Introduction

Vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) are viral or bacterial infections that are controlled through the use of vaccines. About tens of thousands of Americans contract VPDs, leading to high hospitalizations and mortality rates (Charania et al., 2019, p. 2661). Vaccines are the most effective protection against VPDs and have been instrumental in reducing the number of cases.

Despite being affordable and effective, measures by public health organizations have shown significant effects in eradicating vaccine-preventable diseases. In the last four decades, the vaccines have effectively eradicated smallpox and other illnesses, including measles, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and poliomyelitis (Charania et al., 2019, p. 2667). The report will discuss symptoms of diphtheria, measles, and tetanus, as well as the treatments of these diseases and vaccines against them.

Diphtheria

Diphtheria occurs as a result of toxins released by Corynebacterium diphtheriae. The disease is spread from one person to the other. The disease affects many body regions, including tonsils, throat, nasal mucosa, inner ear, vagina, and skin. The main signs of diphtheria include a grey coating on the tonsils and throat, irritation of the throat, inflamed glands, breathing problems, discharge from the nostrils, fever, chills, and fatigue. The symptoms appear anywhere from two to five days after infection. Diphtheria might be asymptomatic in some people, while it might be less symptomatic in others; these people are nonetheless considered carriers of the illness (Truelove et al., 2020, p. 95).

There are two forms of diphtheria, which are respiratory and skin infections. Respiratory ditherer manifests itself through a sore throat and slight fever. In severe cases, respiratory diphtheria can cause death due to airway obstruction resulting from enlargement of the pharynx and trachea. Respiratory diphtheria can also cause myocarditis and neuritis. Conversely, cutaneous diphtheria manifests itself as skin sores and is considered less dangerous than the respiratory variant and accounts for fewer deaths overall.

Diphtheria is a severe disease that requires prompt and aggressive treatment. Diphtheria treatment includes two strategies: the use of antibiotics or antitoxins. Antibiotics such as penicillin eliminate bacterial infection from the body and reduce contagiousness. The second option involves using antitoxin, which neutralizes diphtheria toxin in the body. The antitoxin is mainly administered to patients suspected to have diphtheria.

The antitoxin is injected into the vein or muscle, but skin allergy tests must be conducted to ensure the person is not allergic to the medication (Truelove et al., 2020, p. 96). Diphtheria patients, including children and adults, require hospitalization for treatment. They might be isolated in an intensive care unit to prevent the disease from spreading to unvaccinated individuals.

Diphtheria is prevented through the use of toxoid vaccines that prevent symptoms by stimulating the body’s natural response to the toxin by producing antitoxin antibodies. The primary vaccinations are administered at 6, 10, and 14 weeks of age. Adults receive a booster injection every ten years, while children and adolescents receive one every four to seven years(Muratova and Qarshiyeva, 2022, p. 118). Some of these vaccines also include vaccinations for cellular pertussis and tetanus. DTaP, Tdap, DT, and Td are all available vaccinations. Adults receive the Tdap vaccine, while children receive the DTaP vaccine. The DTaP vaccination, given multiple times to children, is the most popular type (Muratova and Qarshiyeva, 2022, p. 118).

Children who react adversely to the pertussis vaccine are given DT, which does not contain the viral agent. Adults and teenagers should have a tetanus booster shot every ten years (Muratova and Qarshiyeva, 2022, p. 119). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2022) advised using Tdap booster to protect against pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria. Pain or discomfort at the injection site, moderate fever, and similar reactions are common but short-lived side effects of immunizations. Some patients, however, may encounter more severe manifestations. For example, if the tetanus or pertussis vaccine causes an allergic reaction, the patient should notify their healthcare provider immediately.

Mumps

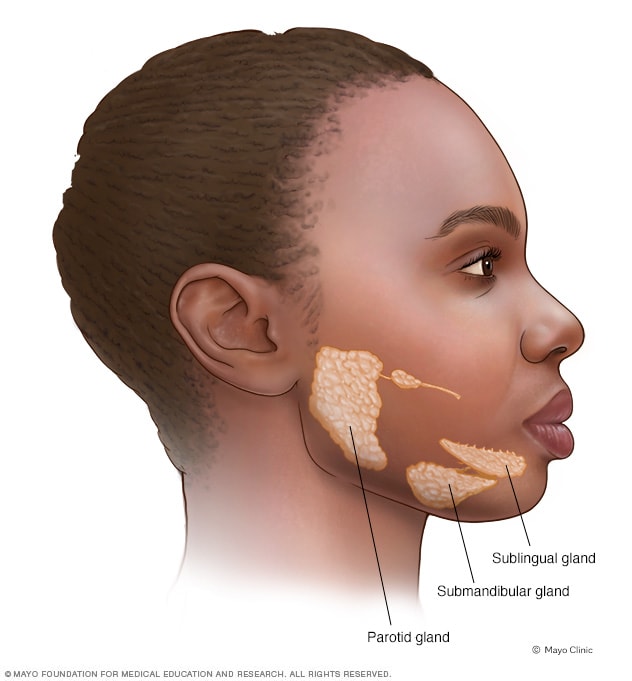

Mumps is a contagious disease caused by a virus. The disease can be transmitted through close contact between infected people and the exchange of saliva and nasal secretions. The disease severely affects the parotid glands. The most noticeable symptom of mumps is the enlargement of the salivary glands. The disease outbreaks in the United States are uncommon due to widespread immunization. Mumps mainly affects the unvaccinated, while the vaccinated suffer fewer and milder symptoms if they contract the disease.

The disease’s symptoms often appear two weeks after exposure to the pathogen. Initial flu-like symptoms may include fatigue, body pains, headaches, nausea, and a low-grade temperature. Over the following several days, a high temperature of 103°F (39°C) and enlargement of the salivary glands appear (Lau & Turner, 2019, p. 390). There is a chance that the glands’ swelling will not happen all at once; instead, it can happen intermittently and hurt. Figure 1 below shows the inflamed swelling glands of a mumps-infected person (Charania et al., 2019, 2664). From the moment of virus contact until the parotid glands enlarge, there is a period of contagiousness. Even though most people develop symptoms of mumps after infection, some have none or only minor symptoms.

No particular antiviral drug exists to treat mumps since the sickness usually goes away independently. The main goal of treatment is to reduce symptoms, such as the discomfort caused by parotitis orchitis, through painkillers (Charania et al., 2019, 2664). Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is not used to treat measles specifically, although it has been used to treat some autoimmune-based measles symptoms successfully. Another possible remedy is interferon alfa-2b administered subcutaneously to treat mumps orchitis (Pinkbook et al., 2019). Using interferon alfa-2b therapy can help people with mumps orchitis feel better and avoid testicular shrinkage.

The measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine is one of the most effective vaccines against mumps. Since its licensing in 1967, the MMR vaccine has seen widespread use across the globe in 114 countries (Mun et al., 2023, p. 6). The first dose is administered between 12 and 15 months, and the second varies by country (Mun et al., 2023, p. 6). Herd immunity against the mumps virus is thought to be achieved after 90% of the population is vaccinated (Su, Chang, and Chen, 2020, p. 1689).

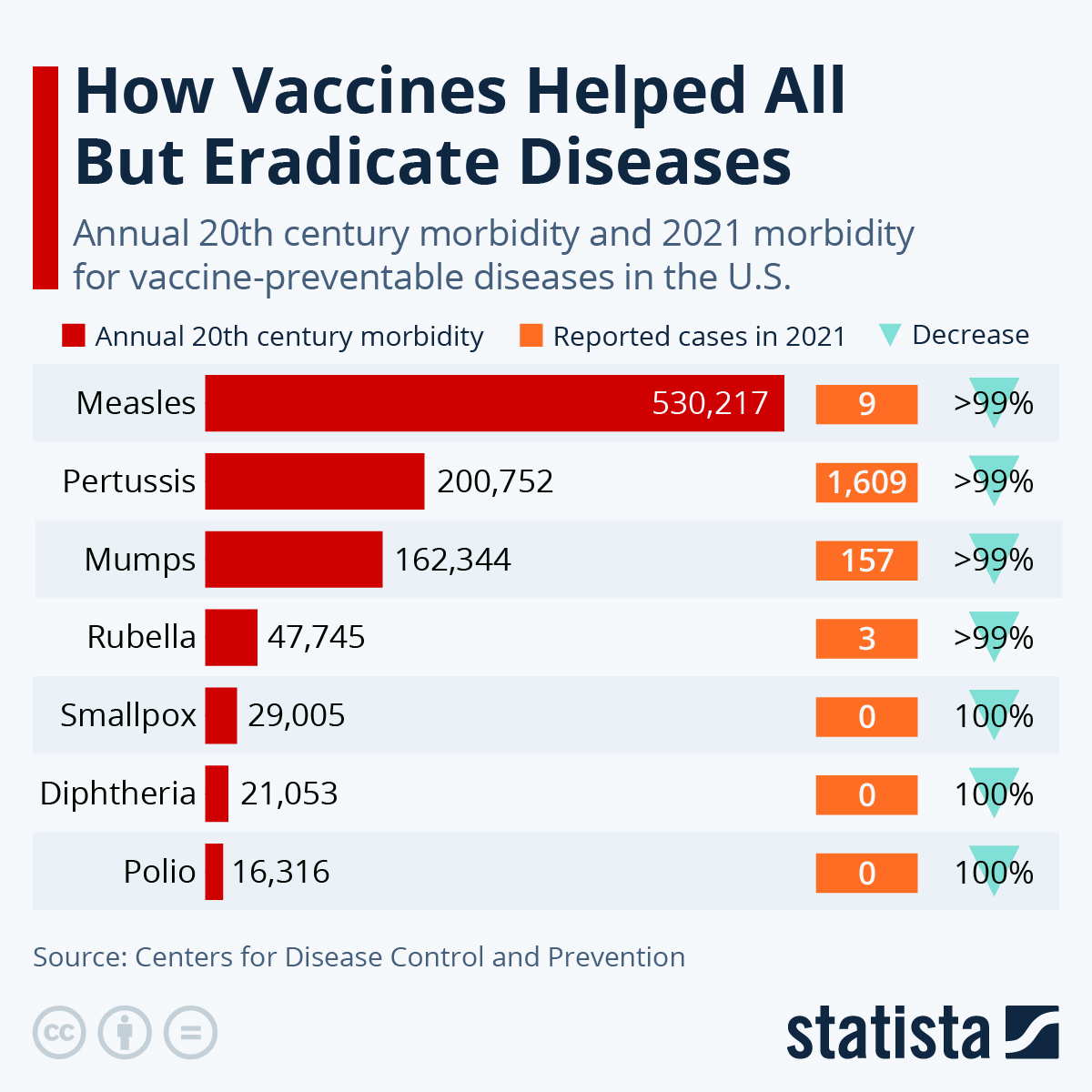

Inadequate vaccination coverage in young children can cause an epidemiological shift in the age distribution of mumps, as was seen with rubella before widespread immunization (Mun et al., 2023, p. 6). This could lead to more severe illness and complications than before widespread immunization. Since the licensing of the measles vaccine in 1968, countries that have implemented measles vaccination have witnessed a substantial decline in measles incidence (Di Pietrantonj et al., 2022, p. 26).

For instance, the number of mumps incidences in the US decreased by 99 percent between 1968 and today (Di Pietrantonjet al., 2022, p.26). Finland implemented a two-dose MMR vaccination regimen in 1982, and 16 years later, indigenous mumps were eradicated, with only rare imported cases remaining (Di Pietrantonj, 2022, p. 26). The same study has reported that reductions ranging from 97% to over 99% have been observed in other European countries using a two-dose schedule (Di Pietrantonj, 2022, p. 27). In nations employing a single-dose regimen, reductions ranged from 88% to 95% (Di Pietrantonj,2022, 27). Despite the effectiveness of mumps vaccination, there are still occasional outbreaks. Graph 1 demonstrates the trends in how the prevalence of mumps and other vaccine-preventable diseases has fallen.

Tetanus

Clostridium tetani bacteria cause tetanus infections by secreting a toxin that causes painful muscle contractions. This medical condition is also known as “lockjaw” because it may result in the neck and jaw muscles contracting, making it challenging to chew or open the mouth. Tetanus symptoms typically appear 7-10 days after the initial infection, though this time frame can range from 4 days to 3 weeks or even months (Weant et al., 2021, p. 18). When an injury is not as close to the brain, it usually takes longer to show symptoms. More severe symptoms are seen in patients with shorter incubation periods.

Since tetanus is incurable, patients need immediate medical attention and ongoing support as the disease progresses. Tetanus treatment plans include wound care, symptom-relieving medication, and supportive care. The onset of symptoms occurs after two weeks, and full recovery could take another month. As part of wound care, the wound must be cleaned to extract materials that could serve as a breeding ground for bacteria. The healthcare staff will also remove any necrotic tissue that could provide nutrients to bacteria.

Medications are also used in the fight against the disease. Toxins that have not yet attacked nervous tissue are the focus of antitoxin treatment. Regular tetanus immunizations support the immune system’s defense against toxins, and sedatives that calm nervous system activity can assist in managing muscle spasms. Morphine can induce sleep, and other drugs can control involuntary muscle activity like heart rate and breathing.

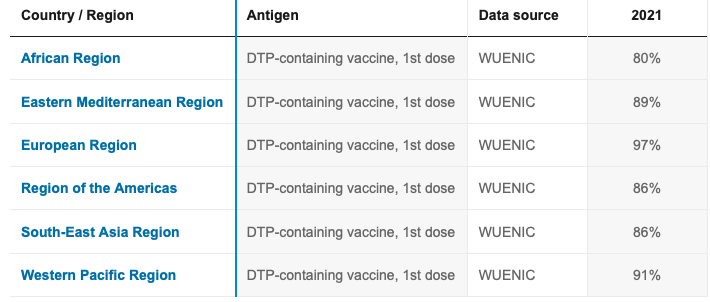

The DTP vaccine (Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis) is a combination of the three vaccines. Babies should receive the vaccine at 2, 4, 6, and 18 months old and a second time at 4 to 6 years old, with a booster shot every ten years (Pfausler et al., 2021, p. 435). Between 27 and 36 weeks of pregnancy, the vaccine should be given to expectant mothers (Pfausler et al., 2021, p. 435). Tetanus was identified as one of the most important diseases to protect against when the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) was formed in 1974 to make crucial vaccines accessible (Weant et al., 2021, p. 19). DTP3 coverage determines the percentage of toddlers given three doses of the combination vaccine in a calendar year; the DTP coverage as of 2022 is shown in Table 1.

Conclusion

The best defense against VPDs is vaccination, which has greatly contributed to the decline in incidences. Vaccines have effectively eradicated the major preventable diseases in the last four decades. Mumps, diphtheria, and tetanus outbreaks still occur, but the severity is less in vaccinated individuals. These diseases severely affect unvaccinated individuals, making it necessary for governments to make more campaigns for vaccination against VPDs to achieve a target of zero occurrence rates.

References List

Charania, N.A., Gaze, N., Kung, J.Y. and Brooks, S. (2019)‘Vaccine-preventable diseases and immunization coverage among migrants and non-migrants worldwide: a scoping review of published literature, 2006 to 2016’, Vaccine, 37(20), pp.2661-2669.

Di Pietrantonj, C., Rivetti, A., Marchione, P., Debalini, M.G. and Demicheli, V. (2020) ‘Vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in children’, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4). Web.

Mun, J., Kim, S.H., Park, J.W., Park, J.S., Park, S.J., Lee, S.H., Seo, J.J. and Chung, Y.S. (2023) ‘Viral detection from negative mumps cases with respiratory symptoms in Gwangju, South Korea, in 2021’, Journal of Medical Virology. Web.

Muratova, G.S. and Qarshiyeva, D.R. (2022) ‘Basic Symptoms of Infectious Diseases’, European Journal of Life Safety and Stability (2660-9630), 13, pp.117-121.

Pfausler, B., Rass, V., Helbok, R. and Beer, R. (2021) ‘Toxin-associated infectious diseases: tetanus, botulism and diphtheria’, Current Opinion in Neurology, 34(3), pp.432-438. Web.

Ritcher, F. (2022) How vaccines helped all but eradicate diseases. Statista. Web.

Su, S.B., Chang, H.L. and Chen, K.T. (2020) ‘Current status of mumps virus infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and vaccine’, International Journal of environmental research and public health, 17(5), p.1686. Web.

Truelove, S.A., Keegan, L.T., Moss, W.J., Chaisson, L.H., Macher, E., Azman, A.S. and Lessler, J. (2020) ‘Clinical and epidemiological aspects of diphtheria: a systematic review and pooled analysis’, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 71(1), pp.89-97. Web.

Weant, K.A., Fields, B., Guerin, C.S. and Justice, S.B. (2021) ‘Do not be stiff: a review article on the management of tetanus’,Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal, 43(1), pp.10-20. Web.

WHO (2023) Diphtheria tetanus toxoid and pertussis vaccination coverage. Web.