Abstract

Background: Ebola and Marburg viruses are deadly Filoviruses that are significantly infectious. The viruses have not been given the necessary attention, posing a significant challenge to the public. They cause massive deaths when an outbreak occurs, hence the need for general knowledge regarding the virus to enable the public members to have the necessary information when an outbreak occurs. They affect people of all ages, including physicians and other medical care providers.

Methods: The literature review methodology is used to collect data from articles that have been published from 2016 to date. The search method involves using a variety of definitions to search for articles in databases such as Publication Med, Open library, The free library, Science direct, Booksc, World public library, Google scholar, Digi library, and World Health Organization (WHO) publications. Inclusion and exclusion criteria ensure that studies that meet requirements are included.

Results: Marburg and Ebola viruses have resulted in various outbreaks that have caused many infections and deaths. Marburg and Ebola viruses are transmitted from fruit bats to animals through food products, contact with their feces, and animal-to-human contact. They both have the same symptoms.

Conclusion: Treatments for the Ebola virus have been developed, although the available treatment is effective for the Zaire Ebola virus. However, for the Marburg virus, it depends only on supportive care.

Introduction

Background

Ebola and Marburg virus are deadly viruses that result in significant outbreaks with high fatalities. These viruses have been underestimated in the current society because their outbreaks have been experienced in a few parts of the world. However, the number of fatalities experienced in those areas is very high. The two viruses have been known to cause many deaths whenever an outbreak occurs. The public members are at potential risk as there is less concern regarding the two viruses. The public must be knowledgeable about the two viruses to enable easy handling of them in case of an outbreak. The first case of the Ebola virus was reported in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in 1976.

The infection rate of Ebola in the African region has been growing significantly since 2000. This trend has made it recognizable among the top infectious viruses globally. Ebola virus is mainly distributed in West Africa, the United Kingdom, Spain, Thailand, the United States, and Canada (Becker et al., 2018). Marburg virus is also a deadly disease first reported in 1967 in the capital city of Serbia, Belgrade. Germany also reported the same case in this period (Peterson & Samy, 2016). In Africa, the first case of the Marburg virus was reported in Uganda.

Problem Statement

The risky nature of Ebola and Marburg viruses have been underrated. Ebola affects people of any age, with more than 80% affecting adults between 21 and 60 (Kellerborg et al., 2020). Occupations with a high risk of Ebola virus infection include laboratory technicians, nurses, and physician assistants. Marburg virus also affects individuals of all ages, with high cases in adults because they are physically active. Therefore, it is essential to compare the two viruses in epidemiology, etiology, and symptoms to identify their relationship. Furthermore, this will provide the public members with the necessary information to create awareness of the two viruses whenever an outbreak occurs.

Research Question

What is the comparison between Ebola and the Marburg viruses regarding epidemiology, etiology, and symptoms?

Materials and Methods

Identifying the Research Question

The research question was identified through a series of activities. First, the researcher analyzed various literature materials that provide information on multiple viruses that have become common in many parts of the world because of less attention from the healthcare sector and other health organizations. These viruses have resulted in multiple cases and are considered deadly but have not received the required attention, which would help the members of the public identify them. Furthermore, the provided attention makes it a vital choice to prevent an upcoming pandemic that can be controlled with necessary measures and research. Second, attending medical conferences has also played a crucial role in identifying the research question. The conferences provide the required information on viruses that are considered significant and which need attention. Lastly, world news has provided an essential section for identifying the underlying problem affecting certain groups of people. This provides the necessary clue for the identification of the research question.

Search Methods for Identifying Relevant Studies

The research used a variety of definitions of epidemiology, etiology, and symptoms to ensure that the necessary articles were included in the research study. The research study involved eight databases, including Publication Med, Open library, The free library, Science direct, Booksc, World public library, Google scholar, Digi library, and World Health Organization (WHO) publications. The search term used to retrieve research articles includes “Ebola virus,” Marburg virus,” “Comparison of Ebola and Marburg virus,” and “Ebola epidemiology.” Other search terms are; “Marburg epidemiology,” “Ebola etiology,” “Marburg etiology,” “Ebola symptoms,” and “Marburg symptoms.” Titles, abstracts, and keywords of the articles were scanned and read to determine whether the materials were suitable to be included in the research. To ensure that the selected articles are relevant to the research study, the main text of the articles was investigated. Articles that clearly explained the epidemiology of either Marburg, Ebola virus, or both were scrutinized further as most of them provided more information on areas such as etiology and comparison. Furthermore, articles that address the history of the two infections were selected for inclusion.

Study Selection

This phase was introduced to limit the range of materials selected during the search process. It was vital to ensure that materials were either included or excluded from the research study depending on whether they met the set criteria. This step was intended to assess the available potential which answers the research question directly or at least parts of the questions such as epidemiology, etiology, or the comparison between Ebola and Marburg virus. The researcher focused on retrieving articles based on the inputted search term, the specified journal, year of publication, and the citation number of the article selected.

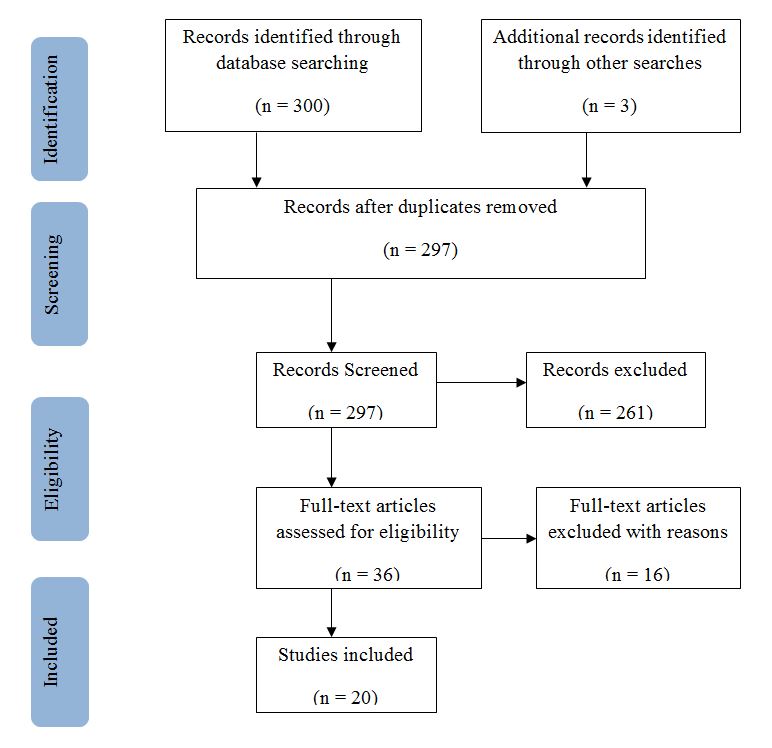

Articles that did not involve Marburg or the Ebola virus were excluded. After refining the search process, 300 articles were identified. Three more sources were retrieved from the WHO publications, making 303 articles. Six articles were removed because they were duplicates, making 297 articles. The search strategy later focused on screening the selected articles, and 261 articles were removed. The remaining 36 articles were subjected to eligibility analysis which involved checking abstracts and eliminating 16 articles. The initial literature review was conducted between December 2021 and May 2022.

Charting the Data, Collating, Summarizing

Table 1: Literature review findings

Reporting the Results

Epidemiology

Both Ebola and Marburg virus are among known dangerous filoviruses. Their outbreak results in hemorrhagic fevers among humans and non-human primates involving other animals such as vertebrates (Ndjoyi et al., 2020). They result in a high number of deaths as they are very infectious. Ebola was first reported in 1976 in Zaire and Sudan. Ebola virus disease (EVD) has a case fatality rate of about 78%, which is risky. EVD has resulted in more than 30 outbreaks over four subsequent decades (Li et al., 2016). In 2014, there was a significant Ebola outbreak in the West African region where it was transferred due to human-to-human contact. The outbreak spread significantly, and in November 2015, the infection was high resulting in 28,600 cases and 11,300 deaths worldwide (Li et al., 2016). This resulted in a global epidemic of EBV, and many countries participate in the fight against the infection. World Health Organization (WHO), governments such as China, and other non-governmental institutions responded to the infection.

Ebola virus is considered the deadliest of all the filoviruses because of the number of lives and infections it has caused in Africa and globally. According to the study conducted by Ndjoyi et al. (2020), the Ebola virus is the most deadly filovirus, with a death percentage of approximately 53 to 88 in the regions identified. For instance, the Sudan Epidemic had 284 cases with 151 deaths (Ndjoyi et al., 2020). In Zaire, there were 318 cases where 280 resulted in the deaths of the infected individuals. Since then, the Ebola epidemic has been reported in various parts of the world. In 1979, Ebola was reported in Nzara, in 1996 in the United States of America, in 1994 in Ivory Coast, and 1995 in Zaire and Gabon. Gabon experienced various epidemics, one took place in 1994, and two occurred in 1996. Other places, such as England, had laboratory contamination cases of Ebola in 1976. Russia experienced the same issue in 1997. Secondary infection was reported in South Africa in 1996 (Ndjoyi et al., 2020). In 2000, Uganda reported a new variant of Ebola, resulting in isolation.

Marburg Virus Disease (MVD) is an infectious disease resulting from the Marburg virus. The disease was first identified in 1967 after the outbreak of hemorrhagic fever in laboratories in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, and Frankfurt, Germany. Marburg disease has a fatality percentage rate of 32 to 88 (Okonji et al., 2022). After these incidents in Europe, various cases have been reported in other parts of the world. In 1975, three cases of MVD were reported in South Africa. Kenya reported three cases; two were in 1980 and one in 1987. The cases reported in Kenya were mainly linked to caves infested with bats. In 1998, there was a significant epidemic in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which caused 80 percent of the death in the region. In 1999, DRC reported 18 cases that led to the doctor’s death handling the cases (Ndjoyi et al., 2020). In 2000 the number of cases reported decreased significantly in Zimbabwe, Kenya, and South Africa. In 2004, Angola reported 400 cases of MBV, where one death was also reported from the disease (Ndjoyi et al., 2020). In 2005, Angola reported 387 MBV cases that resulted in 329 deaths (Ndjoyi et al., 2020).

The subsequent outbreak was reported in 2007, where three cases were identified, resulting in a single death. Another outbreak also in Uganda had 26 confirmed cases with a fatality rate of 58% (Okonji et al., 2022). The source of the disease was in Ibands district, which spread to other areas such as Kampala, Kabale, Mbarara, and Kamwenge. In 2014, Uganda experienced another outbreak in the city of Kampala (Okonji et al., 2022). Other affected areas include the United States of America and the Netherlands, where they had one case linked to the outbreak in Uganda. In 2017, WHO declared the Marburg epidemic due to the death of 3 people.

Etiology

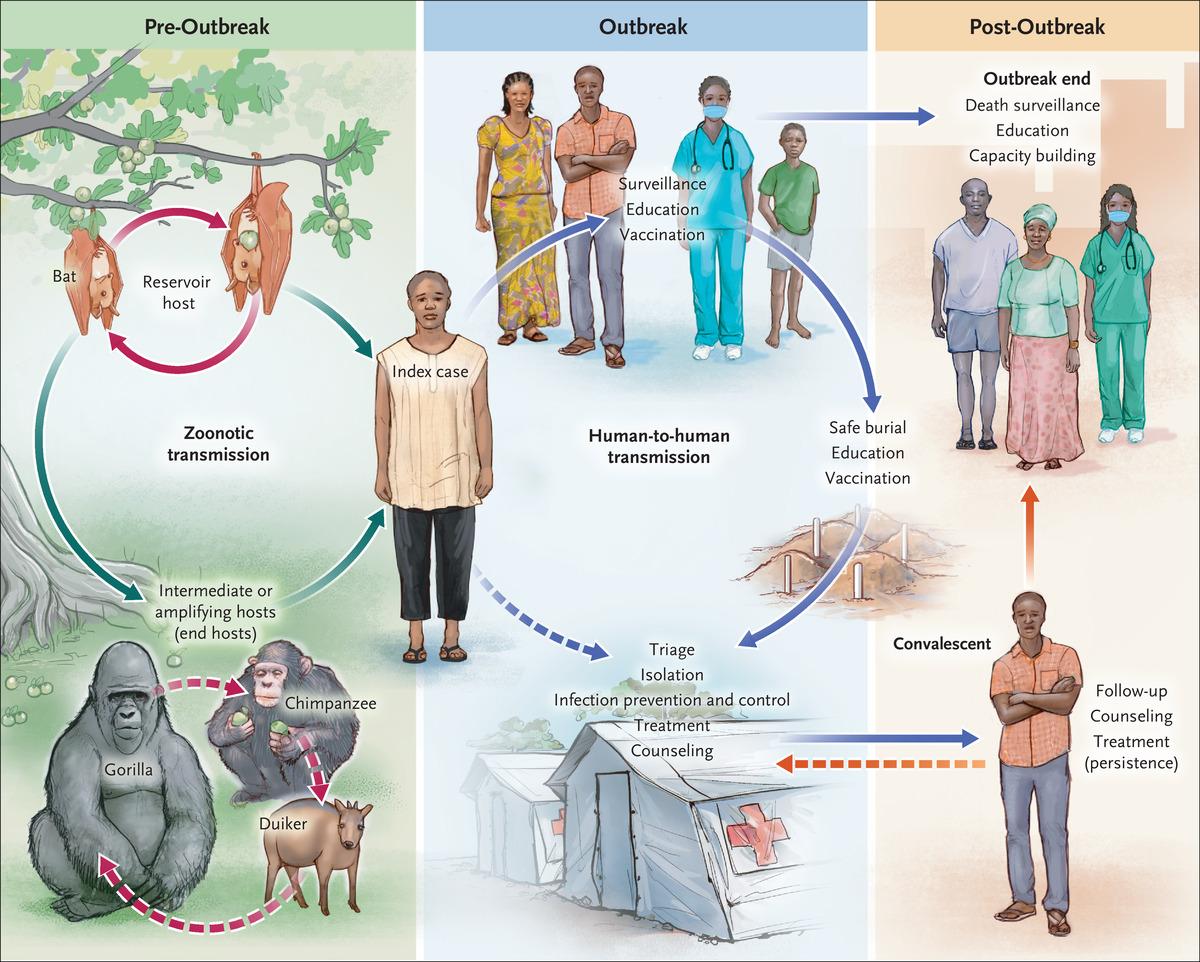

Ebola and Marburg virus are from the Filoviridae family, which involves Cuevavirus, Marburg virus, and Ebolavirus genera. Five species are from the Ebolavirus genera, and these include Tai Forest ebolavirus (TAV), Reston ebolavirus (RESV), Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV), Bundibogyo ebolavirus (BDV), and Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV). The marburgvirus genus has a single species, Marburg marburgvirus (Ndjoyi et al., 2020). The genus Cuevavirus has one species which is Llovirus. These viruses have a 6 and U shape enclosed within single-stranded RNA that has a negative polarity with a size of 19 kb (Li et al., 2016). The reservoir of the Ebola virus is fruit bats, and individuals affected by this virus are because of the contact between their excrements and fruits that the bats have infected. Furthermore, handling corpses that the Ebola virus has infected, whether human or animal, leads to infection (Ndjoyi et al., 2020). Contamination through interhuman results during the interaction between healthcare givers and the patients, which involves their blood and other excretory products.

Transmission through sexual transmission is identified because of the presence of the virus in the patient’s semen. The Ebola virus can survive within the semen of the patient up to 21 days after recovery (Patel & Shah, 2022). After an individual has been infected with the Ebola virus, it incubates within the host, which takes days to weeks. During this period, the individual is not contagious. The virus penetrates the host through the mucosal membrane or damaged skin. Nevertheless, the membrane does not need to be damaged for the virus to enter the new host. Food products also play a critical role in the transmission of EBOV. Plants also have a significant role in transmitting the Ebola virus (Singh et al., 2017). This is a result of eating food products that the virus has infected. Fruit bats release their saliva into food products such as fruits which later get into the human body through ingestion. However, infection through food products is dependent on the virus’s ability to survive.

Marburg virus is also transmitted through contact between primates and the feces or other food products that the Rousettus aegyptiacus fruit bats have eaten. Transmission from one person to another is through fluid contact, direct blood or tissues, and secretions of the infected individual. Similar to the Ebola virus, the Marburg virus is also transmitted through sexual intercourse (Ristanović et al., 2020; Okonji et al., 2022). The incubation of the Marburg virus is between 2 and 21 days, after which individuals begin to show symptoms of the MVD. Unlike EVD, the Marburg virus reservoir has been identified as R. aegyptiacus bats trapped in the mines and other caves in Uganda. Approximately 2.5 percent of the R. aegyptiacus bats have tested positive for the Marburg virus.

Symptoms

Patients infected with EBOV show symptoms such as vomiting or nausea, weakness, diarrhea, fever, elevated body temperature, headache, vomiting, hemorrhage, muscle pain, and abdominal pain. Ebola and Marburg have almost the same symptoms as the patients appear prostate (Li et al., 2016). The papulovesicular, maculopapular or nonpruriginous rash appears after 5 to 7 days (Ristanović et al., 2020). Severe symptoms of both viruses include acute renal failure, pancreatitis, coma, hepatic insufficiency, and mental clouding (Nyakarahuka et al., 2017). Other Marburg symptoms include bloody stool, anorexia, difficulty swallowing, upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding, vomiting blood, and nose bleeding.

Analysis

Findings

Ebola and Marburg virus are deadly infectious diseases that lead to hemorrhagic that may later lead to death. For Ebola virus, it has resulted in numerous infections and deaths, with a case fatality of 78% (Ndjoyi et al., 2020). EVD has resulted in several outbreaks in the last four decades (Ndjoyi et al., 2020). This shows that Ebola is the most deadly viral disease among the filovirus. Ebola is mainly associated with tropical regions such as Africa, and most of the outbreaks are in West Africa. However, EVD spreads significantly fast from one organism to another, leading to a high infection rate. Apart from tropical regions, EVD cases have been identified in other areas such as the United States of America, England, and Russia. MVD has a fatality rate that ranges from 32% to 88% (Okonji et al., 2022). This virus also has a high number of cases in the tropical region. A significant Marburg outbreak occurred in DRC in 1998, where it caused more than 80% of the deaths (Okonji et al., 2022). The virus has been reported in Yugoslavia, Germany, Kenya, South Korea, the democratic republic of Congo (DRC), South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Uganda.

Ebola and Marburg virus belongs to the Filoviridae family. Ebola virus has five species in its genera which are Tai Forest ebolavirus (TAV), Reston ebolavirus (RESV), Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV), and Bundibogyo ebolavirus (BDV), and Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV). Marburg virus has only one species: Marburg marburgvirus (Ndjoyi et al., 2020). Ebola is transmitted from fruit bats to humans and animals through various contacts such as food products, animal to human contact, and when animals and humans get in contact with excretory products of fruit bats. Other modes of transmission are through sexual fluids, as the Ebola virus has been identified to be in semen even after Ebola patients have recovered from the infection (Patel & Shah, 2022). Marburg virus is also transmitted through contact between primates and infected products such as food and feces. Rousettus aegyptiacus fruit bats are the reservoir of the Marburg virus (Ristanović et al., 2020). Marburg and Ebola virus infections have the same symptoms. This includes hemorrhage, muscle pain, headache, high body temperature, abdominal pain, body weakness, and fever.

Differences

Ebola and the Marburg virus are two different filoviruses but have clinically the same effects. Several differences between the two viruses, including fatality rate and reservoir. Ebola has a higher fatality rate than the Marburg virus, making it the most deadly among filoviruses (Ristanović et al., 2020). The most notable is 2015, which led to 11,300 deaths globally. The reservoir of the Marburg virus has been identified exactly to be Rousettus aegyptiacus fruit bats, while for Ebola, the exact reservoir has not been fully identified.

Advances

Compared to the Marburg virus, medical advancement has been made on the Ebola virus. The 2020 Zaire Ebola outbreak proved responsive to Inmazeb (REGN-EB3). This drug has three antibodies which include odesivimab-ebgn, maftivimab, and maftivimab. Ebanga (Ansuvimab-zkyl) is a monoclonal antibody (CDC, 2021). The antibodies act like natural antibodies that prevent the virus from replicating after getting into the body. They bind with the glycoproteins of the Ebola virus hence preventing them from entering the cells.

Gaps

Marburg virus does not have specific medical treatment for the infection. It is currently dependent on supportive care for the recovery of the patients. Furthermore, vaccines for both infections have not yet been developed.

Limitations

The limitation of the current study is in the methodology used. Most of the articles have solely dependent on the literature review. Furthermore, few studies have focused on the Marburg virus because of its high infection rate and mortality.

Conclusion

Solutions

Ebola virus requires further research to identify the treatment of other variants such as Tai Forest ebolavirus (TAV), Reston ebolavirus (RESV), Bundibogyo ebolavirus (BDV), and Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV). The current treatment is only effective for the Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV). On the other hand, the Marburg virus has received less attention despite being a deadly filovirus. This virus requires further research to ensure that treatments are identified to prevent massive deaths in the future in case of an outbreak. Additionally, studies need to increase their attention on this infection.

Implications

The findings of this research are essential in ensuring providing the necessary data in light of Ebola and the Marburg virus. The results suggest that Ebola is a significant deadly infection with an unpredictable outbreak. Similar to the Ebola virus, Marburg is also infectious, affecting individuals of all ages. The finding of this research provides the necessary information for the subsequent research as it provides information on epidemiology, etiology, and symptoms.

Significance

The outcome of this research provides critical information regarding the two deadly Filoviruses. Marburg and Ebola viruses have resulted in a significant outbreak in their history. The findings show a need for the development of vaccines and extensive research on these viruses. The study has provided similarities between the two infections and the main differences. The findings show that the symptoms between Marburg and Ebola are not distinct.

Recommendations

Research and development (RD) focusing on Ebola and the Marburg virus should be developed to ensure extensive research on these viruses. This is because the climatic changes taking place worldwide may result in the development of Ebola variants which may lead to outbreaks in the future. However, in the RD area, handling such outbreaks may be easy because of the research conducted in the area. There is also the need to advance the pharmacovigilance system in the regions vulnerable to Ebola and Marburg outbreaks.

References

Baseler, L., Chertow, D., Johnson, K., Feldmann, H., & Morens, D. (2017). The Pathogenesis of Ebola Virus Disease. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease, 12(1), 387-418. Web.

Becker, S., Feldmann, H., Geisbert, T., & Kawaoka, Y. (2018). Marburg and Ebola viruses – marking 50 years since their discovery. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 218(suppl_5), Si-Si. Web.

Bir, M. H., Rahman, T., Das, A., Etu, S. N., Nafiz, I. H., Rakib, A., Mitra, S., Emran, T. B., Dhama, K., Islam, A., Siyadatpanah, A., Mahmud, S., Kim, B. & Hassan, M. M. (2022). Pathogenicity and virulence of Marburg virus. Virulence, 13(1), 609-633. Web.

CDC. (2021). Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease). CDC. Web.

Emanuel, J., Marzi, A., & Feldmann, H. (2018). Filoviruses: Ecology, molecular biology, and evolution. Advances in Virus Research, 189-221. Web.

Feldmann, H., Sprecher, A., & Geisbert, T. (2020). Ebola. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(19), 1832-1842. Web.

Idowu, A., Okafor, I., Oridota, E., & Okwor, T. (2020). Ebola virus disease in the eyes of a rural, agrarian community in Western Nigeria: a mixed method study. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1-9. Web.

Jacob, S. T., Crozier, I., Fischer, W. A., Hewlett, A., Kraft, C. S., Vega, M. D. L., Soka, M. J., Wahl, V., Griffiths, A., Bollinger, L. & Kuhn, J. H. (2020). Ebola virus disease. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 6(1), 1-31. Web.

Kellerborg, K., Brouwer, W., & van Baal, P. (2020). Costs and benefits of early response in the Ebola virus disease outbreak in Sierra Leone. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation, 18(1). Web.

Kidd, L. (2020). Ebola Virus. Web.

Kortepeter, M., Dierberg, K., Shenoy, E., & Cieslak, T. (2020). Marburg virus disease: A summary for clinicians. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 99, 233-242. Web.

Li, W., Chen, W., Li, L., Ji, D., Ji, Y., Li, C., Gao, X., Wang, L., Zhao, M., Duan, X. & Duan, H. (2016). The etiology of Ebola virus disease-like illnesses in Ebola virus negative patients from Sierra Leone. Oncotarget, 7(19), 1-5. Web.

Ndjoyi-Mbiguino, A., Zoa-Assoumou, S., Mourembou, G., & Ennaji, M. (2020). Ebola and Marburg Virus: A Brief Review. Emerging and Reemerging Viral Pathogens, 201-218. Web.

Nyakarahuka, L., Ojwang, J., Tumusiime, A., Balinandi, S., Whitmer, S., Kyazze, S., Kasozi, S., Wetaka, M., Makumbi, I., Dahlke, M., Borchert, J., Lutwama, J., Ströher, U., Rollin, P. E., Nichol, S. T. & Shoemaker, T. R. (2017). Isolated case of Marburg Virus disease, Kampala, Uganda, 2014. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 23(6), 1001-1004.

Nyakarahuka, L., Shoemaker, T. R., Balinandi, S., Chemos, G., Kwesiga, B., Mulei, S., Kyondo, J., Tumusiime, A., Kofman, A., Masiira, B., Whitmer, S., Brown, S., Cannon, D., Chiang, C., Graziano, J., Morales-Betoulle, M., Patel, K., Zufan, S., Komakech, I., Natseri, N., Chepkwurui, P. M., Lubwama, B., Okiria, J., Kayiwa, J., Nkonwa, I. H., Eyu, P., Nakiire, L., Okarikod, E. C., Cheptoyek, L., Wangila, B. E., Wanje, M., Tusiime, P., Bulage, L., Mwebesa, H. G., Ario, A. R., Makumbi, I., Nakinsige, A., Muruta, A., Nanyunja, M., Homsy, J., Zhu, B., Nelson, L., Kaleebu, P., Rollin, P. E., Nichol, S. T., Klena, J. D. And Lutwama, J. J. (2019). Marburg virus disease outbreak in Kween District Uganda, 2017: Epidemiological and laboratory findings. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 13(3), 3-19. Web.

Okonji, O. C., Okonji, E. F., Mohanan, P., Babar, M. S., Saleem, A., Khawaja, U. A., Essar, M. Y. & Hasan, M. M. (2022). Marburg virus disease outbreak amidst COVID-19 in the Republic of Guinea: A point of contention for the fragile health system? Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 13, 1-4. Web.

Okware, S. (2020). Introductory chapter: Emerging challenges in Filovirus control. Emerging Challenges In Filovirus Infections, 1-4. Web.

Patel, P., & Shah, S. (2022). Ebola Virus [Ebook]. Web.

Peterson, A., & Samy, A. (2016). Geographic potential of disease caused by Ebola and Marburg viruses in Africa. Acta Tropica, 162, 114-124. Web.

Ristanović, E., Kokoškov, N., Crozier, I., Kuhn, J., & Gligić, A. (2020). A forgotten episode of Marburg Virus disease: Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 1967. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 84(2), 1-22. Web.

Shifflett, K., & Marzi, A. (2019). Marburg virus pathogenesis – differences and similarities in humans and animal models. Virology Journal, 16(1), 1-12. Web.

Singh, R. K., Dhama, K., Malik, Y. S., Ramakrishnan, M. A., Karthik, K., Khandia, R., Tiwari, R., Munjal, A., Saminathan, M., Sachan, S., Desingu, P. A., Kattoor, J. J., Iqbal, H. M. & Joshi, S. K. (2017). Ebola virus – epidemiology, diagnosis, and control: threat to humans, lessons learnt, and preparedness plans – an update on its 40 year’s journey. Veterinary Quarterly, 37(1), 98-135. Web.

Tuite, A., Watts, A., Khan, K., & Bogoch, I. (2019). Ebola virus outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri provinces, Democratic Republic of Congo, and the potential for further transmission through commercial air travel. Journal of Travel Medicine, 26(7), 2-6. Web.

Yang, J. (2022). Marburg Virus Disease Outbreak in Guinea, August 2021. Global Biosecurity, 4(1), 1-4. Web.