Abstract

This paper examines the relationship effects of debt burden on sustainable economic growth using Nigeria as a case study. The country-specific investigation aims to demonstrate how countries’ debt management practices may influence their ability to utilize this resource to spur economic growth. The current analysis of Nigeria’s public debt is done by analyzing its economic statistics from the year 2009 to 2019. The researcher sourced data from the World Bank database and the Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) technique was employed to estimate the overall effect of the country’s’ external debt on economic growth. Two sets of variables emerged in the model: independent variable – debt and dependent variable GDP growth. The model was controlled for population, inflation, employment levels, labor and exports.

The present investigation emerges from a background of a rising debt burden among many African nations and growing concerns about their ability to use these funds effectively and still service the loan facilities. The present discussion will include an analysis of systemic risks and domestic vulnerabilities that a huge debt burden would have on a developing country, such as Nigeria. The findings of this analysis are useful in understanding debt trends among developing countries and the efficacy of governments to use the funds to spur economic growth. The findings are also important in developing fiscal management policies for guiding debt management practices in emerging economies. The investigation also provides an updated understanding of debt management practices in Africa, thereby creating a platform for reviewing how its growing economies can better improve the lives of its citizens by using debt as a tool for spurring economic growth.

Rising Sovereign Debt in Emerging Economies

The rising levels of sovereign debt have been a cause of concern for the global economy due to the risk it poses to the economic sustainability of nations. Coming from the aftermath of the 2007/2008 economic crisis, western nations have been leading others in accumulating some of the highest levels of debt seen in more than half a century to rebuild ailing industries (Abbas & Rogoff, 2019, p. 2). Developing countries have also adopted the same model, with debt vulnerabilities emerging as a point of concern among economists, given that some of these countries are on the verge of defaulting on their debt obligations while others have already done so based on their existing debt profiles (Al-Gasaymeh, 2020, p. 1). Reports by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) paint a grim picture of this situation, with their findings suggesting that most emerging economies are in severe debt distress (United Nations, 2020). The focus on emerging economies has been informed by the inadequacy of resources needed to balance debt and developmental needs.

Africa has recently attracted the attention of scholars interested in understanding the impact of loans on emerging economies due to the rising debt levels in many countries (International Monetary Fund African Department, 2021, p. 1). For example, the indebtedness of African nations to the Chinese government has been a cause of concern among observers because of skeptics who question the economic sustainability of the loans taken, given that many African governments are yet to demonstrate tangible results for the current stockpile of debt they have (Raudino, 2016, p. 21). The increase in debt is a paradigm shift in the management of economic affairs in Africa from one that is dependent on aid to another that seeks to promote self-sufficiency.

International lending partners have been willing to lend money to African governments, in line with this new economic approach, but with strict conditions on how such finances should be managed (International Monetary Fund African Department, 2021, p. 1). Additionally, governments have more options to source for money, compared to previous years, given that some creditors are willing to give loans at low-interest rates (Hussein et al., 2021, p. 1). Relative to this development, there has been a keen interest by some nations, such as China, to lend both financial and technical support to African governments, partly through debt, to support their economic growth objectives (Raudino, 2016, p. 105). Based on this development, many African governments have developed ambitious economic programs and plans to create jobs and improve the lives of their citizens.

By taking debt, governments hope to bridge the gap between their revenues and expenditures in government budgetary processes. Although there is the potential danger of default and insolvency, debt may be unavoidable to some governments because of its potential to attract investments by creating the right environment for trade (Saungweme & Odhiambo, 2021, p. 132). Consequently, debt financing is an important resource for managing a country’s economy because it provides additional sources of funds, besides government revenue, to meet short-term and long-term economic growth objectives (Croissant & Millo, 2018, p. 1). Therefore, when used wisely, it could help nations to spur economic growth and improve inclusivity in the management of their economic affairs, but when mismanaged, it could create economic crises and erode investor confidence (Abbas & Rogoff, 2019, p. 7). Therefore, it is important to manage debt efficiently to avoid the risks that come with it.

Relationship between Debt and Economic Growth in Emerging Economies

It is difficult to measure the effects of debts on economies due to a multiplicity of factors. For example, cyclic adjustment of fiscal balances by various types of governments could impact debt utility in a nation (Cevik, 2019, p. 4). Therefore, the use of debt has implications on people’s lives and their economies through its effect on taxes and household expenditures. This relationship draws attention to the need to adopt prudent use of debt management techniques as instruments of economic control and management because they could spur economic investments if used effectively and efficiently (Bhattacharya & Ashraf, 2018, p. 137). However, some governments use debt inappropriately, while, in some instances, changes in macroeconomic policies have made it difficult to service existing financial obligations (International Monetary Fund African Department, 2021, p. 7). These actions are detrimental to economic growth and development because debt is supposed to spur economic growth and improve the lives of its citizens.

High levels of debt in selected African countries have raised concern about the economic sustainability of such loans because of the lack of a commensurate rate of economic growth to justify them (Raudino, 2016, pp. 133). Additionally, there is scanty information about the effects of debt on African economies and whether the money sourced has achieved their intended purpose, or not. Stemming from this background, of immediate concern is the lack of evidence showing how African countries are using debt. The failure to understand their fiscal management policies undermines the role of debt in helping emerging economies to meet their developmental objectives (Cevik, 2019, p. 1). Of greater importance to this discussion is the potential that poor management of debt could lead to economic losses and poor services if funds that should be used towards financing programs or services to improve human welfare are redirected towards debt payment and servicing.

Based on the above concerns and the lack of adequate data to address them, there is a knowledge gap regarding the justification for taking sovereign debts and the process of allocating the same resources to areas that should spur economic growth. The growing appetite for economic development through loan financing in several African states has further made it difficult to interrogate these issues due low levels of accountability, and increased availability of lending options (International Monetary Fund African Department, 2021, p. 9). Consequently, questions have been raised regarding whether African countries can sustain these debts and if they are spurring economic growth, as they should.

Nigeria’s Debt and Economic Growth Record

Given the importance of Nigeria’s economy to the prosperity of the wider African continent, it is prudent to take a closer look at the nation’s debt management plan with the aim of proposing solutions to make better debt management policies. This analysis will be a microcosm of the effects of debt management on emerging economies in Africa because Nigeria is among many countries that have revamped their physical planning strategies to address local and domestic economic challenges through debt management (Databod, 2017, p. 1). Given that the oil-producing giant is among the strongest economies in Africa, there is potential that it could be a beacon of prudent fiscal management on the continent after improving its economic planning. This is why many African nations look up to Nigeria as a leader in many areas of social, economic, and political development. Consequently, this case study will be instrumental in understanding debt management strategies in Africa and identifying its successes or failures with the aim of developing proposals for improvement.

This paper is structured into five main sections. The first one is the introduction chapter, which highlights the background to the research topic and its importance to the management of public debt in Africa and, by extension, low-income countries. The second section provides descriptions of key terms, concepts, and descriptions that are relevant to the study. Its goal is to highlight the nature of the extant literature and the research gap justifying the present study. In the third part of this paper, the researcher will highlight the methods chosen by the researcher to undertake data analysis. The fourth section of the study will highlight its findings and their contribution to answering the research questions. In this part of the study, the main findings will be critically evaluated, relative to how Nigeria manages or uses its debt to spur economic growth and development. The last section of the study is the conclusion part, which summarizes the main findings of the investigation, its limitations, and policy implications.

Overall, the main objectives of this study are: (i) to determine Nigeria’s safe debt limit (ii) to find out why debt financing has not positively impacted sustainable economic growth in Nigeria and (iii) to identify effective strategies for managing Nigeria’s present and future debt. Based on these objectives, the researcher will be intending to answer three research questions: (a) what is the appropriate extent or nature of debts that can help Nigeria avoid unsustainable debt? (b) Why has debt financing not impacted sustainable economic growth in Nigeria? and (c) What debt strategies will be effective to manage Nigeria’s present and future debt obligations? From these questions, three hypotheses are derived: (H1) Nigeria can avoid unsustainable debt by maintaining levels that are lower than 60% of GDP, (H2) Debt financing has not positively affected sustainable economic growth in Nigeria because of inefficient debt management practices, and (H3) improvements in Nigeria’s cash flow management will help enhance the country’s debt management record.

Definitions of Debt Management, Economic Sustainability, and Fiscal Management

The concepts of debt management, economic sustainability, and fiscal management are central to understanding the effects of sovereign debts on a country’s economic growth. More importantly, they are pivotal in evaluating the economic sustainability of debt in the emerging markets context. Key issues that will be explored in this section include the justification for taking loans, theoretical underpinnings of prudent debt management, and the experiences of other countries with debt. The aim of undertaking this review is to understand how the current research on debt management in emerging economies is positioned within the greater body of literature that has explored the effects of debt growth on the economic sustainability of nations.

Debt Management Background, Concepts, and Paradigm

How Countries Manage Debt: Empirical Evidence

Debt is a financial instrument at the disposal of a country, which allows it to pay a principal or interest sum of money obtained in the future. Countries often accrue debt from different sources, including their own financial institutions, commercial banks, other nations, and global financial institutions, such as the World Bank (International Monetary Fund African Department, 2021, p. 1). In one study, the effect of debt was investigated by analyzing its impact on the economic freedom of the Jordanian-banking sector and those of other countries from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and using the Stochastic Frontier Approach (SFA) to control for country-specific variables, it was established that debt increased country risk and reduced economic freedom (Al-Gasaymeh, 2020, p. 1). By analyzing data from 90 banks in Jordan and the wider GCC region, the study also pointed out that poor debt management reduce the economic freedom of the financial institutions and increases their transaction costs (Al-Gasaymeh, 2020, p. 1). Therefore, effective debt management was considered an important attribute in improving the capability and capacity of financial institutions to compete with their peers and create a robust banking system.

Definitions of debt management stem from a broader understanding of financial planning based on the need to balance the total amount of money owed to creditors by state governments, federal governments, and their respective agencies (Hakura, 2020, p. 1). Using the debt dynamics equation, researchers have affirmed the impact of these different types of debt on economic performance by highlighting its importance in evaluating debt sustainability in two equations (Chandia et al., 2019, p. 25). The first one is the debt dynamics equation model for the overall debt owed by a country and the second one is for external debt sustainability management (p. 25). This definition of public debt not only encompasses money owed to creditors by the central government but also its financial and nonfinancial corporations. The same definition of public debt also encompasses debts covered by governmental agencies that are not held by public agencies and corporations but that the government has an obligation to cover (International Monetary Fund African Department, 2021, p. 4). External debt, which is held by nonresidents of a country, is also covered under this classification. Therefore, to understand a country’s public debt risk, it is vital to review all factors that could influence public finances.

On the contrary, adopting a narrow definition of public debt could lead to sudden increases in debt positions and a weakening of a country’s credit rating because several intertwined components of debt have to be taken into account when computing a nation’s financial obligations. For example, if a government or state agency defaults on its debt, the financial responsibility of the default falls on the central bank because it is publicly guaranteed (Hakura, 2020, p. 1). When this happens, it leads to the weakening of a country’s debt position and currency, as seen through an Indian-based study, which evaluated the effects of debt on manufacturing firms traded in the BSE 200 Index between 2009 and 2016 (Pandey & Sahu, 2019, p. 267). The investigation was designed to understand the relationship between debt financing, agency costs, and corporate performance. Using panel data estimations, the findings revealed that debt was detrimental to corporate performance (p. 267). However, it shared a positive correlation with agency cost, meaning that high debt burdens often lead to increases in agency costs (p. 267). Therefore, the negative effect of debt on corporate performance is affirmed through this empirical investigation and the high agency cost highlighted above is linked to high debt levels.

Economic Sustainability of Debt: Empirical Evidence

In the context of this analysis, the sustainability of an economy refers to how well it can be able to meet its debt obligations. In one Bangladesh study aimed at evaluating the economic feasibility of the country’s debt management policy, researchers conducted simulation exercises on economic data and reported that the economic sustainability of debt was achieved when the country had high economic growth rates (Bhattacharya & Ashraf, 2018, p. 137). Using the debt-stabilizing primary balance approach (DPSBA) to analyze economic data for the period 2017 -2026, the researchers established that the economic sustainability of debt was only achieved when the rate of economic growth was high enough to cover the real interest rates attributed to its servicing (p. 138). This cash flow model was deemed the best in evaluating the economic sustainability of debt but the analysis was focused on Bangladesh, where researchers pointed out that it will continue to struggle to realize debt sustainability because of the tradeoff between debt and investment (p. 139). In other words, Bangladesh was diverting most of its resources towards debt repayments at the expense of its investment objectives.

Based on the above statement, governments strive to adopt prudent debt management policies to manage their financial and debt commitments. More importantly, they strive to promote growth and stability by taking debt without negatively affecting the existing socioeconomic balance in the countries. If incorrectly done, unsustainable debt is likely to cause financial distress in an economy, thereby leading to the creation of extraneous circumstances that may lead to restructuring plans or the forfeiture of assets guaranteeing debts. The link between the economic sustainability of debt and its trade-off with investment returns that was mentioned in Bangladesh was also mirrored in a South African-based study (Saungweme & Odhiambo, 2021, p. 132). Using data gathered between 1970 and 2017 and analyzing it using the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL), it was established that poor debt management policies affected investment returns both in the short-term and long-term (Saungweme & Odhiambo, 2021, p. 132). Therefore, the relationship between aggregated poor debt management and Return on Investments (ROI) was statistically significant and negative at the same time (Aybarç, 2019, p. 1). Nonetheless, the results also showed that effective management of domestic debt had a statistically significant and positive relationship with economic growth, only in the short-term (Saungweme & Odhiambo, 2021, p. 132). Therefore, the findings highlighted in the investigation highlighted the need for effective debt management and the importance of redirecting resources to high growth and return sectors of the economy.

Fiscal Management as a Function of Debt Management: Empirical Evidence

Governments use multiple tools to control, direct, or plan resource use for purposes of promoting economic growth and meeting debt obligations. Fiscal management practices are part of such tools because they are macroeconomic management instruments that are relevant to debt management. From this statement, it is implied that improved governance could lead to a decline in budget deficits, thereby improving a country’s strength to service its debt. In one study designed to understand the dynamic relationship between fiscal planning and debt management, data relating to 12 West African countries were analyzed using the Pooled Mean Group and Mean Group estimator technique and a positive relationship between fiscal performance and deficit management was established (Fagbemi, 2019, p. 97). The empirical data used to come up with the findings related to the 1984 to 2016 period and the researchers argued that the inculcation of democratic values in governance had the highest potential of instilling fiscal discipline in debt management (p. 97). Therefore, the proportion of public debt could have a direct impact on the quality of fiscal management practices adopted by governments worldwide.

In a different study, the importance of fiscal planning was highlighted by estimating the impact that adjustments to macroeconomic policies would have on the economic growth of Pakistan (Hussein et al., 2021, p. 1). The investigation assessed the impact that spending and tax-based policies would have on the economic growth of the nation using the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) to analyze data (p. 1). The findings revealed that spending-based adjustments had a positive impact on economic growth levels, while tax-based adjustment measures had a negative impact on economic growth in the end. They were deduced by using the granger causality test and included looped feedback from the economic activities of Pakistan’s economy to inform its fiscal management policies (p. 1). Based on these findings, the main point that emerges from the investigation is the effective use of spending-based fiscal management policies to promote economic growth. Through this economic growth, government can better get the finances needed to service their debts. Therefore, fiscal management planning is an important part of debt management.

Although various economic indicators, such as debt to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratio, are used to evaluate debt management performance, citizen awareness, and their understanding of debt management could also play a significant role in instilling fiscal and monetary discipline in debt management. This is especially true in emerging economies, which are taking high levels of debt without significant citizen participation (International Monetary Fund African Department, 2021, p. 15).

Effects of Debt on Economies: Theoretical Evidence

The effects of debts on economies are underpinned by economic theories that have analyzed their impact on firms and national growth. Four main schools of thought explain debt management practices in economics. The first one is the classical theory of economics, which emphasizes the importance of countries to manage their fiscal and monetary issues in the way households do (Theory of public debt, 2019, p. 3). This approach to managing public resources stems from a largely pessimistic view of society, which deems government expenditure as wasteful and lacking the fiscal discipline required to manage such resources prudently (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2015, p. 1). Proponents of this school of thought hold this cynical view about state intervention in the management of economic affairs because they believe that private interests are better custodians of financial resources compared to the government (Theory of public debt, 2019, p. 5). This ideology stems from the understanding that public debt and expenditures are wasteful and unproductive.

The second theoretical foundation for understanding the impact of debt on economies is characterized by proponents of the classical view of economics, who caution against state borrowing by arguing that it eventually leads to bankruptcy due to the lack of strong accountability standards (Abbas & Rogoff, 2019, p. 6). Classical theorists, like Adam Smith, paint a far grimmer picture of public debt and state borrowing by suggesting that it reduces accountability of governments to their citizens by creating a new channel of resource pilferage – debt, as opposed to taxes, which is more difficult to misuse (Theory of public debt, 2019, p. 8). The classical view of economics is often matched with the irresponsibility of governments in sovereign debt management, as has been seen in the case where nations wage meaningless wars against enemies (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2015, p. 1). The counter argument presented in this debate is that government would be hesitant to enter into wars or sustain them for long periods if they were financing such ventures purely with state taxes. Therefore, the classical economist view of public debt is overly pessimistic about the role of the state in initiating economic reform among nations using debt.

The third view of public debt management is based on the Ricardian basis of economics, which highlights the irrelevance of fiscal policies in correcting balance of payments, especially when there are budget deficits. Researchers have supported this philosophy by emphasizing the importance of meeting debt-servicing requirements without paying much attention to the interest rate regime in place (Khurram et al., 2019, p. 23). This view is partly explained in studies that have highlighted the importance of maintaining budget surpluses as a basis for prudent debt management (Abbas & Rogoff, 2019, p. 34). An example is given of the US government between 1916 and 1995 when it enjoyed a budget surplus, which meant that the country could effectively service its debt (p. 37). Studies that have investigated the effects of government expenditure on economic output more intricately suggest that debt investments spur growth but taxes have the opposite effect (Chandia et al., 2019, p. 25). Overall, Ricardian economics suggest that debt should only be taken when a country has adequate surplus cash to pay for its repayments.

The fourth school of thought explaining debt management in economics is based on the Keynesian school of economics, which outlines a framework for analyzing economic growth through “deficit spending.” Deficit spending often arises when governments have expenses that surpass their revenue collections (Theory of public debt, 2019, p. 5). Therefore, the Keynesian school of economics supports a government’s quest to seek financial resources, through loans, and use its purchasing power to spur economic growth by creating demand for goods and services in the economy when making expenses on it. The Keynesian theory of public debt management has gained credence in the 21st century as economists view the process of managing national budgets as akin to those associated with debt management in the corporate arena (p. 7). In this arrangement, the state is viewed as a corporation and, like companies use debt to expand their markets or improve their production processes, they are allowed to take debt to spur their economic activities (p. 1). This modern view of economics departs from the classical view of debt management, which is suspicious about the role of the state in spurring economic activities. The Keynesian school of thought stems from economists who have adopted a liberal view of public debt management, by suggesting that it does not necessarily have to be wasteful.

Two scholars, Miller and Modgliani, have proposed additional theories on debt management by suggesting that a country’s economic growth potential should not be affected by capital restructuring through debt management (Atsede & Brychan, 2017, p. 90). Their arguments are predicated on the assumption that, in a perfect market setting, debt should not affect the economic value of a nation. Similarly, the financing arrangements employed by a country to spur economic investments should not have an effect on its overall value (Global Economy, 2020, p. 1). Closely linked to the views of Miller and Modgliani is the tradeoff theory, which suggests that countries are prone to exploiting low costs of borrowing without linking it with a commensurate increase in financial risk that would cover debt and capital repayment obligations (Aybarç, 2019, p. 1). Therefore, this theory encourages governments to strike a balance between the economic costs of borrowing and the associated liabilities and costs associated with interest and financial payments. Under these conditions, the tradeoff theory encourages firms to use debt when interest rate payments are low and avoid it when the same are high or unsustainable (Atsede & Brychan, 2017, p. 91). The relationship between debt and interest rates draws comparisons with the concept of economic sustainability of debt identified in this paper because debts that cannot be serviced effectively are deemed economically unsustainable, while those that can be effectively serviced using a country’s positive cash flow are sustainable.

The political business cycle theory has also been proposed to explain public debt management in developing countries. It advances a political explanation to public debt management by arguing that politicians often increase their demand for loans when election nears (Theory of public debt, 2019, p. 3). The justification for doing so is embedded in the belief that governments use debt to initiate development projects for re-election, as opposed to catalyzing economic growth. To support this view, some researchers opine that such practices are often initiated by corrupt government officials to manipulate voters through debt-initiated development, which has a low short-term cost, as opposed to tax-funded development, which could disgruntle voters due to high taxes (Khurram et al., 2019, p. 22). Therefore, much of debt-initiated development are taken to fulfill short-term goals, but the ramifications on the economy are widespread and may last a long time.

Benefits of Debt to Host Countries

The link between debt and economic growth has been discussed in various forums and it is established that it could have a positive and negative impact, depending on how it is managed or used (Onyemelukwe, 2016, p. 1). For instance, debt could have a positive or negative effect on an economy, depending on how state officers negotiate for its terms and its use in financing investment projects. Its positive effects emerge when governments use loans prudently to support economic growth, such as through the construction of industries, roads, and other income generating activities (Atsede & Brychan, 2017, p. 7). Alternatively, debt could have a negative effect on economies if authorities misuse or fail to direct it towards funding activities that would add value to the economy. Therefore, countries take loans to achieve varied goals, including promoting the realization of long-term economic objectives, stabilization of macroeconomic conditions, and asset management, as outlined below.

Promoting Long-term Economic Growth: One of the major benefits of debt is the promotion of long-term economic growth in a country. This objective is achievable through sustained investments in human and physical capital for spurring economic growth (Pham, 2017, p. 5). Economists have hailed this positive contribution of debt to economic growth by linking it with gains in socioeconomic development, such as poverty reduction (Kose et al., 2020, p. 6). The World Bank makes the case for public debt in developing countries by arguing that it is important in sustaining significant levels of economic growth that would yield positive socioeconomic outcomes (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2015, p. 1). For example, recent forecasts show that most developing nations may experience a 0.5% reduction in economic activities between the years 2018 and 2027, if they do not get debt support (Kose et al., 2020, p. 6). Compared to the sustained economic growth of 5.7% reported between 1998 and 2017, the case for increased public spending in developing countries is made to achieve such levels of economic growth in future (p. 8). Therefore, the economic growth of developing nations is tightly knitted in the need for prudent public debt management and maintenance. Particularly, Africa is seen to be in need of debt to provide resources needed to meet its financing gaps (International Monetary Fund African Department, 2021, p. 1). These resources are estimated to cost African governments more than $93 billion annually and the continent is expected to get financing through debt to meet this financial cost, without which it would be unable to compete with other regional markets of the world (p. 38). Therefore, in this context of analysis, debt is considered an essential tool for promoting long-term economic growth.

Stabilization of Macroeconomic Fluctuations: Governments often experience macroeconomic fluctuations due to changes in their fiscal and monetary environments (Global Economy, 2020, p. 1). Consequently, there is a need to balance these influences using debt management instruments. Short-term debt often plays a key role in balancing these macroeconomic indicators through increased government spending or tax cuts. However, to understand how debt can stabilize macroeconomic fluctuations in an economy, it is important to understand the multiplier effect of government spending. Depending on circumstances, the multiplier effect often works within a range of 1.1-dollar decline to a 3.8-dollar increase for increased government spending or tax cuts occasioned by the implementation of debt-funded projects (Kose et al., 2020, p. 6). Research also shows that the multiplier effect of debt often occurs during periods of economic suppression, as opposed to economic growth (International Monetary Fund African Department, 2021, p. 35). Particularly, during recessions, the multiplier effect could be between three and four times the investment made in an economy from debt or other sources of funds (Kose et al., 2020, p. 7). This effect is more impactful in developed countries as opposed to emerging economies and is dependent on whether a country is in a crisis, or not; or whether it has flexible or fixed exchange rates (Abbas & Rogoff, 2019, p. 30). Debt management is a reliable tool for managing these macroeconomic influences.

Providing Safe Assets: Sovereign debt is regarded a safe asset because it is publicly guaranteed, implying a minimal risk of default (Al-Gasaymeh, 2020, p. 1). This situation is unlike private debt, which could easily be defaulted. Therefore, sovereign debt provides a safe class of asset for people who may be looking to find new investment channels for making a profit. This type of asset is notably important in events of economic uncertainty when the potential for risk aversion is high within the economy (Theory of public debt, 2019, p. 3). Sovereign debt is often desirable in such circumstances because constraints on private borrowing often increase during these periods (Kose et al., 2020, p. 7). This characteristic of the debt environment is mostly relevant in developing economies, which are vulnerable to economic uncertainties and the effects of weak financial institutions on the overall record of governance. Given that sovereign debt is more attractive to investors during periods of economic uncertainty, it creates a channel for making safe investments in the economy.

Cost of Debt to Host Countries

The cost of debt, if not managed well, could have negative implications on an economy. Indeed, the negative effects of debt materialize when countries take more loans than they can service. In this regard, they strain their fiscal management capabilities because hefty loan payments mean that current revenues may be unsustainable to meet debt obligations (Aybarç, 2019, p. 1). Consequently, there is a need for prudent debt management by striking a balance between the cost of debt and the payoff. This can only be done by servicing debt at reasonable costs, regardless of the economic circumstances involved (Hakura, 2020, p. 1). However, few low-income countries have the right tools, skills, institutional maturity, or legal frameworks to actualize this goal (United Nations, 2020, p. 56). In the context of this review, retrogressive economic growth rates, increased vulnerability to economic crises, and high interest rates emerge as the main areas of concern in debt management. They are presented as the main costs of debt to host nations.

Interest Rates: Debts are ideally supposed to finance economic projects to spur investments and expand growth. However, like other factors of production, they come with interest payments, which refer to the cost of capital borrowed. Indeed, as corporations do, governments compete with private entities for capital in the financial markets and pay interest as a result (Theory of public debt, 2019, p. 3). These interest rates refer to the amount of money they would pay to access debt and they are affected by extraneous factors, among them being changes in GDP, currency fluctuations, and government policies (International Monetary Fund African Department, 2021, p. 15). Discussions about the implications of debt on economies, through discussions on interest rate regimes, have also shown that there is a need to strike a balance between interest rates and the nominal GDPs of countries.

In this context of analysis, if interest rates associated with debt repayments are below the nominal GDP, the true cost of debt will decline over time as the multiplier effect starts (Bhattacharya & Ashraf, 2018, p. 139). In other words, the rate of return from the economic activities created by the multiplier effect will be sufficient to cover all the debt repayment obligations associated with a loan or government financial activity. Therefore, to have a holistic understanding of the impact of debt on interest rate repayments, it is not enough to only look at the rate of debt repayment but also the constraints caused by the accumulation of new debt (Raudino, 2016, p. 105). This approach to debt management is adopted to balance the positive and negative effects of debt on an economy. A country’s debt stock is likely to increase when the interest rates caused by the accumulation of new debt causes more financial constraints on an economy than it can handle by simply focusing on current debts.

Vulnerability to Economic Crises: Highly indebted countries are more vulnerable to the upheavals of economic cycles and boom more than those that have low, or sustainable, levels of debt (Debt Management Office Nigeria, 2017, p. 3). This situation creates vulnerability in the management of a country’s fiscal management policy framework because debt-to-GDP ratio is the single-most common determinant for assessing economic vulnerability to crises (Kose et al., 2020, p. 6). This vulnerability could manifest in different ways, such as currency fluctuations, which could occur when governments rapidly accumulate debt. The outcome may be linked with low investor confidence, which could undermine a government’s ability to meet its debt obligations (International Monetary Fund African Department, 2021, p. 1). Another way that debt increases vulnerability to economic crises is through its effects on the prices of goods and services by causing a deflationary effect on the economy (p. 15). Given that private sector players use their own resources to buy bonds, the general prices of goods and services declines when these resources are withdrawn from the market, thereby creating the deflationary pressure described above (Aybarç, 2019, p. 6). However, given some time, the government will start using the borrowed funds to purchase goods and services, thereby creating a new inflationary push, which will increase the price of goods and services. Therefore, in the context of this study, public debt causes significant variations in the prices of goods and services, thereby leaving economies vulnerable to economic and market shocks.

Risks to Economic Growth: Mismanaged national debts also pose a risk to the economic growth of countries. However, this outcome is implicit because some scholars hold a contrary view. For example, economists, such as Kenneth Rogoff, have argued that debt is only favorable to economic growth when it is maintained at levels below 60% of GDP (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2015, p. 1). At the same time, it is argued that subsequent increases in this percentage is likely to decrease economic growth from 6% to about 1.4%, thereby drawing a relationship between high debt levels and low levels of economic growth (p. 1). Relative to this statement, the relationship between high levels of debt and low economic growth rates is attributed to countries, which have debt levels that are about 90% of their GDPs (p. 1). A different group of researchers believes that the relationship between high debt levels and low economic growth is weak (Aybarç, 2019, p. 7). Adding to this debate are economists, such as Paul Krugman, who opine that low levels of economic growth lead to high debt levels, thereby insinuating that low economic growth rates are not caused by high debt levels (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2015, p. 5). Regardless of how one looks at these arguments, debt can cause economic crises if poorly managed because of its risks to economic growth.

International Experience with Fiscal Management

The need for prudent fiscal management is grounded in the importance of achieving debt sustainability for low-income countries. Supported by procedural rules, prudent fiscal debt management helps in guiding budgetary processes and ensures that state organs absorb their funds within stipulated budgetary allocation guidelines (International Monetary Fund African Department, 2021, p. 4). This process ensures that there is a healthy balance of payment between what a country gets as revenue and what it uses to pay off recurrent expenses, finance development projects, and meet debt obligations (Chandia et al., p. 25). Indeed, most countries that have adopted fiscal rules to manage their balance of payments have put permanent constraints on managing fiscal aggregates, such as expenditure and amount of money the government can borrow or allocate to recurring and non-recurring expenses.

There is no optimal plan for designing or implementing fiscal management policies because governments have had varying experiences implementing these policies based on their unique fiscal objectives and strengths of their financial or state institutions. Therefore, governments have unique experiences managing their fiscal issues. Consequently, developing countries register unique challenges affecting their balance of payments compared to their developed counterparts (Atsede & Brychan, 2017, p. 1). While it is important to understand the fiscal management policies adopted by a government when investigating its balance of payments, it is similarly essential to acknowledge that it is only until the 1980s when governments around the world started to operate under known fiscal management rules (Cevik, 2019, p. 4). Before that time, only a few countries operated under such conditions. Additionally, it is suggested that most of the differences in fiscal management polices among countries vary in the manner they manage debt, budgets, expenditure, and revenue streams (Al-Gasaymeh, 2020, p. 1). The biggest variations in fiscal policies arise in the manner countries manage their budgets (Onyemelukwe, 2016, p. 1). These insights highlight the need to understand how different countries have experienced and managed debt.

Comparison of Debt Management by Countries

For purposes of this investigation, debt management practices in North Korea, Argentina, the United States, and Russia will be explored to evaluate the experiences of other countries with loans and to estimate their impact on economies.

Debt Management in North Korea

North Korea is a centrally controlled economy with a murky history of debt repayment. Its trading partners have accused it of not meeting its debt obligations, while others have opted to write off or restructure some of its debts (Ward & Silberstein , 2018, p. 1). Part of the problem of North Korea’s fiscal management policy is the failure to respect international laws of finance. This issue has led to low levels of confidence by international partners in the government’s ability to abide by terms and conditions regulating debt management (p. 1). This is why poor fiscal management of the country’s financial resources led to the default of debt in 1987. The problem was traced to the mismanagement of financial resources in post-war North Korea and the redirection of funds to military spending, as opposed to the economic revival of the state (p. 3). The lack of accountability in the management of public finances also led to a deterioration of international relations and a breakdown of the diplomatic arrangements between nations that underpinned their debt management plans (p. 4). These issues forced international organizations to list North Korea among countries that have poor debt management practices.

Debt Management in the United States (US)

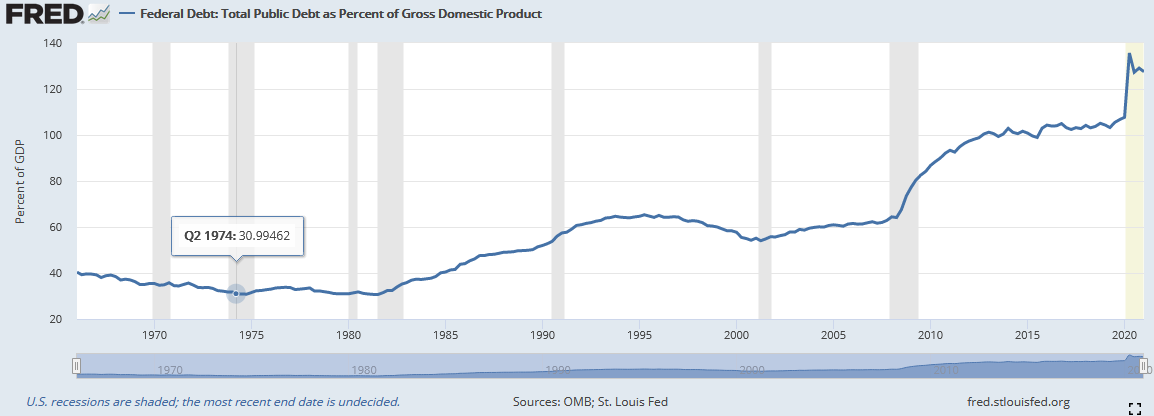

A review of the US debt management plan is important to this study because America is among the largest holders of external debt in the world (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2021, p. 1). By aggregating its intergovernmental holdings and national debt, the world’s biggest economy has a collective federal debt of about $27 trillion (p. 3). Subject to these statistics, as of 2020, the US debt to GDP ratio was estimated to be about 98% (p. 4). Current proposals to inject more stimulus money in the economy to rebuild infrastructure and support businesses that were affected by the Coronavirus pandemic are expected to push the percentage of debt-to-GDP to 100% (p. 5). Figure 2.1 below presents a breakdown of the total value of US debt as a percentage of GDP between 1970 and 2020.

Stemming from the increase in debt to GDP ratio for the US government highlighted above, observers believe the American government practices prudent fiscal debt management policies that are on track to increase the value of investments derived from debt in the long-term (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2021, p. 3). Furthermore, good political goodwill and America’s positive standing in the community of nations still encourage many investors to have a favorable view of US debt.

Debt Management in Russia

Similar to North Korea, Russia has also had a poor history of debt management. Prior to the year 1998, the country’s debt burden was not of critical importance to the global economy, especially given that the country was one of the world’s major superpowers (Santos, 2020, p. 1). Therefore, it was assumed to have the capability to meet its debt obligations. However, the government’s failure to meet growing short-term debt requirements forced it to default on payments in the 1990s (p. 3). As one of the world’s strongest nations, the default of Russia’s public debt in 1998 shocked the global market (p. 3). It happened because the country was vulnerable to price fluctuations occasioned by the sale of commodities, which supported a significant part of the country’s economic blueprint.

Against this backdrop, the lack of political goodwill among creditors and the Russian government’s inability to account for its assets and resources saw most of the debt written off. Others are still pending and unpaid because debtors have no powers to enforce the agreements (p. 2). The Russian debt management problem is unique from the other cases sampled in this review because its debt default was not exclusively caused by poor debt management policies or practices, but by political events occurring at the time. Indeed, its role in the Soviet era economic reorganization forced it to assume responsibility for most of the debt that was left after the collapse of the union (p. 5). The government underestimated the burden of this debt on its finances, thereby occasioning the default.

Debt Management in Argentina

The government of Argentina defaulted on its debt in the year 2002, leading to a loss of investor confidence and capital flight from the economy (Perez & Dube, 2020, p. 3). The problem was caused by an economic recession in the 1990s, which followed a period of economic boom the previous decade (p. 3). Since then, the country has been unable to stabilize its fiscal management plans because it has defaulted on its debt for the ninth time in a row (p. 1). Ravaged by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, runaway inflation, job losses, and currency squeezes have further seen Argentina unable to meet its debt obligations with the recent case being its inability to pay $500 million in interest payments to a lender (p. 3). In the meantime, part of the debt currently owed to bondholders is more than $65 billion (Perez & Dube, 2020, p. 7). The current case of default is a product of past restructuring efforts – meaning that the government has been unable to meet basic financial and debt obligations. There is little faith that the country will be able to meet these obligations, thereby leaving creditors with debt restructuring as the only hope for getting paid.

State of Debt in Emerging Economies

Developed countries have significantly lower levels of debt vulnerabilities compared to those in emerging markets due to the strength of their macroeconomic institutions. Averagely, these countries have a debt to GDP ratio of 30%, while most developing countries post figures of 60% or higher (Abbas & Rogoff, 2019, p. 34). Within the emerging markets context, countries that have taken significant debt are located in Latin America and East Asia. These nations took significant levels of debt from the 1920s to the 1930s period as well as the 1970s to 1980s period (p. 33). For example, between 1920 and 1930, Argentina took loans that increased its debt percentage to GDP ratio from 56% to 118% (p. 34). Similarly, during the same period, Brazil’s national debt as a percentage of GDP rose from 23% to 52% (p. 35). These are a few examples of Latin American countries that experienced economic vulnerabilities due to their rising debt burdens.

The debt to GDP ratio in emerging markets significantly declined from the highs set in 1930s to a significantly lower level in the 2000s due to debt restructuring and changes to GDP that occurred during the period. Particularly, interest suspension and payment amortization were adopted among low-income countries to avoid debt distress (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2021, p. 3). Particularly, Eastern European and Latin American countries were affected by this trend. Their problems were compounded by weak commodity prices and restrictions on international trade. Consequently, it was difficult for debtors to earn money from external debt, thereby forcing some of them to suspend their budgets and unilaterally stop debt-service payments (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2021, p. 5). Agreements made on restructuring of debts were agreed among bondholders after the Second World War, thereby creating a significant period of foreign debt payment among low-income countries (Abbas & Rogoff, 2019, p. 34). These events shaped the effects of debt on major emerging economies of the world.

In the 20th century, the effects of debt on emerging economies became more apparent. The anchor debt level has been set at 45% and the potential output debt level has been between 3.6% and 5.2% (Cevik, 2019, p. 4). Domestic borrowing and intergovernmental debt shifted this debt burden again, culminating in a crisis in the 1980s that was characterized by the same factors observed in the 1920s-1930s period – low commodity prices and high interest rates (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2021, p. 5). At the same time, the Brady plan of 1989 changed the debt management practices of many low-income countries because it allowed debts to be restructured and securitized (Abbas & Rogoff, 2019, p. 31). This strategy gave the bond market the liquidity it needed to jumpstart bond issuance again. The Brady Plan was introduced after seven years of economic upheaval caused by poor debt management in major world economies (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2021, p. 1). During this time, rich countries were unwilling to reduce the principal amounts of the debts owed by low-income countries (Fagbemi, 2019, p. 1). Their hesitancy was pegged on the desire to see commercial banks develop sufficient capital during this period to accommodate debt-restructuring processes. Therefore, there has been an exchange of debt management practices and experiences among different countries. Evidently, low-income countries are affected by different macroeconomic dynamics that shape how they design their debt management plans.

Summary

The findings highlighted in this chapter have explored the relationship between economic growth and loans by first understanding relevant concepts involved in debt management and secondly by evaluating the experiences of different countries in managing this loan instrument. Of critical importance to the current investigation are the lack of empirical works of literature on Nigeria, which is Africa’s biggest economy. Furthermore, there is limited understanding of the impact of recent events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, on the country’s debt management practices. This gap in the literature provides the justification for the present investigation.

Comparison of Nigeria’s Debt with its GDP

The relationship between the effects of debt burden on sustainable growth is investigated in this section of the thesis as a case study of Nigeria’s debt management policy, vis-à-vis its economic objectives. Key pieces of information that will be explained in this section of the study include a comparison of the debt effects of Nigeria’s debt on its GDP growth.

Sources of Data

The researcher obtained data relating to Nigeria’s debt management record and economic growth performance from the World Bank Database. Data was obtained from this institution because it is one of the largest international organizations providing debt relief to low-income nations, including Nigeria (World Bank, 2021, p. 1). The international body also manages a digital library of international data relating to the debt management records of several African countries, including Nigeria (p. 1). The information available was published within the past 30 years with a focus on the 2009-2019 period to make it more relevant to the present times and the current context of the analysis.

This research study also included supplementary information from secondary research data to answer the research questions. This type of analysis involves a review of research materials, including books, journals, and credible websites. Published data was sourced form credible journal databases, including Sage Journals, “Emerald Insight,” and Springer. Books were sourced from Google Books and Google Scholar. Government reports and institutional publications regarding the fiscal management of national debts were integrated in the research study to provide a contextualized understanding of national debt policies and how other nations have used their debt prudently, or wasted it for varied reasons. The need to obtain updated data was important to the researcher and this is why the books and journals used in the study were published between 2016 and 2021. To improve the credibility of information obtained from the search process, the journals articles collected and reviewed in the analysis were also peer-reviewed. Government reports also formed a significant part of the body of literature that was used to complete the current investigation. Additionally, information from Nigerian authorities was relied on to understand the country’s debt riskiness levels.

The main dataset used in the study and that was obtained from the World Bank was extracted from historical records relating to Nigeria’s debt management records because the institution undertakes annual evaluations of the country’s macroeconomic indicators (World Bank, 2021). Therefore, it was possible to get 10 and 20-year historical data about Nigeria’s debt and GDP to make inferences about the research issues. Therefore, the data obtained from the intergovernmental agency were instrumental in providing an objective assessment of Nigeria’s debt sustainability levels. Broadly, the analysis was undertaken within a macroeconomic context and included macroeconomic indicators present under specific conditions and assumptions underpinning the economic health of the country.

The data was available in form of a time-series analysis and covered the debt-related statistics for Nigeria between 1960 and 2020. However for purposes of this review, the researcher only used data relating to the period between 2009 and 2019 because this is the time Nigeria started taking significant levels of debt to spur economic growth (Debt Management Office Nigeria, 2017, p. 1). Overall, data from the World Bank was used because it is a reputable global institution that manages large volumes of data relating to the economic performance of nations, relative to their debt management practices.

Topic Specification Criterion and Variables

There are three types of topics in bachelor theses: theoretically deductive topics, empirically inductive topics, and conceptual topics. The theoretically deductive topic is not suited for the present study because it derives hypotheses from a theory or a set of theories. Furthermore, the current study does not rely on a theoretical framework to undertake the investigation. Therefore, it is mismatched with the present direction of the investigation. The selected topic is also not a conceptual one because it is focused on the development of models to solve managerial problems (Hennink et al., 2020, p. 204). It does not seek to develop a model to solve a managerial problem; instead, it is focused on understanding the relationship effects of debt burden on sustainable economic growth. This direction of investigation makes it an empirically inductive topic because the researcher will conduct statistical research to observe the above-mentioned phenomenon.

Nigeria was selected as a case study because it is one of the leading economies in Sub-Saharan Africa. Additionally, as one of the most populous nations on the continent, the West African nation has attracted international attention for being an example of how African governments design and implement their fiscal management policies (Debt Management Office Nigeria, 2017, p. 1). Its improved continental visibility stems from the government’s commitment of to improve transparency in economic governance and fiscal management (Zhu et al., 2018, p. 35). However, with this renewed commitment, Nigeria has continued to increase its debt over the years. The current public debt owed by the Federal Government of Nigeria and several of its states could be enough to create significant economic reforms in the country (International Monetary Fund African Department, 2021, p. 25). However, this change has not been fully realized due to factors that will be explained in subsequent sections of this paper.

At the same time, it is estimated that the country needs about $25 billion in investment annually for the next seven years to realize significant economic reforms or changes in the economy (Debt Management Office Nigeria, 2017, p. 35). In 2017, the Nigerian government introduced a fiscal policy law that stated all borrowing should be made for purposes of financing capital projects and human development programs (p. 36). Given that most debts accrued by the Nigerian government are concessional loans, approval is often sought from parliament before amortization commences (p. 5). The Fiscal Responsibility Act also stipulates that Nigeria’s debt should be sustainable and subject to limitations of spend (p. 1). Nonetheless, there is a difference between the negative and positive impacts of debt on the economy because the positive effects of debt have a lower magnitude compared to its negative effects. The current analysis on Nigeria’s debt management practices will provide an example of how African countries manage their debt. Similarly, improving Nigeria’s debt management practices would help other nations to adopt similar practices, thereby providing a model of governance for managing the relationship between debt and economic growth. Consequently, the Nigerian case study will be important in understanding how African governments are managing their fiscal and monetary obligations, relating to debt management.

Based on the above-mentioned statement, the current research is focused on proving whether the assumption that debt could spur economic investment is true, or not, in the case of Nigeria. As a classic example of an emerging economy in Africa, years of debt accumulation in Nigeria has provided many data for analyzing whether the financial instruments have served their intended purpose, or not (Debt Management Office Nigeria, 2017, p. 5). The current investigation is also an empirically derived topic because it relies on statistical tests to ascertain whether a hypothesis is true or not. In other words, this research design allows researchers to derive hypotheses from current empirical results (Mizik & Hanssens, 2018, p. 1). Therefore, the study is empirically inductive because the sustainability of economic growth based on its debt model is a hypothesis that was tested with statistics, which represents the economic reality of a nation.

Some of the policy proposals that will be developed in the investigation will be unique to Nigeria. Therefore, the country-specific nature of this study limits the generalizability of its findings because the debt constraints facing one nation are significantly different from those affecting others (Bhattacharya & Ashraf, 2018, p. 137). Stated differently, the nation-specific character of the current investigation has implications that stretch beyond the debt management practices of Nigeria because they also accentuate fiscal management challenges, relating to loan servicing, in emerging economies with limited financial resources (Chandia et al., 2019, p. 25). Therefore, country-specific differences play a key role in understanding how data is collected and formulated. For example, the constraints that the US government could face in paying off its debt could be different from another country because the US holds the world’s reserve currency. The Nigerian case also has such unique dynamics because the economy is energy-dependent and yet the largest in Africa.

In an emerging market context, the same differences are true for countries that are resource-rich and those that are not. For example, the debt dynamics facing a resource-rich nation, such as Saudi Arabia could be vastly different from those that affect a country that has a diversified economy, such as Japan or the Philippines (Pham, 2017, p. 1). In the African context, the same is true for Nigeria, which is a resource-rich country and, say, Ghana, or Kenya, which has a relatively diversified economy (Atsede & Brychan, 2017, p. 5). Furthermore, in the African context, some countries have heavily collaterized debt, which exposes them to more debt vulnerabilities compared to nations that do not have such types of debt.

In this investigation, discussions about the debt burden of the Nigerian government will be undertaken within specific time limitations. In other words, the investigation is limited within a 10-year period of analysis that starts from the year 2010 and ends in 2020. Therefore, debt management policies and practices that fall outside of this window of analysis will not be given weight in this review. In other words, references made to debt management practices that were outside the bounds of this period of analysis will be excluded to provide a contextual framework of the analysis and not to influence the assessment. Therefore, it should be noted that the current findings are limited to Nigeria’s debt environment within the 2010 and 2020 period.

Given that the present study is designed to understand the effects of debt burden on sustainable economic growth in Nigeria, the two main variables in the study were external debt and economic growth. External debt was measured using Nigeria’s External debt stocks, public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) (DOD, current US$), while economic growth was measured using the GDP growth (World Bank, 2021, p. 1). The relationship between the two variables was initially controlled for population increase and inflation. These two variables were included in the analysis because they can distort the people’s understanding of the relationship between economic growth and debt due to their effect on economic performance of nations (Bhattacharya & Ashraf, 2018, p. 138). For example, economic growth is likely to be undermined by a rise in population numbers because a surge in the population would cause an increase in the demand for goods and services. Similarly, the economic performance of Nigeria is affected by inflation because it may cause an increase in the prices of products, thereby leading to eroded economic gains. Additionally, the researcher controlled for three more variables, including labor, exports and capital flow as described below.

Capital Flow: Nigeria’s public debt is mostly sourced from international financial markets and institutions. Capital flow from external sources would have an impact on its economic performance (Onyemelukwe, 2016, p. 194). For example, an increase in remittance from diaspora workers could have a positive impact on the economy, especially if the capital is used for investments. Therefore, it was important to control for the effect of this variable in the current investigation.

Exports: A country’s exports are likely to affect its economic growth numbers. Nigeria’s main export is oil and a trade surplus in this product would likely have a positive impact on its economic growth. This variable has been mentioned in several economic reports involving a macroeconomic analysis of international economic data (World Bank, 2021, p. 1). Therefore, it is important to account for the impact that exports would have on a country’s economic growth numbers when evaluating the impact that a country’s debt level would have on its economic growth (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2015, p. 1). Given that Nigeria is largely an export-oriented economy; therefore, this variable was controlled in the analysis.

Labor: Human resource is one of the main factors of production. Indeed, people are at the center of many economic activities because they are involved in the production and consumption of goods and services. An increase in labor output would have a positive impact on the economic growth of a country, while a decrease in the same could cause a contraction of the economy as employers look for skilled workers to complete tasks (Onyemelukwe, 2016, p. 130). In this regard, labor was one of the control variables in the current investigation.

Model Description of GDP and Debt Trends in Nigeria

In this investigation, Nigeria emerges as a case study for understanding the relationship effects of debt burden on sustainable economic growth. The West African nation has relied on debt to meet its economic objectives for decades and since the 1990s, its loans have significantly increased to accommodate improved economic activities in the nation (Debt Management Office Nigeria, 2017, p. 5). Today, Nigeria’s public debt is estimated to be $57 billion, which represents a 174% increase in public debt in the last five years (World Bank, 2021, p. 1). Different local state jurisdictions, within Nigeria, have already exceeded their limits for borrowing with Lagos leading in surpassing its debt ceiling to account for about 30% of the country’s total national debt (International Monetary Fund African Department, 2021, p. 57). Other states have borrowed in excess of 200% of their national revenues. Osun and Cross River States have reported statistics that are more troublesome because their debts cover about 500% of their revenues (p. 58). These statistics show that Nigeria is heavily indebted both at domestic and national levels.

The data obtained above was analyzed using the Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software – version 24. This technique was used in the study because it can analyze large volumes of data in accurately and efficiently. This is why it has been hailed as an effective data analysis tool for social sciences. The information obtained from the World Bank database, highlighted above, was available in excel format. The researcher had to convert it to CSV format, which was the acceptable type of data for the SPSS analysis. Later, the researcher curated this data by recalibrating the scope of the analysis to the desired timeframe of analysis – 2009-2019. The information was later analyzed using the regression analysis (curve estimation option) and the findings used to test the hypotheses. A description of then model is highlighted in table 3.1 below.

Table 3.1: Model description

Using debt as the dependent variable, the model summary appears in table 3.2 as follows

Table 3.2: Model summary

A summary of the cases processed using the SPSS regression technique is also provided in table 3.3 below.

Table 3.3: Case processing summary

According to the findings highlighted above, 12 cases were included in the analysis representing the number of years that the data represented- from 2009 to 2019. The one excluded variable symbolized the nominal value of the variables, which did not contain numeric data. Overall, the researcher relied on published data from the World Bank, relating to Nigeria’s GDP growth and total external debts for the years 2009 to 2019 to develop this study. The SPSS technique was used to estimate the impact that the country’s debt has had on Nigeria’s economic growth and its findings used as the basis for testing the hypotheses.

Nigeria’s Debt Management Performance

Subject to how other nations have used debt to spur economic investments, this chapter delves deeper into the particulars of Nigeria’s public debt management policy with the view of understanding its priority areas and evaluating whether the current debt has helped to spur economic growth, or not. The findings of the regression analysis described above are presented below.

Relationship between Nigeria’s Debt and GDP Growth

As highlighted in this document, the two main variables investigated in this study were debt and GDP growth. The researcher conducted a regression analysis using SPSS version 24 to estimate the relationship between these variables. Table 4.1 below is a summary of the variables used to undertake the investigation.

Table 4.1: Variable processing summary

The number of positive or negative values referred in the table relate to the positive and negative rates of GDP growth reported due to changes in debt levels. Similarly, the zero value refers to a year of no economic growth in Nigeria.

The ANOVA findings, including the coefficients are described in Table 4.2 below

Table 4.2: ANOVA and Co-efficient findings

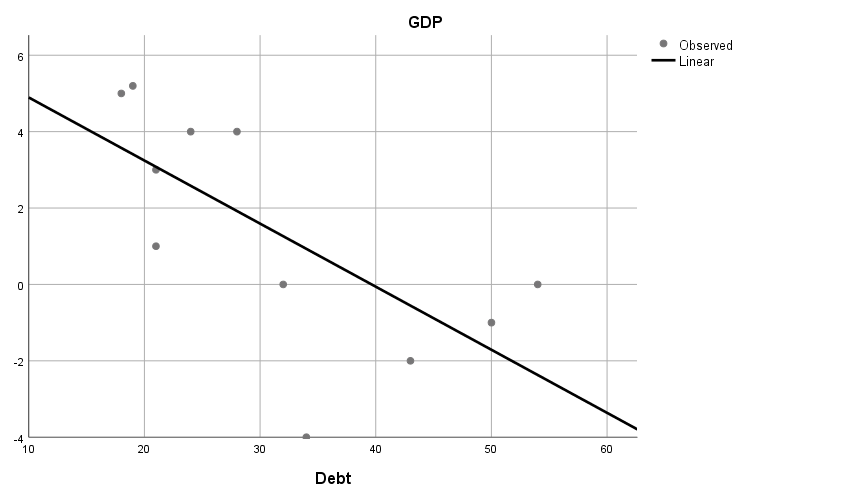

The scatter plot diagram highlighted in figure 4.1 below summarizes the findings because it shows that Nigeria’s economic growth has declined with an increase in debt levels.

According to the diagram, the Y-axis represents the rate of economic growth in Nigeria as a percentage, while the X-axis represents the total debt in billions of US dollars. Nigeria’s poor economic growth rate has been influenced by several factors, most of which stem from global shifts in oil prices (Trading Economics, 2020, p. 1). Figure 4.1 shows that Nigeria has been reporting an average GDP growth rate of between 4% and 6% throughout the 2009-2014 period. This improved rate of GDP growth was commensurate with the rising level of debt in the country. This trend was disrupted by a dip in oil prices in 2016, which led to significant declines in revenue and the lowest GDP growth rate in a decade. During this period, the country’s overall fiscal deficit was following the same pattern with lowest deficit reported in 2014, which represents the highest point of GDP growth. These statistics explain the disjointed relationship between debt and GDP in the West African nation because for the first half of the analysis (2009-2014), there was a positive correlation between GDP and debt but for the subsequent period under analysis, this relationship was negative.

Based on Nigeria’s poor economic growth performance between 2016 and 2019, the country’s debt to GDP ratio has remained constantly low at less than 35% from the year 2016 to 2020. Observers suggest that this debt level is expected to remain low – at less than 37% for the next five years (Global Economy, 2020, p. 6). By international standards, this level of debt is appropriate for a low-income country and estimates suggest that it should be kept at less than 60% to maintain sustainability (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2015, p. 5). This finding helps to answer the first research question of this study, which sought to find the appropriate level of debt suitable for Nigeria.

Additionally, stemming from the findings highlighted above, data from the regression model led to the acceptance of the second hypothesis suggesting that debt financing has not positively affected sustainable economic growth in Nigeria. The findings highlighted are also consistent with others, which have shown that high rates of external debt are detrimental to economic growth potential. The implication of this finding on the Nigeria economy is rooted in the understanding that a diminished economic growth rate would necessitate an increase in debt. This statement is consistent with the extant literature regarding the effect of debt on low-income countries.

The results of the analysis also suggest that Nigeria has a positive co-efficient for the first five years of analysis where it was reporting GDP growth rates above 0% – before 2014. This effect is only significant at a debt incremental level of 1%, but there was an insignificant effect of rising debt levels on the economy for the second part of the analysis, which included an extension of the calculations to the years 2019. In this regard, the first lag of debt-to GDP ratio spurred an economic growth rate of 0.04% between 2009 and 2014, thereby making it possible to hypothesize that the accumulation of debt assets in the periods preceding the analytical timeframe made it easier to report significant gains in economic growth rate within the 2009-2014 period. Afterwards, there was a negative correlation of debt and economic growth.

The findings highlighted above are unique from others mentioned in this paper, because they stretch far back to the 1970s, when Nigeria had negligible debt – both local and domestic (World Bank, 2021, p. 1). The country had only attained self-rule of about 10 years at the time and economic activities were not as robust as they are today. Therefore, much of the economic debt under analysis in this paper started to accrue from the early 1990s to date. Given that our focus of the study has been from 2009 onwards, Nigeria’s economic debt shares a weak relationship with its economic growth. The insights highlighted above contradict those of others, which have examined the relationship effects of debt on a country’s GDP growth. For example, the findings have affirmed a non-linear relationship between Nigeria’s external debt and GDP growth but the findings of other researchers suggest the existence of a linear relationship between the variables. The difference could be because previous researchers have noted a positive correlation between external debt levels and GDP growth rate at a low level of investment (Perez & Dube, 2020, p. 6).

Poor Debt Management Practices in Nigeria

To understand, Nigeria’s weak effect of debt on its economic growth, it is important to evaluate how Japan has managed to achieve high rates of economic growth despite having a high debt to GDP ratio (Zhu et al., 2018, p. 5). The comparison between Nigerian and Japanese public debt management plans is rooted in the fact that the latter’s mounting financial commitments are not problematic, despite being among the highest in the world, yet Nigeria’s debt is considered “risky” (Databod, 2017, p. 3). If this issue is explored in detail, it emerges that the Japanese Debt burden is among the highest in the world. Today, it is estimated to be around $12.2 trillion, which is equivalent to about 240% of the country’s GDP, while Nigeria’s is below 40% (Zhu et al. 2018, p. 34). Japan has had a long history explaining how it managed to accumulate this kind of debt with the earliest reports pointing to the 1990s era when its finance and real estate markets burst, forcing the government to take foreign debt to initiate stimulus packages that would save the economy (p. 54). This action caused its debt burden to breach the 100% mark of its GDP.

In 2010, this percentage doubled to 200% and today it is at 240% (Asia Link Business, 2021, p. 3). Recent policy agreements signed by the Japanese government with its international partners are expected to further increase the percentage of the country’s debt to GDP beyond 250% of its GDP (p. 2). These statistics means that the government of Japan has taken debt that is more than two and half times the size of its economy. The Asian economy is of special interest to this analysis because Japan managed to experience one of the highest rates of economic growth rates in the world between 1960 and 1980s, while accumulating a lot of debt in the process (p. 1). This period was marked by economic transformation, which saw the economy transition from relying on the textile industry to become an advanced technology and manufacturing powerhouse – two industries, which account for Japan’s massive economic appeal around the world. These drastic economic changes were partly funded by debt and it catapulted the economy to be the second biggest one after the US – a position that it held until 2010, when China dislodged it. Using Japan as an example of a country that has prudently used its debt to spur economic growth, the present investigation, suggests that Nigeria’s weak relationship between debt and economic growth could be because of its inefficient debt management policy and not necessarily the size of its debt.

Comparison of Nigeria’s Debt with other African Countries

The comparison between the Nigerian and Japanese debt management models cannot be complete without underscoring the significance of their debt burdens on public perceptions about the strength of their economies. To understand the implications of this comparison, it is important to analyze Nigeria’s debt within the broader context of debt perception in Africa. According to some researchers, the debt levels in African countries are below the 100% to GDP mark, while Japan’s is more than double the percentage (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2015, p. 5). Indeed, the Japanese debt to GDP ratio is in excess of 250%, while the impression out there is that African countries have a much higher debt to GDP ratio compared to other nations in the world. This negative perception of African debt has implications on the management of debt financing in Nigeria because it forces the government to pay higher interest rates than rich nations. Particularly, debt premiums paid by African governments are significantly higher than other governments.