China

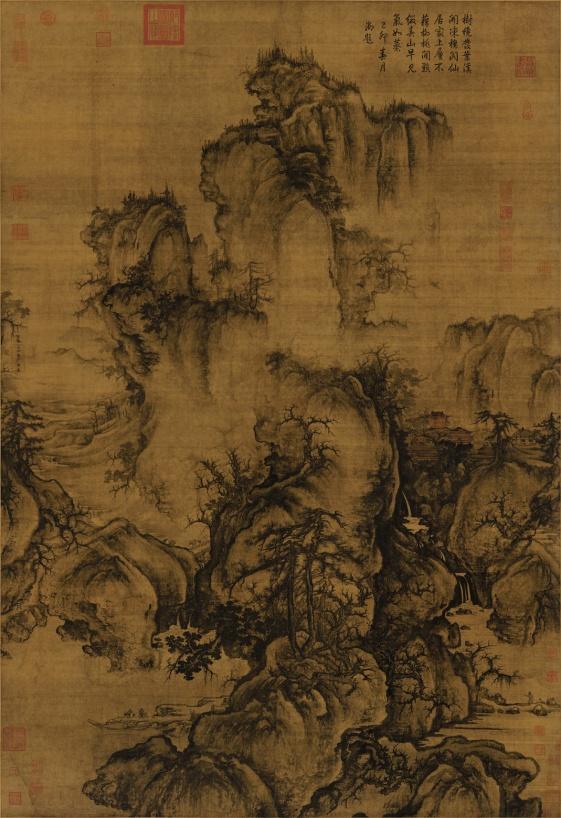

- Name: Guo Xi

- Title: Early Spring (早春圖)

- Date: 1072

- Materials used: hanging scroll, ink, light color, silk

- Current location: National Palace Museum, Taipei

The painting is one of the most famous artworks of Guo Xi. It is an excellent example of the landscape tradition that is common for Chinese art, both prehistoric and modern. Here, Guo Xi uses the method of multiple perspectives known as “the angle of totality” (The University of Washington, n.d.). Such three-dimensional forms, build with strokes, are common for paintings of the Song Dynasty, and therefore were selected for the display.

- Name: Ma Yuan

- Title: Scholar viewing a waterfall (高士觀瀑圖 冊頁 絹本)

- Date: late 12th–early 13th century

- Materials used: album leaf, ink, and color on silk

- Current location: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

“Scholar viewing a waterfall” is another representative of the landscape tradition. This painting is an example of the art created during the Southern Song dynasty (The Metropolitan Museum, n.d.). Chinese art’s uniqueness is in its use of ink (instead of oil) that creates calligraphy-like paintings. Together with the previous piece, the object emphasizes the importance of nature in Chinese art and therefore was chosen for the display.

Japan

- Name: Unknown, Japanese culture

- Title: Fudō Myōō (Achala-vidyārāja)

- Date: 12th century

- Materials used: Wood, traces of color and gold

- Current location: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Fudō Myōō is a Buddhist deity, one of the Kings of Brightness. He uses his sword to overcome ignorance (The Metropolitan Museum, n.d.). The relationship between Japanese culture and Buddhism was not always easy, but the religion itself has still practiced actively in the country and has a significant influence on societal rules. The Japanese culture in this exhibition will be represented through objects dedicated to Buddhism; that is why this object was selected.

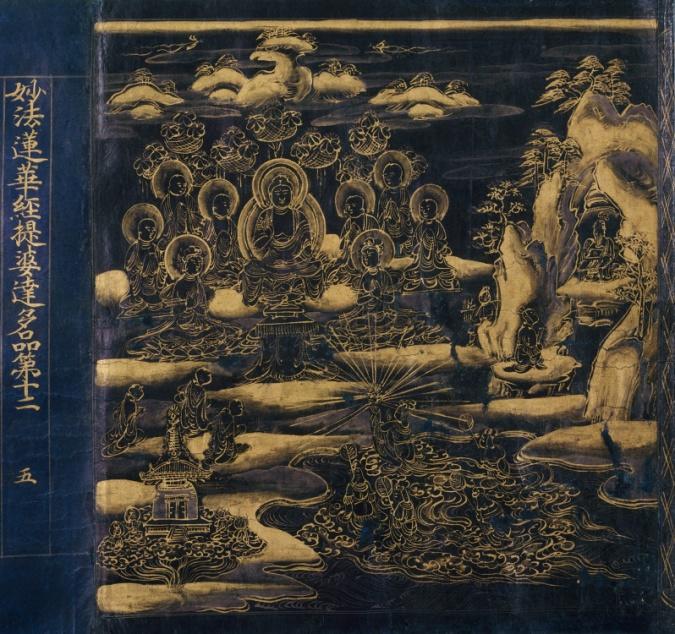

- Name: Unknown, Japanese culture

- Title: “Devadatta,” Chapter 12 of the Lotus Sutra

- Date: 12th century

- Materials used: Handscroll, gold, silver, paper

- Current location: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The object depicts one of the chapters of the Lotus Sutra, one of the Buddhist scriptures. In this chapter, Buddha teaches his followers that anyone can reach enlightenment, a concept essential both for Buddhism and Japanese culture. Handscroll paintings are highly common for Japanese art and usually illustrate narratives. This object was chosen to further emphasize the importance of enlightenment in Japanese art.

Africa

- Name: Unknown, Djenné peoples

- Title: Seated Figure

- Date: 13th century

- Materials used: terracotta (clay)

- Current location: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The seated figure is believed to represent a mourning person. Its pose might show ritual methods of expressing grief overpassed loved ones (The Metropolitan Museum, n.d.). The use of clay and/or other organic materials was common for African art. This and the other object will represent sculptures related to funeral rites.

- Name: Unknown, Tellem peoples

- Title: Vessel: Footed Base

- Date: 13th century

- Materials used: terracotta (clay)

- Current location: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Footed bowls and vessels were not unique for Tellem peoples; they can be found across different African cultures. It is assumed that such bowls were used for funerary purposes only (The Metropolitan Museum, n.d.). Objects made of clay, such as masks, bowls, vessels, were used by African peoples in different rituals but their similarity indicates the mutual influence of peoples on each other. The object is a good example of footed vessels made in West Africa.

The Americas

- Name: Unknown, Maya culture

- Title: Head of a Rain God

- Date: 10-11th century

- Materials used: Fossiliferous limestone

- Current location: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The god of rain was among primary Mesoamerican gods and often depicted with staring large eyes (The Metropolitan Museum, n.d.). Maya’s figure has skeletal features and a beaded headband (Alamy, 2017). Rain God was frequently depicted by different Mesoamerican peoples and highly valued as he was controlling rain, and, therefore, the harvest. The object was chosen as it represents the unique, somewhat ominous, view of the Maya of the Rain God.

- Name: Unknown, Mixtec culture

- Title: Rain God Mask

- Date: 13-14th century

- Materials used: Serpentine

- Current location: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Bared teeth and large, goggle-like eyes are seen in this depiction of Rain God as well. It could be used during funerals or rituals (The Metropolitan Museum, n.d.). This representation of the Rain God has no evident skeletal features. It was selected as a comparison to the Mayan view of the god.

Islam

- Name: Unknown, Uzbekistan culture

- Title: Bowl with Arabic Inscription

- Date: late 10-11th century

- Materials used: Earthenware, glaze

- Current location: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Ceramic bowls with calligraphic inscriptions were standard during that time. These often included aphorisms, advice, or religious references (The Metropolitan Museum, n.d.). Interlacing straps are typical for Islamic art created in Samarkand as they can be seen there on other objects (e.g., architecture) too. The object is a good example of Islamic art that was used daily or could be purchased as a present.

- Name: Unknown, Iranian culture

- Title: Strand of Beads

- Date: 9-12th century

- Materials used: Carnelian

- Current location: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Religious references on everyday objects are seen in this example of Islamic art. Prayer beads have thirty-three or ninety-nine beads used for reciting the names of God. These were not unique to Iran; they represent a substantial layer of Islamic art that still exists (Al Hassani, 2015). This piece of jewelry appears to be modern although it is several decades old and was chosen for the exhibit due to this unique agelessness.

References

Al Hassani, Z. (2015). Muslim prayer beads: What they are and what they are used for. Web.

Alamy. (2017). Head of a Rain God. Web.

The Metropolitan Museum. (n.d.). Timeline history. Web.

The University of Washington. (n.d.). Guo Xi’s Early Spring. Web.