Introduction

Ancient people have not left a wide range of resources about their lifestyle. Modern people know a measurable number of written memorials, so archeological artifacts appear to be the most informative method of acquiring knowledge about ancient cultures. They involve architecture and sculpture, which specifics can be helpful in fulfilling this intention. However, some resources cause multiple questions, which are difficult to resolve, and the Warrior with Trophy head is one of them.

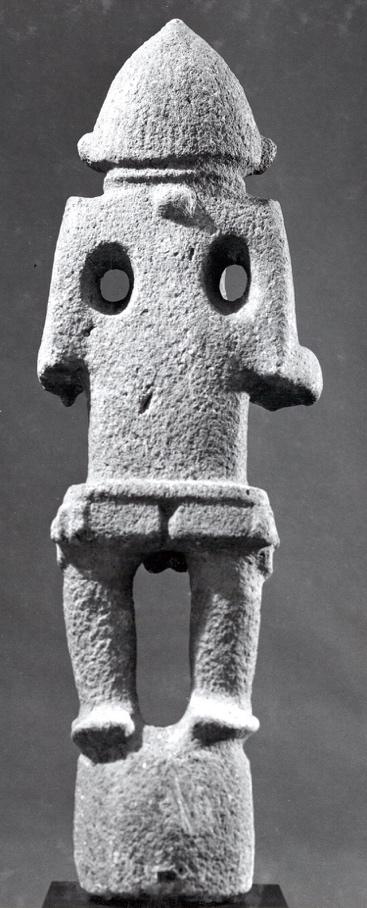

Figure 1 depicts a warrior with a trophy head and an ax. The shapes, details, and abstract positions, such as the holes in the shoulders, offer a vast amount of potential research to interpret their meaning correctly. It may regard the visual issues or the position of a person in society. Using both information sources and historical evaluation, this research aims to provide an in-depth look into the meaning and cultural value of the sculpture, with a focus placed on the minute details of the composition and the symbolic nature of the components of the work. In essence, the exploration of the selected piece of Mesoamerican sculpture will revolve around the theory of the prevalence of militarism in the region and visual purposes.

Literature Review

There are numerous works devoted to the exploration of South and Central American culture. For instance, a group of researchers, Pillsbury, Joanne, Timothy F. Potts, and Kim N. Richter, supply comprehensive and the most relevant information on the exhibition, where this figure is presented. Another scientist, Karl Andreas Taude, provides deep insight into the everyday routine of the local population through the perspective of iconography. His research appears to be informative for writing this paper in the context of history, as it covers a significant number of details regarding the life of the population. This aspect includes information of the prominent position of warriors in this society, respectful attitude to them from other groups of the population, and their high status.

Consequently, the trophies in the warrior’s hands are symbolistic, and Amy Scott’s article involves exploring pottery development in the aforementioned region. The author supplies essential knowledge of the methods of producing different types of sculptures and explains the meaning of images on them. An illustrative example is the warrior’s pendant, which was characteristic for people of high status.

Continuing the topic of war trophies, Francisco Javier Carod-Artal. And John Hoops highlights the importance of depicting enemies’ head in such figures. They used to draw attention to the characters’ acts of bravery and fighting skills. In addition, the exploration of museum collections conducted by Warwick Bray contributed to describing the specifics of the relationships between people in that historical period. As conflicts and fights for freedom and lands were a common sight, people used to respect warriors, as their role in resolving the issues mentioned above was considerable. John Verano approaches this topic too, but from the perspective of sacrifice tradition, which is common in this region.

Formal Analysis

Warrior with Trophy Head is an ancient sculpture made of stone. The author of the figure is unknown, and the approximate date of creation is 300-800 years A. D. This type of artwork is characteristic of the Costa Rica region, where the images of thorny bearers holding an ax in one of the hands were widespread. There are numerous variations on this subject, and particularly this one is referred to Chiriquí, Aguas Buenas Phase culture. It is currently presented in The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and appears to be a part of Golden Kingdoms Luxury & Legacy in the Ancient Americas exhibition.

As for the visual characteristic of this work of art, it is quite large for figures of that period, namely it is 36 inches in height, 11 and a half inches in width, and 9 5/16 inches in depth. The material for the sculpture is volcanic rock, and the color of the figure is nude. As can be seen in Figures 1 and 2, the author used straight lines, so the body shapes of the character are sharp. It is also worthy of mentioning that the sculpture seems to be flatty to some extent.

The man wears a conical helmet, and these objects point to his role in ancient society. It is highly likely for him to be a warrior, who had won a bloody battle. According to Figure 1, his face with the combination of his war trophies conveys calm and pride for his acts of bravery. In addition, on his neck, the warrior probably has the skin of four capuchin monkeys or coatimundis, which are referred to the raccoon family. This pendant appears to be symbolistic for this culture, as people of high ranks could afford such jewelry.

Contextual Analysis

The most vital details about the given piece of sculpture are its location in Costa Rica and the helmet depicting a soldier or warrior. The historical context of the region in Mesoamerica is critical in understanding the key intricacies of the sculpture and its meaning. The anthropomorphic group of sculptures includes items made in the form of people preserving their basic anatomical features but including abnormal shapes, limbs, and expressions through aspects of art such as line, depth, and color. Figurines with subtle human features can be identified as images of people. Within these, four main features of the typology of statuettes can be distinguished, such as gender, age, social status, and sacredness.

The main purpose of this assessment is to consider the geographical and chronological aspects of the distribution of early sculptural complexes in Mesoamerica and Central America. As John Verano states, clay became a widely used material initially in unsettled, complex warrior societies at the turn of the late period. All this took place in areas with a scarce resource base, especially in tropical and subtropical coastal zones, as part of the broader processes of intensification of the social component and food production. In addition, the monuments on the territory of the Pacific coast of Mesoamerica differ in scale and level from the monuments and settlements of the pre-classical era.

The lost probable version on spreading this method of sculpting implies the influence of trade routes from South America. However, after a short period of time, unique forms and variants of ornamentation of vessels appeared. In the collections of such products of the phase, researchers distinguish mainly figures of oblong shapes with perforations in the shoulders. In subsequent phases, quantitatively other forms of militarism prevail. In this phase, figurative art becomes widespread, most often represented by figures, which are periodically found on vessels as decoration. In this form, taking into account small variations, sculpture continued to exist not only within this region. It spread to neighboring territories, which once again proves the dynamic and independent development of the cultures of the Pacific coast of Mesoamerica.

In summary, the main focus of this paper is to clarify the meaning of round holes between the body and arms of the warrior. Although the current research works do not supply a comprehensive answer to this question, there are some hypotheses, which can be advanced. First of all, the author may be determined to reflect the athletic build of the character. During his historical period, people did not acquire appropriate knowledge to create the body of a human precisely, so the author highlighted the contrast between round holes and straight lines of shoulders and arms. This contrast creates the impression of a muscular man, who is courageous and strong enough to protect his tribe. This theory implies the visual effect of this ancient sculpture. Another assumption regards the tradition of this region, as such a position of the warrior’s body may mean the respect to such a high rank.

Conclusion

These days, scientists do not have a great amount of information about ancient cultures, as the only and most reliable source for exploration of this object is archeological artifacts. However, they contain numerous questions, such as the sculpture the Warrior with Trophy Head. It provides a deep insight into the everyday routine of people, who resided in Central America, and highlights the significant role of warriors in society. Nevertheless, the issue of the meaning of holes in the figure is not easy to resolve.

Images

Bibliography

Bray, Warwick. “Gold, Stone, and Ideology: Symbols of Power in the Tairona Tradition of Northern Colombia.” In Gold and Power in Ancient Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia, edited by Jeffrey Quilter and John Hoopes, 301-344. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 2003.

Carod-Artal, Francisco Javier. “Skull Cult. Trophy Heads and Tzantzas in Pre-Columbian America.” Revista de Neurologia 16, no. 55 (2012): 111-120.

Hoopes, John. “Sorcery and the Taking of Trophy Heads in Ancient Costa Rica.” In The Taking and Displaying of Human Body Parts as Trophies by Amerindians, edited by Richard Chacon and David Dye, 444-480. New York: Springer, 2007.

Hoopes, John. “Magical Substances in the Land Between the Seas: Luxury Arts in Northern South America and Central America.” In Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas, edited by Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy F. Potts, and Kim N. Richter, 54–65. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017.

Pillsbury, Joanne, Timothy F. Potts, and Kim N. Richter, eds. Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, no. 103 (2017): 195.

Schott, Amy. 2009. “A Comparison of Iconography from Northwestern Costa Rica and Central Mexico.” Minds Wisconsin Edu. Web.

Taube, Karl Andreas. Studies in Ancient Mesoamerican Art and Architecture: Selected Works by Karl Andreas Taube. San Francisco: Precolumbia Mesoweb Press, 2018.

Verano, John. “Trophy Head-Taking and Human Sacrifice in Andean South America.” In The Handbook of South American Archaeology, edited by Helaine Silverman and William Isbell, 1047-1060. New York: Springer, 2008.