Introduction

The national health care system is one of the key public policies designed to enhance the quality of life, increase longevity, reduce mortality and morbidity, and address the clinical needs of diverse populations. Many critical government indicators, including the happiness index, quality of life, and life expectancy, depend on the healthcare system’s efficiency, automation, optimization, and productivity. Health Insurance & Health Policy students must be able to critically evaluate existing healthcare systems, identify strengths and limitations, and consider weaknesses that must be improved to achieve the core functions of healthcare structures. This report’s analysis will focus on Canada’s system, one of the most prominent healthcare systems in the world.

Demographic Characteristics

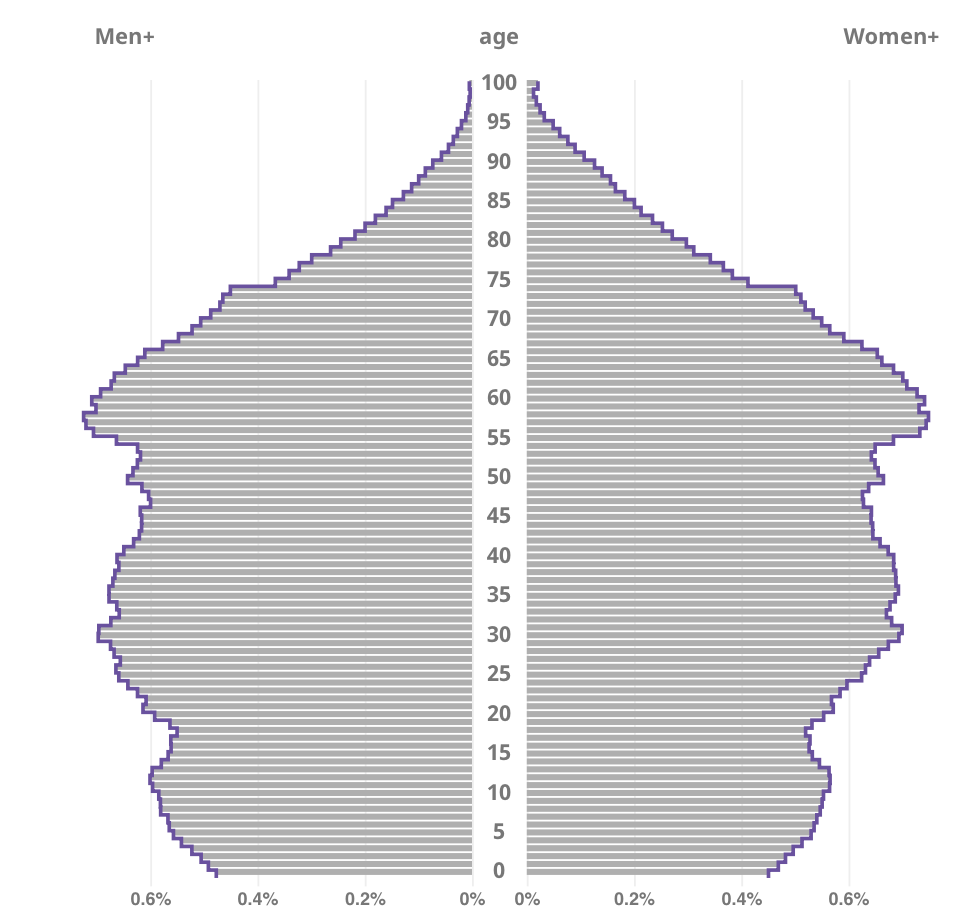

Canada is the largest country on the continent of North America. As of January 1, 2023, it has a population of 39,566,248, an increase of 0.7% over the previous year (SC, 2023). Notably, the average age of Canadians is 41.0 years, down 0.1% from a year earlier. The age pyramid in Figure 1 shows a lower population of older people than younger people. However, the total population under age 14 (15.6%) is lower than for the older generation (18.8%). Combined with the evolving healthcare industry, technological advances, health promotion, and early diagnosis, this fact may indicate an increase in the aging population.

Overall Representations of Canadian Health Care

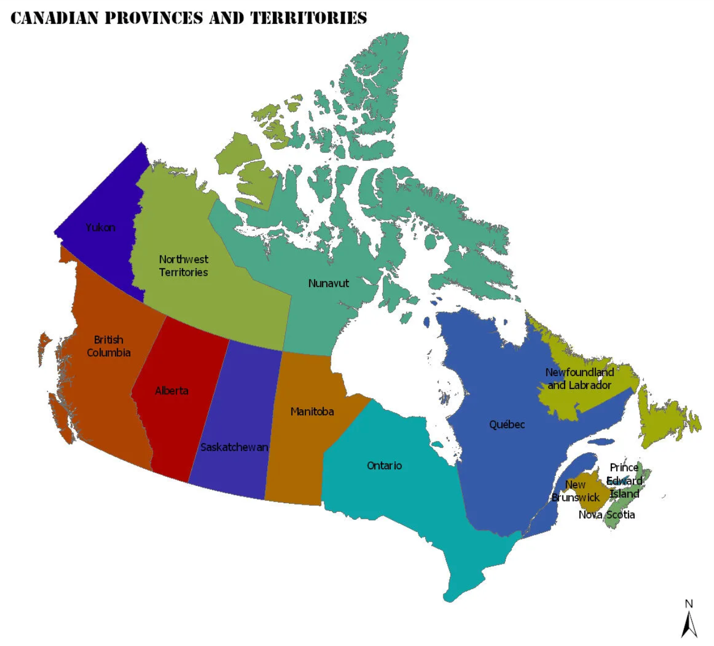

It is paramount to say that in terms of administrative division, Canada is represented by ten provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador) and three territories (Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut), as shown in Figure 2. A key feature of Canadian health care is that it is publicly funded and based on a system of insurance and health plans that offer virtually free clinical care to the public. Government funding, however, does not mean that Canadian health care is under the federal government’s jurisdiction; rather, it is under the control of provincial and local governments but is bound together by the same government-wide principles (Tikkanen et al., 2020). Thus, the local governments of each of Canada’s thirteen political units have healthcare agendas that are fair to the region. This includes funding, management, administration, and forecasting tasks, including budgeting, based on the conditions and circumstances relevant to the region.

Canada’s public health care system is called Medicare, under which every resident must have a Health Insurance (HI) card. Historically, Medicare was established in 1984 when the two existing federal healthcare laws were merged (Tikkanen et al., 2020). It is the responsibility of the federal government of the monarchy to establish Medicare principles binding on each of the 13 provinces or territories. These principles include obligations to prevent disease, promote healthy lifestyles, and provide health care to vulnerable populations, including indigenous people. In addition, the federal government provides partial funding for Medicare, but budgeted health plans, in general, may vary among the regions.

More specifically, the federal government provides five national standards that are mandatory for each of Canada’s administrative divisions. They consist of the principles of public administration, comprehensiveness of coverage, universality, portability, and accessibility (Tikkanen et al., 2020). First, territorial and provincial health care should be publicly administered; that is, government organizations take on the role of legal regulator, and health care services are delivered by various providers.

Second, Medicare provides comprehensive coverage of health services, ensuring that the population has unfettered access to basic clinical services at virtually no cost. Third, the principle of universality postulates that there should be no discrimination concerning clinical access and that all residents should be able to seek care. The fourth principle states that a resident of Canada has the right to see a physician in any province or territory where he or she is, regardless of where he or she is registered, which is especially useful for frequently traveling Canadians. Finally, the federal government has established the principle of affordability, whereby patients do not have to bear the financial burden of covering basic medical expenses and are not charged any user fees.

Another distinguishing feature of Canadian health care is the absence of a public clinical system familiar to many other countries. While some countries have community clinics, where healthcare workers are not-for-profit employees and receive a stable salary set by the government, this is not the case in Canada. In particular, community health workers often have private practices and greater autonomy and can work in multiple clinics (Tikkanen et al., 2020). For this reason, most clinical providers in Canada are private health centers with their own organizational structures, charters, and management practices. It should be emphasized, however, that the increased autonomy of Canadian clinical providers does not mean that care delivery is disorderly: professionals adhere to the code of ethics and standards set by Medicare.

Notably, the Canadian healthcare system is characterized by a high degree of democracy for its citizens. Unlike other existing systems, Canadian Medicare provides health care to all legal residents regardless of their income level and socioeconomic status, which is one of the key principles laid down at the level of the federal healthcare administration. One manifestation of this concern for the population is providing a tax credit if a patient spends more than 3% of their income on health care, or $1,816 (here and hereafter, U.S. dollars). In such a case, the state provides a 15% tax credit that can be used to cover the remaining costs (Tikkanen et al., 2020).

Democratization is also realized by not having to pay for each visit to a doctor or clinic. For example, health care in the neighboring country of the United States is often discussed negatively by the public for paying for every doctor’s appointment. One such consultation appointment with a general practitioner can cost a patient up to $200, depending on the state: tests and follow-up appointments are paid separately (Lauretta & Hall, 2023). In Canada, however, one does not have to pay for every visit: Medicare usually covers most costs.

Medicare and other operating costs are based on a provincially or territorially mandated standard and are mostly tax deductible. Not all elements of the health care system are free or practically free for Canadian residents. Although Medicare covers basic services, it does not cover dental or eye care (Tikkanen et al., 2020). In addition, Canadian health care does not cover medications, so the financial burden of clinical care is not completely removed from residents.

Organizational Structure of Canadian HealthCare

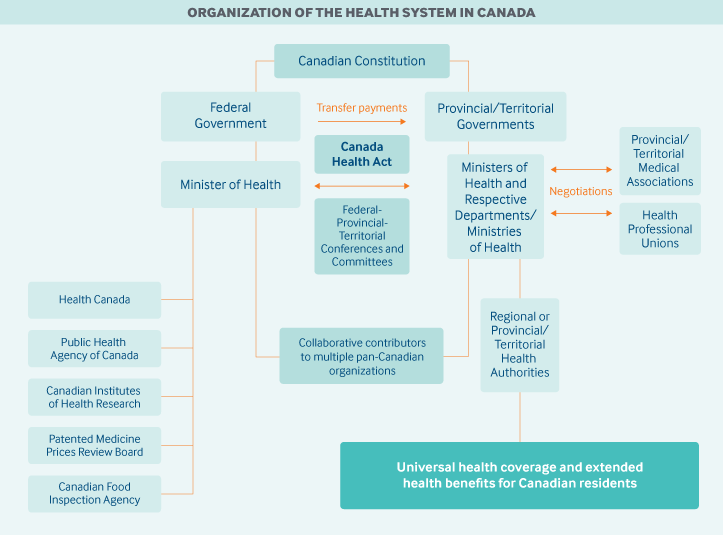

It is now understood that Canadian Medicare is implemented both at the federal government level, which assumes the role of regulator and at the provincial and territorial governments as implementing bodies. Tikkanen et al. (2020) report that the “primary responsibility for financing, organizing, and delivering health services and supervising providers” lies with provincial and territorial governments (para. 3). However, federal government responsibilities include “cofinancing P/T [provincial and territorial] universal health insurance programs and administering a range of services for certain populations, including eligible First Nations and Inuit peoples, members of the Canadian Armed Forces, veterans, resettled refugees and some refugee claimants, and inmates in federal penitentiaries” (Tikkanen et al., 2020, para. 4).

National health care in Canada is represented by several regulatory bodies, including Health Canada (HC), Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), and Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), as indicated in Figure 3. HC oversees compliance with federal Medicare guidelines, drug and food safety controls, and medical device inspections. PHAC is responsible for emergency preparedness, ensuring appropriate protocols are followed, and working on preventive measures and public health improvement programs. Finally, ISC aims to provide national care for the most vulnerable groups, which include Indigenous peoples.

Canada’s healthcare structure also includes non-profit and private insurance programs used by the local population. The government HI insurance program, performed under Medicare, covers all basic clinical services except purchasing medications, dental visits, and eye care services. According to the Government of Canada (2019), as of 2010, out of every ten dollars spent on health care, $7 was covered by the government, and the remaining $3 came from private sources, including patients’ money. According to the 2016 update, out-of-pocket payments decreased to $1.5 out of $10, predominantly spent on related medical services and nursing homes (Tikkanen et al., 2020). This decision substantially reduces the financial burden on patients because most medical services, including surgery and hospital operations, are free to patients.

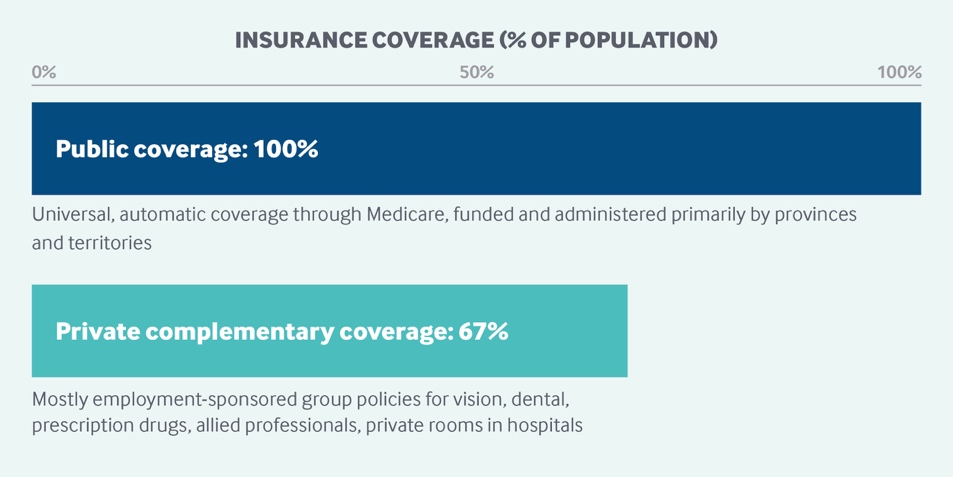

Notably, only legal residents of Canada are covered, so immigrants and tourists are not covered by HI. However, this does not mean that such visitors cannot use medical services: according to federal guidelines, healthcare providers cannot refuse clinical care to anyone, but without a valid HIC, visitors to Canada must pay their own medical expenses. Funding for public HI at the provincial and territorial levels comes primarily from taxes, and about 24% is funded through the federal Canada Health Transfer program (Tikkanen et al., 2020). However, in addition to public HI, residents can choose private insurance programs.

Private insurance covers more services, so it has the advantage of even being able to go to dental or eye care facilities. According to Tikkanen et al. (2020), about 67% of the Canadian population (Figure 4) choose private insurance plans, mostly due to employment restrictions. Private insurance is 90% funded through employers, i.e., with money directly from patients, and most insurers are for-profit (Tikkanen et al., 2020). It is important to clarify that if private insurance is available, the patient still does not pay directly for health care, but a subscription or user fee is deducted monthly or annually from wages. It follows that by giving some of the money for having a private insurance package, the patient acquires some of the tangible benefits discussed below.

In practice, there is a tension between the public and private insurance sectors based on the range of services covered or the implementation of medical practices. In particular, as Marrison et al. (2022) point out, the public insurance sector suffers because of ever-increasing healthcare costs as equipment, staffing, and associated operating costs become more expensive. Consequently, provincial and territorial governments, whose responsibility it is to fund HI, decided to abandon some of the services previously included in basic covered programs. This forces residents to switch to private plans, which still cover most health care.

In addition, the national healthcare system has a resource shortage problem, which is discussed in more detail in the next chapter. Long waiting times for hospital or clinical care can be a negative signal of Canadian healthcare efficiency, which also encourages Canadians to switch to non-pay private insurance plans. It is very important to note, however, that under Canadian law, private health insurance providers cannot offer services that duplicate public insurance programs (Government of Canada, 2019). In other words, private packages cannot be identical to public packages but must necessarily include additional services to comply with the law.

Canadian Medicare Performance Indicators

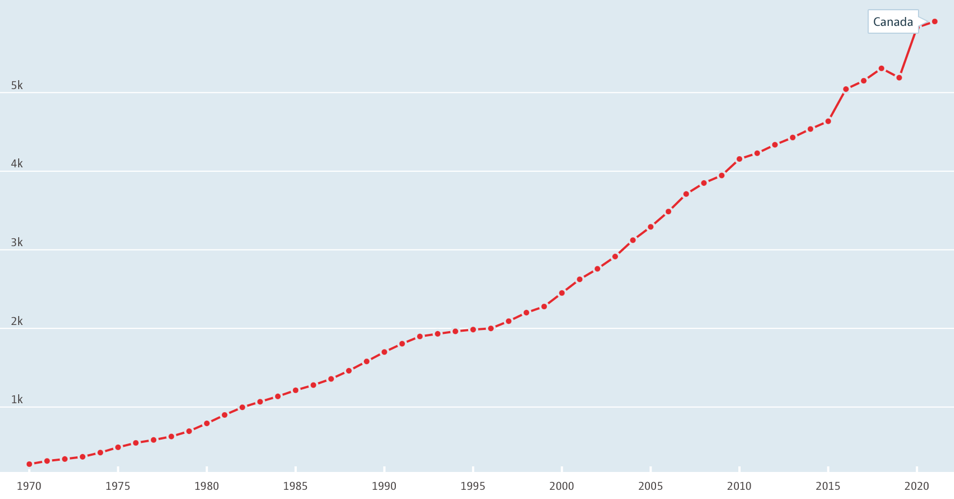

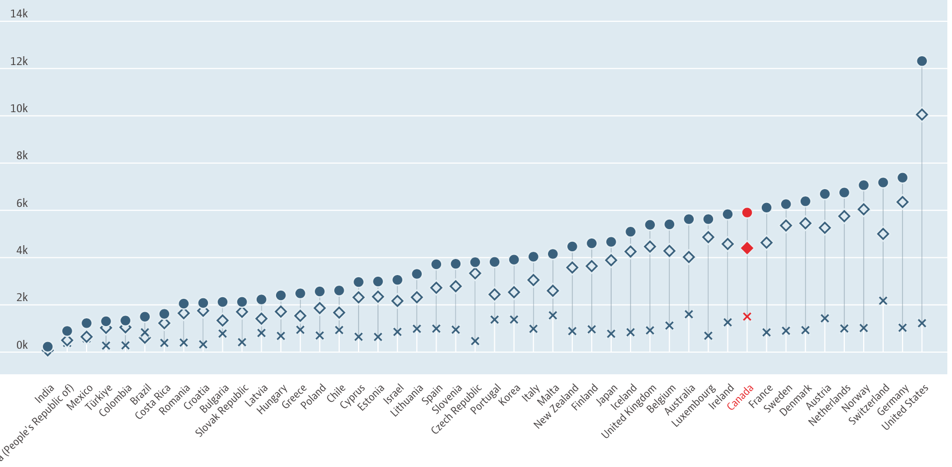

Canada’s public health care system is highly globally recognizable and renowned for efficiency. Its most obvious and tangible results are social health policy indicators, that is, specific metrics of the lives of the population. By way of background, one should refer to the fact that Canada’s current population is 38.2 million residents, and the national GDP is $57,100 per capita (OECD, n.d.). Canada spends $5.9 thousand per capita on health care, a figure that has risen steadily over the past 51 years, except for a drop in the pre-pandemic year (Figure 5). By comparison, in the context of global spending, as shown in Figure 6, Canada ranks in the top 10 countries, second only to some European countries with significantly lower populations and the United States.

Increased funding for health care brings tangible results for the population. For example, the average life expectancy of a Canadian is 79.5 years for men, 84.0 for women, and 81.7 without gender specifications (OECD, n.d.). On this measure, Canada significantly outpaces such world superpowers as the U.S. (77.0), Russia (73.2), the U.K. (80.3), and China (77.1). The average infant mortality metric, which demonstrates the effectiveness of the health care system, reports that Canada ranks 19th globally with only 4.5 cases per 1,000 births.

In terms of the average length of hospital stay, Canada ranks fifth in the global competition with an average of 7.7 days per person — a metric worth looking at from different angles. On the one hand, a shorter hospital stay reduces the risks of co-morbid infections and lowers treatment costs. On the other hand, however, longer inpatient stays may be associated with the need for more complex surgical interventions.

In the context of Canada, where the costs of treating patients are almost entirely covered by taxes, longer hospital stays can be both a positive and a negative signal. In synthesis with the fact that Canadian Medicare is characterized by 2.5 hospital beds per 1,000 population units, this can be seen as a negative signal: a longer length of hospital stay with a low number of hospital beds can lead to a shortage of medical resources for the rest of the population and the need for longer waiting times for treatment. On the other hand, it cannot be ruled out that these circumstances may indicate a low demand for hospital treatment in the Canadian population, provided that there is effective health promotion.

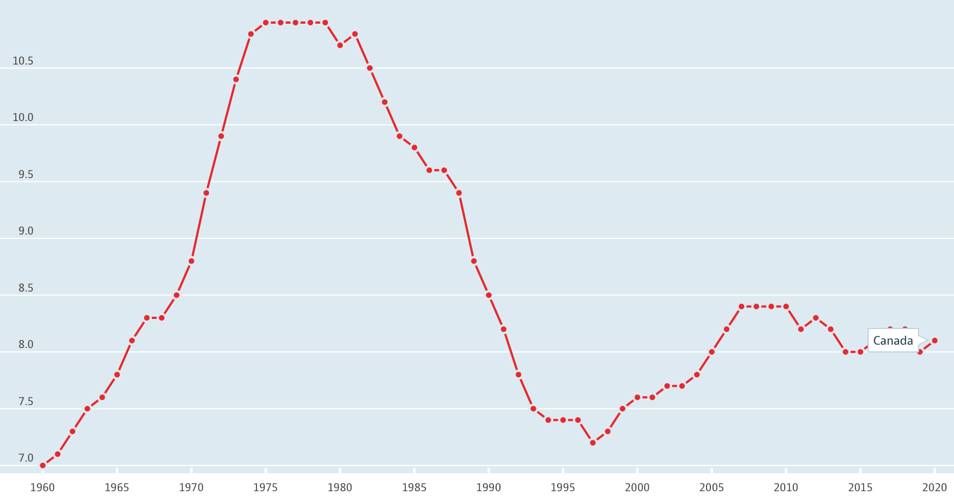

The above counterargument should be examined from the perspective of the unhealthy habits prevalent among the Canadian population. The OECD (n.d.) reports that the average alcohol consumption of Canadians is 8.1 liters per capita over the age of 15, a figure which is significantly lower than that of most other countries. Fig. 7 reports that over the last 50 years, this figure has fallen significantly but has increased compared to the level of twenty years ago.

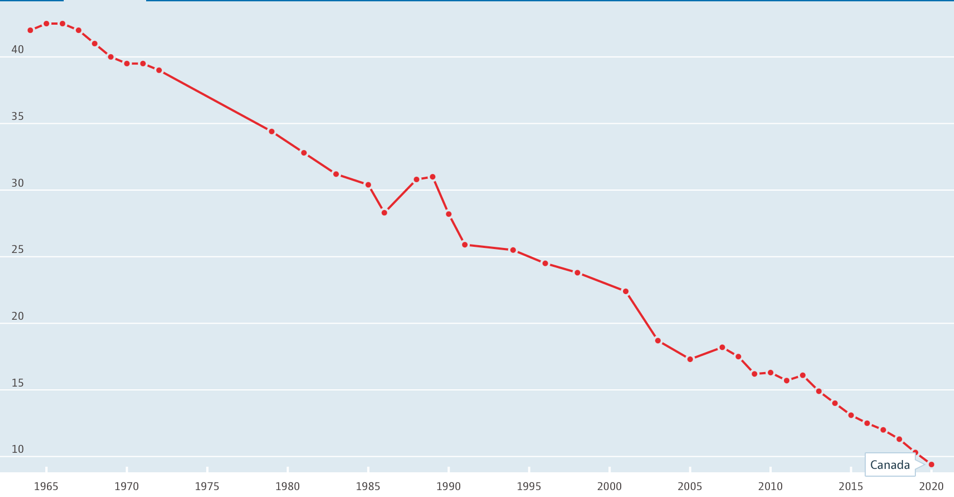

Similar figures are true for tobacco consumption: although Canada is not among the top countries for tobacco use, consumption has fallen significantly over the past 50-60 years, as shown in Figure 8. Obesity as a problem of overeating and unhealthy food consumption should also be considered in light of bad habits: Canada ranks 9th in the global ranking of countries, with 59.8% of its population being obese, with an increase of three percentage points in the obese population compared to almost twenty years ago. The results discussed above show that although there has been some success for public health in Canada in terms of promoting healthy lifestyles, a large proportion of the population still has unhealthy habits, and these rates (excluding tobacco smoking) have increased over the twenty-year observation period.

Differential Health Systems

As discussed above, the health care system is implemented at the provincial and territorial levels and is decentralized, although the national level adheres to Medicare standards. Marrison et al. (2022) vividly describe this phenomenon when they say that “Medicare is actually composed of 13 different health care systems” (para. 11). Differences in agencies lead to the formation of some discrepancies and differences in exactly how provincial and territorial governments and clinical organizations implement health care practices. The main factors to be taken into account are the region’s demographic and geographic conditions, budgeting, and policies.

The major differences implemented at the provincial and territorial levels are the insurance plans offered to the population, which vary in structure, reimbursement, and costs. Admittedly, it is up to each provincial or territorial government to determine the range of clinical services to be provided at no cost to the public. Decisions to include or exclude services are made at the highest legal level in discussion with stakeholders, whether local colleges, universities, hospitals, or social groups.

Thus, “If it is determined that a service is medically necessary, the full cost of the service must be covered by the public health insurance plan to be in compliance with the Act. If a service is not considered to be medically necessary, the province or territory need not cover it through its health insurance plan” (Government of Canada, 2019, para. 25). It is also up to local governments to determine who is eligible for benefits and to provide them with reasonable assistance. For example, a provincial or territorial government may decide on a personal basis that the region’s seniors will receive discounts or benefits on medicines.

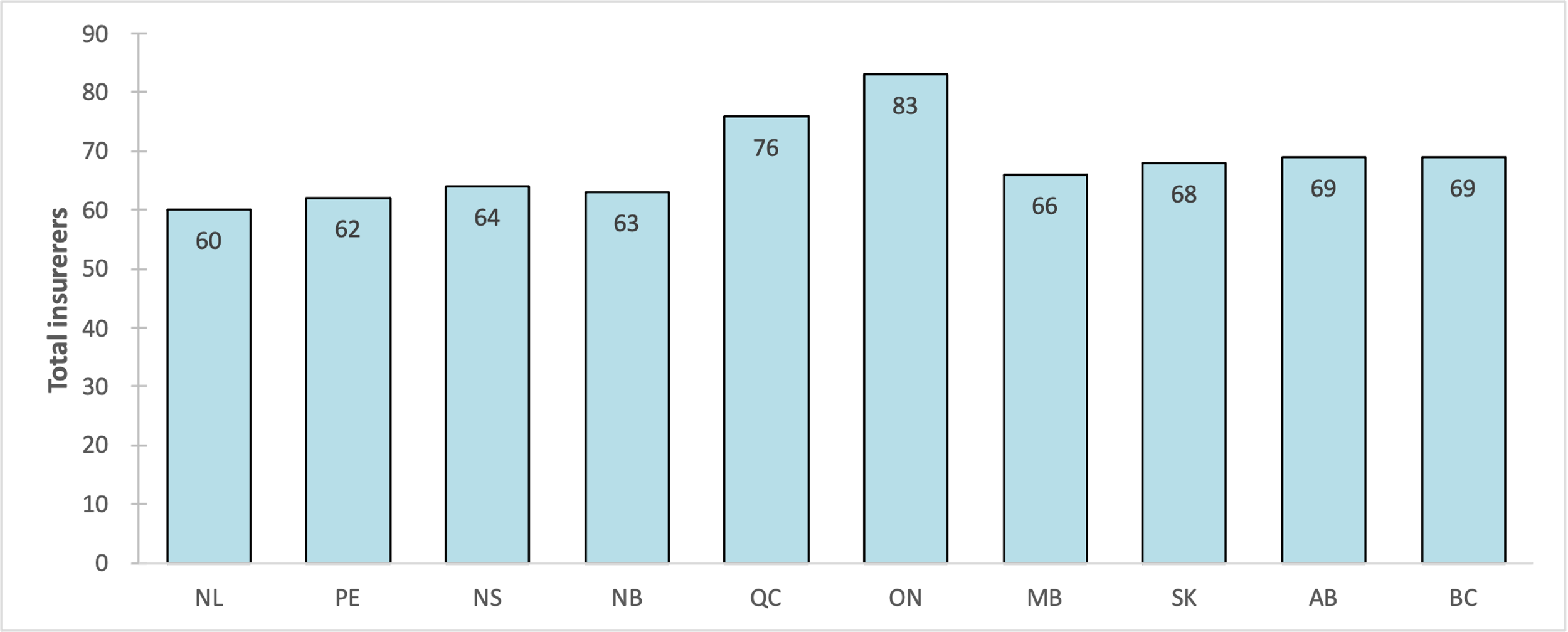

It makes sense to look at the differences among Canada’s 13 provinces and territories in more detail. Figure 9 shows the total number of insurers for each of the ten provinces, and it is clear that for Ontario, the figure is significantly higher than the average (M = 68). However, this comparison is not very meaningful because it does not take into account the population size of each province. Figure 10 presents the same metric but is measured at the level of percentages of the number of insurers as a percentage of the region’s total population. Thus, it becomes apparent that while the total number of insurers in Ontario is higher than the provincial average, the region ranks last when accounting for population: fewer insurers are available to the region’s population.

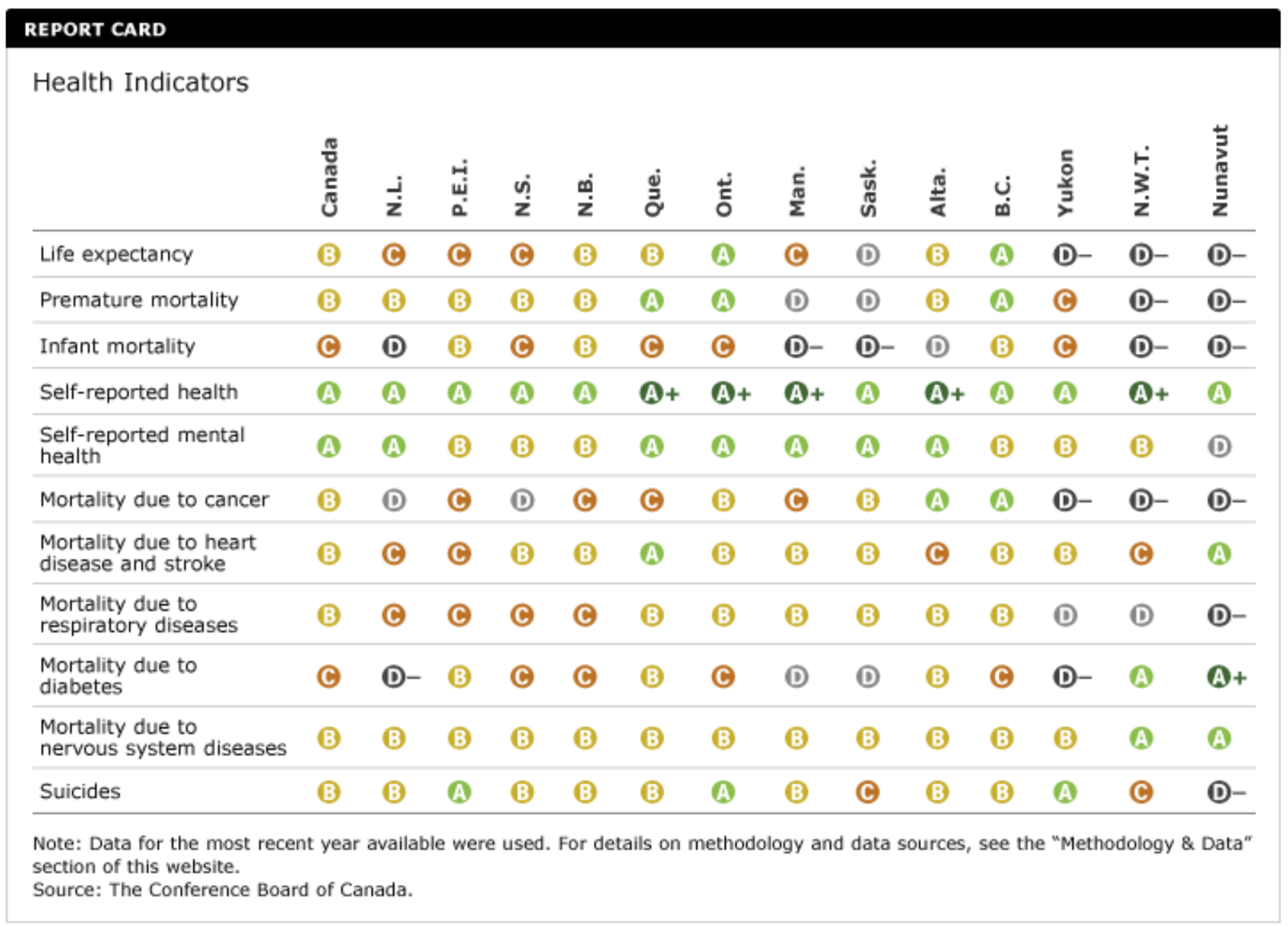

Figure 11 depicts additional statistics that show the total amount of investment each provincial government has spent on health care. Ontario, as Canada’s most populous region, ranks highest on this measure, spending $382 billion in 2021, which implies that this province has spent the most on healthcare needs. Figure 12 is a methodological assessment of each of Canada’s administrative regions based on the achievement of the sustainable health goal. The methodology for this assessment is based on six criteria (Economy, Society, Innovation, Environment, Health Education, and Skills), using the OECD sets as the data source (The CBC, n.d.). The standard educational system A-B-C-D is used for evaluation, and the assignment of a particular grade is based on statistical quartiles. Thus, a country is assigned a report card grade of “A” if its score falls within the top quartile, a “B” for the second quartile, a “C” for the third quartile, and a “D” for the bottom quartile. (The CBC, n.d., para. 14).

As the report card shows, the provinces of Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia were the best performers on the 11 metrics, while three territories did the worst in achieving sustainable health care, with Nunavut having the worst results. Assessing the results by specific metrics, Figure 12 shows that Ontario and Quebec did best in terms of life expectancy, while the three territories and Saskatchewan did worst in terms of achieving maximum life expectancy.

Notably, none of the regions scored high on the Infant mortality metric, but British Columbia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick performed best. Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia were the best performers in the premature mortality metric. The metrics for total mortality due to cancer, heart disease and stroke, respiratory diseases, diabetes, and nervous system diseases generally repeated the others, as Ontario, Nunavut, Quebec, British Columbia, Alberta, and Newfoundland and Labrador were best at achieving reduced mortality, while Prince Edward Island and Yukon were worst. Yukon and Ontario had the best relative health outcomes compared to the other jurisdictions in terms of the number of suicides.

Taken together, this points to the fact that, when taken together, provinces (especially Quebec, Ontario, and British Columbia) appear to be more effective at achieving sustainable health care than territories. Nevertheless, in terms of certain characteristics (such as suicide rates and mortality rates), some territories have been found to outperform individual territories. Combined with the fact that investment spending by Quebec, Ontario, and British Columbia was quite high, the results seem justified. Additional summary information on health system performance for each of the provinces and territories is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 — Data on health metrics by province and territory for 2021 (CIHI, 2023).

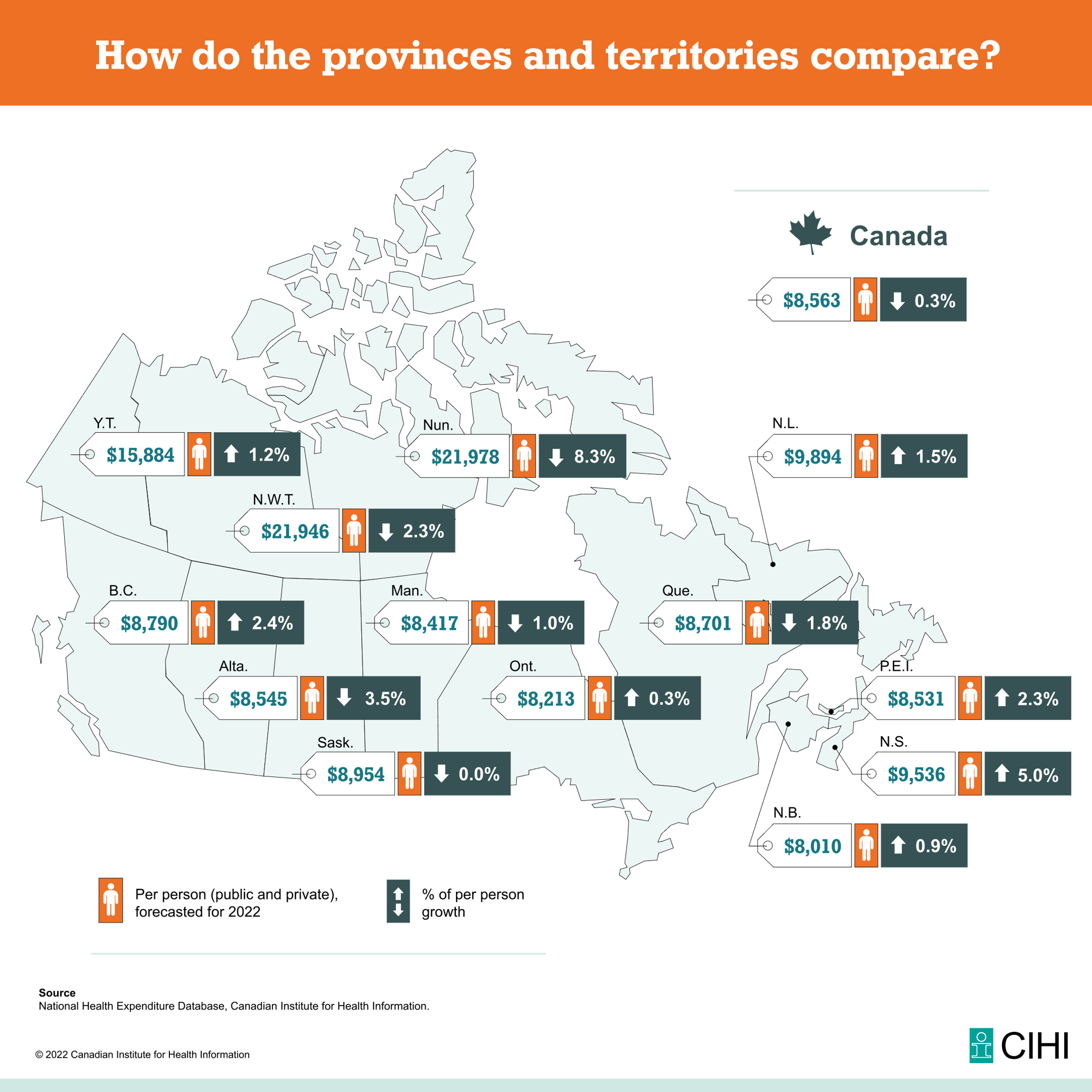

Of additional interest is the data on how healthcare expenditures are distributed by province and territory. As Figure 13 shows, compared to 2021, there was a decrease of 0.3% at the national level, but at the individual administrative unit level, there was a noticeable increase. Specifically, the provinces (Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, and British Columbia) and territories (Yukon) showed increases on the percentage scale, with per capita spending higher than the national level for Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, and British Columbia. Notably, all three Canadian territories had very high per capita health expenditures (CIHI, 2022). The reasons for this phenomenon could be the significantly lower population size, and the consequence could be increased access to health care and improved quality of care. However, revisiting Figure 12 shows that despite high per capita healthcare expenditures, the territories could be more institutionally efficient.

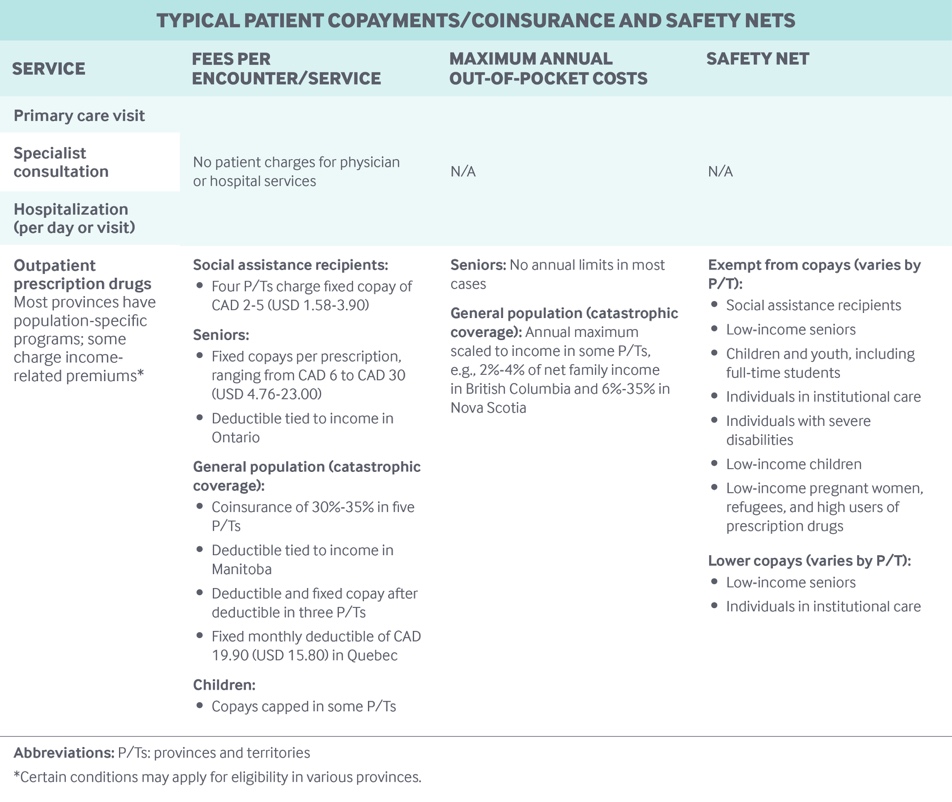

As noted above, Canada’s provinces and territories differ in the benefit policies that are provided to their populations. For example, benefits differ for vulnerable populations without private insurance. The province of Quebec requires the population to have private coverage, and only for those who cannot afford private insurance public care provided (Tikkanen et al., 2020). In Ontario, there is no such strict obligation, and authorities help vulnerable populations (senior citizens, children, and welfare recipients) through universal drug purchase programs. Figure 14 summarizes healthcare payment policies at both the national and administrative levels. As the data show, initial doctor visits, specialist consultations, and hospitalizations are not paid directly by patients at all provincial and territorial levels; however, payment variation then begins depending on the administrative unit.

Common Health Problem

One way to view the national healthcare system is to look at the key health problems prevalent in the population. According to UR (n.d.), the most common clinical health conditions are physical activity and nutrition problems, obesity, tobacco and alcohol use, HIV, mental health disorders, respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. UHS (2021) expands the list of these conditions by adding allergies, conjunctivitis, diarrhea, headaches, and gastrointestinal diseases. To be specific, it makes sense to compare rates to the U.S. in terms of the percentage of the total population.

Table 2 — Data on prevalent clinical conditions per percentage of the population (OECD, n.d.; CDC, 2023; Government of Canada, 2023).

It is clear from the data that compared to the U.S., the most prevalent conditions in Canada are alcohol use, drugs, obesity, depressive conditions, HIV, and tuberculosis, among those conditions described in Table 2. Without comparison, respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, various cancers, and diabetes remain the most pressing health issues in Canada. According to the Government of Canada (2017a), about one in five Canadians “live with one of the following chronic diseases: CVD, cancer, CRD or diabetes” (para. 3). In terms of psychological health, “one in 25 Canadian adults aged 20 years and older reported having a mood and anxiety disorder and at least one of the four major chronic diseases” (Government of Canada, 2017a, para. 3). Cancer is reported to be the leading cause of death in the Canadian population, with over 90% of all cancers occurring in the older generation.

Challenges for Canadian Health Care

In addition to examining the epidemiological data, it is useful to look at the institutional data of Canadian health care to discuss the key issues. As noted earlier in the text, because of the conflict between the public and private insurance sectors, Canadians are forced to have long waiting times to see a doctor or undergo surgery. This problem also follows a shortage of medical resources, including a shortage of hospital beds and medical staff.

Moir and Barua (2022) indicate that the average wait time between receiving a doctor’s referral and receiving medication is 27.4 weeks. It is noteworthy that this figure varies greatly between provinces and territories: for example, it is 20.3 weeks for Ontario and about 64.7 weeks for Prince Edward Island. Under these circumstances, the average number of physicians per 1,000 population units is only 2.46, which defines a significant overload (Paperny, 2023). Taken together, this results in a drop in the efficiency of Canada’s health care system.

The found differences in the implementation of health care tasks across provinces and regions create another problem of decentralization, namely differences in clinical access. Although federal law states that Medicare should be universal and affordable, in reality, patients from populous and infrastructure-heavy provinces have advantages in obtaining clinical care compared to those regions whose population and development are lower. Paperny (2023) also reports that 22% of Canadians do not have a primary clinical care provider, resulting in a lack of early diagnosis of chronic conditions and the occurrence of aggravations.

Among the additional problems of a national health care system that “has long been a source of pride… [and] has been strained to the breaking point,” Paperny (2023) cites increasing numbers of unnecessary hospitalizations, lack of timely care for seasonal infections, and decreased attention to the needs of territories. Against this background, the evidence that patient satisfaction with the care received has fallen over 19 years from 80.2% to 62.0% seems reasonable (Government of Canada, 2017b; CIHI, 2019). Thus, the Canadian healthcare system faces many challenges that, despite its existence as one of the most efficient, can negatively impact public health in the absence of preventive and reactive solutions.

Recommendations for Improvement

When it became clear that Canada’s health care system was experiencing serious congestion problems and could potentially lose its status as one of the most efficient, it was appropriate to develop some recommendations to improve the current circumstances. The CBC (n.d.) suggests a change in the focus of the health care system toward individualization and a commitment to cultural values. Culturalization of health care will help achieve desired health outcomes among indigenous and vulnerable populations, for whom tradition and history are of heightened importance. It is also suggested that health expenditures be increased for early detection programs due to the aging population trend, as chronic diseases and associated deaths would otherwise increase. However, it is not enough to only increase spending: the approach for patients must be personalized and data-driven in order to engage patients in the course of treatment and achieve high rates of recovery.

The current problems of insufficient medical resources and long waiting times can be solved by promoting medical education, automation, and optimization of healthcare processes. First and foremost, Canada needs to ensure a higher flow of graduates who will work in local clinical organizations. This can be achieved through tuition benefits and job security with above-market salaries. Active implementation of electronic medical records, streamlining processes, and reducing redundant hospitalizations, combined with the use of telemedicine, could also be useful steps to address these issues (Sutton et al., 2020). In other words, in order to improve current levels of health care in Canada, facilitating technological advances and increasing community interest in medical education are important steps.

Issues of unequal distribution of access in the national health care system also make sense in the context of a discussion of remediation. One way to achieve higher rates for the three territories is to provide additional funding and investment in specific healthcare facilities, with full transparency of cash flow. Looking at this problem comprehensively, additional budgets are needed to develop the entire infrastructure of such regions, which would, among other things, reduce the time it takes to get to a hospital in an emergency (Yoon et al., 2021). Subsidies and copayments can be provided for vacancies in remote regions in order to attract healthcare workers from developed centers to the outskirts of the country. Community outreach is important, namely increasing clinical awareness and health literacy by promoting healthy lifestyles and early disease detection.

It is important to note that the Government of Canada is not only aware of the problems that exist but is also committed to taking steps to address them. In particular, as indicated by the Government of Canada (2023b), four areas have been identified for work in the near future, the goal of which is to achieve sustainable health care. First, equitable clinical access to family health care systems is needed, including for remote regions of the country. Such services include increasing primary care capacity, expanding immunization plans and regular checkups, providing care for pregnant women and childbearing mothers, and promoting reproductive health. This level is made possible by investing in the expansion of primary health care and preventive care, as well as the development of family health institutions.

Second, the efforts of the Government of Canada are aimed at supporting medical workers who face overburdening of the health care system, which can lead to the development of professional burnout. Support can be implemented both on material and mental levels, and the main goal is to ensure the importance, value, and motivation of each employee in the industry. A third way forward is to increase public awareness of the psychological support options available for substance abuse, alcohol, and tobacco. Increased institutional resources should help to ensure that different members of society have equal access to high-quality medical support. The last priority of the Government of Canada is to modernize the health care system. This includes digitizing and enhancing the technical capacity of clinical organizations, as well as ensuring that patients and providers have access to electronic information.

Conclusion

Critical appraisal of national health systems is an important step in identifying strengths and weaknesses as well as discussing promising measures for improvement. One of the learning outcomes of the Health Insurance & Health Policy course is to develop competence in a comprehensive and critical appraisal of health systems, and Canada was chosen for this paper. In fact, Canadian health care (Medicare) should be viewed as a collection of 13 separate systems because of its high degree of decentralization and variation.

The paper showed that Medicare could be considered one of the most efficient on a global level and highly democratic since federal principles guarantee free clinical care to all residents. According to Medicare principles, residents do not have to pay directly for receiving medical care since this is covered primarily by the tax base. However, it is fair to recognize that a large proportion of residents are carriers of private health insurance because it provides additional benefits. Although this insurance format forces patients to pay a monthly or annual subscription fee, which is usually levied on wages, it opens up access to many services in the Canadian healthcare system that have been excluded from free care: dental or ophthalmic care, for example.

The paper discussed in detail the differences among Canada’s 13 provinces and territories, which are realized both at the level of internal processes and in terms of performance indicators. One of the main findings was that provincial levels of health care were higher for Quebec, Ontario, and British Columbia, largely due to higher rates of investment in the system and better infrastructure. Meanwhile, territorial health care was among the lowest performing, although it should be noted that it was quite high on individual metrics. Differences were also found at the level of provision of benefit programs: provinces and states have different systems of surcharges for patients, as well as different conditions for providing benefits to vulnerable groups.

In recent years, including because of the pandemic, healthcare has faced many challenges. These include healthcare congestion, deteriorating clinical access, labor shortages, and anticipated declines in patient satisfaction. High Medicare congestion leads to longer waiting times, which in some cases can be more than a year.

Obviously, under such circumstances, achieving high performance in the healthcare system is questionable. To correct the current circumstances, the problems should be considered comprehensively from a cause-effect paradigm. Thus, the paper proposed recommendations to correct the existing problems, which include automation and optimization, increasing public interest in medical education and clinical awareness, as well as increasing costs.

References

CDC. (2023). Diseases and conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web.

CHLIA. (2022). Canadian life and health insurance facts, 2022 edition. CHLIA. Web.

CIHI. (2019). Patient experience in Canadian hospitals, 2019. Canadian Institute of Health Information. Web.

CIHI. (2022). How do the provinces and territories compare? Canadian Institute of Health Information. Web.

CIHI. (2023). Data tables. Canadian Institute of Health Information. Web.

Government of Canada. (2017a). How healthy are Canadians? Government of Canada. Web.

Government of Canada. (2017b). Archived — Patient satisfaction with most recent hospital care received in past 12 months, by age group and sex, household population aged 15 and over, Canadian Community Health Survey cycle 1.1, Canada, provinces, and territories. Government of Canada. Web.

Government of Canada. (2019). Canada’s health care system. Government of Canada. Web.

Government of Canada. (2023a). Health data in Canada. Government of Canada. Web.

Government of Canada. (2023b). Improving health care. Government of Canada. Web.

Lauretta, A., & Hall, A. (2023). How much does therapy cost in 2023? Forbes. Web.

Mappr. (2021). Canadian provinces and territories. Mappr. Web.

Marrison, A., Ozembloski, J., Ryan, H., & Webster, H. (2022). No quick fix: Private health care in Canada is back in the news. BLG. Web.

Moir, M., & Barua, B. (2022). Waiting your turn: Wait times for health care in Canada, 2022 report. Fraser Institute. Web.

OECD. (n.d.). Canada. OECD Data. Web.

Paperny, A. M. (2023). Explainer: What ails Canada’s healthcare system? Reuters. Web.

SC. (2022). Age pyramids. Statistics Canada. Web.

SC. (2023). Population and demography statistics. Statistics Canada. Web.

Sutton, R. T., Pincock, D., Baumgart, D. C., Sadowski, D. C., Fedorak, R. N., & Kroeker, K. I. (2020). An overview of clinical decision support systems: Benefits, risks, and strategies for success. NPJ Digital Medicine, 3(1), 17-27. Web.

The CBC. (n.d.). Methodology. The Conference Board of Canada. Web.

Tikkanen, R., Osborn, R., Mossialos, E., Djordjevic, A., & Wharton, G. A. (2020). International health care system profiles: Canada. The Commonwealth Fund. Web.

UHS. (2021). Common illnesses. Princeton University Health Services. Web.

UR. (n.d.). Top 10 most common health issues. University of Rochester: Medical Center. Web.

Yoon, S., Kim, T., Roh, T., Chang, H., Hwang, S. Y., Yoon, H., & Cha, W. C. (2021). Twelve-lead electrocardiogram acquisition with a patchy-type wireless device in ambulance transport: Simulation-based randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 9(4), 1-10. Web.