-group bias, economic concern, and obedience to the law. The Journal of Social Psychology, 142(5), 617–634. Web.

McGraw, K. M. (1998). Manipulating public opinion with moral justification. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 560(1), 129–142.

Mokhtar, M. (2018). Datin gets jail, but what about Suyanti? Free Malaysia Today.

Moncrieff, M., A., & Lienard, P. (2018). Moral judgments of ingroup and out-group harm in post-conflict urban and rural Croatian communities. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(212), 1–18. Web.

Reicher, S. D. (1982). The determination of collective behaviour. Social identity and intergroup relations, 41-83.

Servaes, J. (2000). Reflections on the differences in Asian and European values and communication modes. Asian Journal of Communication, 10(2), 53–70. Web.

Tan, P. H. (2011). The economic impacts of migrant maids in Malaysia (Doctoral dissertation). Web.

Tarrant, M., Branscombe, N. R., Warner, R. H., & Weston, D. (2012). Social identity and perceptions of torture: It’s moral when we do it. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(2), 513–518.

The Star. (2019). Look into abused maid’s case, A-G told.

The Straits Times (2018). Indonesia mulls ban on sending maids to Malaysia after abuse case. Web.