Introduction

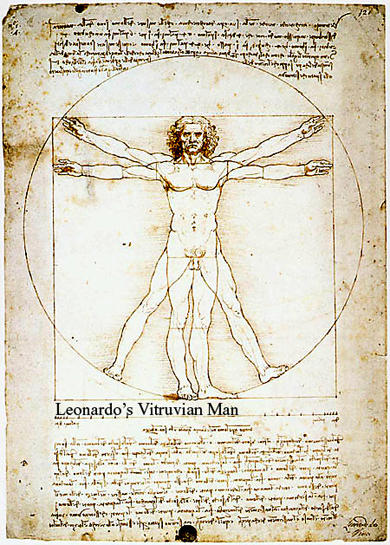

In Vitruvian Man, Leonardo Da Vinci presents a carefully studied illustration of human anatomy. Leonardo studied human anatomy as an artist as well as a scientist and philosopher. His treatment of art was not restricted to aesthetics and beauty, but it represented medium to search for a higher truth. A man, belonging to renaissance of 14th to 17th century, that fused the difference between an artist, philosopher, and scientist completely, brought this unique drawing to life that present science and art simultaneously. The close connection between art and science, which can be found through, the close study of geometry and architecture is evident in Leonardo’s work. His paintings and drawings reverberate with the classical belief of a divine connection between man, nature, and universe, which he tries to establish through his work. Thus, the essay tries to answer the question, what is the significance of, and importance of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. This essay is divided into two sections: first will study the drawing of Vitruvian Man and the idea that he presented in his famous painting, Christ as the Savior of World (Salvator Mundi). The essay discusses the drawing and Salvator Mundi by Leonardo Da Vinci that is informed by the same ideas. The drawing and the painting are compared to understand the relevance of the theme to Leonardo Da Vinci.

Vitruvian Man

The Vitruvian Man, complete in 1490 by Da Vinci did not aim at creating a perfectly proportioned male figure, instead aimed at created a proportioned replica of an average man by overlapping a circle and a square (Vasari, 1991). In a way, he tried to demonstrate through this drawing that using the ratio of a square and a circle, which the renaissance philosophers called the divine ratio, one attain correct proportions of a human figure. Correct geometric proportions bore the secret to creating a proportionate human figure. Though this dabbling with geometry and human form was not new to the Renaissance and in antiquity as artists and scientists then believed that the human proportions were based on the architectural proportion, where the body was an architecture that was built on perfect proportions. Therefore, the idea was to derive the ideal proportion through the drawing of an idea man. In other words, the aim of drawing a human figure inside a square and a circle means trying to gauge the ideal proportion that can provide equilibrium to other architectural figures. That is why the classical architectural belief reflects usage of geometric proportions of an ideal man.

Reference to the classical book of architecture by Vitruvius Polio shows that the perfect human proportions are derived from the chapters in book, De Architectura (About Architecture) dealing with sacred architecture (Vasari, 1991). The work by Vitruvius shows that the ratio formed by placing the circle with the square provided the golden ratio that was used in building temples during antiquity. Art critique Elizabeth Podles argues that in Leonardo’s Vitruvius Man, the square represents the stand that holds the entire object. At the same time, the circle is the fulcrum on which the whole body revolves:

The square, with its solid base and equilateral sides, stands firm and will not be moved. It represents stasis. The circle, on the other hand, is created by the perpetual motion of a single point around a still central; that is, it stands by analogy for endless action. (Podles, 2012, p. 62)

Similar proportions are evident in Da Vinci’s Vitruvius Man. Thus, Da Vinci conceded with the idea that the divine proportion with which man has been created can provide perfect balance and symmetry to any architectural form. This idea is embedded in the study of the proportions that Da Vinci pursued through most of his artwork (Richter, 1970). That is why he created a drawing of a body with outstretched arms and legs, which he believed, created a perfect square and a body with the spread eagle position created a circle (Richter, 1970). The outstretched legs create an equilateral triangle. According to geometric philosophy, the centre of a square and circle are not the same. Thus, the centre of gravity of the Vitruvius Man lies below the naval (Richter, 1970). Leonardo, therefore, created a picture that showed the connection between the universe and man. Vitruvian Man, drawn with perfect proportion drawn from Nature, becomes a symbol of unification between man and universe. This symmetry becomes the central idea of the drawing of Vitruvian Man.

Comparison of Vitruvian Man to Salvator Mundi

The divine proportions that are so specifically studied in the complete human figure in Vitruvian Man are imposed on the painting of the portrait of Jesus Christ in Vinci’s painting called Salvator Mundi. This painting was recently discovered in 2011.

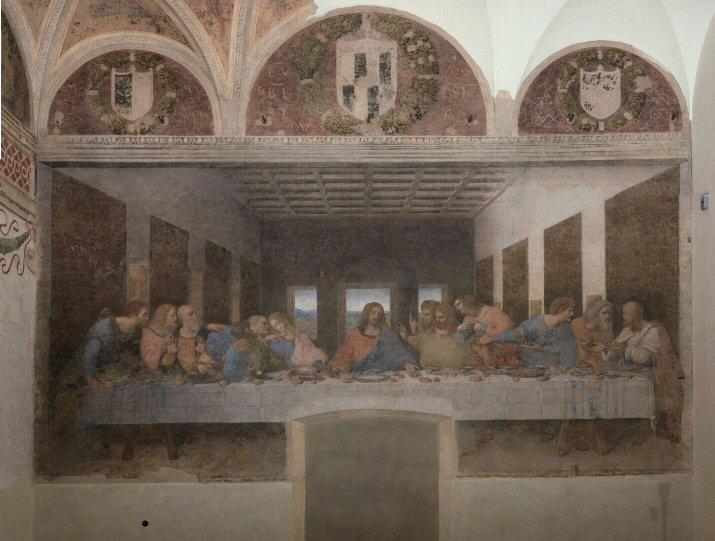

Figure 2 shows the painting and depicts the presence of the divine ratio in work. Leonardo’s obsession with the divine ratio became evident when he drew the illustrations for Luca Pacioli’s book The Divine Proportion (Pedretti, 1973). The presence of this ratio has been observed in other works that he has created, such as The Annunciation painted in 1473 (figure 3) and The Last Supper drawn in 1495 (figure 4).

The presence of the implementation of the golden ratio is apparent in Leonardo’s painting, Salvator Mundi. The portrait shows that the absence of any lines in the background to this portrait, unlike that of Mona Lisa, creates a landscape-less depiction (Atalay, 2006). However, the presence of the ratio is apparent in the dimension of the hand that holds the orb and the right hand that point upward. The orb represents a perfect circle. The golden proportions are also found in the painting of the emblem embroidered on Christ’s robe. The authenticity of the recently discovered painting of Leonardo is based on the belief of the painter that “painting is a science” and “it relies on a systematic body of knowledge based on deep scrutiny of cause and effect in nature” (Kemp, 2011, p. 174). Following the philosophy that dominates most of Leonardo’s work, it can be intuitively said that he believed that there is a hidden connection between nature and man, and work of art or science are simple the imitators of the hidden treasures (in this case the divine proportion) of nature. Therefore, the stress of Leonardo’s work has always been to create a drawing, sculptor, or tool that followed the basic principle of emulating the divine ratio i.e. a circle embedded in a square (Ndirika, Lee, Holden, & Green, 2010). Thus, the presence of the manifests of nature through the depiction of the light and shade is present in the picture of Salvator Mundi.

The interplay of the divine and the mortal are closely done in the painting. Leonardo gives Christ the features of a man, with the divine proportion that he believed was possessed by all man. While simply looking at the painting, one gets the impression of a man, realistically drawn, with accurate proportions. However, the presence of the orb (and not a globe) in the left hand is bewildering. Why does not Leonardo draw a globe? Why does he draw a crystal-like ball in Christ’s hand with dots of light in it? The reason may be found in the classical Ptolemaic belief that the stars and the cosmos were embedded in a crystal ball, and Jesus is the saviour of humankind, could also be visualized as the saviour of the cosmos (Kemp, 2011). Thus, Jesus, the Son of God, is shown outside the sphere of cosmos, for he who created the world and him who moves the sphere to let life continue.

The divine proportions represented in the painting and the drawing of Leonardo show the painter’s belief in the cosmic interconnection of man and nature. Nature, according to the philosophy of Leonardo, created by God, holds the secret to the balance and equilibrium of the world, crafted through the golden ratio (Keele, 1983). Both the Vitruvian Man and Salvator Mundi present the predominance of nature over body and form (Kemp, 2006). The perfect ratio that the Vitruvian Man demonstrates through explicit drawings of circle embedded in the square shows is implicitly used by Leonardo in most of his other paintings, and most importantly in Salvator Mundi. The drawing and the painting by Leonardo represent the idea of the cosmic presence in man.

References

Atalay, B. (2006). Math and the Mona Lisa: The Art and Science of Leonardo da Vinci. London: Smithsonian Books.

Keele, K. D. (1983). Leonardo da Vinci’s Elements of the Science of Man. New York,: Academic Press.

Kemp, M. (2006). Leonardo da Vinci: the marvellous works of nature and man. London: Oxford University Press.

Kemp, M. (2011). Sight and salvation. Nature , 479, 174-175.

Ndirika, S., Lee, J., Holden, S., & Green, J. S. (2010, December). Squaring the Circle: Proving the da Vinci Code. AUANews , pp. 24-25.

Pedretti, C. (1973). Leonardo: A study in chronology and style. Los Angeles: Univ of California Press.

Podles, M. E. (2012, May/June). Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. Touchstone , pp. 62-63.

Richter, J. P. (1970). The notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. London: Courier Dover Publications.

Vasari, G. (1991). The lives of the artists. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.