Introduction

In any part of the world practicing Islam, the mosque, regardless of its type remains a typical Islamic edifice. The mosque or masjid in Arabic, offers a worshiping place for the Muslims. Therefore, a mosque is basically “a dedicated room for praying” (Casares and Amarillo 66). While nearly all the required daily litanies can occur anywhere, Muslims men are dictated to go the mosque for Friday prayers. The mosque is the hub of religious activities across the Muslim nation and distinguishes as a leading sacred architecture. Since it is a building where Muslims congregate for prayers, it can have different sizes, ranging from small like those mostly found in villages to large ones found in city environment. Like any other liturgical building, it has a homogeneous collection of components that vary based on the scope of the prayer. It also includes a demarcated opening, partially open and partly roofed, varying in extent, as well as regionally based on the severity of the climate.

In its most evolved form, the mosque has one or numerous minarets, domes, arches, and decorations of Arabic calligraphy and elaborate tracery from the Koran. The progressed forms of the mosques are regarded as some of the deluxe edifices in Islamic architecture. Moreover, it is the sole building type that has been disseminated across the whole Muslim world since the start of Islam in around 610 A.D. According to SLICE in their work Architectural Treasure: The Oldest Mosque of Egypt, the mosque’s elegance not only portray more about the Islamic creed but also the region and period of its establishment. The first mosque was the home of Prophet Muhammad and was located in Medina (Casares and Amarillo 67). It exemplified the Arabians’ house design practiced in the seventh-century coupled with an elegant space bordered by extended rooms and further reinforced by columns. Several mosques constructed in the Arab world adopted this design for many years.

The significance of mosques to the Muslim society is critical owing to the ironic tale behind its establishment. Monotheistic faiths such as Islam initially rejected the notion of constructing a specifically dedicated room for housing prayers. However, the religion has embraced and progressed in terms of mosques architectural designs (Casares and Amarillo 65). The evolved architecture establishes a sense of space that arouses the sanctity of the setting, a feeling of peace and harmony, as well as inducing humbleness among followers during worshiping. These simple and occasionally overlooked architectural styles of mosques hold profound connotations in the religion. The ancient style emphasizes the prominence of the gist of a building over its artistic value. The proposal presents a deepened exhibition of the ancient mosque architecture by detailing the common features while reflecting on how it has evolved to over the period.

Discussion

Philosophically, the entire Earth can be a mosque, and through this norm, namaz shall be complete everywhere conducted. SLICE in their work Architectural Treasure: The Oldest Mosque of Egypt, states that there was no precise edifice to disseminate the spiritual message of Islam. The Muslim Arabs were predominantly nomads with a conservative approach that precludes permanent structures for prayer spaces. Just a square land demarcated by a line was enough for communal prayer. The only requirement was to ensure any side of the drawn square faces Mecca to signify the direction of prayer. However, the design changed where various regions can construct a standards structure for holding prayers (Casares and Amarillo 65). Consequently, the beautification, design, and style transformed, making mosques across the globe now have some shared features such as Sahn, Mihrab, Minaret, Qubba, and occasionally patronage areas as exhibited below.

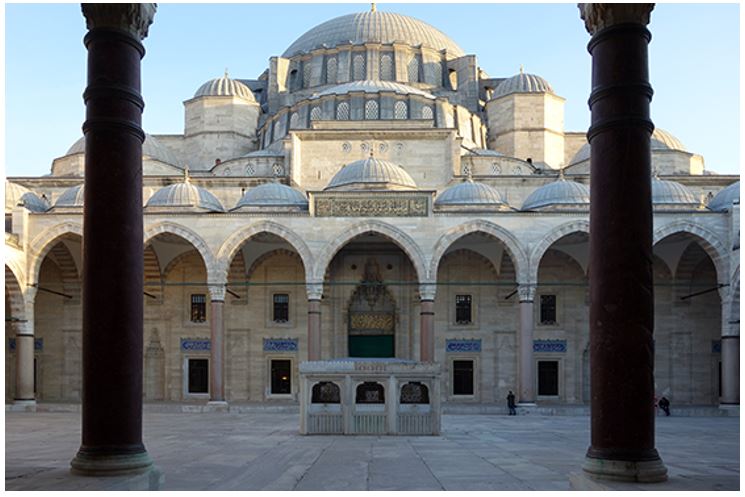

Sahn

Sahn is one of the basic requirements of congregational mosque design. The mosque should seek to be specious to help house a bigger male populace, especially during Friday prayer (Weisbin Para 5). Therefore, it should have a bigger prayer hall, which in many instances, can be attached to the open courtyard (Sahn) (Weisbin Para 5). The courtyard can integrate a fountain and water to help congregations during hot seasons and for ablutions areas.

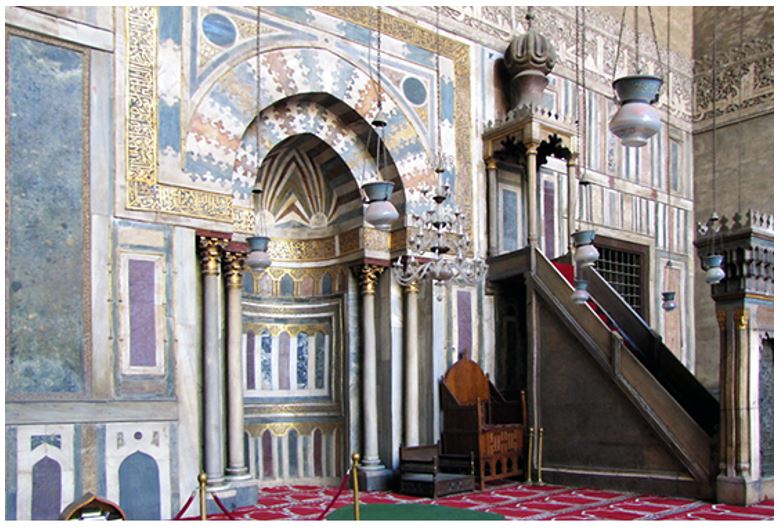

Mihrab

Mihrab is among the vital aspects of the mosque’s architectural plan. It is a niche punctured inside a wall to indicate the position of Mecca for guiding the congregation on where to face when praying (Weisbin Para 6). Mecca, a famous city where Prophet Muhammad was raised, remains an important holy site for the religion. The prayer direction is described as qibla while the section in which mihrab has perforated is the qibla wall. Regardless of the mosque’s location, the niche must face Mecca. For instance, a mosque situated in Egypt has its mihrab pointing the East while those in India face the West.

Minaret (Tower)

Just like the mihrab, minaret is also a key and an extremely observable feature. It is a barbican fixed or placed near the mosque for allowing broadcasting the call of worship (Weisbin Para 7). It assumes numerous forms such as the eminent helix tower of Samara and the elevated, reedy minarets like the one found in Ottoman (Weisbin Para 7). Although not exclusively purposeful, it serves as an influential graphic cue in Islamic manifestation.

Qubba (Dome)

Many mosques have a single or numerous domes or qubba. Although it is not a fundamental feature, qubba carries vast connotations in mosques such as symbolizing the vault of heaven. Its external painting stresses this representation, using the multifaceted geometric, vegetal, or stellate motifs to establish brilliant patterns meant to inspire and awe (Weisbin Para 8). Certain mosques integrate many domes into their designs, while others just include one. For those with just a solitary qubba, it transcends the niche, the most divine segment. Some mosques such as that found in Kairouan, Tunisia incorporate three domes: one right above the qibla wall, another over the minaret, and the other atop the entrance. Since it serves as the geographical compass for worshiping, the qibla hedge, combined with both minbar and mihrab, is lavishly decorated area.

Fittings

Many mosques also embrace other decorative elements as part of its structural designs. For example, a big visual mural or even a pictograph endorsed through bulbous writing repeatedly lingers over the niche. In several instances, the stylish captions are extracts drawn from the Quran, including the edifice’s dedication date as well as the patron’s label. Other essential decorations that have also been included in mosques are the hanging lights. The lamp is a vital aspect because the opening and closing prayer session occur early and late in the day respectively when natural light is not available. Before the advent of electric power, oil lamps were used to bright mosques with where numerous of them being suspended inside to create a glittering spectacle (Weisbin). The soft nimble originating from each lamp helps to underline the calligraphy and other garlands on the surface. Another feature that has been included in a mosque is a carpet.

Patronage and Charitable Institutions

Many ancient mosques were never detached structures but had charitable sections such as schools, hospitals, and kitchens while others also opted to integrate tomb as measure of their multifaceted prestige. Incorporating these helpful institutions reflects essential elements proscribed in the Islamic pillars, calling Muslims to help the needy in society (Weisbin). The assigning of the mosque signifies a devout act by the ruler. The patronage and charitable acts are not merely a generous show but also a resemblance of the architectural sponsorship across many cultures.

Other types of architectural designs in this exhibition include the hypostyle, four-iwan, centrally planned kind, and the contemporary style. First, the hypostyle is the first place where the Muslims prayed, Prophet Muhammad’s house. The style spread across the whole Muslim world. One such key example is The Great Mosque of Kairouan erected in the nineteenth century by Allah Ziyadat (Weisbin). The plan of this mosque as represented in figure 5 shows a big, rectangular design with a hypostyle space and a big interior courtyard. The three echelon tower symbolizes the Syrian bell-minaret and could have initially borrowed from the ancient Roman lighthouses. The architecture also features a series of columns that have significantly defined the hypostyle kind.

The mosque was erected in the previous Byzantine location, and its architects used older construction material such as the columns, a resolution that was powerful and practical based on the Islamic takeover of the Byzantine region. The hypostyle design was also widely applied in the Arab world before the arrival of the four-iwan architecture in the 12th century (Weisbin). Another famous mosque that has adopted the hypostyle plan is Cordoba’s Great Mosque. It has bicolor and two-level arcs, highlighting the dizzying ocular impact of the ancient hypostyle space.

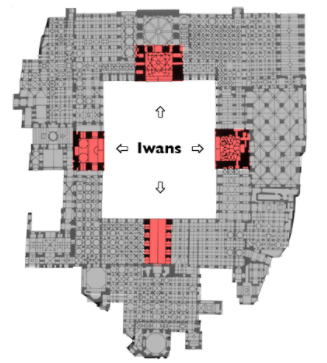

Second, the four-iwan design, just like hypostyle plan that become common during the early Islamic era became prevalent in the 11 century. An iwan is simply a vaulted opening planetary that openly faces the courtyard. The architectural plan emerged during the pre-Islamic period in Iran since it was utilized within imperial and monumental situations. Powerfully linked to the Persian design, the iwan remained an enormous design in the ancient period. Just like the hypostyle plan, the layout in iwan design is planned around the big open courtyard (Weisbin). Nonetheless, in the four-iwan style, every wall in sahn interposed with vast vaulted hall, the iwan. The style has persisted since its inception and spread across many parts of the globe. Moreover, through this kind of plan, the iwan also looks Mecca and is frequently the principal and most lavishly painted part.

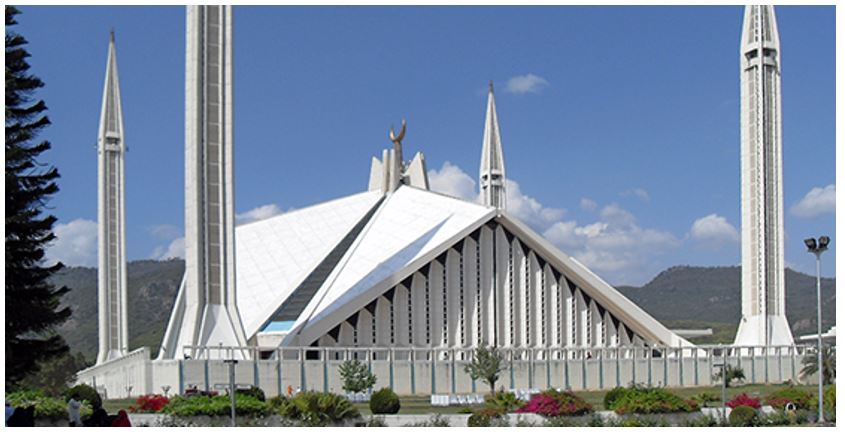

Third, while the four-iwan style was ubiquitous, the Ottoman Empire uniquely embraced the centrally-planned style. The Ottoman planners were powerfully swayed by Sophia Hagia, the utmost of entire Byzantine cathedrals while showing one that shows an immense middle dome above its great nave (Weisbin). Finally, the contemporary mosque plans have integrated and curiously blended drawings and styles from ancient architecture to form something identifiably “Islamic” to fulfill all the design requirements of the communal plan. For instance, King Faisal Mosque in Pakistan blendes traditional forms with contemporary styles combined with pencil–thin minaret.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Islamic architecture depicts an intricate combination of secular and religious styles, beginning the establishment of the religious up to the present-day society. The architecture within the Muslim world, just like the artistic constituent and historic phenomenon, was started within the initial and greatest Caliphate. From these related Islamic cultures and Muslim culture, the mosques confidentially assume the leading role. It is the distillation of the Islamic edifice and provides the sacred site for worship. The proposal has demonstrated deepened exhibition of the prehistoric mosque architecture by describing the collective features and architectural designs to sensitize the latest generational demographics.

While Muslims originally did not have a specific permanent place for praying, mosques evolved in terms of their design and style to include common features such as Sahn, Mihrab, Minaret, Qubba, and occasionally patronage areas. Many mosques also espouse some ornate elements as part of its basic designs. For instance, a giant graphical mural or even a drawing recognized through rounded writing constantly dawdles above the niche. In numerous occurrences, the fashionable headings are excerpts from the Quran, comprising the edifice’s devotion date and the patron’s name. Other kinds of mosques in this architectural display include the hypostyle, four-iwan, centrally planned kind, and the contemporary style.

References

“Architectural Treasure: The Oldest Mosque of Egypt.” YouTube, 2021. Web.

Casares, J, and Amarillo, D. Islamic Heritage Architecture and Art III. WIT Press, 2018.

Weisbin, Kendra. “Introduction to Mosque Architecture.” Smarthistory. n. d. Web.