Panic-buying is a relatively common behavioral response to a crisis that people can exhibit in situations that they perceive to be dangerous and unpredictable. Yuen et al. (2020) note that this behavior was previously observed in the wake of major natural disasters, such as the Christchurch earthquake and hurricane Matthew. Hall et al. (2020) note that the global economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic offers a precious opportunity to study the ways of consumption displacement which occur in crises, including panic buying. However, most researchers agree that before the COVID-19 pandemic, this phenomenon has never been addressed as a large-scale issue.

Factors Influencing Consumer Behavior

Several factors can account for an increase in stockpiling and panic-buying behaviors. Access to excessive amounts of information during a crisis can result in a cognitive overload, which, in turn, leads to irrational behavioral patterns. Laato et al. (2020) established that information overload can result in health anxiety, which prompts self-isolation and the tendency to make illogical purchases. Yuen et al. (2020) confirm that the fear of the unknown causes coping behavior in the form of panic-buying and stockpiling. Therefore, it leads to the conclusion that panic-buying can emerge as a form of stress response in certain individuals.

Peer pressure can contribute to irrational decisions in time of crisis as well. Yuen et al. (2020) define panic-buying as herd behavior, in which an individual follows the patterns exhibited by the majority. Friends or members of the family regarded as trusted advisors can also be sources of peer pressure. Prentice et al. (2020) note that when the general sentiment towards stockpiling changed to negative in Australia, panic-buying became less of an issue. Overall, it is clear that in some cases, panic-buying can be a result of imitative behavior, prompted by the trust in the superior judgment of others.

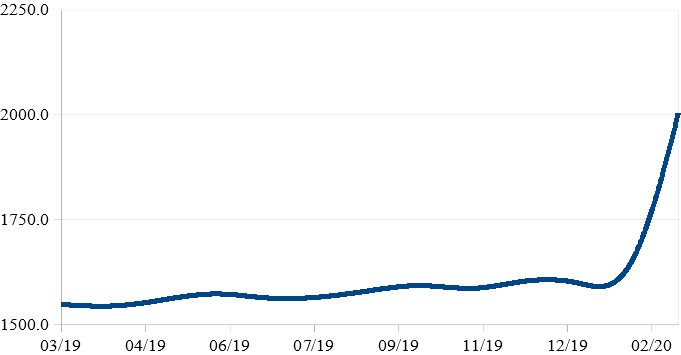

Governmental initiatives can have a massive impact on the public perception of the virus. In March 2020, sales of pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and toiletry goods in Australia peaked at 2 billion dollars, increasing by more than 450 million dollars as compared to March 2019 (see Chart 1). Statistics show that fluctuations in sales for these products were insignificant throughout the year until March 2020, when the government imposed strict regulations to prevent the spread of the virus. Prentice et al. (2020) state that “panic buying and stockpiling commenced in early March and increased sharply towards the end of the month when the lockdown scale was extended” (para. 19). Australian case shows that the measures that governments implement to contain the virus have to be carefully evaluated, as they can have serious adverse effects on society

Preventing Panic Buying: Government as a Guarantor

One of the possible options for the government to control panic buying would be assuming the role of a guarantor and ensuring that toilet paper supply will not be exhausted. Arafat et al. (2020) mention this option and stress the necessity of authorities and related industries issuing assurance statements to convince the populace that no shortages are incoming. Theoretically speaking, such a guarantee could mitigate or even stop the panic buying. According to Dammeyer (2020), one of the notable reasons why people engage in panic buying in the first place is the fear of missing out. In his survey, the statement “I was afraid that suddenly there would not be enough food, medicine, etc.” was ranking relatively high as a reason given by those engaging in panic-buying (Dammeyer, 2020, p. 2). Thus, if the population trusted the government’s efficiency in its role as a guarantor, it would have less incentive to participate in panic-buying. There are also historical precedents for such policies showing them to be moderately successful – in 2008, the Australian government acted as a guarantor to mitigate the deposit run in the country’s banks.

However, there are significant reasons to doubt the effectiveness of this particular solution. To begin with, the government’s actions as a guarantor in the case of panic-buying involving toilet paper would meet with considerable logistical constraints. In the case of the financial crisis of 2008, the government’s guarantee to cover the depositors’ losses required money – the resource that any government has at the ready. Yet one can hardly assume that the government already has a strategic stockpile of toilet paper to ensure its steady and uninterrupted supply in case of shortages. Creating this stockpile will inevitably meet with logistical issues and, even more importantly, will likely have roughly the same negative effects that the panic buying it seeks to alleviate. As Yun et al. (2020) note, the main reason why panic buying is undesirable is that it leads to the large quantities of products being purchased from the market, creating stock out situations. The government creating a strategic toilet paper supply would also lead to the large quantity of it being bought form the market and unavailable for immediate consumption. Considering this, the government guarantee is not an effective solution.

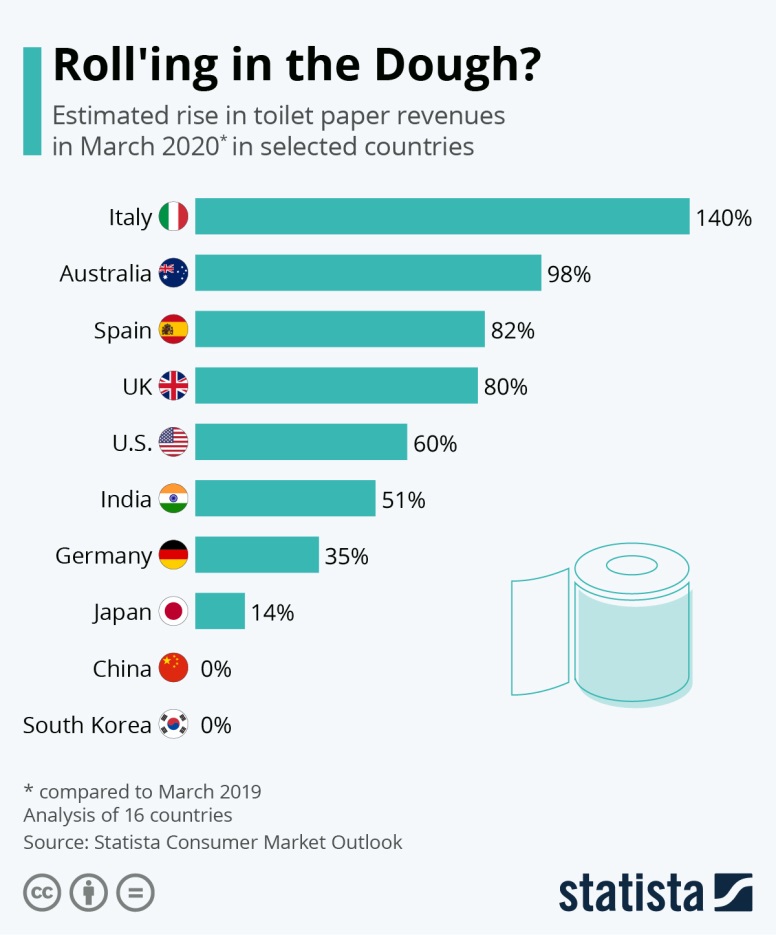

Apart from that, there is another significant downside to the government assuming the role of a regulator. The effectiveness of government assurance depends directly on the degree of popular trust toward the government in question. Dammeyer’s (2020) study reveals that the lack of trust toward the authorities is the second most important factor that incited panic buying during the coronavirus pandemic. The less people trust their government, the more they are likely to succumb to the herd behavior and hoard various commodities out of fear of possible shortages. Diagram 1 demonstrates that Australia’s increase in toilet paper revenues during the coronavirus outbreak was only second to Italy. This fact suggests that the magnitude of Australian panic buying involving toilet paper was among the greatest in the world. This, in turn, means that the Australian population generally does not trust the government’s ability to ensure an adequate supply of necessary goods. Considering this, governmental effort to assume the role of the regulator is unlikely to succeed in the Australian context.

Preventing Panic Buying: Rationing

Another possible option to alleviate the effects of panic buying is imposing limits on the amount of goods a single customer can buy. Arafat et al. (2020) opine that this strategy, also known as rationing, may help to prevent possible shortages. In this case, supermarkets and other outlets will be responsible for enforcing the sales bars to ensure the availability of goods, including toilet paper. Moreover, Arafat et al. (2020) propose to complement this option with cooperation between the government, healthcare services, and outlets to ensure that the people with special needs could obtain necessary supplies at fixed prices. This strategy, also known as the price ceiling, requires the government to compensate for the difference between the fixed prices and the market prices but does not involve overbearing logistical effort. With this consideration in mind, it is a preferable alternative to the strategic stockpiling of toilet paper.

Apart from the fixed prices for the more vulnerable categories of consumers, this approach should also exert a beneficial influence over the market prices. Hall et al. (2020) emphasize that shifts in consumption during crisis situations occur as a result of the interplay between supply availability and consumer demand. In case of panic buying, there is a spiking increase in demand, meaning that the equilibrium will move toward a greater price. Introducing rationing and imposing limits on the amount of toilet paper one customer can buy would correspondingly limit the demand. The equilibrium would still move toward a higher price, as the reason behind the panic buying – the coronavirus outbreak – would still remain in force. Yet limiting the increase in demand would mean that the price growth would not be as severe as without rationing. Thus, rationing as a strategy has three advantages simultaneously: it is simpler to impose, it mitigates the risks of shortages, and it alleviates the price growth resulting from a sudden increase in demand.

Considerations for Toilet Paper Producers

It is hard to argue that the panic buying will allow toilet paper producers to generate greater revenue over a short period of time. Turnover of pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and toiletry goods as a whole reached 2 billion dollars in March 2020, as compared to March 2019 (see Chart 1). In terms of toilet paper specifically, the impact is also significant, with revenue rising by an impressive 98 percent in Australia (see Diagram 1). Yet there is no reason to assume that panic buying would make a significant impact on the toilet paper producers’ revenues in the long run. Laato et al. (2020) note that some people buy considerable amounts of toilet paper as a way of preparing for a prolonged self-isolation period. Self-isolation – or quarantine, when it is imposed – would cause people to live on the stockpiles they have created, rarely is ever going put to shop. Thus, the short-term spiking increase in demand for toilet paper is likely to be followed by a sharp decline to the levels below ordinary.

When speaking of the revenue increase for toilet paper producers due to panic buying, one should also consider the price elasticity of demand. Arafat et al. (2020) stress that panic buying is particularly harmful for such goods as food, fuel, or medical supplies, as the people will still buy them even if the prices rise considerably. Yet toilet paper price is more elastic: unlike food of medical supplies, it does not belong to the first necessity goods, and people can find multiple substitutes for it when and if pressed. Even if one counts supply shortages threatening goods availability and the minuscule costs, price elasticity of toilet paper will still be higher than those of basic necessities. Hence, it is unlikely that panic buying would provide a sustainable revenue increase for toilet paper producers that would be significant in the long run.

Conclusion

As one can see, panic buying of toilet paper in Australian during the COVID-19 pandemic is a classic example of panic buying in a crisis situation. Motivated by peer pressure, concern for not having enough goods, the fears of missing out, and distrust toward the government’s capability to prevent shortages, Australians engaged in panic buying. As a herd behavior, it supported itself for a short period of time, causing the turnover of pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and toiletry goods to skyrockets in March 2020. One possible way for the government to act in this situation would be acting as a guarantor and the assure population that it will prevent shortages – yet this option has considerable logistical and economic downsides. A better approach would be rationing, imposing limits in the amounts a single customer can buy to prevent shortages and alleviate price growth. As for the toilet paper producers, their turnover increase is significant from a short-term perspective but should not be particularly notable in the long run due to the price elasticity of demand.

References

Arafat, S. M. Y., Kar, S. K., & Kabir, R. (2020). Possible controlling measures of panic buying during covid-19. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, (20200521).

Dammeyer, J. (2020). An explorative study of the individual differences associated with consumer stockpiling during the early stages of the 2020 coronavirus outbreak in Europe. Personality and Individual Differences, 167, 110263–110263.

Hall, M. C., Prayag, C., Fieger, P., & Dyason, D. (2020). Beyond panic buying: Consumption displacement and COVID-19. Journal of Service Management, Ahead-of-print(Ahead-of-print).

Kum, F. Y., Xueqin, W., Fei, M., & Kevin, X. L. (2020). The psychological causes of panic buying following a health crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3513).

Laato, S., Islam, A. K. M. N., Farooq, A., & Dhir, A. (2020). Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the covid-19 pandemic: the stimulus-organism-response approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57, 102224–102224.

Prentice, C., Chen, J., & Stantic, B. (2020). Timed intervention in Covid-19 and panic buying. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57.