Analysis of Graduate Employability Skills

The concept of employability

In theory and practice, the concept of employability has been explained by many authors by creating a connection with policy formulation of a country that provides the direction for increasing productivity, creating a flexible workforce, and increasing the employment levels (Clarke 2009). At the individual level, it defines the career path, provides the foundation for individuals to be responsible for their career development.

Boden and Nedeva (2010) argue that educational institutions have the responsibility of molding graduates to become employable in the commercial world. Here, employability is defined as “the possession by an individual of the qualities and competencies required to meet the changing needs of employers and customers and thereby help to realise his or her aspirations and potential in work” (Boden & Nedeva 2010, p.3). To be employable, one is required to develop the skills necessary to be competent in the job market by making positive contributions to the organization the individual is working for (Brown, Hesketh & Williams 2003). To be employable, a graduate should develop the necessary skills to be able to apply numeracy skills, communicate effectively, apply technology, be problem solver, work in teams, have self-management abilities, have business and customer awareness abilities, be entrepreneurial, and have positive attitude. Here, employability is divided into various categories among which include initiative, labour market performance, initiative, manpower policy, and flow employability. In addition, social medical and Dichotomic employability are also other forms of employability that have been recognised in the realms of human resource management.

Critical analysis of employability skills within HRM

The importance of graduate employability skills cannot be underestimated especially when graduates from higher levels of learning institutions continue to get into the job market as a human resource manager (Clarke & Patrickson 2008). For one to qualify to work as human resource manager, it is critical to acquire employable skills which include “Planning, organisational, sponsorship knowledge, marketing, human resource management, administration, public relations and finance skills” (Jackson 2010, p.4) were additional skills recommended for the graduate. A study on the order of importance of the skills requirements show that additional skills should include “time management, leadership, flexibility, communication and people management” (Jackson 2010, p.4).

A critical analysis shows that those skills need to be divided into career specific and career neutral skills (Clarke 2013). The criticality of self-awareness, social awareness, time and self-management, and relationship management cannot be underestimated because they are critical for a graduate to be employable. Employability skills are resources that provide the performance indicators that the government uses to measure the knowledge based economy. However, the skills are lumped together and one fails to draw a line to distinguish them and their short and long term effects on the career development of the graduate (Inkson, Gunz, Ganesh & Roper 2012). Besides, it is difficult to clearly define career specific skills that constitute the technical skills which underpin the analytical, professional, and technical skills of the graduate within the human resource management discipline (Clarke 2009). It is important to note that career neutral skills that consist of initiative, leadership, and problem solving besides the effective use of language to communicate and express oneself in a decisive manner.

A critical analysis of the study by Clarke (2009) shows that the market has many jobs which cannot be filled by graduates from higher learning institutions despite possessing the skills such as self-management. Self-management is taught without a specific job environment in mind. However, for one to work in the human resource management discipline, the self-management skills enables them to manage time effectively, be assertive, resilient, and flexible among other attributes.

It is worth mentioning that for a graduate within the human resource management discipline, it takes one many years of academic work to develop the skills that prepare them for the job market, but get the shock when they are unable to secure the jobs. The rationale is that graduates must develop the requisite skills for them to make valuable contributions to the labor market for economic, cultural, and social development of the nation.

Besides, other skills necessary for a graduate within the human resource management discipline to make positive contributions to the job market is decisive thinking. Decisive thinking enables the graduate to make the right decisions to recruit, reward, appraise, direct, innovate, train and develop, and design work to become successful in the execution of organizational tasks and responsibilities. The positive side of the skills is that they enable the human resource manager to make robust decisions based on analytical information obtained about a leadership problem. There are diverse skills such as ability to communicate effectively and clearly in addition to possessing oral and written communication skills, ability to work and lead teams, and the ability to solve problems that arise at the work place. A critique of the skills indicates that they are indispensable for the human resource manager to operate efficiently. The downside of acquiring the skills is that they vary from one job environment.

People skills provide the foundation for the graduate to work in teams, lead, negotiate, and network with other people and institutions. However, as much as those skills are necessary, teaching them in the school environment does not necessarily translate into the job environment. One has to learn them when in the probation period to be able to map the skills into the one’s knowledge and experience map. Such an approach is deficient of the fact that such skills prepare one to join the job market and be ready to learn because of poor academic knowledge. The aim of acquiring academic knowledge is to prepare oneself to apply them in the job environment and to contribute positively to the operations of an organization. Learning is the key element. Learning is a continuous process that enables graduate employees to improve their innovation skills and contribute to the development of the organization.

Planning and organization, initiative and enterprise, technology (use of word processing software such as spreadsheets), communication and literacy (ability to formulate clear and logically organized statements), entrepreneurial skills, and self-management contribute to the employability skills that is necessary for a graduate to be accepted in the job market. The self-management skill defines the behaviour, attitudes, actions, teamwork, goals, and conflict resolution capabilities of an employable graduate. Besides, problems solving skills provide the graduate employee with the skills necessary to think critically and solve problems that happen at the place of work. It is necessary to learn the skill because it molds various aspects of the graduate in preparing them for the job market. However, such molding cannot produce the graduate ready to work in a new work environment without experience. Despite the proposition, some authors recommend that a graduate can learn those skills in the job market once they have been employed. The disparity in the inculcation of skills within academic institutions and the job environment shows the need for career development and the need to establish linkage between learning institutions and business organizations. The results show that graduates need to be recruited from leaning institutions after they have been exposed to the busyness environment for their career development (Feldman & Ng 2007). For instance, teamwork enables the graduate to contribute productively towards the tasks and activities within an organization. Without the team skills, it is not possible for a graduate to promote creativity and innovation through the cross fertilization of ideas. That is besides creating an environment of interdependence, cooperation, respect for others, and ability to negotiate situations.

However, failure to acquire the skills leads to loss of effort, poor problem solving and decision making skills, and low creativity. However, with effective team leadership skills and once in the job, it is possible for the graduate to promote effective execution of team activities such as autonomy, provide opportunities for learning and skills development, and be able to meet the varied demands of each team member and the importance of such skills cannot be underestimated.

While some authors have ranked etiquette and good manners at the bottom of the scale for evaluating their importance, it is notable that such skills make significant contributions to an employable graduate.

Evidence of an employability adverts

Examples of employability exist in various media outlets within the human resource management discipline. Different companies emphasize on different skills. For instance, an advert for a human resource manager posted online required someone who could fill a vacant position at the MDwise Human Resource Department (MDwise 1). The advert detailed the skills necessary for the applicant to qualify for the vacancy. One was required to meet the competence necessary to work as a human resource manager for the company. Some of the employability skills required include excellent interviewing and listening skills, ability to lead and teach others in addition to the ability to resolve conflict when they happen within the working environment (Lyons, Eddy, Ng & Schweitzer 2014). Additional skills include good working relationships among the staff members, time management, understanding the legal implications of the human resource discipline, ability to train and develop employees, and excellent written and communication skills. However, a criticism of the skills requirements for the advertised vacancy showed that some of the skills could be developed at the place of work, depending on the level of one’s self-awareness and ability to learn.

On the basis of an analytical report by Knight and Yorke (2004) and Hall (2004), it was evident from the advert that the elements in the advert were not listed in order of importance. However, the order of importance should be in accordance with the following: self-management, team working, business and customer awareness, problems solving, communication and literacy, application and literacy, application of information technology, and positive attitude.

Personal employability skills by drawing on self-awareness

Self-awareness is a tool that provides a clear framework for evaluating my graduate employability skills to work as a human resource manager. To evaluate myself and determine the level of employability, I used the self-awareness tool that is defined by self-confidence, accurate self-assessment, and emotional self-awareness (Sullivan & Baruch 2009). The elements of self-awareness include motivation, preferences, and personality was important in influencing the judgment I could make in my career development, decisions and how to interact with other people. After a candid review, the results showed that I lacked certain employability skills. That was despite my qualifications as a graduate. I realised that sometimes lack of self-confidence could get in my way to be effective in self-management. Drawing on the study by Rodrigues and Guest (2010), the argument is besides my inability to act as a good team leader and to develop positive attitude. Besides, my creative skills in contributing new ideas as a human resource manager were inadequate.

After an accurate self-assessment, my problem solving skills were inadequate for a human resource manager. However, I was skilled business and customer relationships besides the academic knowledge acquired in school. The rationale was that I was knowledgeable in the key drivers of business success such as the connection between customer satisfaction and loyalty, importance of risks on business operations, and innovation and its importance in the business environment.

Based on Adamson, Doherty and Viney (1998) studies on career development, I conducted an assessment of my emotional self-awareness and concluded that sometimes I do not measure up to the skills required to control my emotions such as the ability to keep calm when threatened, keep calm when under pressure, and motivate myself even after getting negative feedbacks from my prospective employer. However, I had good relationship with others because I could intervene and make comments when necessary and encourage others as well to work hard towards the accomplishments of their career objectives using carefully worded statements (Baruch 2004). Typically, I have good decision making skills, and a good understanding of the human resource management working environment. That is because I am able to collaborate extensively with others, provide satisfactory services to customers, test new ideas, and work in a highly stressful environment.

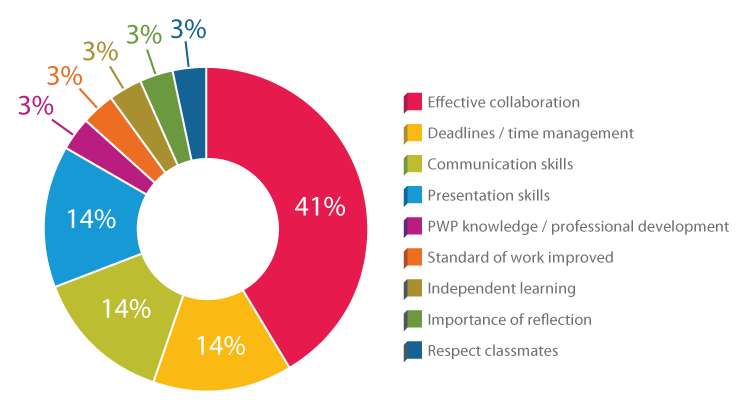

Based on the Johari window of self-awareness, which provides a model for personal assessment on personal development, understanding of group relationships, and group development, I realised that some personal aspects such as “being known by the person about myself is also known by others” could not qualify my character to fit into the open/free area. Some aspects about myself could fit me into the blind area, unknown area, and hidden areas. The conclusion was for me to work and undo some of my attributes that placed me in the unknown area, blind area, hidden area, and move open area. The feedback from my employer is as shown in figure 1 below.

Figure 1 show my employability assessment feedback which shows that I have good collaboration skills which constitute 41% of the elements that were assessed, 14% time management abilities, 14% effectiveness in communication skills, 14% presentation skills, 3% effective collaboration, 3% respect for classmates, and the rest 3% for all the remaining elements. Based on empirical evidence of the feedback from the prospective employer, I have decided to enhance my employability skills based on an action plan that is outlined below.

A 2-3 year skills enhancement action plan

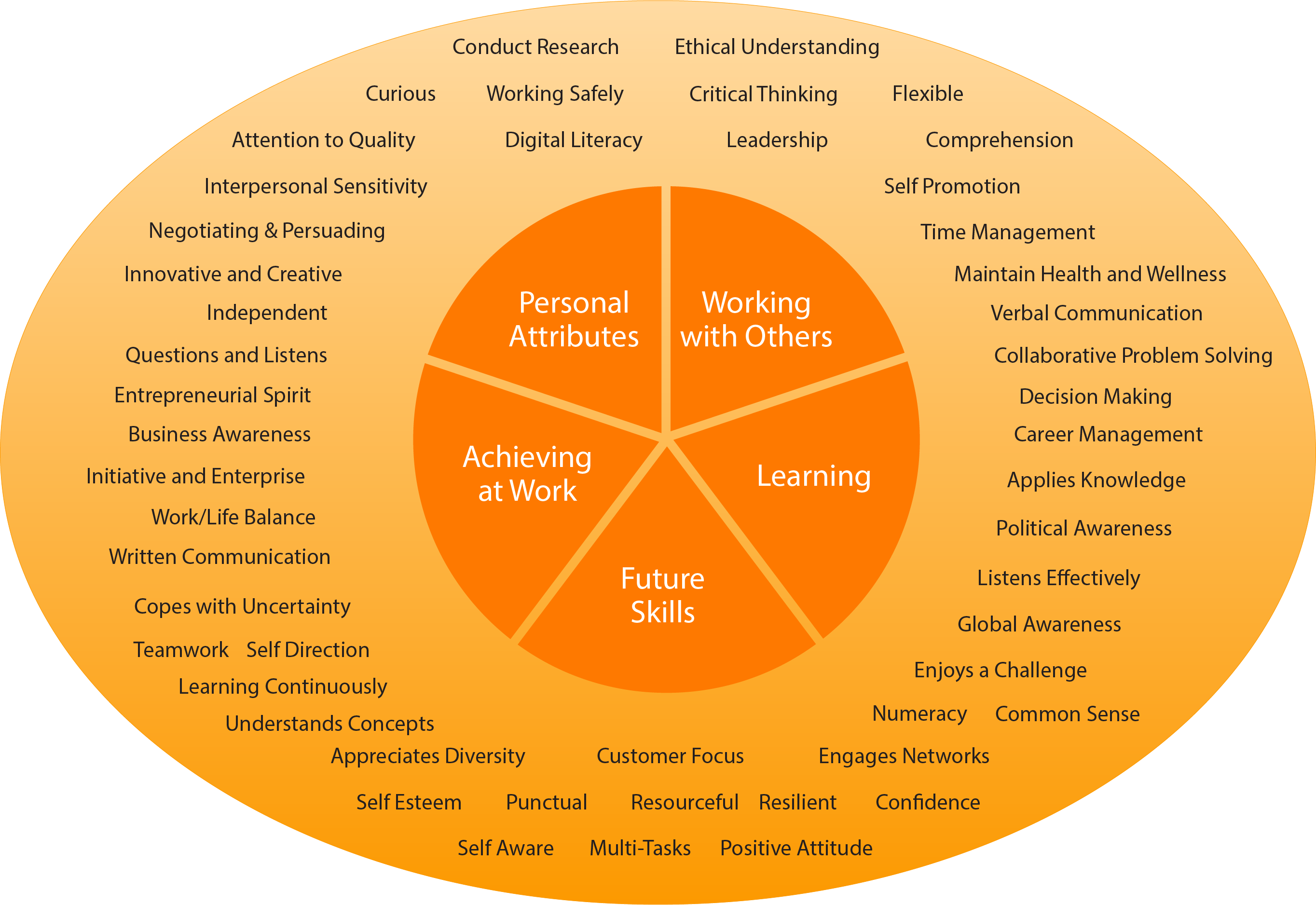

Adamson, Doherty and Viney (1998) provide detailed analysis of career development showing how a graduate should go about enhancing their individual skills to be consistent with the skills requirements in the job market. Based on that argument and research results, I have developed a plan to enhance my skills to become an employable graduate. Figure 2 shows the elements that I intend to factor into the action plan to enhance my employability skills. I intend to develop four attributes in my action plan out of the five elements in the quadrants shown in the figure to enhance my skills. According to night and Yorke (2003) and Knight and Yorke (2004), the elements are personal attributes, working with others, learning, future skills, and achieving work respectively. However, I have selected the first four and left out the last attribute. Different authors use different terms to describe the same elements and in this case. The basis for the action plan is career development based on the attributes in figure 2.

I plan to improve my personal attributes in the first year based on the results of self-analysis, which include behavior, personality, perceptions, and attitude. My plan is to achieve personal development, which include interpersonal sensitivity, negotiation and persuasion skills, independence, innovation and creative skills. By acquiring the skills set in the first six months of the year, I hope to become more honest, flexible, resilient, and self-starting in different job environment. In the second year, I plan to improve on the remaining elements working with others, learning, and my future skills development for my career advancement.

References

Adamson, S J, Doherty, N & Viney, C 1998, ‘The Meanings of Career Revisited: Implications for Theory and Practice’, British Journal of Management, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 251–259.

Baruch, Y 2004, ‘Transforming careers: from linear to multidirectional career paths: Organizational and individual perspectives’, Career Development International, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 58 – 73

Boden, R & Nedeva, M 2010, ‘Employing discourse: universities and graduate ‘employability’, Journal of Education Policy, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 37-54

Brown, P, Hesketh, A & Williams, S 2003, ‘Employability in a knowledge driven economy’, Journal of Education and work, vol. 2, no. 16, pp. 107-26

Clarke M & Patrickson, M 2008, ‘The new covenant of employability’, Employee Relations, vol. 30, no. 2, pp.121 – 141

Clarke, M 2009, ‘Plodders, pragmatists, visionaries and opportunists: career patterns and employability”, Career Development International, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. pp.8 – 28

Clarke, M 2013, ‘The organizational career: not dead but in need of redefinition’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 24:4, no. 1, pp. 684-703

Feldman, D C & Ng, T W H 2007, ‘Careers: Mobility, Embeddedness, and Success’, Journal of Management, vol. 1, no. 33, pp. 33-350

Hall, D T 2004, ‘The protean career: A quarter-century journey’, Journal of Vocational Behavior’, vol. 1, no. 65, pp. 1-13

Inkson, K, Gunz, H, Ganesh, S & Roper, J 2012, ‘Boundaryless Careers: Bringing Back Boundaries’, Organization Studies, vol. 33 no. 1, pp. 323-340

Jackson, D 2010, ‘An international profile of industry-relevant competencies and skill gaps in modern graduates’, International Journal of Management Education, vol. 3, no. 8, pp. 29-58

Knight, P & Yorke, M 2003, Assessment, Learning and Employability, OUP, Oxford

Knight, P & Yorke, M 2004, Learning, Curriculum and Employability in Higher Education, Routledge, London.

Lyons, S, Eddy, S Ng, E & Schweitzer, L 2014, ‘Changing Demographics and the Shifting Nature of Careers: Implications for Research and Human Resource Development’, Human Resource Development Review, vol.13: pp 181-206

MDwise: Human Resources Manager, n.d, Web.

Rodrigues, R & Guest, D 2010, ‘Have careers become boundaryless?’ Human Relations. vol. 63, no. 8, pp. 1157-1175

Sullivan, S & Baruch, Y 2009, ‘Advances in Career Theory and Research: A Critical Review and Agenda for Future Exploration’, Journal of Management, vol. 35, no. :6, pp. 1542-1571