Introduction

Emergency behavior and social identity aspects are not connected at the first sight. However, if a person appears in a critical situation, the flocking instinct rules the entire mass. This is explained by the complex reasons of social behavior, emergency behavior patterns, survival instinct, and social identity of the persons who appeared in a critical or any other emergency.

This report aims to analyze the live research of human behavior in a life-threatening situation when the space is restricted, and the realization of the approaching danger is too evident. The paper will involve the results of the research, as well as assessment of these results in accordance with the social behavior theories and concepts, and the key background of the research is the individual and collective identity of the people. Therefore, it was presupposed that collective identity makes people help each other more frequently, and push each other less frequently.

Theoretic Basis

Mass psychology in disasters is represented in numerous researches, and most authors come to the conclusion that behavioral patterns that people use in emergency situations are mainly dangerous as for themselves, as for the surrounding people. The given situation involves the opportunity of a fire in a restricted area (subway) and great amassment of people who wish to save their lives. In general, people’s behavior is subjected to particular rules and principles, and a clear understanding of these rules may be helpful for a clear forecast of the possible consequences in a critical situation. Additionally, as it is stated by Drury and Cocking (2007), injuries may be caused not only by the disaster itself but by the human factor as well. This factor involves the procedures and services aimed at rescuing people or mitigating the consequences of a disaster, but also by the behavior of a panicking crowd that is attempting to be evacuated. Panic, disorganization, irrationality, and negative emotional egress are the additional factors that rule people and may cause even more harm than the emergency itself. On the other hand, the human factor also involves a factor of a leader, interpretation of the events, decision-making, and social influence. These may define the entire outcome of the situation, as well as the success of the rescuing operations.

Kugihara (2001) conducted a special research associated with the crowd aggression, and effectiveness of the rescue process. It has been found that aggressive behaviour of the group was featured with the increased time of a jam, while low aggression helped to cope with a jam more effectively. Therefore, it is emphasized that the actual importance of clear understanding of human behaviour is quite helpful for controlling the critical situations, while the patterns of human behavior are closely linked with the values of social psychology concepts, and theoretic approaches. Hence, in accordance with the research by Kugihara (2001, p. 589):

The results of the sequential analysis suggest that when individuals have the option of aggressive behaviour, they seem more ready to react aggressively against the aggression of others than the case in the smaller groups. It seems likely that in larger groups, it may be more difficult to identify others individually, making it more difficult to understand their intentions and coordinate responses. Many groups fell into such a negative spiral of aggression stimulating more aggression.

In the light of this fact, it should be emphasized that the human behaviour patterns and social identity principles are quite evident, and are not hard to forecast. Human behaviour in extreme situations is mainly selfish, and those who need help may not be heard because of this selfishness, aggression, panic, and disorganization. Moreover, Kugihara (2001) emphasizes that people may not remember, or be ashamed of their aggression, and other behavioural patterns, which means that loss of the control with the following giving way to flocking instinct is a common feature of acting in a panicking crowd.

Description of the Experiment

The experiment was modelled using virtual reality technology that is generally needed for performing researches that can not be performed in a real world because of numerous factors and reasons. Therefore, the situation involved behaviour of people in a restricted surrounding of a subway. Emergency was represented with a dense smoke, and the evidence of fire, hence, the entire crowd had to be evacuated as soon as possible. Such factors as rationality, mutual assistance, aggression, and effectiveness of the evacuation were assessed.

The experiment was divided into two parts: the first included human behaviour with collective identity, while the other – with individual. The scenarios of both experiments are as follows:

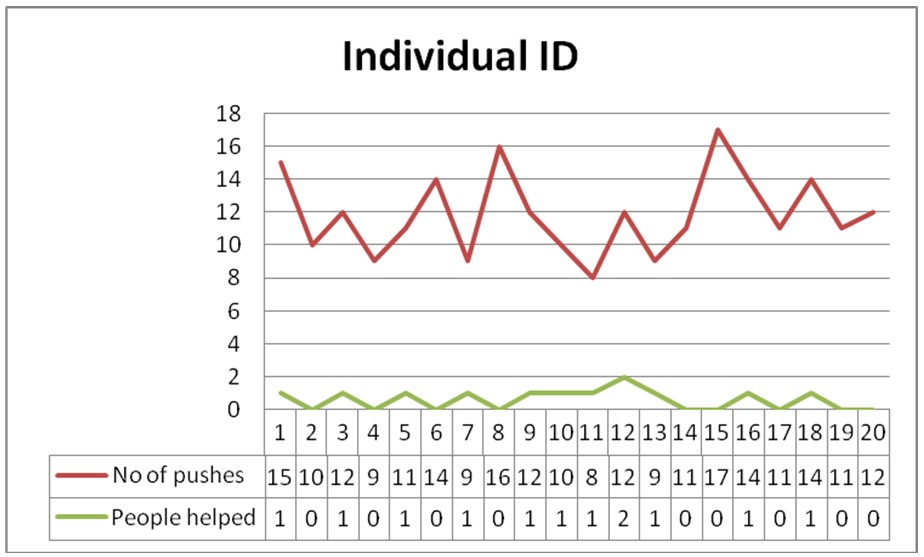

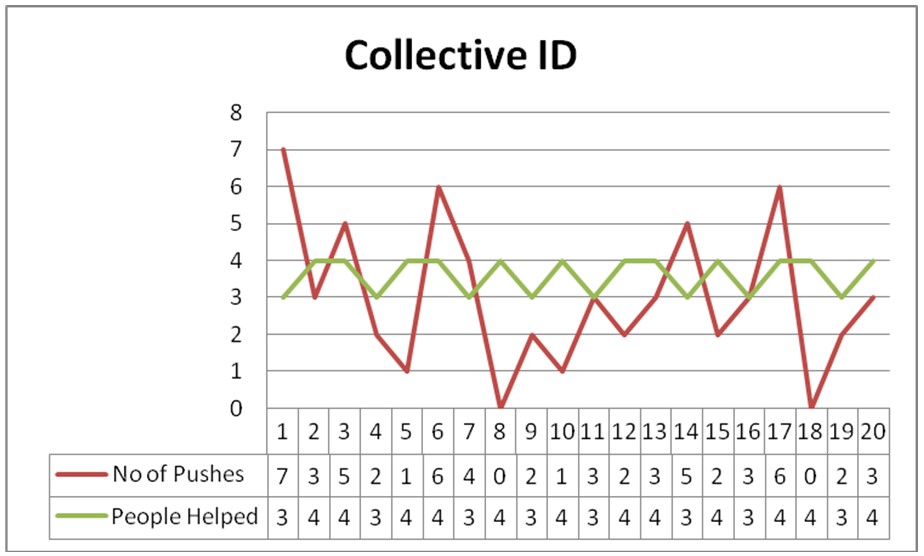

The results of the experiment are given on the figure 1 and 2 of the Appendix. In the light of the data given on the graphs, it should be stated that the aggression level is generally identified by the identity pattern of each individual. Hence, applying it to the research by Kugihara (2001), it should be emphasized that aggressive behaviour is featured with individual identity, while collective identity presupposes the increased level of sympathy, responsiveness, and care of each other.

Analysis

In accordance with the results of the research, the analysis and conclusions that may be achieved are closely linked with the values of the social identity that are researched in this experiment. Therefore, it is stated that if people in an emergency situation are controlled by their social identity behavioural patterns, they are more responsive, sympathetic to each other, and less aggressive, and vice versa if the identity pattern in individual. Considering the research by Drury and Cocking (2007, p. 10), the following statement should be emphasized:

The affiliation and normative approaches explain the sociality of the crowd as deriving from pre-existing relationships: either from the existing social structure (which provides the norms and roles that people maintain) or from interaction in the small group and interpersonal ties (which shape their patterns of affiliation). However, while there is indeed evidence of normative structure and affiliation in emergencies, there is also evidence of behaviours in crowds that does not seem to be adequately explained by these kinds of processes.

In the light of this statement, it should be emphasized that social identity behaviour patterns are defined by the rules and norms that are generally accepted within the society. Hence, if these norms are high, the human behaviour will be corresponding, while low norms turn social identity into a flocking instinct, and humans are turned into panicking animals.

Hypothesis Test

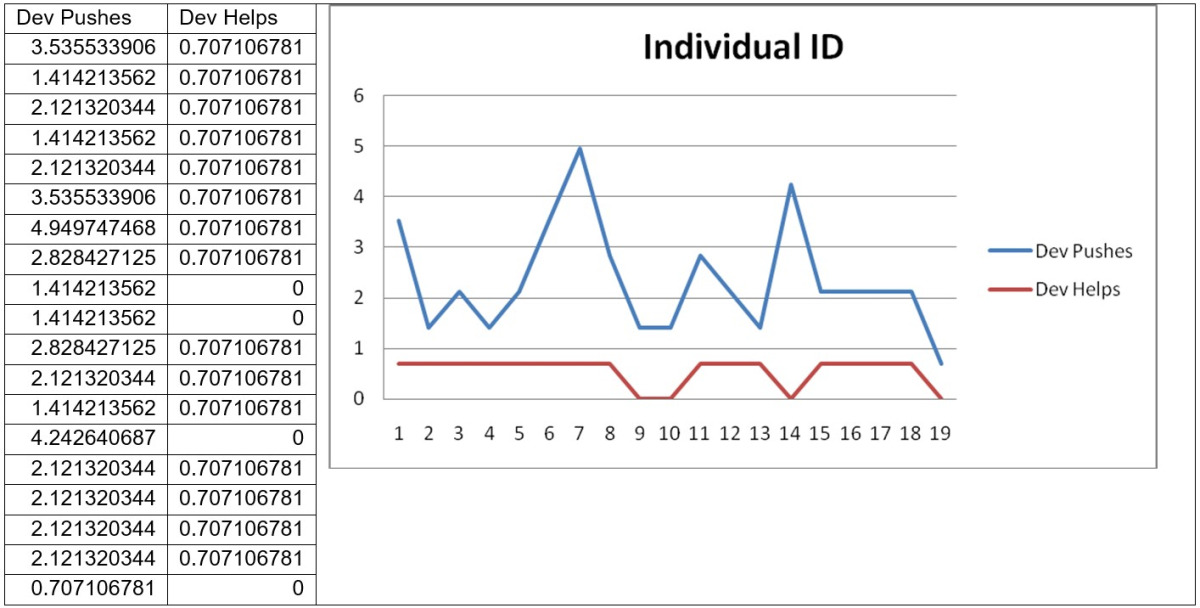

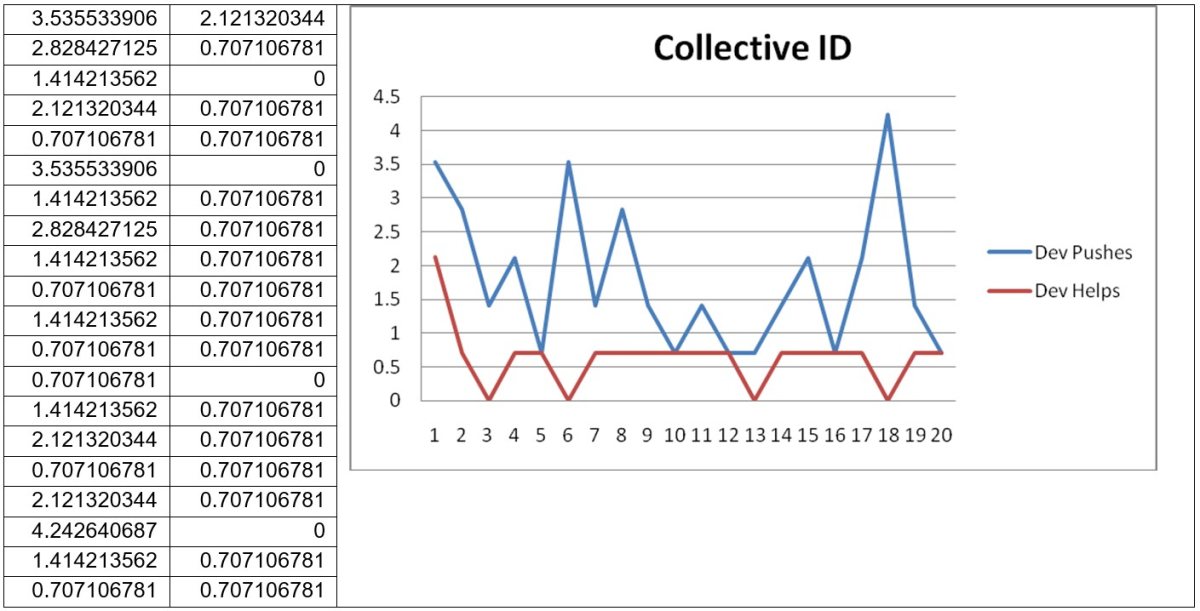

Test data are offered on figures 3 and 4 of the Appendix. In accordance with the data provided, it should be emphasized that the actual hypothesis of the test is confirmed. Statistical data given in the tables of figures 3 and 4 emphasize that collective ID for people is more favourable, as number of helps is higher, while the deviation level is comparatively the same in comparison with the deviation of an individual ID. The number of pushes is featured with lower deviation in collective ID test, which means that people are not subjected to their mainly selfish behavioural patterns, and try to adjust their behavioural patterns for the generally accepted norms of the society. Additionally, it should be emphasized that the actual importance of the hypothesis confirmation is closely associated with the values of social psychology concepts given by Kugihara (2001). Therefore, the deviation values confirm the hypothesis, and regardless of the additional conditions that may be given for the test, the general image of the human behaviour will be the same.

Considering the fact that any stimulus regulated human behaviour in this test (neither positive nor negative), and the participants were told to treat the test like a real situation, the results of the test are subjected to sufficient distortion. This maiy be explained by the fact that actions on the screen can not be treated seriously, and at least 20% of the button pushes (whether “P” or “H” button) were caused by curiosity. In the light of this statement, it should be stated that behaviour of the people would differ in a real situation. Therefore, as it is emphasized by Ruzek et.al (2008, p. 397):

In the immediate aftermath of large-scale events and/or acts of terrorism, many of the survivors understandably experience shock, anguish, anxiety, and various symptoms associated with acute stress. Acute stress reactions involve a range of experiences, including painful re-experiencing of the event, emotion al disengagement, difficulties with short-term memory, concentration, decision-making, insomnia, hyper arousal, and exaggerated startle reactions.

Hence, the situation modelled on the screen lacked these factors, and the results of the test may be treated like a general basis for further researches, and modelling.

Conclusion

Considering the fact that the modelled situation was not featured with some important aspects of a real extreme situation, the importance of the research may not be full. However, it has been confirmed that the differences in social and personal identity behaviour principles differ, as social identity presupposes more frequent help to the others, and less frequent pushes. However, the speed of the evacuation, number of injuries stay the same.

Reference List

Drury, J, and Cocking, C. (2007) The Mass Psychology of Disasters and Emergency Evacuations: A Research Report and Implications for Practice. Department of Psychology, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton.

Kugihara, N. (2001) Effects of Aggressive Behaviour and Group Size on Collective Escape in an Emergency: A Test Between a Social Identity Model and Deindividuation Theory. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 575–598.

Ruzek, J., Walser, R. et.al. (2008) Cognitive-Behavioral Psychology: Implications for Disaster and Terrorism Response. National Center for PTSD VA Palo Alto Health Care System. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine.

Appendix