Introduction

The Chinese market is earning increasing recognition for offering unlimited opportunities to global corporations, spurring massive inflows of foreign direct investment. This trend is attributed to several socio-economic and political developments in China, including increased adoption of the rule of law, sound institutional reforms, and high research and development (Cai et al., 2019). Other economic advantages of doing business in this country, such as cheap labor and technological advancement, have served as incentives for corporations from principal trading partners such as the United States and European countries. However, despite China’s unlimited potential for international trade, foreign multinational corporations (MNCs) face unique cultural challenges due to the cultural distance between the two regions. This paper discusses some of the significant cultural issues that expatriate managers for United States (US) corporations face in China.

Hofstede’s and Trompenaar’s Cultural Dimensions

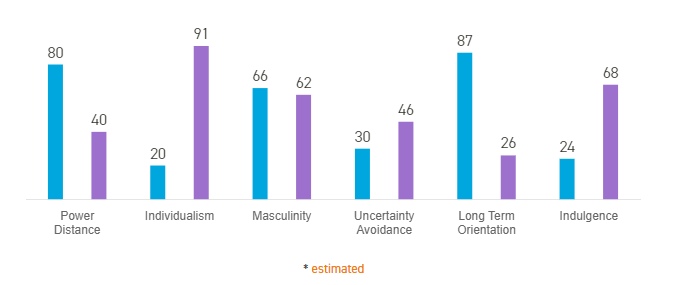

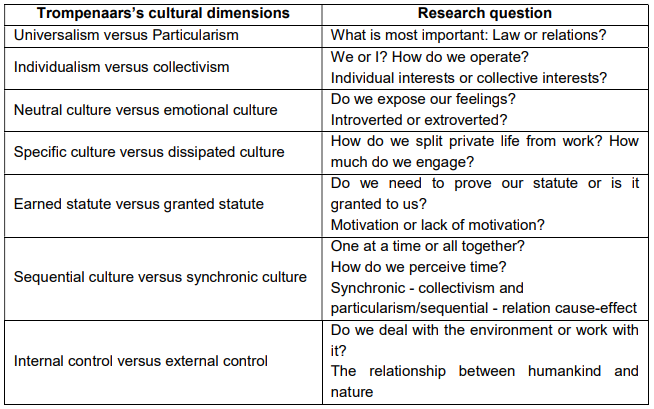

Hofstede’s and Trompenaar’s cross-cultural frameworks are the most recognized and widely used theoretical tools for comparing and analyzing national cultures. As depicted in Figure 1 and Figure 2, both frameworks are structured based on a set of cultural dimensions that provide insights into the fundamentals of cultural differences and nations’ dynamic culture. The discussion employs Hofstede’s and Trompenaar’s cultural dimensions to offer practical examples of how managers from US multinational companies struggle to adjust to the unfamiliar Chinese corporate business environment.

Cultural Issues US Managers Face in China

The first major cultural issue an American manager must face in China relates to the use of power. With a score of 80, China ranks higher on power distance, meaning that organizations clearly define management and subordinates (Carolina, 2019). A manager from a low power distance culture like America may find it challenging to accept inequalities, paternalistic and autocratic governance structures, polarized relationships between superiors and subordinates, and robust top-down management processes. American expatriates believe in collaborative leadership, equal distribution of power, and democratic decision-making processes and are less concerned with status (Leach-López et al., 2019). For instance, an operations manager working for an American MNC based in China almost resigned due to the inability to gain the respect of his superiors and subordinates (House et al., 2004). The manager failed to recognize that responses such as ‘I don’t know and refusing to help junior employees are unacceptable among Chinese who perceive managers as the company authority with all of the answers. Therefore, American managers struggle to work within rigid hierarchical structures and develop close relationships that encourage junior employees to ask for and get support from their managers.

The second cultural challenge is navigating the collectivist values that define the Chinese culture. With a score of 91, the US is a high individualist nation. This ranking implies that Americans look after themselves and their immediate family, prefer making decisions with minimal consultation, perceive themselves as autonomous from the company, and identify in terms of ‘I’ (LaBrie et al., 2018). As a result, a US national leading Chinese workers may experience a hard time operating within shared values that emphasize close relationships and identification with other team members. A US national with an individual orientation may strain to adapt to the solid in-group identity and commitment, which describe the tendency to forego personal interests to pursue the affiliated group’s goals (Carolina, 2019). The most challenging part would be understanding and acclimating to in-group considerations when making decisions related to hiring and promotions since the Chinese prioritize family members and close friends when making such decisions (LaBrie et al., 2018). Another grueling experience for US-born managers is getting issued to the cold or even hostile treatment to out-groups.

Chinese firms integrate Confucian values and norms into their corporate cultures. Confucian ethics provides the moral foundations of Chinese business managers’ behavior in relation to corporate social responsibility (Wang & Sun, 2018). These findings support the corporate scandals committed by prominent MNCs such as McDonald’s and KFC in China (Zhu et al., 2017). For example, in 2012, Chinese employees working for McDonald’s Sanlitun branch exposed the company’s attempts to sell expired food (Zhu et al., 2017). In the same year, host country nationals working for KFC reported the company raised chicken to maturity within 45 days and fed them growth hormones to mature faster and enhance their weight (Zhu et al., 2017). The disclosure of McDonald’s’ and KFC’s unethical practices demonstrates Chinese workers’ strong commitment to in-groups at the expense of the organization. Carolina (2019) explains that strong loyalty is fostered at work and in all aspects of the Chinese culture. In light of this cultural dimension, the Chinese believe that the needs of the group outweigh personal desires. Such concepts will be foreign to a Western expatriate managing a team in China.

Furthermore, A US-born manager working in China may find Chinese controlling less approachable, and mistrust in their colleagues and subordinates arduous. Unlike US managers, Chinese corporate leaders do not trust their team members; thus, they are likely to delegate to their subordinates (Caroline, 2019). An expatriate manager for an American MNC may find it challenging to work effectively with a Chinese colleague who epitomizes high uncertainty avoidance attributes. For example, an expatriate talent management executive for a US corporation operating in China struggled to work with a Chinese manager who was unwilling to relinquish control over human resource management tasks and projects within his responsibilities. The Chinese executive exhibited little confidence in the US counterpart’s abilities to ask for clear delineation and power-sharing patterns to avoid facing a brutal confrontation (House et al., 2004). These cases highlight the unique challenges managers of American-based MNCs sent to international assignments in China face due to the cultural distance between the two national cultures.

The malpractices by KFC and McDonald’s show that foreign MNCs in China do not portray Christian values. The major Christian principles breached in these cases are justice, integrity, honesty, compassion, discipline, and accountability. From a Christian ethics perspective, the unethical practices show that the corporations are not committed to upholding strong moral and ethical values. For example, the managers of these companies bend the rules or attempt to circumvent rules for material gains. This wrongdoing is reflected in the tendency to lie to consumers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, considering the limited national leadership experience in the Chinese market, many corporations turn to their expatriates to provide technical expertise or lead teams in the host countries, which creates excellent career advancement opportunities. However, the considerable cultural distance between China and countries in the Americas and the European region creates unique challenges for foreign business leaders who are sent for international assignments in China. Therefore, there is a strong need for US-based multinational corporations to prepare their managers adequately before sending them to Chinese corporate world.

References

Cai, H., Boateng, A., & Guney, Y. (2019). Host country institutions and firm-level R&D influences: An analysis of European Union FDI in China. Research in International Business and Finance, 47, 311-326. Web.

Carolina, T. (2019). Dimensions of national culture–cross-cultural theories. Studies in Business & Economics, 14(3), 220-230. Web.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (Eds.). (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Sage publications.

LaBrie, R. C., Steinke, G. H., Li, X., & Cazier, J. A. (2018). Big data analytics sentiment: US-China reaction to data collection by business and government. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 130, 45-55. Web.

Leach-López, M. A., Leach, M. M., & Lee, E. (2019). Culture convergence of manufacturing managers in Mexico, Korea, Hong Kong, and USA. Journal of Research in Emerging Markets, 1(2), 16-32. Web.

Wang, X., Li, F., & Sun, Q. (2018). Confucian ethics, moral foundations, and shareholder value perspectives: An exploratory study. Business Ethics: A European Review, 27(3), 260-271. Web.

Zhu, L., Anagondahalli, D., & Zhang, A. (2017). Social media and culture in crisis communication: McDonald’s and KFC crises management in China. Public Relations Review, 43(3), 487-492. Web.