As is often the case, literary works, or any other form of “text” with broad appeal cannot be evaluated from only one perspective. There are a considerable number of people living on the planet, and each of them has its own cultural and ethnic background. The presence and quality of this background, or experience, determines an individual’s attitude toward a particular “text. At the same time, not all authors are inclined to give direct answers to the questions posed in the work. It is believed that if a question has not been answered directly, but the audience has been able to learn the correct answer through hints and analysis, such a “text” has the quality of unique genius. This paper takes as such a work of genius the fall series from Netflix, The Squid Game, which in less than a month was able to achieve enormous popularity around the world. Statistics show that one in every 70 or so people in the world has already watched the series (Burke). Several interesting factors were the reason for choosing this work for analysis through the prism of reader-response criticism. First, it is personal familiarity and interest in this television series. Secondly, it is a South Korean production, and it has managed to become popular worldwide. Thirdly, there are many details hidden in the “text” that are interesting to explore in more depth. Thus, The Squid Game is a good material for analysis through reader-response criticism, which is the purpose of this essay.

A bit of theory regarding Reader-Response Criticism must be said first in order to understand more clearly the meaning of this paradigm. It is one of the few strands of textual criticism that focuses not on the author or the content of the work but on the reader (Tyson 180). This criticism operates with categories such as reader experience, perception, and interpretation, and thus it is one of the most subjective forms of criticism. It is as if the reader brings the story to life as they encounter the story, and any uncertainties allow this familiarity to be made more complete. For example, authors of “texts” may introduce details or elements into their works (e.g., Chekhov’s Gun) that do not make much sense when they first appear. This generates many theories and conjectures as to their meaning. To use a very crude example, the viewer of a television series, while watching, is constantly discussing what will happen next, trying to guess. Authors can either provide answers to these uncertainties or leave them that way, forming an open finale and a horizon for other theories. In her book, Tyson gave an example of six reader-response criticism logic questions that allow for deeper analysis of the text. For the discussion of the new series, The Squid Game, the first question is chosen, which is precisely aimed at exploring the birth of meanings on the collision of uncertainty and client perception.

The brief plot of the TV series is that a group of 456 poor Koreans with huge debts receive an invitation to an unknown game in which they have to fight for survival. The surviving participant receives 45.6 billion Korean won, the equivalent of $38.5 million. The participants face a series of six games, after each of which their numbers dwindle: those who fail in the game die. The series raises many social themes, be it capitalism and poverty, human relations and greed, and hypocrisy. Thus, this “text” reflects the actual agenda for modern viewers, which is one of the reasons for the increased popularity of the work.

What is even more interesting is that there are many of Chekhov’s guns that were not explicitly covered in The Squid Game but whose use became increasingly evident as one became more familiar with the story. One of these is, in fact, the theme of the games themselves, that is, what the next game would be. The principle of game selection was based on children’s Korean hobbies, so both the characters in the work and the audience guessed what might be next. This raised doubts and questions and allowed the foreign viewer to get deeper into the ideas of Korean childhood eventually. Interestingly, in the latter episodes, the issue with the themes of the games, when most of them had passed, was no longer pressing: the walls of the room in which the participants slept were marked with a picture of each of the rounds, as shown in Figure 2. Thus, the experience of this interaction with the viewer is based on the profound uncertainty that binds all the series and on the consistent resolution of it.

In addition, one of the most accessible rhetorical tools that can be used by the authors of the “text” is the intentional mystery. In relation to the series, many phenomena and faces are mysteries, but the main one is the identity of the Game Master (Figure 3). The man in the black mask does not take it off until episode 8 and does not let the viewer know who is hiding underneath it. In turn, this becomes a push to guess, based on already existing experience of familiarity with the plot. Perhaps it is the man from the subway who gave the participants a business card, or maybe it is an unknown person who is yet to reveal himself. When the line of a police officer looking for his brother appeared in the story, it became predictable for many viewers that the two lines intersected. The lost brother and the unknown masked man are the same people, and this fact is confirmed in episode 8. Thus the direct adjustment of perception that Tyson wrote about (Tyson 180) is noticeable. Initial thoughts and doubts are gradually edited and directed, which improves the connection between the content and the viewer.

There are many more examples of uncertainty in this work that might first appear. Some of them have never been answered, which was the reason for the formation of an open ending with regard to the storylines. For example, one of the main rules of this series in terms of directing is the impossibility of accurately predicting a person’s death until it has been shown in the frame: this only works for critical characters. Thus, the death of participant 001 generated much emotion and became a topic of discussion on the Internet, as shown in Figure 4. However, as such, a shot with the death of Grandfather 001 did not exist because of the cunning of the camerawork: as a result, the elderly participant turned out to be alive and, moreover, he was the creator of the game. For the story was an example of a twist, where the initial viewer perceptions are entirely restructured and replaced by new emotions. Henceforth, Grandpa 001 is not pitied, but his behavior — wanted to have fun before he died and watch bloody games — is perceived as horrible, anti-human, and immoral. This is an excellent example of interacting with the viewer’s experience and managing perception. The presence of this example, in turn, raises apparent doubts about the death of the police officer who was murdered by his brother. His death was not shown in the frame, but instead, he fell from the cliff into the water. Given the incompleteness of his plot and the potential for such an outcome, it is likely that the police officer survived and will become a key figure in season two. In fact, this is the next level of dealing with viewer perception: Netflix knew for sure that after the Grandpa 001 story, audiences would extrapolate his outcome to the police officer so that they could predict similar theories.

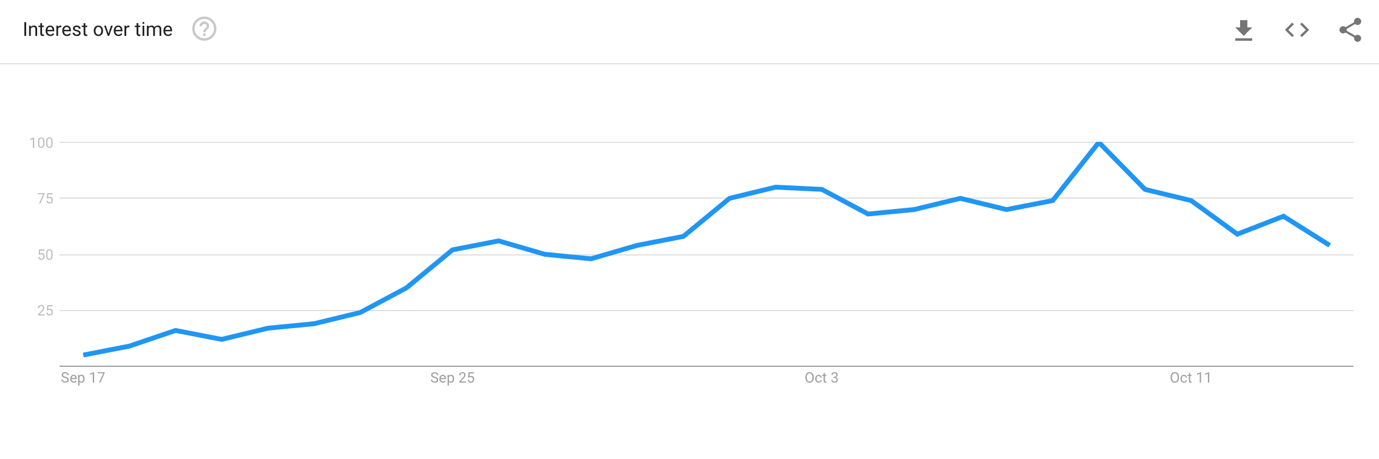

In fact, after watching all nine episodes, most of the questions have been answered, but many other doubts have also been created. In particular, it is still unclear who the soldiers in the pink suits are, whether the main character will be involved in season two, and the possible kinship between Grandpa 001 and the protagonist has not been determined. These and many other questions keep The Squid Game relevant even after the familiarity of the piece is over. Thus, even after finishing watching this series, viewers continue to discuss it and share theories, which increases the popularity and engagement of the audience. One of the leading platforms for expressing thoughts was just TikTok, through which the series was actively promoted. It is impossible to say for sure if this was a marketing strategy or if it was the will of the audience, but Netflix achieved its goals: people started to talk about the series a lot. Although the work came out as early as September 17, 2021, the popularity of Google searches for that keyword has been and continues to grow, as shown in Figure 5. Including millions of viewers were left puzzled and in doubt about critical issues: on the one hand, they are waiting for the story to continue, but on the other hand, the story can already be seen as a completed chapter.

A significant media content producer like Netflix knows precisely what feelings and emotions viewers will have after watching it and actually manages it well. By now, the series has an unfinished finale, with the central cast member 456 giving up his daughter’s trip to the U.S. for another bloody game. At this point, the series concludes, and the viewer finds himself in another bout of doubt: what happens next, whether he gave up the plane, why he decided to return to the games, and whether he can win again. In directing, this artistic device is called a cliffhanger, and it is an excellent summary of how meaning is made when plot uncertainties and human perception are combined. Cliffhangers are necessary to keep the viewer engaged, to create a more emotionally informative work and a more dynamic narrative. In this context, it was evident that the incomplete finale of The Squid Game is an intentional act by the authors, realized not because they do not know how to end the series but because they know how to do it.

In conclusion, it is worth emphasizing that exploring “texts” through viewer experience is one of the most subjective and biased forms of criticism because it always requires involving the personal feelings, thoughts, and experiences of the audience. Text authors understand this very well and use it in their work to heighten the emotionality and tragedy of the moment. Released in September, the series The Squid Game from significant media conglomerate Netflix is an excellent example of how “text” writers can interact with the client through understatement. With a lot of mystery, omissions, and missing descriptions, the director was able to create an environment in which the viewer is in a phase of constant guessing and doubt. This applies not only to the general idea of the series but also to the finer details. Since the entire work is built on the death of the participants, since only one will win, the permanent question of all episodes is to determine who will die in this series. In terms of reader-response criticism, this kind of connection is an unbeatable tool for holding the viewer’s attention. In addition, the series has some uncertainty about the storylines of critical characters, which creates a wave of discussion about the second season. However, even if the work does not get any sequel, The Squid Game has already accomplished its goals: telling the story, bringing in record profits, and conveying South Korean culture to the world.

Works Cited

Burke, Minyvonne. “’Squid Game’ Reaches 111M Viewers, Becoming Netflix’s Biggest Debut Hit.” NBC News, 2021.

Koreaboo. “Here Is The Hidden Easter Egg In “Squid Game” That Is Going Unnoticed By Everyone.” Koreaboo, 2021.

Kundu, Tamal. “Who Is the Masked Man in Squid Game?” The Cinemaholic, 2021.

Scribner, Herb. “We Watched ‘Squid Game’ in Case Your Kid Wants to Watch It.” Deseret, 2021.

Tyson, Lois. Critical Theory Today: A User-Friendly Guide. Routledge, 2015.