Introduction

When it comes to discussing the discursive significance of Oscar Wilde’s 1895 comedy The Importance of Being Earnest, critics commonly refer to the fact that, despite having been written at the end of the 19th century, the concerned dramaturgic masterpiece continues to enjoy popularity with contemporary audiences. The reason for this is that the play’s themes and motifs resonate well with the archetypal anxieties in people. These, in turn, are predetermined by the socio-cognitive predisposition of the latter as the representatives of the Homo Sapiens species. Hence, the actual key to the play’s literary fame: while being concerned with exploring different aspects of the interrelationship between the representatives of the opposite sexes, The Importance of Being Earnest provides viewers with many in-depth clues as to what this relationship is all about. It also reveals the commonly overlooked psychological qualities of one’s affiliation with the existential virtues of femininity and masculinity. In this paper, the author will aim to substantiate the validity of the above-stated at length while expounding on what should be deemed the discursive implications of the play’s scenes in which its characters indulge in eating and drinking. After all, there is indeed a good reason to deem these scenes suggestive of the actual intricacies of how men and women tend to perceive the surrounding social reality and their place in it.

Analysis/Discussion

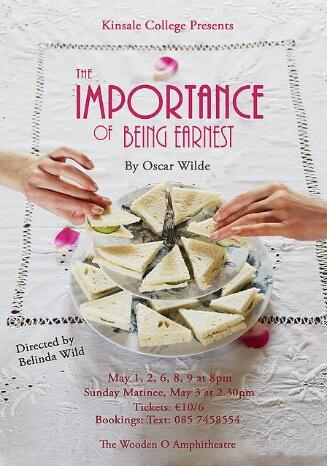

Those who have been exposed to The Importance of Being Earnest, will not be able to overlook the fact that the motif of food consumption does resurface throughout the play’s entirety. This is one of the reasons why this particular play has been commonly referred to as being idiosyncratic, with respect to the author’s personal anxieties about life. Apparently, there is indeed a good rationale for the posters of many modern productions of Wilde’s comedy to contain cucumber sandwiches. The one is seen below (by Wild) represents a perfect example. As one can see, it is not only that the poster radiates a certain “gastronomic” appeal, but there is a notable feminine quality to it as well.

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to assume that the play’s focus on accentuating the physiological aspects of interpersonal communication has the value of a thing-in-itself. Once assessed from the analytical perspective, the comedy’s mentioned feature will appear to be serving a well-defined purpose: to allow the audience to have a better understanding of what accounts for the characters’ psychological makeup. In this regard, Mendelssohn came up with the enlightening observation: “Objects become increasingly important in The Importance

of Being Earnest because language fails to communicate… Because the characters’ desires and behaviors are unspeakable, the characters resort to visual and material signs to articulate the words they cannot” (166). In other words, the “gastronomic” motifs in Wilde’s play are not there to merely amuse viewers, but to convey a certain message of their own.

The scene in which Algernon and Jack are seen exchanging witty remarks over cucumber sandwiches on the table (presumably served for Lady Bracknell and Gwendolen Fairfax), is perfectly illustrative of this suggestion. After all, there appears to be a number of connotative dimensions to it. Probably the most easily identifiable of them has to do with the author’s intention to expose existential attitude, on the part of Algernon, as having been innately hypocritical: “Algernon: Please don’t touch the cucumber sandwiches. They are ordered specially for Aunt Augusta. [Takes one and eats it.] Jack: Well, you have been eating them all the time” (Wilde Act I). This simply could not be otherwise: to be doing something while simultaneously denying another person the right to do the same is exactly what the notion of hypocrisy refers to. Evidently enough, Wilde strived to represent the male characters’ adherence to the provisions of conventional morality as having been rather superficial. The author’s intention, in this respect, appears to correlate well with what many critics believe account for the overall theme of The Importance of Being Earnest: “The main theme of the comedy is the duality of Victorian people, who are earnest and elegant in appearance, but superficial and absurd in nature, and who is wearing the mask of manners and telling lies whenever they like” (Junmei 29). As one can infer from the quoted verbal interexchange, it never even occurred to Algernon that his suggestion did lack a great deal of ethical soundness. The character’s unawareness, in this regard, contributes rather substantially towards ensuring the comedy’s humorous appeal.

Nevertheless, Wilde would not be himself had he not aspired to make sure that there is a strongly defined societal sounding to this appeal. It must be acknowledged that he did succeed in addressing this particular task. The validity of this suggestion can be explored, regarding the initial scene in which Algernon talks to his butler Lane while coming up with the rhetorical question that clearly refers to the lack of moral integrity, on the servant’s part: “Algernon: Why is it that at a bachelor’s establishment the servants invariably drink the champagne? I ask merely for information” (Wilde Act I). Lane handles this question in the way that presupposes the character’s emotional comfortableness with having been caught doing indecent things: “Lane: I attribute it to the superior quality of the wine, sir. I have often observed that in married households the champagne is rarely of a first-rate brand” (Wilde Act I). Clearly enough, the author wanted to capitalize on the audience’s endowment with class-related prejudices, reflective of the Victorian assumption that those of a lower social class are naturally predisposed to lie and steal whenever the opportunity presents itself (Bastiat 54). This, however, is far from having been the author’s only purpose. After all, Lane’s ability to respond to his master’s wits in even withier of a manner spells much doubt on the viability of the Victorian idea that the higher is one’s place on the society’s hierarchical ladder, the more likely would it be for him or her to end up enjoying the reputation of an intellectually advanced person.

As is being suggested by some critics, the significance of the comedy’s food-related motifs should be discussed in conjunction with the strongly patriarchal essence of Victorian society’s outlook on the relationship between men and women. This brings us back to the mentioned “cucumber sandwich” episode in Act I. The reason for this is that, as the conversation between Algernon and Jack reveals, both individuals tend to regard the notion of marriage as being synonymous with the notion of ownership. For example, while trying to discourage Jack from eating any more cucumber sandwiches, Algernon states: “Well, my dear fellow, you need not eat as if you were going to eat it all. You behave as if you were married to her already” (Wilde Act I). What this means is that, for as long as Algernon’s opinion is being concerned, to be married to a woman means to be taking for granted the wife’s function as a “housekeeper”, fully responsible for ensuring that her husband never experiences any shortage of snacks. The male-chauvinistic essence of such an assumption is apparent.

It is understood, of course, that a woman’s role as a housewife presupposes a certain intellectual mediocrity, on her part. This is how it used to be seen during the Victorian era (Garland 275). In this turn, this helps to explain why Algernon could not think of any better way of explaining the absence of cucumber sandwiches to Lady Bracknell and Gwendolen, but to lie to them about it in the most blatant manner possible, with Lane being ready to play along: “Algernon: Good heavens! Lane! Why are there no cucumber sandwiches? I ordered them specially. Lane: There were no cucumbers in the market this morning, sir. I went down twice” (Wilde Act I). Nevertheless, despite the obviously fraudulent nature of Lane’s claim, both women seem to take it representing an undisputed truth-value. Because of it, one will be naturally driven to assume that The Importance of Being Earnest was intended to strengthen the male-chauvinistic stereotypes about women, in general, and women’s cognitive abilities, in particular.

There is, however, much more to the issue than it may appear initially. As Bastiat argued: “The play makes extensive reference both implicitly and explicitly to the debate (about women’s inferiority)… at the same time it resists the traditional notions that govern men’s and women’s lives and supports equality between the sexes” (59). Once again, the motif of food consumption comes in very handy for the author. After having realized that Cecily was able to learn the truth about his actual identity, Algernon becomes very agitated and this, in turn, causes him to begin devouring muffins (served at Jack’s country estate) one after another as if there was no tomorrow. While exposed to the spectacle, Jack cannot help expressing his displeasure with what he sees. To this, Algernon replies that eating muffins is his way of coping with stress: “When I am in trouble, eating is the only thing that consoles me. Indeed, when I am in really great trouble, as anyone who knows me intimately will tell you, I refuse everything except food and drink” (Wilde Act II). The way in which Algernon handles his friend’s remark is suggestive of this character’s deep-seated affiliation with what has been traditionally deemed as a “womanly” approach to addressing life challenges: becoming hysterical and consequently quite incapable of taking full advantage of its endowment with the sense of rationale (Balkin 32).

Hence, the scene’s actual message to the viewing audience: being a man, in the physiological sense of this word, does not necessarily mean being psychologically comfortable with the socially constructed paradigm of masculinity. According to Nassar, both characters are strongly effeminate, which explains their preoccupation with trying to look fashionable and the nature of their intellectual wits (79). In this regard, the female characters of Gwendolyn and Cecily appear to be much different. It is the truth that each of them has its own “womanly twinks”, such as the characters’ tendency to live in the phantasy world and their psychological predisposition towards idealizing seriousness in men. At the same time, however, Gwendolyn and Cecily are represented as being fully capable of indulging in the logical/cause-effect type of reasoning: something that has traditionally been considered an exclusively masculine virtue (Peltason 125). While answering Gwendolyn’s question as to what Jack and Algernon have been up to, following their confession of having intentionally misled both women as to their true identity, Cecily states: “They have been eating muffins. That looks like repentance” (Wilde Act III). Such Cecily’s suggestion betrays her of having been a rationally-minded individual who believed that the behavioral extrapolations of one’s existential self-identity are invariably anchored in what happened to be his or her gender. Both women simply could not bring themselves to think that there could have been anything irrational about the mentioned “muffin devouring” spectacle, on Algernon’s part.

Hence, yet another important idea that defines the comedy’s overall discursive sounding: the physiological particulars of one’s affiliation with either of the two opposite sexes, has only a minor effect on the actual workings of his or her psyche. This idea can be generally referred to as that of “gender exchangeability”. For example, despite the feminine looks of Cecily, there are many masculine qualities to how she addresses different challenges and forms her opinions of things (Bastiat 55). Essentially the same can be said about the character of Gwendolyn. Just as is being the case with Cecily, Gwendolyn makes a point in refusing to live up to the Victorian ideal of a woman as a “sweet darling”, whose psychological leanings closely remind that of a child. Such her tendency is reflective of Gwendolyn’s refusal to drink tea with too much sugar in it: “You (Miss Cardew) have filled my tea with lumps of sugar, and though I asked most distinctly for bread and butter, you have given me cake” (Wilde Act II). As one can infer from the comedy, Gwendolyn’s dislike of sweets had a rational quality to it: the character used to find it very insulting that most people were driven to assume that she had a “tooth” for sweet tea and candies.

This once again points out the fact that there is much more to the comedy’s exploration of different food-related themes and motifs than it may seem at first glance. Even though The Importance of Being Earnest was written before the term “psychology” came into being, its author was nevertheless able to prove himself as someone full of psychological insights into the essence of human cognition. In particular, Wilde has shown that for a particular play to enjoy popularity with the audience, it must appeal to the unconscious instincts in the former (Cohn 184). One of such instincts is explicitly “nutritional”. That is, along with aspiring to succeed in sexual mating and imposing dominance on others, people apply much effort in making sure they have plenty of food. Therefore, the literary themes and motifs that draw on food and the specifics of how individuals go about consuming it, are bound to be found appealing by the audience. This should especially be the case when the mentioned themes are closely interconnected with the sex and dominance-related ones: just as it is seen in The Importance of Being Earnest.

Conclusion

In light of what has been said earlier, it will be appropriate to confirm the viability of the paper’s initial thesis: there is a strong archetypal quality to The Importance of Being Earnest, in general, and the comedy’s themes/motifs, in particular. Throughout the comedy, the author masterfully explores the deep-seated dichotomy between one’s ability to indulge in rational thinking and the person’s tendency to utilize this ability as a part of advancing its biological agenda. This contributes more than anything towards ensuring the psychological plausibility of the plot’s twists. For as long as the author’s exploration of the food-related themes/motifs is being concerned, it serves the purpose of exposing the superficiality of what later came to be known as “Victorian morality”.

There can be very little doubt that Wilde’s comedy did contribute towards undermining it. Wilde’s scandalous reputation and the fact his play used to be ostracized on account of its presumed “immorality” are the best proofs that this indeed has been the case. Evidently enough, The Importance of Being Earnest has not been conceived to merely entertain, but also to educate the audience about what kind of invisible forces play a role in defining one’s attitudes in life, as well as the person’s stance on the issues of social importance. Therefore, it will be appropriate to conclude this paper by stressing out once again that the key to the comedy’s popularity is both its engagement with the matters of the unconscious and the progressive sounding of its themes and motifs: something that has been hypothesized initially.

Works Cited

Balkin, Sarah. “Realizing Personality in The Importance of Being Earnest.” Modern Drama, vol. 59, no. 1, 2016, pp. 26-40.

Bastiat, Brigitte. “The Importance of Being Earnest (1895) by Oscar Wilde: Conformity and Resistance in Victorian Society.” Cahiers Victoriens & Édouardiens, vol. 5, no. 72, 2010, pp. 53-63.

Cohn, Elisha. “’One Single Ivory Cell’: Oscar Wilde and the Brain.” Journal of Victorian Culture, vol. 17, no. 2, 2012, pp. 183-205.

Garland, Tony. “The Contest of Naming Between Ladies in The Importance of Being Earnest.” The Explicator, vol. 70, no. 4, 2012, pp. 272–280.

Junmei, Jiang. “A Corpus-Aided Study of Language Features of ‘The Importance of Being Earnest’.” I-Manager’s Journal on English Language Teaching, vol. 7, no. 2, 2017, pp. 29-38.

Mendelssohn, Michèle. Henry James, Oscar Wilde and Aesthetic Culture. Edinburgh University Press, 2007.

Nassaar, Christopher. “Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.” The Explicator, vol. 60, no. 2, 2002, pp. 78-80.

Peltason, Timothy. “Oscar in Earnest.” Raritan, vol. 35, no. 1, 2015, pp. 114-144.

Wild, Belinda. “The Importance of Being Earnest Production Poster.” Kinsale College, 2015, Web.

Wilde, Oscar. “The Importance of Being Earnest.” The Project Gutenberg eBook, Web.