Introduction

In the comparative forensic academic environment, the Thai system occupies a marginal position. Based on civil law rather than common law, it is characterized as a deviation from more advanced forms of justice. Various institutions have reported that human rights violations are common in Thailand as part of the implementation of legislative prescriptions or control over public political participation.

For instance, the US Department of State (2020) reports that in 2018 and 2019, the Thai government and its agents committed unlawful or arbitrary killings. At least 16 suspects were killed by state agents during the arrest process in 2019 alone (US Department of State, 2020). This problem is quite old in a country that regularly signs and updates human rights declarations; however, it does not comply with the instructions.

There is systematic persecution of activists who expose large companies that violate workers’ rights to regular employment. Moreover, there is no definition of torture in the Thai legal system. Yet, torture is routinely used against journalists, opposition leaders, political activists, and prisoners, referring to the actions as ‘attitude adjustment’ meant to force the government (Nayak, 2021). Although Thailand has been a member of the United Nations Convention against Torture for several years, stories of police killings and other abuses of power within the legal system and its enforcement regularly surface (Nayak, 2021). However, in the context of recent research, this system deserves attention and consideration as it has a more victim-centric attitude than many others.

Structure of the Thai Criminal Justice System

The Court of Thailand consists of three instances, each connected to the trial in succession in the event of repeated appeals. Technically, all open cases must be processed through the Court of First Instance, which encompasses general, juvenile, and family courts (McCargo, 2020). An appeal against either a judgment or the procedure of the law itself is sent to the Court of Appeal, and only in cases that need outside intervention is the case remitted to the Supreme Court for reassignment by the Chief Justice.

In the Thai justice system, victims of crime can hire prosecutors and conduct independent criminal investigations and prosecutions on their own, if necessary, including other victims of the crime in the prosecution. The victim of a crime has more flexibility than those in the West, but it becomes more challenging for the defendant to choose such a lawsuit (McCargo, 2020). Due to the possibility of organizing an independent accusatory process, the defense lawyer must answer several opponents simultaneously.

Terrorism and Transnational Crime Policies

Thailand’s transnational anti-crime policy is primarily focused on addressing the issue of organized crime within the Kingdom. Thailand signed the United Nations Convention on Combating International Crime in 2013 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kingdom of Thailand, 2022). The Kingdom was again drawing attention to victims’ rights and privacy, especially in cases related to human trafficking.

Application of Concept of Comparative Criminal Justice

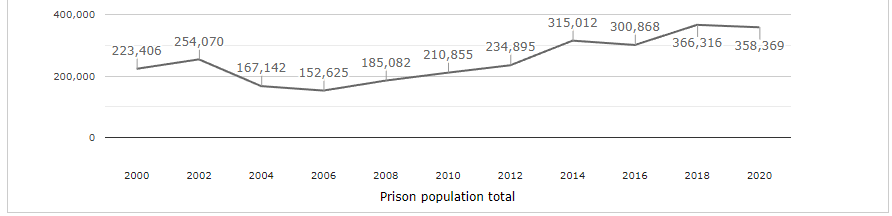

With all the above flexibility of the criminal system and its focus on meeting the requirements of the injured party, it should be noted that its effectiveness burdens the state, revealing the problems of the behavioral code of the population. The number of prisoners for crimes under the penal code in Thailand is high to such an extent that the prisons are overcrowded, with the country having the 10th-highest imprisonment rate per population in the world (Jacobson et al., 2017). The maintenance of prisoners turns out to be inaccessible to the state, which is why the consulate proposes several amendments to the criminal code.

According to these changes, some crimes will receive administrative status rather than criminal. Based on this, a different punishment will be imposed on the defendant, particularly a fine (Samuiforsale.com, 2022). The system is facilitated by abolishing prison sentences for certain law violations, such as writing bad checks or violating copyrights. Capital crimes such as murder, robbery, or violence against a person should still be punished by imprisonment. This case demonstrates that the Thai legal system is a particular example of freedom of criminal prosecution within the context of a high crime situation per capita.

As signs that the Thai legal system is deficient, consider the rebellious and thought-provoking behavior of Khanakorn Pianchana. This judge from Thailand was supposed to deliver a court verdict that, according to the principles of the Thai Criminal Code, promised the accused the death penalty as the highest degree of punishment. Moreover, he claimed that the ruling was being rewritten precisely by manipulating the case over which he presided (ICJ, 2020). As a result, after reading a manifesto against the Thai penal system and its interference in some of the fundamental rulings, this judge committed suicide, according to his statements, to not issue death sentences and thus protect himself from lousy karma.

This case highlights the unreliability of certain fundamental elements of the legal system in Thailand, underscoring the potential for state intervention in the judiciary, as well as the ambiguity and arbitrariness in the interpretation and application of the law (Fullerton, 2019). Combined with relatively large judicial arbitrariness and a high number of prisoners, it still makes sense to argue that the Thai criminal justice system falls at the margins of legal systems, at least from a Western perspective.

Thai vs. American Criminal Justice Systems

The specific elements of the Thai legal system differ significantly from the general law system of criminal procedure in the West. The inability of suspects to obtain a jury trial under the Thai legal system differs significantly from the Western justice system (McCargo, 2020). This difference can be fatal in various situations, as it can lead to an unfair attitude towards the judicial process and, consequently, an overly strict or completely unfair sentence. In Western practice, this right is fundamental and helps avoid a judge’s predetermined and unfair approach to a person under investigation(McCargo, 2020). Prosecutors thus have an excessive opportunity to influence the judge’s decision, which is final and non-negotiable.

Furthermore, in the Thai legal system, a plea bargain is not possible, unlike in the West, where it allows the accused to relieve themselves of part of the legal responsibility in the event of recognizing the crime committed. After hearing the evidence of the accusation in the Thai criminal court, the judges decide what constitutes a crime (Thailand Law Online, 2022). On the other hand, the prosecutor turns out to be a collector of evidence in favor of the prosecution even before the prosecution itself is brought, being an employee of the prosecution in a more direct form than in the Western legal system.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the growing population of prisoners in Thailand speaks to the growing efficiency of the judicial system but may also point to the principles of victim-generating justice. The Thai criminal prosecution system differs from the Western one in several ways and is pushed out by many to the margins of the current discourse on the law (McCargo, 2020). Despite this, the victim-centeredness of Thai justice and the principle of independent investigation and prosecution demonstrate that the freedom of the Thai judiciary from precedent sheds new light on the principles of judicial procedure.

References

Fullerton, J. (2019). Thai judge shoots himself in court in an apparent suicide bid. The Guardian.

International Commission of Jurists, ICJ. (2020). Thailand: ICJ mourns the passing of Judge Khanakorn Pianchana.

Jacobson, J., Heard, C., & Fair, H. (2017). Prison: Evidence of its use and over-use from around the world. ICPR.

McCargo, D. (2020). Fighting for Virtue: Justice and politics in Thailand. Cornell University Press.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kingdom of Thailand. (2022). Thailand ratifies UN Convention against transnational organized crime (UNTOC) and protocol to prevent, suppress, and punish trafficking in persons, especially women and children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against transnational organized crime.

Nayak, S. (2021). Culture of torture and intimidation: The military in Thailand. The Yale Review of International Studies.

Samuiforsale.com. (2020). Thailand Penal Code Thai Criminal law.

Thailand Law Online. (2022). Criminal Law in Thailand.

US Department of State. (2020). 2020 country reports on human rights practices: Thailand.