Learning Objectives

- To discuss the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and differential diagnosis of the disorder (stroke).

- To delineate the diagnostic criteria and management approaches for the disease.

- To present the emergency room guideline for relevant treatment of patients diagnosed with a stroke.

- To present a review of three current research articles supporting the guidelines.

Pathophysiology

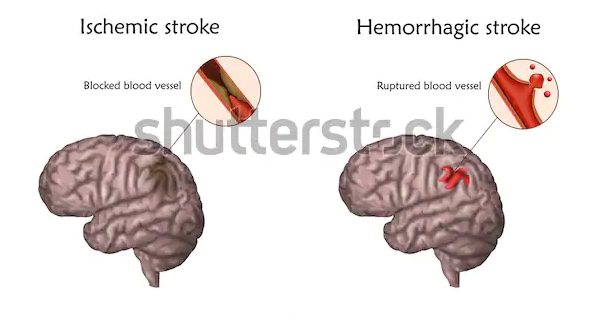

There are two stroke types: hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke.

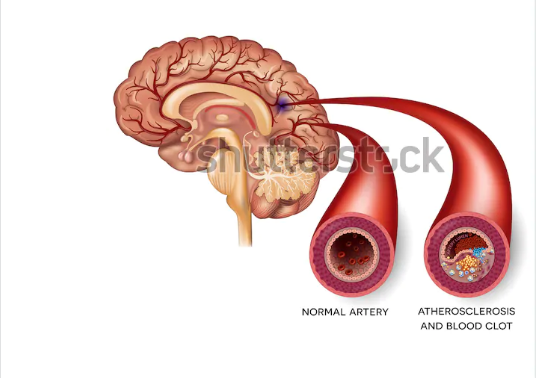

The typical ischemic stroke pathway is lack of adequate flow of blood to perfuse cerebral tissue because of blocked or narrowed arteries within or leading to the brain. Chugh (2019) categorizes ischemic stroke into two primary classes: embolic and thrombotic stroke.

The narrowing or the arteries commonly occurs as a consequence of atherosclerosis – appearance of fatty plaques which line the blood vessels. The increase in the plaques’ size causes the narrowing of the blood vessels and the subsequent decrease in blood flow to the region beyond. Damaged regions of an atherosclerotic plaque can trigger the formation of a blood clot, which, in turn, causes blood vessel blockage – thrombotic stroke.

Embolic stroke occurs when debris or blood clot from any body region, particularly the heart valves, progresses via the circulatory system blocking tapered blood vessels.

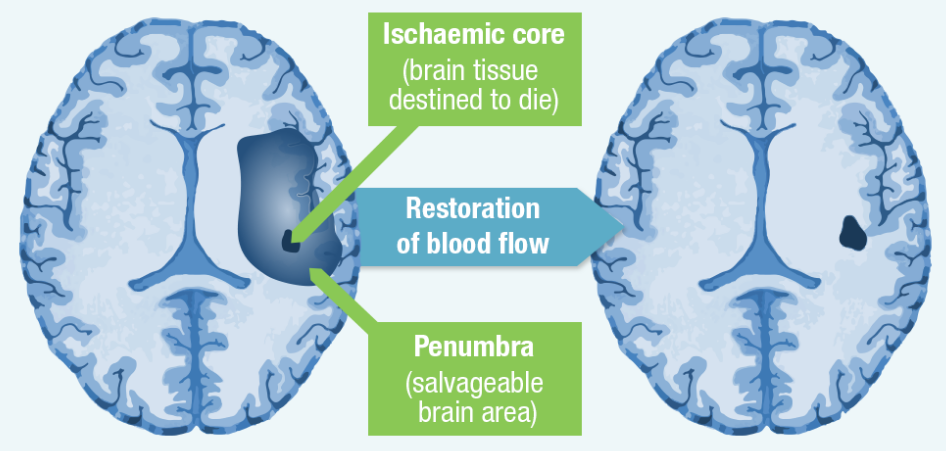

Within the stroke’s core area, blood flow is typically reduced drastically thus impacting the cells’ capacity to recover; they consequently undergo or experience cellular death.

The tissue located in the area surrounding the infarct core – the ischemic penumbra – is usually less severely impacted. It is made functionally silent by the decreased flow of blood but maintains its metabolic activity (Chugh, 2019). Cells within this region are endangered or at risk but their damage is often reversible. They may be exposed to apoptosis following several days or hours but if oxygen delivery and blood flow is restored shortly following stroke’s onset, they are prospectively recoverable.

Pathophysiology of Hemorrhagic Stroke

Hemorrhagic stroke occurs as a result of blood vessels’ rapture causing brain tissue’s compression due to the expanding hematoma; this according to Ojaghihaghighi et al. (2017) can injure and distort tissue. Additionally, the pressure may trigger blood supply loss to the impacted tissue with consequent infarction. According to Ojaghihaghighi et al. (2017), the blood released from the hemorrhage can have direct toxic impacts on brain vasculature and tissue.

Intracerebral hemorrhage is triggered by blood vessel’s rupture and the consequent blood accumulation within the brain. This phenomenon may be triggered by the damage of blood vessels as a consequence of chronic hypertension, the utilization of medications linked with increased blood rates, e.g., antiplatelet agents, thrombolytics, and anticoagulants, or vascular malformations (Ojaghihaghighi et al. 2017).

Subarachnoid hemorrhage occurs as a result of gradual blood collection within the brain dura’s subarachnoid spacing usually triggered by head trauma or cerebral aneurysm’s rapture.

Clinical Manifestations

Irrespective of its etiology, the clinical manifestation of ischemic stroke’s symptoms depends on vessels’ location and collateral circulation’s presence. Nonetheless, embolic strokes have a significant risk of consequent bleeding into the infarcted region, unlike thrombotic strokes (Musuka et al., 2015). A stroke should be considered in patients presenting with any alterations in consciousness level or severe neurologic deficit. Common Stroke-related clinical manifestations include sudden or abrupt decrease in consciousness level, aphasia, nystagmus, ataxia, facial droop, ataxia, vertigo, and dysarthria, diplopia, deficits in the visual field, as well as binocular or monocular visual loss, and hemisensory deficits, and the sudden onset of quadriparesis (rare), monoparesis, or hemiparesis.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage’s symptoms include the abrupt onset of serious headache, meningismus signs with nuchal rigidity, vomiting and nausea, atypical or prolonged syncope, pain associated with eye movement, and photophobia (Ojaghihaghighi et al. 2017).

Ischemic versus Hemorrhagic Stroke

No historical feature can aid in distinguishing hemorrhagic from ischemic stroke. However, nausea, the altered or change in consciousness level, Neck stiffness (LR 5.0), headache, blood pressure – diastolic of >110 mm Hg (LR 4.3), and vomiting are more typical in hemorrhagic stroke (Musuka et al., 2015). Seizures are typical in hemorrhagic stroke compared to the ischemic type. Seizures occur in approximately twenty-eight percent of hemorrhagic strokes, particularly during intracerebral hemorrhage’s onset or within the initial twenty-four hours (Ojaghihaghighi et al. 2017).

Differential Diagnosis

Ischemic stroke: Brain tumor, hemorrhagic stroke, subdural hemorrhage, neurosyphilis, atypical or complex migraine, hypertensive encephalopathy, CNS abscess (Musuka et al., 2015).

Hemorrhage stroke: Ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), Acute hypertensive crisis/Malignant hypertension, Sentinel headache, Sinusitis, Pituitary apoplexy, Cerebral venous thrombosis, Pituitary apoplexy, and cervical artery dissection (Ojaghihaghighi et al. 2017).

Diagnostic Criteria

Physical examination and history remain the foundations of diagnosing stroke. According to Musuka et al. (2015), the most usual physical finding associated with stroke include speech disturbance and focal weakness; its most historic feature of the disorder’s acute onset. Doctors need to quickly evaluate individuals with suspected acute ischemic stroke since the stroke’s acute therapies have a minimal time window of efficacy compared to myocardial infarction therapies.

The exact onset period of symptoms is crucial for ascertaining thrombectomy eligibility. Reliably differentiating between ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage can only be done by neuroimaging. Both diseases are typified by the severe onset of focal manifestations. The NIHSS is a validated decision support tool used to classify early stroke severity; it offers a structured neurologic exam with prognostic and diagnostic value.

The Hunt and Hess grading scheme and the World Federation of Neurosurgeons (WFNS) grading scheme (one which includes the Glasgow Coma Scale) are the clinical scoring systems used for grading aneurysmal SH (Ojaghihaghighi et al. 2017). The Fisher Scale integrates findings or outcomes for NCCT scans (non-contrast computed tomography) (Ojaghihaghighi et al. 2017).

- Laboratory Studies: complete blood count (CBC), basic chemistry panel, coagulation studies, cardiac biomarkers, toxicology tests, and arterial blood gas tests (Musuka et al. 2015).

- Imaging Studies: CT scanning, MRI, transcranial doppler ultrasonography, Echocardiography, and conventional angiography (Musuka et al. 2015).

Disease Management

The objective of acute stroke treatment is to ensure the normalization of perfusion and intervene in the biochemical dysfunction cascade to facilitate the timely salvaging of the penumbra. The tissue in the oligemia region can be maintained or protected by optimizing collateral flow and blood flow restoration in the compromised area. Recanalization approaches such as intra-arterial approaches and administration of IV (intravenous) recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA) try to enhance revascularization to ensure that cells within the penumbra are rescued before the onset of irreversible injuries.

Acute stroke management

Emergent stroke management aims to evaluate the patient’s airway, circulation, and breathing, stabilize the patient, and finish the initial assessment and evaluation, including laboratory and imaging studies, within sixty minutes of the patient’s arrival (Chugh, 2019). Oxygen supplementation and hypoglycemia needs should be identified and managed early during the intervention. Other appropriate therapies include the initiation or use of fibrinolytic therapy, intra-arterial reperfusion, antiplatelet agents, blood pressure control, mechanical thrombectomy, fever control, cerebral edema control, seizure control, acute decompensation, prophylaxis and anticoagulation, neuroprotective agents (Musuka et al. 2015).

Presentation of the Guideline

OHSU Stroke Advisory Committee published the Acute Stroke Practice Guidelines for the Emergency Department in 2018. The guidelines are developed for ischemic stroke, TIAs, intracerebral hemorrhage, and non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. According to the guidelines’ policy statement, OHSU Healthcare has adopted theses practice guidelines in order to define a consistent, evidence-based approach to treating patients who presents with signs and symptoms consistent with acute stroke. However, the responsibility to identify appropriate care for each individual remains with provider themselves. Oregon Health & Science University aims at improving the health and quality of life through excellence, innovation, and leadership in health care, education and research.

The OHSU’s Acute Stroke Practice Guidelines for the Emergency Department (2018) is a valuable source developed for a broad spectrum of healthcare providers, including triage staff, registered nurse, E.D. and stroke team physician, E.D. nurse, and C.N.A (certified nursing assistant). The guidelines involve actions based on duration of symptoms for patients with persistent symptoms onset less than 24 hours, as well as potential acute treatment candidates. The guidelines are structured according to each healthcare professional’s clinical responsibilities. In addition, the guidelines include administration criteria, discharge criteria, and blood pressure management.

Research Supporting the Guideline

- Bai et al. (2019): Intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is an internationally accepted evidence-based efficient treatment for patients with acute ischaemic stroke. However, each affected individuals has different penumbra based on differences in collaterals, cerebral blood flow reserve, and tolerance to ischaemia. This research examined the outcome and safety of implementing DWI/T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) mismatch to guide intravenous tPA therapy for patients with AIS between 4.5 hours and 12 hours of onset. The study analyzed the safety and effectiveness between the time window and tissue window-guided intravenous tPA therapy.

- McDermott et al. (2019): It is crucial for the healthcare providers, advocates, and policy-makers to recognize the current intervention methods and understand their relative efficiency in order to increase tPA treatment rates. The study examined the existing interventions to increase tPA in terms of their considerable effectiveness. The authors uncovered the effectiveness of interventions that aim to increase the use of IV tPA during the management of ischemic stroke. The research findings support the application of such interventions to improve the stroke outcomes.

- Urrutia et al. (2018): The researchers hypothesized that patients awaking with stroke symptoms can be safely treated with intravenous alteplase (IV tPA) using non-contrast head CT (NCHCT), if they comply with all other standard criteria. According to the findings of the study, the administration of IV tPA is feasible and can be a safe treatment approach in wakeup stroke patients presenting within 4.5 hours from awakening, screened with NCHCT. It is a particularly valuable study concerning the applied treatment time window (4.5 hours from awakening) and the use of NCHCT-only patient selection. However, there is a need for a properly powered randomized clinical trial.

References

Bai, Q, Zhao, Z, Lu, L., Shen, J., Zhang, J., Sui, H., Xie, X., Chen, J., Yang, J., & Chen, C. (2019). Treating ischaemic stroke with intravenous tPA beyond 4.5 hours under the guidance of a MRI DWI/T2WI mismatch was safe and effective. Stroke and Vascular Neurology, 4, e000186. Web.

Chugh, C. (2019). Acute ischemic stroke: Management approach. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine, 23(Suppl 2), S140–S146.

McDermott, M., Skolarus, E. L., & Burke, F. J. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to increase stroke thrombolysis. BMC Neurology, 19, 86.

Musuka, D. T., Wilton, S. B., Traboulsi, M., & Hill, D. M. (2015). Diagnosis and management of acute ischemic stroke: Speed is critical. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 187(12), 887–893.

Ojaghihaghighi, S., Vahdati, S. S., Mikaeilpour, A., & Ramouz, A. (2017). Comparison of neurological clinical manifestation in patients with hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke. World Journal of Emergency Medicine, 8(1), 34–38. Web.

OHSU Stroke Advisory Committee (2018). Acute Stroke Practice Guidelines for the Emergency Department. Neurosciences, OHSU.

Urrutia, V. C., Faigle, R., Zeiler, S. R., Marsh, E. B., Bahouth, M., Trevino, C., Dearborn, J., Leigh, R., Rice, S., Lane, K., Saheed, M., Hill, P., & Llinas, R. H. (2018). Safety of intravenous alteplase within 4.5 hours for patients awakening with stroke symptoms. PLoS ONE, 13(5), e0197714.