Abstract

Despite reported cases of women undergoing hysterectomy without being sufficiently informed, only three states have enacted informed consent laws aimed at providing more information concerning any alternative treatments. In addition, there exists a deficiency in the study of hysterectomy, which would be required to inform changes in related policies and legislation to improve US healthcare. This study attempts to fill the gaps by exploring the perceptions and experiences of women who underwent hysterectomies in Mississippi in the absence of informed consent law. As its theoretical foundation, the work uses the health belief model to explain the behavioral aspects and beliefs. With its research questions, the paper examines the perceptions of the women, as well as the themes that emerge from their lived experiences. Because the main purpose of the study is to examine the beliefs and attitudes of women in Hinds County, the qualitative research approach guides the process of data collection and analysis.

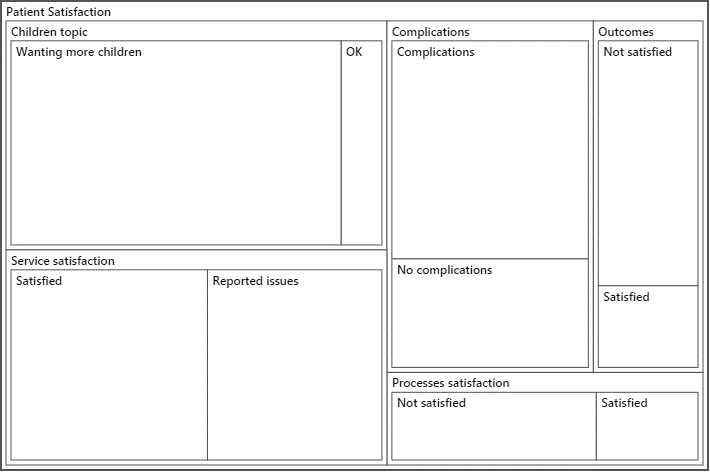

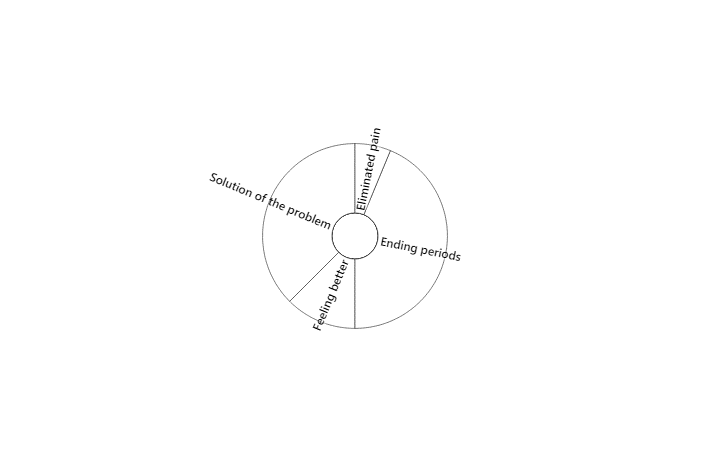

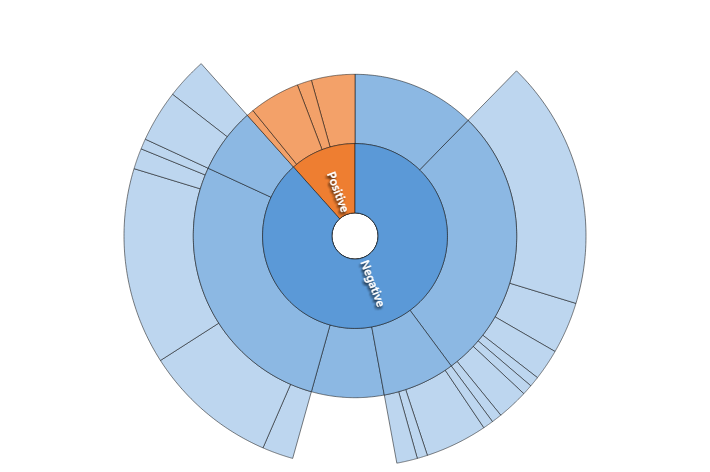

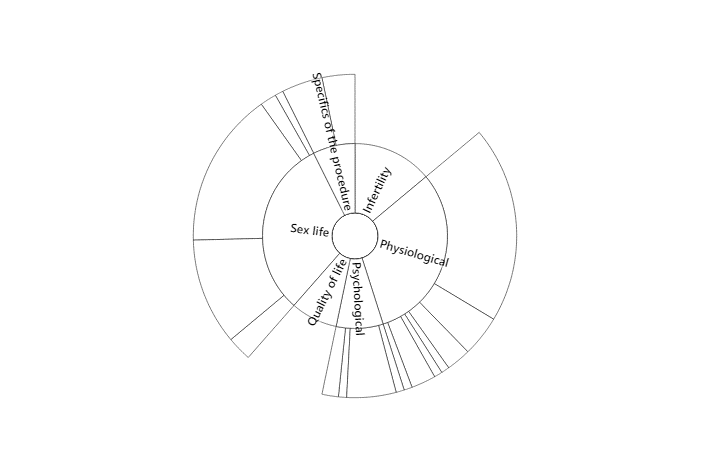

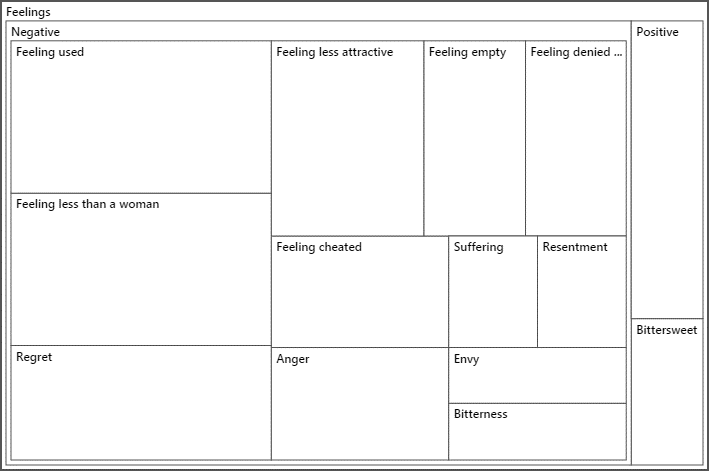

Interviews were the main data collection technique. The sample included ten women from Hinds County who underwent a hysterectomy and were between 20 and 40 years of age at the time of the research. Demographic data were also collected in order to situate the research. The analysis of the latter data involved descriptive statistics; the interview results were analyzed with the help of thematic analysis. The findings demonstrate that the women who underwent a hysterectomy in the absence of an informed consent law could be subjected to the procedure without sufficient information. As a result, the perceptions and experiences of the majority of the interviewed women were not positive. They described the negative physiological, psychological, and emotional consequences of undergoing hysterectomy without sufficient information; many of them reported feeling deceived by their doctors. Overall, the women expressed the belief that care providers should be required to offer all the pertinent information about hysterectomies and alternative treatments prior to the procedure. The research investigates an under-researched area, and its results highlight the significance of informed consent, which is why it can be used to advocate for the introduction of informed consent laws, promoting the positive social change that would benefit the women of the US.

Acknowledgments

Foremost, my special thanks go to my immediate supervisor for the valuable and constructive suggestions from the planning to completion stages of this study. In particular, the willingness to offer time so generously has been highly appreciated. I would also like to express my deep gratitude to my research supervisors for their patient guidance, enthusiastic encouragement, and useful critiques of this research work. In addition, I would also like to thank the department for continuous advice and assistance in keeping my progress on schedule. I would also like to extend my thanks to the department library assistances for their help in my search for the secondary resources that were helpful in completing my study. Finally, I wish to thank my friends and relatives for their support and encouragement throughout my study

Introduction to the Study

The study focuses on women who have undergone a hysterectomy in Mississippi without comprehensive informed consent. The comprehensive informed consent law aims to provide women with an opportunity to understand the alternatives that are available for hysterectomy. Eysbouts et al. (2017) purported that the patient and surgeon should have shared decision making, which includes an understanding of the procedure, alternatives, potential risks, and complications. A comprehensive informed consent law is a method of ensuring appropriate and adequate patient knowledge with regard to hysterectomy during the decision-making process (Eysbouts et al., 2017). Hysterectomy is a complicated surgical procedure that may result in serious damage to a woman’s reproductive system (Meij & Emanuel, 2016). In some severe cases, fatalities can occur as a result of a hysterectomy (Meij & Emanuel, 2016). The comprehensive informed consent law is aimed at providing women with more information concerning various options for treatment (Burgart et al., 2017). This study is critical in understanding the feelings and experiences of women who have undergone the surgical procedure without the comprehensive informed consent law, not only in Mississippi but also across various states in the United States.

In this chapter, I provide a brief summary of the literature and describe the gap in knowledge on the concerned topic in the background. In addition, this chapter includes the research problem and provides a clear statement that connects the problem addressed and the focus of the study. Finally, the chapter includes the research questions as well as the theoretical or the conceptual framework on which the study is based.

Background of the Study

Clinical problems causing hysterectomy are the women’s major health issue (Meij & Emanuel, 2016). However, cases of hysterectomy are more prevalent among minority women. Researchers have indicated that about 23% of women of Native origin undergo hysterectomy, which is significantly higher than the corresponding rate among non-Hispanic white women (Collins et al., 2014). However, the cases of hysterectomy only minimally can be compared with other procedures for addressing women’s health problems, such as ovarian cancer surgery. Also, researchers have indicated that in the United States, women undergoing the surgical procedure are twice the number in the UK and Sweden (Abdulcadir, Tille, & Petignat, 2017). Further, researchers have indicated that about 25% of women in the United States have undergone surgery due to reproductive complications, such as severe vaginal bleeding, uterine fibroids, and cervical cancer (Abdulcadir et al., 2017). The reasons why women undergo a hysterectomy are diverse, ranging from the relief of pain to the removal of fibroids.

While hysterectomy is not new, it is widely applied without a legal framework for doctors to provide information concerning alternative and safer treatments (Sandberg et al., 2017). Only New York, Washington, and Pennsylvania have established comprehensive consent statutes that act as protection against potential dangers of hysterectomy (Rizk et al., 2014). Most U.S. states lack a policy framework offering physicians an increased opportunity to provide information and enhance the understanding of alternative and safer treatments.

Corona et al. (2015) provided alternative surgical procedures, of which women who undergo a hysterectomy are typically unaware. However, doctors are expected to provide patient education to ensure those female patients have the required knowledge. The comprehensive informed consent law mandates that doctors disclose all information on hysterectomies, including alternative treatment options. The disclosure would provide women with a wide variety of treatment choices (Corona et al., 2015). Using secure procedures can be used to encourage patient education, such as using encrypted emails which contain information about all therapeutic procedures regarding hysterectomy (Tapper et al., 2014).

The purpose of comprehensive informed consent is to authorize the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to issue a pamphlet containing information concerning hysterectomy and other therapeutic alternatives (Eysbouts et al., 2017). However, few studies have been conducted on women who undergo hysterectomy without information in relation to alternative treatments. Therefore, this study will fill the missing data on the study of hysterectomy as it relates to the lack of policy and comprehensive consent statutes that allow medical practitioners to provide information regarding safer treatment alternatives.

Problem Statement

One out of ten women who undergo a hysterectomy may suffer complications arising from the procedure (Eysbouts et al., 2017). Due to the high probability of complications associated with this procedure (approximately 13%), women should only undergo hysterectomies in life-threatening cases like uncontrollable bleeding, complications arising from childbirth, and severe infections (Eysbouts et al., 2017). A significant number of hysterectomy cases recorded in the United States annually are the result of localized illnesses (Eysbouts et al., 2017). Some states have instituted laws aimed at educating women about the potential risks of undergoing hysterectomies. New York has a documented informed consent law that seeks to protect millions of women who are potential candidates of the hysterectomy procedure (Lee, Gurr, & Van Wye, 2017). This study explores the lived experiences of women who have been given the hysterectomy recommendation and undergone the procedure in Mississippi, a state without an instituted comprehensive informed consent law.

Increased complications rates are associated with hysterectomy. In fact, researchers have indicated that a large number of women who undergo the procedure develop postoperative complications (Harris et al., 2017). However, this includes nongeneralizable information. The most common indications for hysterectomy are fibroid-related menorrhagia and uterine bleeding (Harris et al., 2017). Harris et al. (2017) also found that patients with the malignant disease are more likely to develop intraoperative complications compared to patients with benign growths. Postoperative complications are prevalent in abdominal surgery compared with vaginal surgery. Severe uterine complications normally exacerbate the problem (Antero, Shah, Burn, Hallisey, & Greene, 2016). Brown (2017) argued that despite the medical significance to women, hysterectomy is still a controversial issue. Further, Brown observed that the surgical procedure and its role in women’s healthcare are disputed. Despite the effects and advancements in medical practice, the procedural choice of a particular hysterectomy is not normally based on evidence, rather on the personal notion.

Despite the frequency of hysterectomy, 47 states have not enacted consent laws aimed at providing more information concerning various options to the surgical procedure (Meij & Emanuel, 2016). To that end, legal frameworks aimed at educating women concerning the potential safer alternative therapies are lacking. There exists a deficiency in the study of hysterectomy as it relates to the policy and comprehensive consent statutes (Pallett, Phippen, Miller, & Barnett, 2016). As a result, there is a lack of comprehensive informed consent law aimed at providing women with the opportunity to understand the alternatives that are available for hysterectomy.

Previous researchers have focused on issues concerning the consequences of the surgical procedure. Recently, researchers have indicated that the decisions of women undergoing the surgical procedure differ greatly between the states that have enacted the comprehensive informed consent statute and those that lack the law (Lubotzky, 2017; Meij & Emanuel, 2016). Even though the study focuses on the case of Mississippi, the research provides data that will be applied generally in all states that have not enacted the comprehensive informed consent law.

The Purpose of the Study

In this study, I explore the decision-making processes of women in Mississippi who have undergone a hysterectomy in the absence of comprehensive informed consent. In particular, I examine the attitudes and beliefs of women in Hinds County, Mississippi, who have undergone hysterectomy without any comprehensive law concerning their informed consent. Additionally, I identify the perceptions and new ideas emerging from the lived experiences of women who have undergone a hysterectomy in the absence of comprehensive informed consent law. In this study, I utilize the health belief model (HBM) to explain the behavioral aspects of patients based on the principles of individual perceptions. In addition, I primarily apply the phenomenological approach, which is utilized extensively to gather more information concerning individual perceptions through qualitative research methods (John, Malekpour, Parithivel, & Goyal, 2014). Because the main purpose of the study is to examine the beliefs and attitudes of women in Hinds County, the study fully utilizes interviews to gather the information. The interviews focus on the participants’ personal experiences and detailed accounts of the occurrences of women who have undergone a hysterectomy in the absence of comprehensive informed consent.

Research Questions

The following research questions guided this study:

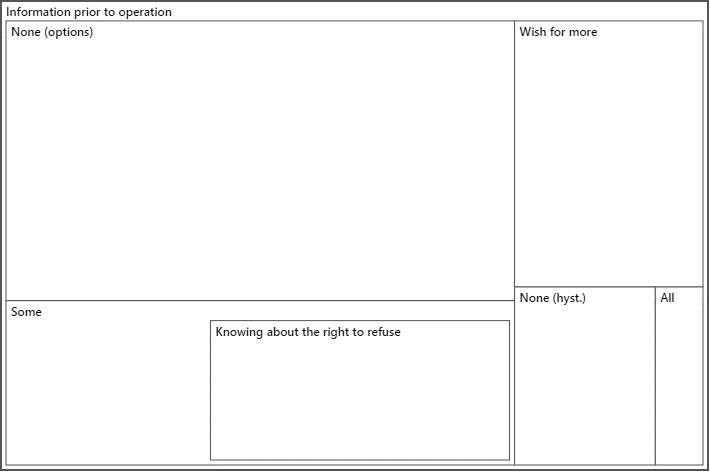

- What are the perceptions of women who have undergone hysterectomy without prior awareness of comprehensive informed consent, which includes other treatment options?

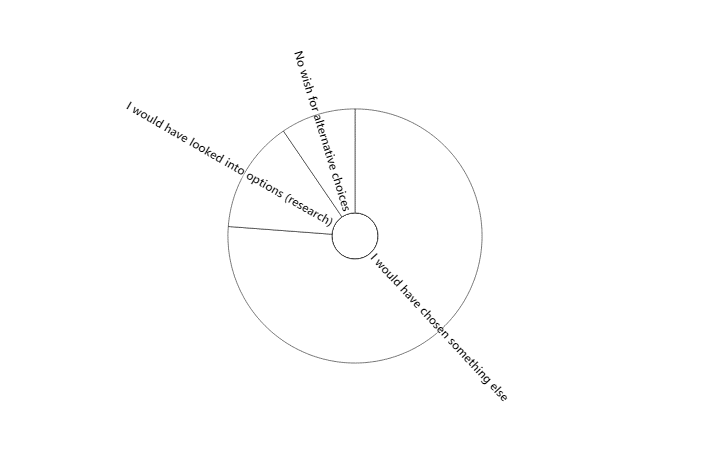

- What are the themes that emerge from the lived experiences of women who have undergone a hysterectomy in the absence of comprehensive informed consent law?

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework of this study is based on the HBM. This model was originally developed to explain why patients fail to participate in preventive care and treatment (Rosenstock, 1974). The HBM is one of several behavioral theories that have been used to help explain individual health-related behavior based on several principles. The principles of this model imply an individual’s perception of their ability to manage the disease, their understanding of the magnitude of its effect, and the efforts required to alter their behavior respectively (Lambert, Azuero, Enah, & McMillan, 2017).

The HBM purports that an individual makes decisions regarding health behaviors (surgeries, preventive care, and follow-up treatment) based on perceptions. Adequate patient education aids in making an informed choice regarding health behaviors and is an important part of how the behavior is perceived (Goodman, 2016; Lambert et al., 2017). The HBM will help address the lived experiences of women who have undergone hysterectomies in Mississippi by exploring how the absence of the comprehensive informed consent law affected the participants’ decisions to undergo the surgery. The HBM is useful in answering the research questions and uncovering themes related to the common phenomenon experienced by the subjects.

The theory is based on the principle of individual perception of personal health-related issues. The model asserts that individuals make decisions based on perceived medical care (Corace et al., 2016). According to Huber and Tu-Keefner (2014), HBM has been widely applied in various fields within the health sciences to explain human behavior. The model is useful in answering the research questions and uncovering new areas that relate to the common incidents the participants experienced.

Nature of the Study

This study is qualitative in nature. Qualitative study approaches aim to investigate the interpretation individuals give to a social or human problem (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). Thus, this study is focused on the attitudes and beliefs of women in Hinds County, Mississippi who have undergone hysterectomies without the presence of comprehensive informed consent law. It has been necessary to recruit subjects who have at least a high school diploma (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). In this way, it can be assumed that the subjects have comparable perceptions of informed consent. They are more likely to act similarly in a medical setting. Much attention should be paid to the patients’ abilities to understand informed consent. In particular, one should ask several questions about the legal consequences of signing informed consent documents. This precaution can help the researcher to understand the perceptions and attitudes of respondents. Admittedly, the study may become more time-consuming; nevertheless, by asking these questions, one can gain better insights into the decisions of the patients (Creswell & Creswell, 2017).

The study design approach that best suits the study is the phenomenological approach. Phenomenological approaches are utilized to illuminate and identify phenomena by deciphering how they are viewed by individuals in a situation (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). It is applied in the human sphere to gather deep information and perceptions through qualitative research methods. The methods could be interviews, observations, and discussions among others (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). Specifically, the approach focuses on the study of experiences from the perspective of actors.

Due to its extensive application as a qualitative interview technique in the social and health sciences, this approach would allow the structuring of interviews with predetermined questions (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). A comprehensive interview protocol is administered to the study participants selected from members of a support group in Hinds County, Mississippi. The questions that are used to obtain crucial data are designed and administered with the help of face-to-face interviews. The interview questions were designed based on the reviewed research findings related to the topic and were intended to cover the prevailing identified themes and knowledge gaps including the awareness of alternatives to hysterectomy, effects of the procedure on women’s quality of life, perceived risks, and benefits, possible complications, and some other issues.

The questions that are used to acquire crucial information for further analysis would be modified when necessary to reflect the dynamics of the study. Creswell and Creswell (2017) assert that phenomenological research commences with detailed descriptions of lived circumstances, most often first-person accounts, organized in everyday language that avoids the use of scholarly and theoretical terms. The approach enables the researcher to gather a detailed account of the lived experience of women who have undergone hysterectomies. The approach aims to reduce the participants’ personal experiences with a phenomenon to a representation of the shared core (Creswell & Creswell, 2017).

Piloting the Questions

The interview questions have been piloted among a group of participants. Thus, the efficacy of the interview as the tool for obtaining the necessary data is defined. For instance, the possibility of overlooking essential information during the interview or focusing on the information that is not necessary for the research has been detected and addressed respectively. Thus, the questions may undergo certain changes based on the outcomes of the pilot.

Definitions

- Hysterectomy: A surgical procedure to remove the uterus (Lambert et al., 2017).

- Mortality: The state of being susceptible to death (DeJohn, 2014).

- Cyst: A pocket of human tissue (Zhang et al., 2014).

- Antisepsis: A medical practice of using antiseptics to eliminate disease-causing mechanisms (Zhang et al., 2014).

- General anesthesia: A medical treatment that puts patients into a deep sleep to help them avoid pain (Zhang et al., 2014).

- Informed consent: The approval given by a patient for a particular medical intervention implies that a patient provides a healthcare provider with the authority to make decisions regarding the management of the patient’s health (Lambert et al., 2017).

- Comprehensive Informed Consent Law: An all-embracive system of regulations providing women with an opportunity to choose whether to give permission for a hysterectomy, as well as a chance to learn about alternative treatment options (Zhang et al., 2014).

Assumptions

Interviews are the main data collection technique. Based on this research instrument, we assume that the respondents would answer the questions truthfully. Similarly, since a specific research sample is used, we assume that the sample would be representative of the views of women who have undergone a hysterectomy in Mississippi. However, to overcome this assumption, the methodology of this paper includes a snowball sampling technique to make sure that the sample chosen represents the desired demographic.

Scope and Delimitations

Delimitations of a study refer to issues that are within the researcher’s control. The geographical region covered by the study is a delimitation of this study. In this study, the experiences of Mississippi women who have undergone hysterectomy are covered. Another delimitation of the study is the selection of the respondents for the interviews as the main reference point for gathering information concerning the experiences of women who have undergone hysterectomy (Grove & Gray, 2015).

Limitations

Study limitations refer to issues that are out of the researcher’s control (Creswell & Poth, 2016). In this study, time is a significant limitation in particular, during the data collection process where the interviews may be restricted depending on the time allowed by the respondent. Another limitation is the demographic of the analysis. While the study would have been better conducted in large and diverse female populations, the study is restricted to only a few women in Mississippi. The study is mainly focused on sampling the views of Mississippi residents. Therefore, the findings of the study retain their generalizability.

Significance

This study is significant because it focuses specifically on the decision-making process of women in Mississippi who have undergone hysterectomies in the absence of comprehensive informed consent law. By focusing on the lived experiences of this population, this study brings insights into the perceptions of participants’ abilities to make patient-centered decisions related to their health outcomes. Hence, the study’s findings have the potential to bring about a positive social change in women (Grove & Gray, 2015).

This research can lead to the improvement of health services. In particular, medical workers such as nurses and physicians can better understand the experiences of women who underwent hysterectomies. Thus, healthcare professionals can better educate these women who may not easily cope with the effects of hysterectomy. These women often find it difficult to adjust to the problems originating from this surgery (Reis, Engin, Ingec, & Bag, n.d.). This is why the educational assistance of medical workers is of great value to them. This is one of the benefits that this study may bring.

Additionally, by understanding the challenges faced by these women, medical workers can better explain the options that are available to women who may need to undergo a hysterectomy. In particular, they should fully understand the effects of this surgery on the health of a woman. This is another example of a positive social change. Furthermore, this study can demonstrate what particular issues are most pertinent to women who may need to undergo a hysterectomy. By using the findings of the study, medical workers can help patients make informed decisions. This is one of the positive social changes that should be considered (Reis et al., n.d.).

Moreover, it may be necessary to provide counseling to women who underwent this surgery in the past. This type of assistance can also be viewed as one of many health services. In turn, the results derived in the course of this study can assist such counselors who will be able to work more effectively. Thus, one can say this research can eventually promote the practices which can improve the experiences of many individuals whose needs could have been previously overlooked by medical professionals (Reis et al., n.d.).

Data from this study may inform legislatures regarding the need for a comprehensive informed consent law that provides clear guidelines for both patients and physicians. Because some patients do not understand surgical procedures and associated risks, informed consent is fundamental in healthcare. It signifies the physician is speaking to a patient in simple terms that the patient understands, as well as disclosing all pertinent information and dangers. As a result, the patient understands that surgery is a choice (Pop-Vicas, Johnson, & Safdar, 2017). Standards of care are established in guidelines and in the medical evidence and patients have a right to know all reasonable alternatives consistent with high-quality medicine (DeJohn, 2014).

The findings of this study contribute to existing academic knowledge regarding hysterectomy and the absence of informed consent when undergoing such procedures. Policymakers and health practitioners would also find this information useful in developing policies and procedures that guide this health process. This way, they will have a proper guiding framework for the development of informed consent law in Mississippi and around the country. With law guiding informed consent, women will be able to undergo hysterectomy fully aware of the procedure and the consequences.

In addition, women will be capable of making decisions based on the disclosed information. As a result, women will have various treatment alternatives as indicated in the booklets.

Summary

This chapter highlights the nature of the study and sets the tone for the rest of the dissertation. It shows that the researcher explores the lived experiences of women who have undergone hysterectomy without informed consent. The findings of the study will add more knowledge to existing literature. Similarly, policymakers will use the study findings to understand the importance of informed consent law when undertaking medical procedure.

Literature Review

This chapter evaluates previous research studies that have explored the intrigues surrounding women who have undergone hysterectomy without informed consent. It highlights the key variables and concepts surrounding the medical procedure and the different ways that researchers have approached the issue. This way, it is easy to understand the major theoretical composition of the research issue and any major hypothesis that may arise from the same.

Literature Search Strategy

The information included in this study has come from credible sources primarily from previous studies. Most importantly, there has been a keen focus on previous studies published in books, journals, peer-reviewed articles, and credible websites. Some key databases consulted include emerald insight and sage journals. In addition, Cochrane menstrual disorders (CMD) and Subfertility Group Trials Register (December 2009 to January 2014) were searched. Besides, the following health sciences electronic databases were searched into including CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 12), CINAHL Plus (January 2009 to January 2014), MEDLINE (January 2009 to January 2014), Health and Medical Complete (January 2009 to January 2014), EMBASE (January 2009 to January 2014), and PsycINFO (2009 to January 2014). Key search terms included “hysterectomy,” “Mississippi,” “Health Belief Model,” and “informed consent.”

Theoretical Foundation

As highlighted in the first chapter, the HBM model outlines the main theoretical foundation of this paper. This framework guides the research process outlined in this paper by narrowing down our focus to behavioral responses and perceptual influences about hysterectomy. Researchers such as Loke, Davies, and Li (2015) have used this theory to investigate the behavioral patterns of patients based on perceptual responses to policy and environmental issues.

Literature Review Related to Key Variables and Concepts

Historical

Hysterectomy has its origin in prehistoric times, with the first operation performed as early as 120 AD by Soranus in Greece. Alsaharavius, a physician in the 11th century, made a commentary about a surgical excision of the uterus. Vaginal hysterectomies had been performed in the middle ages, as revealed by some medical writings (Deffieux, Vinchant, Wigniolle, Goffinet, & Sentilhes, 2017).

In 1809, Ephraim McDowell performed the first abdominal hysterectomy on Jane Todd Crawford, who had a massive ovarian cyst weighing 10.2 kilograms. It took McDowell 25 minutes to remove the left tube and the ovary, while outside his house townsfolk were building gallows for him in case the patient would die. Five days later, Jane Todd was well and up in McDowell’s house and after 20 days, she went home to Greensburgh, Kentucky. At that time, surgeons operated without anesthesia, antisepsis, or antibiotics, and the patient was allowed to recite the psalms to slightly ease the pain. McDowell performed 13 hysterectomies in the course of his practice, with only one death. It was an extraordinary feat considering that sepsis and peritonitis were complications after laparotomy (Deffieux et al., 2017).

Charles Clay came up with the word ovariotomy. On September 13, 1842, he removed a 17 pound, 5-ounce ovarian tumor, with the patient having brandy and milk for analgesia. When anesthesia was discovered, Clay did not want to apply it to his patients, as he considered it a distraction. He reasoned that patients who had the courage to undergo surgery without anesthesia were imbued with a strong will to live (Aarts et al., 2015; Morice, 2014). On January 3, 1863, Clay performed the first successful hysterectomy with oophorectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy (Aarts et al., 2015).

In 1853, Ellis Burnham successfully performed a subtotal hysterectomy and the patient survived. Another surgeon named Kimball performed a deliberate but successful hysterectomy due to a fibroid tumor. Chloroform as a form of anesthesia was used during the operation. Before this time, surgeons used opiates, which contained hyoscyamus and mandragora, mixed with alcohol to desensitize patients undergoing surgery. The nitrous oxide gas was introduced which could induce amusement and euphoria and reduce sensitivity to pain. In 1831, a combination of ether, nitrous oxide, and chloroform was later used as anesthesia. Dentists used ether as dental anesthesia, and it was Oliver Wendell Holmes who first coined the word anesthesia.

Many women undergo hysterectomy for noncancerous illnesses and as a preemptive measure for ovarian cancer. Gynecological problems and cancer are the primary causes of hysterectomy (Peng, Chen, Wu, Hu, & Li, 2017). Many hysterectomy cases in the United States are the result of localized sickness, which means the sickness does not spread to the uterus, and removal of the uterus is not necessary (Peng et al., 2017).

About a quarter of women in the United States may have undergone a hysterectomy by the age of 60, whereas in the United Kingdom, the ratio is one to five women. More than 90% of those surgeries were performed for benign tumors and symptoms for uterine fibroids, vaginal bleeding, and others that are non-life-threatening (Suwannarurk, Thaweekul, Mairaing, Poomtavorn, & Bhamarapravatana, 2014). However, some women undergo complex surgeries such as the peripartum hysterectomy. Gupta and Manyonda (2014) indicated that 40% of all women worldwide will have a hysterectomy by the time they reach 64 years of age, with the primary objective of relieving pain and enhancing the quality of life. With the introduction of alternative treatment, hysterectomy has become less prevalent in most countries (Fylstra, 2015). There are still doubts surrounding hysterectomy and why women should undergo a hysterectomy. Yusuf, Leeder, and Wilson (2016) have focused on the following aspects in their study: (a) Can hysterectomy provide essential treatment for diseases in women’s reproductive organs? (b) Should other less invasive treatments are considered first? (c) How informed are women of the legal aspects of hysterectomy, particularly the subject of informed consent?

Women have to be informed of treatment options other than hysterectomy, which has complications. A comprehensive informed consent law requires physicians to provide information concerning other alternative therapy (Seagle, Alexander, Strohl, & Shahabi, 2018). The benefits of the informed consent law will allow women to decide before any treatment is performed (Seagle et al., 2018). Women should properly understand this information and knowledge of the law (Diamond, 2014).

Hysterectomy is one of the most frequently used operative techniques among many gynecological procedures. However, it is significantly decreasing because there are alternative options, and patients have reported some complications after hysterectomy (Darwish, Atlantis, & Mohamed-Taysir, 2014). Theunissen et al. (2016) found that the complexities in the surgical procedure rise when pregnancies occur. A longitudinal study found that more women who belonged to the lower socio-economic class had undergone hysterectomies than those of the higher socio-economic status. Knowledge about, and access to, other treatment may not be available in specific areas, which is one of the reasons why those who are of the lower socioeconomic status mostly undergo hysterectomy (Ogburn, 2014). Mississippi Delta Region is one of the specific areas where the socio-economic status of women is lower and accessibility to other treatment options is limited (Collins et al., 2014). As a result of the prevailing situation, women also lacked education and experienced poor nutrition as well as healthcare (Collins et al., 2014). These factors could have resulted in the lack of valuable information for women who might have undergone hysterectomies, and there was a dearth of knowledge on cancer screening and other healthcare expenses (Croce, Young, & Oliva, 2014).

Every year, approximately 600,000 American women undergo hysterectomy for non-cancerous causes (Halder et al., 2015). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014), reported that there were 5.4 hysterectomies for every 1,000 women annually during the period 2000 to 2004. However, the hysterectomy rate is decreasing in Scandinavian countries and in the United Kingdom (Schollmeyer et al., 2014).

Ovarian and uterine cancers are primary causes of hysterectomy (Singh, Ryerson, Wu, & Kaur, 2014). In a study on cervical cancer, researchers found that hysterectomy did not reduce the survival rate but provided comfort in the pelvic region. Moreover, some doctors performed a hysterectomy on complaints of endometriosis, which can be treated with analgesic therapies and other non-invasive methods (Grigore, Ilea, Terinte, Sava, & Popovici, 2014; Heng, Stephens, Jobling, & Nie, 2016).

A study on endometriosis and its effects on the quality of life revealed that this sickness impacted women’s quality of life, particularly their work, education, and home and family life (Heng et al., 2016). The effect of endometriosis on work was more pronounced with 51% of the participants saying that endometriosis significantly affected their work life. Endometriosis also affected the women’s relationships with their husbands, with some participants saying that their sickness caused the divorce. The data collected in the study confirmed the negative effects of endometriosis on women’s quality of life (Heng et al., 2016). Uterine myomata or leiomyomas are some common causes of menstrual bleeding. Approximately 30% of hysterectomies are performed due to the diagnosis of fibroids (Heng et al., 2016). Myomectomy is an alternative to hysterectomy in removing fibroids, but it requires a longer recovery period.

Meaning and Causes

Hysterectomy is a surgical method to treat gynecological problems with the aim of removing the ovaries or the fallopian tube. The removal of the ovaries or the fallopian tube may result in a menopausal period, and the woman will be unable to become pregnant. Uterus amputations do away with uterine cancer. Conversely, oophorectomies get rid of the possibility of ovarian cancer (Collins et al., 2014). Gouy et al. (2017) indicated that bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) could reduce the risk of ovarian cancer − the reason why it is performed bilaterally with some hysterectomies. While ovarian cancer can be circumvented, oophorectomy increases the threats of heart disease and lung cancer. Rimbach, Holzknecht, Nemes, Offner, and Craina (2015) also argued that the new methods of the surgical procedure could be used to avoid risks associated with the surgical procedure. Cardiovascular risks may be higher due to the reduced production of endogenous sex hormones (Hampton, 2014; Laughlin-Tommaso et al., 2016; Seki et al., 2014). A previous cohort study supported evidence on the relation of hysterectomy and cardiovascular disease in women who were less than 45 years of age during an operation (Hampton, 2014; Laughlin-Tommaso et al., 2016; Seki et al., 2014).

Relation of HRT and CHD

Some researchers have found that hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which is prescribed for women who have undergone hysterectomy, causes coronary heart disease (CHD) (Kurita et al., 2016). However, there were studies reporting that HRT users did not have cardiovascular risks, while some studies showed that the effects of HRT were not clear and overestimated (Kurita et al., 2016). Women with the uterus intact take prescribed estrogen and progestin as protection from cancer occurrence. HRT, which has a dose of progestin, can ease estrogen in controlling CHD, although there have been reported little increase in CHD in women who take the combined dosage. The study of Kurita et al. (2016) provided inconclusive evidence that HRT caused CHD but the findings also stated that HRT was associated with hysterectomy. Women who use HRT have lower levels of systolic blood pressure and low cholesterol (Kurita et al., 2016).

Techniques and types of hysterectomies

Techniques in hysterectomy include open surgery performed through the vagina or a method using laparoscopy, and the most modern, which is a robot-assisted operation (Tapper et al., 2014). Laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) is usually applied in benign and malignant tumors. Vaginal hysterectomy is used in many cases while LH is usually performed in cancer cases (Seror et al., 2014). LH can be performed vaginally, accompanied by laparoscopic procedures, or where there is no vaginal component. The American Gynecologic Laparoscopists issued a statement in 2010 that hysterectomies for benign cases should use vaginal or laparoscopic procedures because of the benefits on women (Gupt & Manyonda, 2014). These benefits include lower costs, shorter hospital stays, and quick recovery (Gupt & Manyonda, 2014). However, in a later study in Ohio by the same authors, they found that this method was associated with higher charges than the other two techniques of hysterectomy. In this same study, Gupta and Manyonda (2014) found that the rate of hysterectomy decreased due to the introduction and constant use of laparoscopically-assisted vaginal hysterectomy.

Complete hysterectomy aims for the uterus along with the cervix, while partial hysterectomy does not aim for uterus removal. Supracervical hysterectomy is performed when complications during an operation necessitate completing the required surgery as early as possible. However, supracervical hysterectomy should be planned for patients who are perceived to have higher perioperative complications.

Vaginal hysterectomy is surgery performed through the vagina wherein the surgeon conducts an operation on the vaginal wall to be able to see the ligaments and tissues of the uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes (Zafar, Iqbal, Javed, Noor, & Niaz, 2017). These organs can be removed through the vagina. Findings in randomized trials have shown that vaginal hysterectomy allows producing the most beneficial outcomes, at the same time helping use available resources sparingly to allocate them in the most efficient manner and enhance the possibility of a positive outcome (Bilandzic, Fitzpatrick, Rosella, & Henry, 2016; Koleli, Ozdogan, Sariibrahim, Ozturk, & Karateke, 2014; Loke et al., 2015).

In the total hysterectomy, the portion called the top of the vagina is closed, creating a blind pouch. In this case, intestines are placed (instead of the uterus) in the blind pouch created due to hysterectomy (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2014). An abdominal hysterectomy is performed when the woman has acquired an enlarged uterus and cancer has been diagnosed or suspected. This procedure takes a vertical incision, about 4” to 6”, along the pubic section and the navel (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2014). With respect to morbidity and mortality, the research found complications in 44% for abdominal and 27.3% for vaginal hysterectomies. A Cochrane study found fewer infections and rapid recovery attributed to vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomies than an abdominal hysterectomy (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2014; Gupta & Manyonda, 2014).

Hysterectomy is most necessary when pain cannot be controlled due primarily to fibroids, or pressure, and severe bleeding. It can be applied to postmenopausal women who might have malignant tumors and for symptoms of endometriosis that cause pelvic pain, pain during intercourse, and when there is extreme bleeding (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2014). Hysterectomy is an effective treatment for menometrorrhagia, leiomyoma, and symptoms associated with postmenopause. Women that have not been associated with the ovarian disease would not have their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed. In such women, the production of hormones would be normal even if they experience a lapse in their menstrual cycles. However, when they undergo hysterectomies, they will occasionally cease producing estrogen and experience the menopausal stage (Miyata et al., 2014).

Complications in Hysterectomy

Hysterectomy can lead to psychological or mental problems but some studies have found that hysterectomy provided comfort to women and improved their quality of life. However, women should seek other options before undergoing hysterectomy (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2014). The doctor and the patient should have ample discussion before proceeding, and the doctor must observe the highest ethical standards of medical practice (Miyata et al., 2014).

There are valid medical reasons for hysterectomy, but there are as many valid reasons for not performing it, which means there are other options rather than immediately subjecting the woman’s reproductive region to surgical procedures. Epidemiological studies showed that for two decades, approximately 90% of hysterectomies were done for only benign surgical reasons (Darwish et al., 2014; Laughlin-Tommaso et al., 2016). Women who undergo this surgical procedure must be informed of the reasons why it has to be done, how it should be done, including other medical options and complications in later life. Patients have to think of it and give their consent only on life-threatening conditions (Darwish et al., 2014).

Due to the results of the various studies, the medical profession has raised concerns over the long-term effects of hysterectomy. For example, there has been reported one complication for every 574 surgeries performed in the United States (Brohlet al., 2015). Additionally, studies have found that women who had bilateral oophorectomy had a 17% risk of having heart disease and a 28% risk of succumbing to death due to complications. Lung cancer was also one of the complications (Brohl et al., 2015). Moreover, it has been proven that hysterectomy with oophorectomy affects the development of menopause. Particularly, women have menopause 3-4 years earlier than expected, which is the reason for their blood supply disturbance in the ovaries and can have a detrimental effect on patients’ cognitive functions (Kurita et al., 2016). Some studies also found that women who had undergone premenopausal bilateral oophorectomy showed signs of reduced cognitive functions, but those taking HRT reported improved cognitive functions. The reported dementia because of hysterectomy is still unexplored, but a longitudinal study of homozygous twins who had undergone hysterectomies showed symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (Kurita et al., 2016). Emre, Akbulut, Yilmaz, and Bozdag (2014) reported numerous deaths because of hysterectomies.

Some studies reported major complications in urinary incontinence (loss of control in urination) and bowel dysfunction, which occur in old age and affect women’s quality of life. However, the study of Emre et al. (2014) on a few randomized clinical trials focusing on the relation of hysterectomy and urinary incontinence provided inconclusive evidence. Randomized clinical trials indicated that the studies had little evidence to offer because only a few cohort studies were conducted. Despite little evidence of cohort studies, Saito et al. (2014) still concluded that urinary incontinence and bowel dysfunction were complications for hysterectomies when women reached old age. Emre et al. (2014) supported this finding when they researched urinary incontinence through Medline articles, using search words, and found that women who had a hysterectomy were 40% higher in acquiring urinary incontinence at later life than women who had not undergone hysterectomy (Emre et al., 2014). Other complications included occasional fever, hemorrhage, and other life-threatening events (Emre et al., 2014).

Pelvic floor dysfunction is a common problem of women who are at the menopausal stage (Wright et al., 2014). Uterine problems can greatly affect women’s social lives, especially in this age of globalization where women have vast roles in society. Hysterectomy can relieve symptoms that have interfered with their daily activities. Studies indicate that over 40% of women who have their ovaries removed have a decreased degree of depression. Moreover, women having a positive perception of their social support network in both pre and post-hysterectomy indicate increased chances of having a better quality of life. Physical complications in hysterectomy include edema and swelling in both legs. Long-term physical effects include numbness, tingling, and limited movement of the legs.

Another factor that affects women undergoing hysterectomies is inequities. Studies have found evidence of inequities for women, which need to be addressed by healthcare professionals for a corresponding intervention. The team should determine the psychosocial drawbacks of hysterectomies and meet the psychological needs of women.

There are cases where hysterectomy is necessary, such as the occurrence of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), which is related to birth events threatening a mother’s life that affects her adjustment to motherhood (Vijaya, Patel, Purushothama, Mallesh, & Nagara, 2015). Severe PPH is described as blood loss equivalent to about 1,000 milliliters right after giving birth until weeks postpartum (Power, Jackson, Carter, & Weaver, 2015). There are cases where PPH needs an emergency hysterectomy to control the bleeding (Power et al., 2015). PPH and subsequent hysterectomy are two difficult situations that a mother should be able to adjust to after giving birth.

Power et al. (2015) conducted a study on perspectives of early mothering by describing their adjustment and recovery from an emergency hysterectomy after a severe PPH. During the recovery period, the mother may be separated from her baby, as she has to be admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for observation and careful recovery (Power et al., 2015). During this time, the mother may experience guilt feelings, shame, and failure. In Australia, the incidence of women admitted to ICU after birth is 1.84 to 2.6% of all pregnant women (Power et al., 2015). UK has a significant number of pregnant or postnatal women admitted to ICU (Power et al., 2015).

On the relation of hysterectomy and breast cancer rate, the study by Gaudet et al. (2014) found no relation between breast cancer rate and simple hysterectomy. However, the researchers found that risk factors for hysterectomy were also common risk factors for breast cancer. This meant the conditions were similar for both illnesses, but there was no relation between hysterectomy and breast cancer.

An analysis of hysterectomy performed for the benign disease was conducted at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel, Germany, in which the data were taken from hospital records. The causes for surgery included fibroids and precancerous abrasions of the uterus (Schollmeyer, et al., 2014, p. 45). The techniques used in the various operations included vaginal hysterectomy, abdominal hysterectomy, TLH, LSH, and laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH). Only 766 patients qualified for the criteria of the study. The common cause for hysterectomy was uterine myoma, which accounted for 58.6% of the study. Vaginal hysterectomy was the common technique used for uterine prolapse. In the study period, the researchers found no mortalities for hysterectomy for benign reasons but there were 52 (5.5%) cases, which had complications out of the total 953 operations. For the period 2007 to 2010, the numbers of abdominal hysterectomy and vaginal hysterectomy decreased due to the increase of laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) and total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH).

Some studies found symptoms of psychological co-morbidity due to hysterectomy, which can result in negative feelings about body image, sexual orientation, youth, energy and physical activities, and reduced child-bearing ability (Darwish et al., 2014). However, in conducting a meta-analysis of the different studies and articles on hysterectomy, Darwish et al. (2014) found that hysterectomy performed for benign gynecological conditions was positively associated with depression or anxiety outcomes. Moreover, long-term studies suggested that women returned to their physical and psychological functioning after hysterectomy. Darwish et al. (2014) study further found that hysterectomy, no matter what type and technique used, had improved the quality of life and psychological outcome of women. There was a reduction in the symptoms of depression and depression scores compared to the preoperative indications. This suggests that women usually felt comfort after the non-malignant indications were removed due to hysterectomy. Sexual pleasure, arousal, and desire improved after hysterectomy, regardless of the surgical technique used (Darwish et al., 2014).

Impact of Hysterectomy on Women’s Lives

In other cases, hysterectomy creates psychological problems such as depression and low self-esteem, and negative outcomes on patients’ social lives. Power et al. (2015) indicated that women feel intense pain right after hysterectomy. In their research, Power et al. (2015) studied 27 women experiencing abdominal or vaginal hysterectomies, with their mothering capacity being the key inclusion criterion. The researchers found that hysterectomies limited their physical activities while others felt the experience was worse than a caesarian section. A cesarean section accompanied with hysterectomy requires time to recover, as this may result in emotional, physical, and psychological stresses (Power et al., 2015).

Hysterectomy without ovary removal is a different case. It has been argued that hysterectomy does not greatly affect women when the ovaries are not removed. However, quality of life should be considered when determining the effects of illness. Quality of life is linked with the individual’s sense of comfort and happiness in life. Studies in Taiwan and Turkey have found that women regard their uterus as the embodiment of femininity and maternity. As a result, the loss of a uterus is viewed as the failure to fulfill their purpose as women (Pendleton et al., 2016). In the study on women who have undergone hysterectomy, Pendleton et al. (2016) found that hysterectomy adversely affects patients’ body images, self-respect, and matrimonial status.

In order to answer the various concerns about the overuse of hysterectomy, scholars from the University of California at San Francisco conducted a study on hysterectomy and other treatment options and their impact on women’s quality of life. The study employed 63 participants, aged 30 to 50, who were suffering from excessive bleeding for four years. The women took synthetic progesterone treatment, but this was unsuccessful. The researchers recommended a hysterectomy to a group of participants and some to hormonal medication or birth control pills. The researchers asked the participants of their opinion about the quality of life, their physical and mental conditions, and their feeling after hysterectomy. After a period of six months, the participants who underwent hysterectomies reported reduced abnormal bleeding and had improved sleep and quality of life, including overall health and wellbeing. Seventeen of the 32 members of the medication group opted to have a hysterectomy and reported improved well-being. However, the participants who did not undergo hysterectomy also reported improvement in their quality of life (Brohl et al., 2015).

Additionally, in a 2000 survey of women who have undergone surgery, the researchers found that respondent women reported improved sexual functioning (Ogburn, 2014). A randomized survey in 2007 by “BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology” supported this finding, wherein respondents who had hysterectomy reported enhanced sexual functioning than they had before they underwent hysterectomy (Ogburn, 2014). In a report by the Maine Women’s Health Study, many women indicated that they were satisfied with the result of a hysterectomy. In a study on women aged 25 to 50 who had either hysterectomy or noninvasive treatments for benign tumors, fibroids, abnormal bleeding, and pain in the pelvic region, Dr. Karen Carlson of the Women’s Health Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston found positive perceptions of hysterectomy. The respondents reported that hysterectomy relieved their gynecologic problems and that their physical and mental health improved. A small percentage of the population indicated that they lost libido and had little sexual enjoyment (Ogburn, 2014).

Women and Informed Consent Law

It is noteworthy to provide some actual cases of hysterectomy in this section to define the impact of this medical practice on women’s lives. Ogburn (2014) underwent surgery to get rid of a benign cyst but later found out that the doctor who operated on her also removed the uterus and ovaries. It was a traumatic experience for this woman that led her to some unexplored activities as a woman and as a health activist later on. Ogburn (2014) then founded a not-for-profit foundation known as the “Hysterectomy Educational Resources and Services Foundation” (HERS) to provide valuable information for women who might experience non-life-threatening medical situations and the benefits of an informed consent law before they undergo hysterectomy (Ogburn, 2014).

Roth and Ainsworth (2015) provide another case involving an imprisoned woman who was rushed to a hospital for an emergency appendectomy. During the operation, the surgeon found severe endometriosis. A gynecologist was asked to give an opinion and she concluded that the best option was to remove the fallopian tubes and the ovaries. Discovery revealed the patient had a bilateral ovarian cystectomy for endometriosis but was not informed that it would create a serious problem in the future. The patient was completely depressed to learn that she had lost her reproductive organs. The endometriosis was so severe that the patient would not have a chance of natural conception and the cysts should be removed. The review also concluded that new consent forms should have a space in which patients can designate procedures that they do not wish to be done. According to Roth and Ainsworth (2015), some women who awoke finding that they had lost their womb and reproductive organs considered their situation as a violation of their physical integrity. These women believed that the time for consulting and thinking over the choice of a procedure is important because even a short postponement of the surgery can allow women to estimate all the risks they may face. Thus, the patient should have time to think about her situation and all information should be provided to her.

The Sarah Lee Brown Case

In 1987, a case involving Sarah Lee Brown and Dr. John Mladineo became the subject of a legal battle over medical malpractice (Brown v. Mladineo, 1987). Instead of only the tumor that was to be removed, Dr. Mladineo performed a complete hysterectomy on Ms. Brown (Brown v. Mladineo, 1987). After a week of discharge from the hospital, Brown complained of excreting bodily waste by way of her vagina (Brown v. Mladineo, 1987). When the doctor was informed of Brown’s complaint, he advised the patient to take a peculiar treatment – drink some vinegar (Brown v. Mladineo, 1987). Brown was admitted to the same hospital where Dr. Helen Barnes treated her for a rectovaginal fistula, which was caused when Dr. Mladineo performed the surgery and accidentally created a canal in the rectum to the vagina (Brown v. Mladineo, 1987). This case would not have happened if there had been an adequate informed consent law regulating surgeons before performing a hysterectomy.

Comprehensive Informed Consent Law

During the days of slavery in America, black women were subjected to sterilization because they were deemed unworthy to provide offspring. This was known as the “Mississippi Appendectomy”. In the 1950s, black women were provided with contraceptives so that the black population would not grow.

It is a different environment today. A woman’s reproductive decisions are protected under the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Court decisions support the principle that reproduction is part of the very essence of human identity and reproductive choices are regarded as irrefutable rights as they are defined in the 14th Amendment, which should not be bypassed by any government agency or regulation (Ross, 2018). Although Supreme Court jurisprudence states that the right to reproduce includes using contraceptive medications, as well as having an abortion, and the right to refuse to be sterilized (Skinner v. Oklahoma, 1942), law scholars and practitioners contend that these rights should extend to the areas of reproduction and child bearing decision-making. Birth decision making and procreation are personal choices that are supported by public policy, husbands’ and wives’ testimonies on the meaning of such choices, and the social consequences of those choices.

However, Purcell, Cameron, Lawton, Glasier, and Harden (2016) argued that reproductive choices are usually made with the influence of a doctor in the hospital, supported by government funding and legislative mistake. The state regulates and controls reproductive choices based on its policy of promoting public health despite the constitutional provision that protects such choices (Purcell et al., 2016). In a country that has a comprehensive informed consent law, a woman with problems in the reproductive organs is given the option to choose. The doctor must explain the various reasons, but the woman must have the final choice. Other states have passed their versions of the law. North Carolina enacted the Woman’s Right to Know Act (WRKA), which provides that women should be provided necessary information before they decide to have an abortion (Arrigo & Waldman, 2014).

The traditional practice of hospitals is that when a patient is scheduled for surgery, she is required to sign a consent form. The form contains provisions where the surgeon is authorized to perform further surgery where the surgeon thinks necessary. In this case, there should be an open discussion with the patient regarding the available treatment options. The form should not be overall consent. The patient can seek redress by asking for police assistance or directly going to court (Low et al., 2017).

Alternatives to Hysterectomy

Complications in hysterectomy force some in the medical profession to perform alternative treatment, and one of these is uterine artery embolization (UAE). According to a study, UAE provides symptomatic relief compared to hysterectomy (Brohl et al., 2015). There have been positive findings of patient satisfaction for UAE, like shorter time of hospitalization, but the patient has to go through a surgical intervention after a few years (Bruijn et al., 2017). UAE is also an effective treatment for myoma (Dueholm, Langfeldt, Mafi, Eriksen, & Marinovskij, 2014).

There are other alternatives to hysterectomy provided by the medical profession. For menorrhagia, women are now aware of the other treatment options. Endometrial ablation, which targets the lining of the uterus, is simpler to perform with fewer complications than hysterectomy. The National Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Audit of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) have advised that women experiencing extreme menstrual bleeding should undergo subsequent intervention of ablative trials. NICE reported that ablation as an alternative to hysterectomy can improve women’s quality of life. If it still fails, then the patient should be advised to undergo a hysterectomy (Gupt & Manyonda, 2014; Tiwari, 2014).

A technical innovation that is gaining popularity is the use of uterine manipulator (UM) which is under the classification of minimally invasive hysterectomy (MIH). The doctor removes the uterus by way of the vagina, improving exposure in the pelvis and increasing the length between the urethra and the operative field (Zhang et al., 2014). One problem with MIH is when the UM disseminates cancer cells, although this is still a debatable one because of the lack of empirical studies regarding this issue (Ringash et al., 2017; Yildirim et al., 2014). The surgeon inserts the manipulator which increases intrauterine pressure when the balloon is inflated. This can enhance lymph vascular space invasion (LVSI) or enhance the passage of malignant cells through the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity. Another problem with the UM is that it can disaggregate tumor cells (Yilmaz et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014).

An alternative to hysterectomy for women with excessive menstrual bleeding (that is not due to cancer, fibroids, or endometriosis) is “balloon ablation” which destroys the endometrium, or uterine lining but does not involve uterus removal (Zhang et al., 2014). The principle reflects that of the balloon angioplasty procedure, which also uses a “balloon” to open blocked coronary arteries (Yildirim et al., 2014). In balloon ablation, a sterile solution is attached to the balloon so that it coincides with the shape of the uterus. Something is placed in the balloon to heat the fluid to 190 degrees Fahrenheit temperature. The heating process lasts for eight minutes. The purpose of the heating process is to destroy the endometrial tissue that touches the balloon (Zhang et al., 2014). The final stage consists of deflating the balloon, draining the fluid through the catheter, and removal of the catheter (Yildirim et al., 2014).

Reducing Variations in Surgery

Doctors can reduce variations in surgeries for ethical and economic reasons. Reducing variation can help myriad patients and reduce mortality and unwarranted use of resources. Patients can have other choices if the surgery can offer no benefits. Sanchez, Barach, and Johnson (2017) suggested that patient autonomy can reduce variation. However, reducing variations should be assessed by health experts who have a broad and clear interpretation of the facts in a particular case. The doctors involved should conduct further investigation if a proposed hysterectomy case is cleared with the patient or not. There should be sound evidence to provide a surgical intervention that is effective for such a disease (Sanchez et al., 2017).

Apart from the value, causes of variation include the factors associated with the delivery system, and are linked closely to cultural beliefs, and are affected significantly by the presence of casemix-adjusted data. With the application of the decision pathway, one can alter surgery processes to a considerable extent (Sanchez et al., 2017). Medical reports have noted lower deaths and complications than a few decades ago because of surgery (Sanchez et al., 2017).

Studies suggest that signs for an operation are difficult to discern in surgical guidelines and many published material only point to patient care after the decision for an operation has been made (Sanchez et al., 2017). Indications for hysterectomy have been much abused because these were not clear, which means hysterectomies were conducted without substantial reasons or causes for why they should be performed (Sanchez et al., 2017).

Evidence about the benefits and risks of surgery is significant in the decision to reduce variations, but it is not a decisive one. Variation for surgery can be provided if there is no treatment benefit or if there is no identification of the best treatment. Some new techniques of surgical practice have been introduced, but these are incomplete and slowly implemented, which means there is still a lack of evidence for its success (Sanchez et al., 2017).

A Cochrane study on the effects of clinical decision making of passive distribution of review evidence showed that appropriate reduction in surgery rates can be accomplished with the distribution of a bulletin. Educational measures distributed to surgeons doing operations resulted in a 9% fall in the operation rate. Additionally, shared decision making, which aims to give patients balanced information and a friendly atmosphere to give them the chance to choose the right treatment that fits their values and beliefs, is an ethical priority for the doctor and can reduce unwanted variation in surgery rates (Sanchez et al., 2017).

The Principle of Informed Consent

The principle of informed consent states that doctors and other health professionals should provide information on health risks and treatment options and get their consent to proposed medical procedures from their patients (Pallett et al., 2016). Women should be legally and humanely advised before undergoing hysterectomy. Without a consent law, it is possible that some physicians will not brief their patients about the complications or treatment alternatives. Passage of law means reducing threats or health risks, and patients are protected from medical malpractice. A comprehensive informed consent law provides that doctors inform women of the parameters and consequences before they give their consent to undergo a hysterectomy. Informed consent is provided to enhance patient autonomy (Pallett et al., 2016).

Mississippi women give their consent for a surgical procedure without an informed consent law, which challenges their health and rights as women. With an informed consent law, the doctor is mandated to provide information about all treatment options and effects of hysterectomy to a woman who is about to undergo hysterectomy (Corona et al., 2015). The doctor should provide all the information, and the patient should be the last to decide with the assistance of the doctor. Pallett et al. (2016) suggest that there should be a consensus between the doctor and the patient undergoing hysterectomy. With an informed consent law, the doctor is obliged to discuss with the patient whether a hysterectomy should be performed.

Informed consent is a legal term that lays down the manner in which physicians or surgeons conduct treatment or surgeries on their patients. In the medical profession, physicians are obliged to provide an explanation on the attributes of planned therapeutic action, its diagnosis for treating the infection, its hazards, and options to the anticipated diagnosis (Ahmed, 2015). The law provides for fines and other punishments if physicians diverge from what they are supposed to observe under the law and ethical principles, based on people’s treasured worth of “autonomy” (Spatz, Krumholz, & Moulton, 2016, p. 2063). When a patient and surgeons enter into an agreement, they are governed by certain rules and ethical practices (Shen, 2015). This is one ground on which such a law should be passed in Mississippi.

The principles of medical law provide that autonomy and consent are related. The focus of informed consent is that the doctor should provide all information as this is important to the patient’s decision whether to have a hysterectomy or not (Shen, 2015). Autonomy focuses on guiding where one is going, deciding where to go and in what activities to engage. Other studies also supported the autonomy principle in the context of informed consent. Informed consent enhances the patient’s independence. Autonomy also connotes treating an individual with informed consent as opposed to James Taylor’s contention that when a patient is being treated, the well-being of that person is the primary concern (Shen, 2015).

Autonomy means the patient dictates her life’s direction. For a patient to be autonomous, specifically in her decision to undergo a medical treatment, the doctor should not stop her decision, or control her decision by selecting information about medical options. Otherwise, the doctor would compromise the woman’s decision regarding her medical treatment. All information about other treatment options should be given to her. Healthcare professionals can refrain from taking over the patient’s autonomy by providing them with all information about the alternative courses of treatment that are at their disposal, including the advantages and disadvantages of those options. Some medical scholars and researchers have recommended reducing variation in surgical procedures, which has ethical and economic effects on surgery rates. Patient autonomy can be elevated, and a woman can choose to avoid it if there are no benefits to be derived from surgery (Sanchez et al., 2017).

Although attacked on both sides, the principle of informed consent has impacted the medical profession (Pallett et al., 2016). The concept of providing necessary information and acquiring consent from the woman to be placed under the knife has become a benchmark for change from the traditional protectionist and patriarchal method of treatment and a benchmark for yearning of enhancing women’s rights. There may be shortcomings to this present trend but patients’ rights, hospital ethics, the need to provide appropriate medical information to patients, and the need to acquire patient’s consent are now ordinary procedures in medical institutions, hospitals, clinics, and doctors’ dealings with their patients (Pallett et al., 2016).

In North America, doctors performed some hysterectomies even if they were not necessary. Investigations were conducted in the United States and Canada, which found that there were unwarranted hysterectomies performed. The medical profession is not united on this medical procedure regarding the reasons for hysterectomies in women (Pallett et al., 2016).

As mentioned, there are minor and serious complications in hysterectomy. The Hippocratic code on medical ethics states that the doctor will treat the patient according to his/her capability and knowledge but not to hurt or injure the patient. Furthermore, if the patient can have a choice of another method of therapy, it is possible that the mode of therapy is less expensive than surgery (Pallett et al., 2016). The doctor has a big role to play in the woman’s decision, but the doctor can also influence the decision. This, however, depends on the provisions of the informed consent law.

Proponents of women’s autonomy argue that the woman has individual rights, more valuable than the right of the fetus. They criticize and want to be free from government regulations and doctor’s intervention on reproductive issues because this comprised women’s autonomy (Pallett et al., 2016). Others argue that women’s autonomy is weakened because they are discriminated against by men. With the principle of informed consent, any doctor who operates on a woman and removes something from the reproductive organ without the patient’s consent commits an offense like physical injury or coercion (Pallett et al., 2016). Patients’ consent is not the only thing necessary, rather, adequate information that can help in the patient’s promulgation of a logical decision should be provided by the doctor. Patients can also refuse any treatment indorsed by the doctor and the doctor can be unethical and may violate the law if he/she refused to provide information regarding the patient’s condition, including other options, risks, and complications because of the treatment (Pallett et al., 2016).

Concerned organizations have provided guidelines, which include a case-by-case risk assessment based largely on the woman’s family history. Halder et al. (2015) conducted a study on women who underwent hysterectomy for the period from 2000 to 2010 and patients who underwent bilateral oophorectomy. The study identified 752,045 women who underwent hysterectomy wherein 403,073 patients had ovarian conservation while 348,972 underwent bilateral oophorectomy. The number of ovary removal has been controlled, particularly on women ages 45 to 49.

The study of Halder et al. (2015) suggests that ovarian conservation has been increasing. Procedural factors influenced this trend, such as the type of hysterectomy, which influenced the most for retaining the ovaries. Hospital characteristics influenced about 10% in the decision to conserve the ovaries, while 5% and 3% were attributed to patient decisions and physician characteristics, respectively (Halder et al., 2015). The researchers noted the variation and grouped the participants according to age and for those who underwent vaginal hysterectomy or not. Many hospitals admitted and subjected women of this latter grouping. The percentage of ovarian conservation registered as rather high. Hospitals across the United States have chosen to tread along the path of ethical practice by performing hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy only in extreme cases. The trend for ovarian conservation is influenced by data collected by hospitals regarding the relationship between oophorectomy and coronary heart disease and possibly mortality (Halder et al., 2015).

Gender Identity

A woman’s reproductive system is associated with gender identity. When this is removed by surgical means, the woman loses herself (Meij & Emanuel, 2016). Medical sociologists argue that medical treatments like hysterectomies can affect women’s lives. When a woman undergoes a hysterectomy, she loses one part of her identity as a woman and that is menstruation. Medical sociologists contend that monthly period and female femininity are correlated positively (Meij & Emanuel, 2016). Randomized studies that have been conducted indicated that menstruation is highly recognized by women (Meij & Emanuel, 2016). Menstruation makes women different from men, and they would not like to give it up so easily through hysterectomy. Menstrual periods provide an emblematic and substance connection between women. Hysterectomy marks the end of a woman’s menstruation, which disturbs gender identity, as this is closely related to womanhood (Meij & Emanuel, 2016).

Quality of Life (QoL)

The process of healing must be in several stages. Although painful as it may be, a woman who undergoes hysterectomy becomes a new individual (Danesh, Hamzehgardeshi, Moosazadeh, & Shabani-Asrami, 2015). Healing stages must be experienced with the care and a positive attitude. The loss of one part must lead to the recovery of a new life’s horizons. Various studies indicated that women who have undergone hysterectomy should develop a new way of looking at life and womanhood.

Nursing care should be planned adequately to correspond to the various stages of the healing process. Specific nursing care should make the patient move from the stage where she was dependent through a stage where she becomes conscious, self-actualizing, and independent (Danesh et al., 2015). The first stage should involve the patient coming out of isolation. Breaking free from hiding and numbness and accepting the innermost pains are significant movements that should be followed. Second, the numbness must be resolved and transformed into feeling (Danesh et al., 2015). In fact, suffering is a part of life that sometimes cannot be avoided and acceptance of suffering is the best way to reduce the pain. Visits from a mental health nurse or a professional person who can provide meaningful counseling are essential. The next stage is releasing or emptying, which involves dealing with fear and accepting the reality of womanhood (Danesh et al., 2015). The processes of emptying are in four vital steps:

- The patient must take hold of the pain like a pack of sticks to build a fire.

- The sticks have to be held in an embrace so that the person can move across the room to the fireplace.

- When reaching the fireplace, the individual can release the sticks and let them go.

- After all the steps, the individual feels warmed and happy from the sticks she has thrown out to the fire.

The individual who has undergone a hysterectomy must embrace womanhood once again after she has suffered from the medical event (Danesh et al., 2015). Studies indicate that one can accept the fact that suffering enables one to admire life, feel compassion for others of the same fate (Danesh et al., 2015). A woman who chooses to undergo a hysterectomy must learn to endure the pain because this can lead to an improved quality of life (QoL). QoL is multidisciplinary, but its definition is not universal, as it can be seen from different perspectives (Huber& Tu-Keefner, 2014). Hysterectomy can lead to improved QoL if the woman knows how to deal with it, patiently and perseveringly. There are also several notions and concepts which are influenced by culture. The World Health Organization classifies QoL into several broad areas, including physiological, emotional, and social ones (Huber & Tu-Keefner, 2014). Each of these areas affects all the others while QoL covers the entirety and wholeness. The WHO definition highlights life’s goals, expectations, aims, and anxieties of individuals as they go on and meet life’s sufferings. Health-related quality of life (HRQL) encompasses the person’s entire well-being. According to international experts, HRQL includes the physical, social, and emotional areas of a person’s functions, including awareness of a person’s quality of life and general life satisfaction (Huber & Tu-Keefner, 2014).

Positive and negative effects can be seen on women who undergo a hysterectomy. With the loss of fertility, the woman may become anxious and afraid of the many personal issues surrounding her life and her relationships with the people around her, particularly her husband (Huber & Tu-Keefner, 2014). Women complained of difficulties in uterine problems, including physical and menstrual pain, emotional and sexual dysfunctions, and a decline in general health.

Summary and Conclusion