Introduction

The importance of good governance determines the vitality of corporate culture and allows for improved operational effectiveness by finding constructive solutions to the ambiguous issues that arise in the leadership process. The fundamental figures of corporate governance are the board of directors, each member of which has an interest in the corporate welfare of the company. The plurality of views of stakeholders on the board, however, creates disagreements among executives, each of whom is trying to maximize performance. The reasons for these disagreements can be differential governance and leadership policies, different views of the benefits to the company, and an interest in growing specific performance over others. In turn, unconstructive dispute resolution leads to destructive consequences, realized through conflicts at the highest managerial level of the organization. Failure to agree creates an imbalance of power within the company and wastes corporate resources in seeking self-centered solutions instead of coming to a shared understanding of the organization’s future development. Since all public companies are required to have their own board of directors, traditionally represented by shareholders and business owners, the importance of finding alternative methods of resolution in order to preserve the competitive viability of the company and corporate resources is a hot topic of academic and public debate. This paper examines the phenomenon of conflict within the board of directors as a corporate problem in light of the search for alternative dispute resolution. The work may be of academic interest to corporate governance stakeholders and students because it is based on scholarly research and psychometric concepts of governance.

This paper is designed to address the following research questions:

- Identify the causes of conflict and disagreement among board members.

- What opportunities for conflict resolution exist within the practice of alternative dispute resolution?

- The need for alternative dispute resolution practices in the context of corporate governance optimization.

Background Information

In an era of increasing globalization, more companies tend to go public. Public companies are defined as organizations that make their shares freely available on stock exchanges; anyone can purchase securities in this way. In addition to making assets freely available, public companies are also required to have a functioning board of directors, an executive governing body comprised of several interested parties; however, this practice also applies to non-public, non-profit organizations. The board of directors usually consists of the CEO and senior managers on the company side, as well as individuals who are not directly affiliated with the organization but are shareholders. As a rule, board members do not determine the most important board member, as each of them has equal rights and votes in decision-making. Thus, independent directors are only related to the company through membership on the board but do not make internal corporate decisions outside of the area of responsibility of such a board. There is a requirement that the board of directors be dominated by independent members and outside audit members, but this requirement is not mandatory for multinational companies. The idea behind this preponderance is that the independent members are less biased toward the company’s CEO, which contributes to more realistic business development in the industry marketplace. Outside directors tend to be prominent entrepreneurs or well-known figures whose presence on a collegial body is intended to provide valuable advice on corporate development.

For example, at WW, a company that offers weight loss and self-care programs to clients, board members include Oprah Winfrey. The appointment of new board members is usually implemented through the voting of current members; hence often, the board of directors is expanded by the decisions of current members. Among others, a company’s shareholders may appoint their representatives or members of the company itself as a proxy, which creates opportunities for multiple representations within the board. Thus, a company’s board of directors is represented by insiders and outsiders whose focus is on the corporate development of the company.

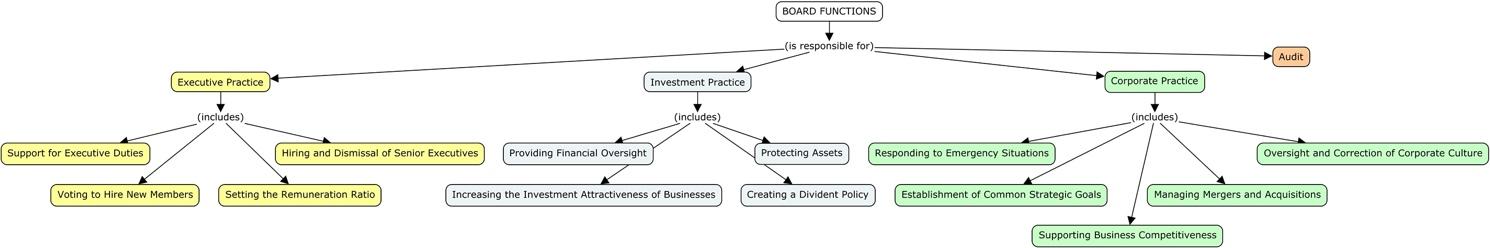

An effective board of directors is a guarantee of the company’s long-term development. Specific board responsibilities include managing and overseeing corporate decisions. Members’ agendas are not lower management issues since line managers are responsible for such decisions. Instead, the board of directors is designed to address broader corporate development perspectives, as shown in Figure 1. In particular, the collegial executive body is responsible for formulating strategies for the development of the public company and organizing the effective management of the lower executives. In addition, the board of directors is responsible for protecting shareholder rights in corporate governance and is responsible for making the organization more attractive to investors. Decisions are made by the board on a regular basis, based on the members’ meeting plan; thus, this body is not permanent but meets according to the plan or decisions requiring extraordinary interventions.

It should also be clarified that the board of directors includes a corporate secretary, who is actually one of the most important resources during the meeting. The duties of the corporate secretary are based on a synthesis of administrative and executive duties, namely providing board members with the resources and capacity to perform fiduciary duties, recording the actions of board members for further archiving, and ensuring communication between directors with the further transmission of decisions to lower levels of the board. In fact, the corporate secretary is the liaison responsible for the technical and administrative ability to conduct regular and extraordinary meetings — without this role, the functioning of the board of directors would be questionable because there would be no administrative oversight.

Conflicts on the Board of Directors

The collegial nature of the board of directors is inextricably linked to extensive discussion and debate regarding decisions made. The boardroom is an open forum in which board members exchange opinions and ideas about corporate governance practices. Given the diversity of professional orientations, cultural and ethnic backgrounds, and perspectives on governance, controversy is a constant practice in any meeting. Effective resolution of such disputes is the key to the commercial development of the company and consideration of the interests of the maximum number of stakeholders. It is for this reason that there are special corporate requirements and guidelines for resolving disputes that help minimize the number of disruptive outcomes. In particular, the corporate practice of companies implies signing a conflict-of-interest policy by a new member of the board of directors, which prevents unfair actions of a participant aimed at multiplying personal benefits from management contrary to long-term benefits for the company. As an example, corporate practice at Apple, Inc. has guidelines for emerging conflicts between directors and the corporation — Apple requires each director to report and document existing conflicts to the corporate secretary, which allows for meaningful resolution of conflicts between interested parties. Such a strategy creates a common understanding of the main purpose of executive management and prevents the development of shady schemes.

In practice, the multiple disputes that arise in the boardroom actually tend to escalate into conflicts. Conflicts can be dangerous because by definition, “the conflict is a disagreement within oneself or differences or dispute among persons that has potential to cause harm“. In other words, unlike business disputes, conflicts are a threat to operational efficiency, and the lack of solutions is destructive to the companyhave. It should be clarified that while disputes are a frequent practice for corporate meetings, conflicts turn out to be much less frequent due to their destructive nature. In particular, conflicts of interest at the managerial level are associated with emotional tension among participants, resulting in impulsive and biased decisions. In other words, executive conflicts distort decision-making processes and undermine trust among board members. At the same time, discord at the highest level of the board has a destructive effect on the hierarchy of authority within the company, as disagreements and disagreements between directors are extrapolated to lower departments. For example, if there is a conflict of interest between a technical director and a program director within a large technology company, there is an increased likelihood that their instructions to senior managers will differ, resulting in corporate disagreements and higher operating costs. Thus, board conflict illustrates a crisis state of governance, which in turn demonstrates the quality of corporate culture.

Causes of Corporate Conflict

Since the destructive effects on the company are already known, it is appropriate to examine the predictors of such conflicts. Individual corporate dynamics, dependence on geography and professional direction, and the personalities of board members create a plurality of causes of corporate conflicts. Cossin and Hongze Lu distinguish several levels of conflicts depending on the nature of their origin. The first level is based on actual disagreements between a board member and corporate interests. The main reason for such disagreements is the personal policy and management vision of a particular board member who, in management practice, has decided to distance himself from the unified corporate board. This estrangement is particularly intensified in circumstances where a director finds himself or herself involved on several boards of different companies in order to receive large compensatory rewards. Directors are forbidden to pursue self-interest purely in governance because it is contrary to the practice of a collegial board of directors. Examples of such bases for disagreement include misappropriation of company assets, self-dealing, and neglect of fiduciary duties.

The second level for conflict to develop is the condition in which some board members find themselves dependent on the decisions of other members. In an ideal environment, each member should be independent of the opinions and ideas of others, bringing diversity and a personal perspective to corporate practice. In practice, however, it happens that some board members exert a dominant influence over others through bribes, favors, or psychological manipulation. In this case, the board is as biased and dysfunctional as possible because the diversity and inclusion initially invested in the board’s philosophy are inhibited. As a consequence, an explicit or implicit concentration of interests is formed on the board that opposes the rest of the participants: in the event that a vote is required, the dominant participant has an advantage of votes, thus creating a biased bias in decision-making.

Resolving Conflicts on the Board of Directors

When conflicts arise between board members in an organization, the corporate secretary is required to document all actions so that the conflict becomes substantive in nature and is not purely subjective. Conflict prevention often also comes from the corporate secretary, whose practice often includes regular questioning of board members to ascertain critical concerns and problems they face in the performance of their fiduciary duties. However, if a conflict does occur and operational effectiveness is hurt, it is the board’s job to find the quickest possible solution to the problem that has arisen. In turn, such solutions should be divided into two categories, namely, direct (judicial) resolution, and alternative options.

With regard to the direct settlement of a conflict situation, it should be noted that the inability to come to a shared understanding and find a compromise leads to the need for legal action. One of the most common practices of litigating conflicts is the direct or indirect actions of board members that led to a significant drop in the company’s stock. For example, in 2015, Paiman Rahimi, a shareholder in coal mining company SouthGobi Resources (SGR), sued the board of directors because of their deliberate misrepresentation of financial information, which led to poor decisions and served as the basis for a decline in the company’s stock price.

The problem was the deliberate disregard of a rule to change the company’s financial policy regarding the recognition of revenue from coal sales: until 2012, the company considered customer prepayments as revenue, which it recorded under IFRS, but starting in 2012, the company switched to a new financial regime in which customers were first provided a product and then a profit was recorded. SGR’s corporate directors failed to record changes to the financial statements, and when the situation became public, the company’s share price fell by 18%, affecting key investor Paiman Rahimi, who formed a class action lawsuit on behalf of all shareholders. In Rahimi v SouthGobi Resources Ltd, 2015 ONSC 5948, a Rahimi shareholder sued the individual board members responsible for publishing the financial statements, and the Ontario Court of Appeal will uphold his claim.

Nevertheless, not only a shareholder but also any client who suffers from decisions made by the directors can file a lawsuit against the board of directors. For example, in Matlock v. Ottawa-Carleton Standard Condominium Corporation, 2021 ONSC 390, Canadian citizen Michael Matlock sued certain members of the board of directors of Ottawa-Carleton Standard Condominium Corporation in bad faith in their fiduciary duties. The problem was that the decisions made by the directors led to technical and aesthetic violations in the condominiums purchased by the citizen. The Ontario Superior Court of Justice could not grant Matlock’s claim against the board of directors, but this case was revealing because it demonstrated the real possibility of legal interaction between the client and the company’s highest collegiate executive body. However, lawsuits against the board of directors, whether by clients or on behalf of individual board members, require significant resources of time and money, which increases operating costs and inhibits effective business development. As a consequence, there is a need to turn to alternative dispute resolution options to cover the identified disadvantages of litigation and increase operational efficiency.

The Problem of Finding an Alternative Solution

By now, conflict psychology has managed to accumulate sufficient evidence, which allows applying alternative ways of solving disputes and conflicts between individuals, including in the corporate practice of executive management. The basis for finding alternative solutions is always a constructive dialogue, which allows, first of all, to understand the essence of the crisis situation. Thus, any conflict, including domestic conflict, is built on the problem of different interests of stakeholders arising from the relationship. As has already been shown, such relationships within the board of directors are businesslike but do not prevent the emergence of controversy. Conflict consumes many emotional and cognitive resources of the disputing parties and creates professional tension, leading to the destruction of the executive performance of the governing body. By now, it is essential to emphasize that the form of conflict between board members is not unlike any other domestic conflict, the only difference being that the focus is on solving business issues. Thus, among the standard formulations from board members, one might expect the following phrases:

“I am acting this way because he/she started it first.”

“My interests have been grossly violated.”

“I do not feel my voice is meaningful in making key decisions.”

Whatever the specific wording of the conflict, it is critical for disputants who are interested in finding a constructive solution to come to a shared understanding and maintain the psychological literacy of the dispute. Excessive emotionality results from the violation of personal boundaries and perceived interests, causing the individual to unconsciously trigger psychological defense reactions: fear, screaming, or domination. Personal or overly expressive behavior by board members is destructive to the resolution of a dispute, so the key challenge is to find mitigating factors to inhibit the overly emotional nature of the conflict. For example, Harvard Business Review (HBR) suggests several strategies for moderating such behavior in order to calm down and resolve conflict intelligently. HBR includes:

- Breathing exercises to practice mindfulness and calmness;

- Focusing on parts of one’s body to practice mindfulness and concentration;

- Saying a mantra to allow for relaxation;

- Acknowledging one’s own feelings and believing that it is normal to experience them;

- A break in the discussion to have free time to calm down

The practices described above are just a few examples of mindfulness that allow one to initially tone down the emotional tone of the conflict and create a foundation for a constructive solution. Each individual’s uniqueness allows him or her to choose their own techniques perceived as working. Once emotionality and resentment have been let go, directors can begin looking for alternative solutions to the dispute. The following sections discuss specific alternative dispute resolution practices in detail.

Negotiation

Negotiation is an essential function of alternative dispute resolution because it seeks constructive answers. The essence of negotiation processes comes down to adequately considering the interests of each of the conflicting parties, covering their needs, and seeking multilateral satisfaction from the results. Addressing the definition allows us to consider negotiation as “any form of direct or indirect communication whereby parties who have opposing interests discuss the form of any joint action which they might take to manage and ultimately resolve the dispute between them”. The difference with the direct method of conflict resolution is noticeable: unlike litigation, negotiation is aimed at achieving the well-being of each of the numbers involved. Obviously, effective negotiation by the parties requires an understanding of personal interests. Specifically, in the HEXIGLASS role play, my interest as a plant manager was to retain the current workforce because the corporation is responsible for such valuable talent and cannot neglect them in an effort to improve the operational efficiency of the business.

On the contrary, the other manager’s interest was to fire excess employees in anticipation of immediate profits, which seemed questionable to me. In this case, the conflict between us was not resolved through litigation, but rather, we went into negotiations in which the interests of both sides were taken into account. For example, if in a corporation, the CFO opposes increasing the CEO’s compensation because of a difficult economic period for the company, the conflict of interest, in this case, is based on the directors’ business needs: the CEO is interested in increasing his own compensation to increase motivation, while the CFO is interested in the economic well-being of the company. Understanding of the interests emerges at the moment when the excessive emotionality of the conflict has been inhibited, and free space has been created to think about the personal interest in the conflict and to establish boundary conditions. Thus, the negotiation process for conflict resolution is an area for corporate value creation, which is why it is critical to design negotiation practices carefully.

Negotiations can be carried out personally by those involved in the conflict if they are willing to come to a common understanding. In the above example, the CEO and CFO could work out their own problem through negotiation. In this case, it is critical to find a compromise that satisfies the parties involved and achieves the desired outcome: for example, a commitment to increase compensation as the company achieves a specific economic metric as a reward for demonstrated performance. An essential issue in the decision to negotiate is the perceived value of winning or losing. In the case of the board of directors, for example, improving corporate practices is not a tangible benefit, making it difficult to understand the need for a negotiation process. Instead, directors must be able to feel value in this way of resolving conflict in order to feel motivated to continue negotiating.

On the other hand, negotiation can be accomplished through a mediator if board members do not have the motivation or free time to resolve specific disagreements. As Farrow points out, “more publicly, representatives are engaged to assist with the creation or transition of relationships and the resolution of disputes in almost all sectors of society involving almost all types of issues: commercial transactions, investment decisions, real estate deals, labour disputes, plea bargaining in criminal law, family disputes, immigration issues, education issues, etc.“. In the case of a board of directors, mediators can be represented either by appointed figures specialized in conflict resolution — conflict resolution agents, attorneys, official representatives — or by the corporate secretary of the organization. Generally speaking, all representatives can be called ombudspersons, responsible for controlling and enforcing the interests of the customer (board member) in the negotiation process. In fact, the involvement of intermediary agents complicates the negotiation process, as it creates a forced need for additional communication. Nevertheless, this strategy is necessary if the conflicting parties themselves cannot come to a joint peaceful agreement that satisfies the interests of both sides. In addition, the use of mediators has the added advantage of buying time and learning more helpful information for the conclusion of an agreement. For example, if one of the conflicting parties requests specific terms for a deal, the mediating agent can state that he has no authority to make such decisions, thereby buying time for the second conflicting director to think through the terms.

While negotiation is an excellent and most flexible tactic for alternative conflict resolution, its implementation requires serious preparation. In the boardroom business environment, negotiation may be perceived as the only way to effectively reach an agreement between conflicting parties, which is why negotiation practices often fail. For example, Kolb and Williams reported that direct negotiations are often accompanied by shady negotiations in which the conflicting parties seek to challenge the legitimacy of the opponent and achieve personal reputational gains. In addition, negotiations can fail if there is a need to rush; the parties may worry about the lack of time, which leads to a violation of the philosophy of the negotiation process. Lack of coordination is also a problem, especially during mediation negotiations. The corporate secretary, in this case, is responsible for providing sufficient conditions for the negotiation process: scheduling separate meetings, inviting outside representatives, and comprehensively documenting the interests of each party.

Thus, for the negotiation process to be successful and for each of the conflicting board members to come to an amicable agreement, negotiations must satisfy several conditions. First, negotiation must be based on a mutual desire to solve the problem out of court in order to save critical operational resources and come to a joint agreement more quickly. Second, the negotiation process must be entirely voluntary; no one can force the conflicting party to negotiate because, ultimately, the philosophy of negotiation as a process of finding a satisfactory solution for all will be violated. Third, negotiations do not have to be formal — when both parties are seeking to reach an agreement, they can use whatever rules and language seem appropriate to them. The corporate secretary is still required to document the negotiation process, but this obligation has no effect on the dynamics of the negotiation. Fourth, the negotiating parties may come to a joint agreement on secondary issues before seeking a resolution of the primary source of conflict. The CFO (or his representative) may request the CFO (or his representative) to keep the negotiation process confidential in order to preserve his reputation, in which case the negotiation process documented by the secretary may be destroyed by the joint agreement of both parties and marked as confidential. As part of maintaining confidentiality, it is critical that the parties’ agreement does not violate the corporate values of the business, as the negotiation increases the likelihood of creating a micro group of interested board members who would end up having a common strategy that is contrary to the interests of the corporation. Fifth, negotiations can also be public if both parties agree: in the case of public negotiations, outside observers, whether board members, the corporate secretary, or an auditor, are invited to join the process, whose responsibilities are defined by a witness role. Sixth, every conflict must eventually come to a peace agreement that satisfies the interests of the parties and thoroughly resolves the crisis situation. It is reported that a peace agreement in a business environment must be documented in writing and have the hallmarks of stability and durability. This seems appropriate since the actual point of a peace agreement is to reconcile the warring parties, and thus this outcome must be final, not implying any reticence or contradiction in the interests of board members.

The Department of Justice Canada identifies several styles of negotiation, depending on the positions taken by the conflicting parties. The first style was called positional negotiation, the logic of which is reduced to the desire to multiply their benefits as a result of the negotiation process; in this case, the initial philosophy of the negotiation process is violated, despite the formal adherence to the general rules. The criticism of this style of conflict resolution is transparent: in positional negotiations, one party takes an adversarial position in relation to the other, which creates an impossibility to come to trustful communication and, consequently, prevents the achievement of organizational success. The second style is what the Department of Justice Canada calls collaborative negotiation, the meaning of which is diametrically opposed to the positional approach. In collaborative negotiation, the conflicting parties proceed on the assumption that one party’s gain does not come at the expense of the other party’s loss. In these negotiations, an amicable agreement is reached by respecting the common interests and taking into account the needs of all concerned parties: as a result, the result is satisfactory for each of the opponents. It is clear that if a prosperous corporate environment is achieved, a collaborative approach to negotiation is integral to the practice of dispute resolution among board members because the outcome has benefits for all parties involved, both in the short and long term.

Finally, a third, youngest style of negotiation, referred to by the Department of Justice Canada as principled bargaining, is postulated. In fact, principled bargaining is a compromise between positional and collaborative approaches to conflict management. In this case, it is not so much the interests of particular parties to the conflict that prevail, but rather some common just values that determine the outcome of the negotiations. Fisher and Ury refer to this method of negotiation as “hard on the merits, soft on the people“, postulating the objective unambiguity of this method of dispute resolution. A particular advantage of this approach is the universality of its practical application, which means that principled bargaining can be appropriate for both hard and soft in terms of communication by board members.

Mediation Role

As globalization processes intensify, so does the role of the negotiator, who becomes an essential link in mediation between conflicting parties. MacFarlane describes in his book the phenomenon of the new lawyer, who is rapidly moving away from the image of a conflict-only professional to one focused on conflict resolution: “the New Lawyer … must find creative, practical, and affordable ways to meet his or her clients’ expectations… this means a shorter time frame for achieving effective, appropriate, and sustangible outcomes… means greater transparency about likely outcomes – and more frank talk about what can and cannot be achieved in the current justice system“. In other words, the expansion of the mediator’s functions has a significant impact on the progress of the conflict and is designed to resolve the dispute professionally in the shortest possible time, without bringing it to court.

As noted above, the role of the mediator in the negotiation process is essential when the conflicting parties lack the motivation or free time to solve the problem on their own. Lack of motivation, often accompanied by personal grievances against the opponent and, as a result, excessive emotionality, can be beneficial to the negotiation process, as the mediating agent is meant to respect the conflict and address the issues that arise in a professional context. In reality, the use of a mediator in the form of legal counsel, a personal agent, or independent parties has an ambiguous impact on optimizing conflict resolution, including increasing the time for communication between the parties. Inviting a professional negotiator with competencies in solving business conflicts allows for a more substantive approach to the dispute and a firmer assertion of one’s own views, which is especially relevant in situations where a board member finds himself under dominant pressure from his peers. This strategy, among others, was clearly demonstrated in the role play inviting Lafredo Associates to participate in the conflict as a mediator. An essential feature of mediation to ensure the negotiation process is the absence of discrepancies between the position of the negotiating agent and the conflicting party — the legal adviser must fully represent the interests of his client and ignore personal wishes and needs unless the situation is directly detrimental to the agent. Inhibiting potential discrepancies is the responsibility of the mediator, whose job is to clarify all the details of the conflict in advance in case the agent encounters unforeseen claims. Among others, it should be clarified that a board member may be present during the negotiation process but not actually participate directly, giving the floor only to his representative: this solution achieves a more active involvement of the board member in the negotiation process since personal communication takes place between the clients and his representative.

In practice, the number of conflicts between constantly evolving corporations, especially in a diverse and inclusive environment that encourages a plurality of conflicting views in the boardroom, is constantly increasing. While turning to independent legal counsel can be a sound practice that brings a fresh perspective and persuasive techniques to the corporate environment, this method is associated with risks. In particular, the independent mediator must be well informed, which wastes the valuable time of board members and reduces operational efficiency. This is why MacFarlane reports the emergence of the role of corporate counsel, someone who works directly for a given company and has all the necessary information to resolve conflicts. In-house counsel saves the corporation valuable time and provides professional alternative dispute resolution services more efficiently with their available resources.

Practical Application of Alternative Dispute Resolution

Since conflict has become understood as a phenomenon and the need for its professional resolution is no longer in doubt, there is a need to discuss several academic practices that allow for the application of what has been learned to corporate board practices. The recommendations and strategies described below fully justify the ultimate goal of this study, namely, to increase awareness of a culture of alternative dispute resolution in the business environment. The conflict has previously been closely associated with the excessive emotionality of feuding parties, so it seems logical to assume that emotions should be ignored in dispute resolution. In fact, ignoring emotions leads to severe psychological affects and is destructive to the mental well-being of the individual — in turn, the destruction can be extrapolated to the course of conflict resolution, from which no one benefits in the long run. It is critically important to be able to manage emotions, to understand and anticipate them, but not suppress them. Successful resolution of a business conflict also requires listening to one’s opponent and understanding his or her concerns and opinions about the subject matter of the dispute — the absence of this understanding does not lead to a constructive solution, as ultimately reaching an amicable agreement in which the interests of each party are satisfied is inhibited. Moreover, in a conflict, there is no need to sort out who is right and who is wrong, for this is not the focus of competent dispute management. On the contrary, an effective solution must be directed toward a compromise outcome, not the clarification of personal grievances.

When entering the negotiation process, each side must be convinced that it feels safe to share its experiences and seek a common solution together. Board members are holders of valuable trade secrets, so the negotiation process may reveal sensitive aspects that directors do not want to make public. In addition, security concerns relate to the desire to be heard because if the opponent is not yet ready to do so, negotiations will fail in terms of reaching a universal agreement. It should be made clear that the negotiation process as an alternative way of resolving the dispute cannot be initiated until each side comes to the understanding that the opponent is ready to negotiate and really wants to work to resolve the crisis situation. Stone, Patton, and Heen also describe the importance of language that negotiators can utter to encourage constructive development of the solution work. In particular, such language should include the construct “Yes, and…” — the semantic meaning of these words is to initially agree with the position of one’s opponent with the further addition of one’s own facts. This is radically different from the formulation “No, but…” because, in this case, the board member shows that he is not inclined to agree with his opponent’s opinion and is ready to hear only his own arguments. Verbal constructions beginning with the pronoun “I” rather than “You” are also necessary: in the latter case, the opponent cognitively reads the claim into his side, whereas the phrases “I…” help to broadcast his own interests and concerns and to delegate responsibility for the conflict. Another valuable lesson from the authors is to focus on each side’s contribution rather than blaming. This partially correlates with the previous recommendation to use specific language but extends it. In more detail, the board member should recognize that his or her opponent has made an essential contribution to the discussion and has offered an alternative opinion, even if it seems wrong to the director.

To effectively resolve a business conflict, board members must do preparatory work that allows them to recognize their own concerns about the issue at hand and gather the necessary information. Starting a negotiation without preparation can be futile, as the parties may not have sufficient knowledge and resources on the topic of the conflict. This is especially true when a new board member has been added to the board with whom there is already a conflict of interest during the first meeting. In this case, it is helpful to learn more about the other side of the negotiation process beforehand in order to modify your own negotiation strategies. If, on the other hand, negotiations reach an impasse and there is a lack of information, it is okay to take a break to develop new strategies or discuss further development of the solution work with legal counsel. Taking the initiative over the solution can also be helpful, as it assures the board member that his or her interests will be taken into account; however, it is essential to ensure that taking the initiative does not inhibit the opponent’s involvement.

Bibliography

Books

Colleen Hanycz et al, The Theory and Practice of Representative Negotiation (Toronto: Emond Montgomery, 2008).

Deborah M. Kolb & Judith Williams, Everyday Negotiation: Navigating the Hidden Agendas in Bargaining (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003).

Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen, Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most (New York: Viking Penguin, 1999).

Julie MacFarlane, The New Lawyer: How Settlement Is Transforming the Practice of Law (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008).

Linda M. Ippolito, Music, Leadership and Conflict: The Art of Ensemble Negotiation and Problem-Solving (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

Roger Fisher & William Ury, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In (London: Penguin Books, 2011).

Roger Fisher and Daniel Shapiro, Beyond Reason: Using Emotions as You Negotiate (London: Penguin Books, 2005).

Journal Articles

Chen Wang, Ye Qing, & Goyal Abhinav, “Does Tenure Matter: Role of the Corporate Secretary in Chinese-Listed Firms” (2019) 33.1 JAH 181.

Rano M. Piryani & Suneel Piryani, “Conflict Management in Healthcare.” (2019) 16.41 JNHRC 481.

Raul Beal Partyka et al, “Family Businesses and Independent Board of Directors: Strategies for Company’s Longevity” (2021) 13:1 GBMR 1.

Law Cases

Tammy Nestoruk, WeirFoulds, 2017. Web.

Linda Fuerst, NRF, 2017. Web.

J. Beaudoin, CanLII, 2021. Web.

Online Materials

Apple, Inc., Guidelines Regarding Director Conflicts of Interest, 2008. Web.

Beth Doherty and Hal Movius, Program on Negotiation, n.d.. Web.

SEC, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 2003. Web.

Amy Gallo, HBR, 2017. Web.

DJC, Department of Justice, Canada, 2018. Web.

Didier Cossin & Abraham Hongze Lu, IMD, 2021. Web.

James Chen, Investopedia, 2022. Web.

WW, Board of Directors, 2022. Web.