Introduction

“Heaven, Hell, and Dying Well: Images of Death in the Middle Ages” is an art exhibit presented by the J. Paul Getty Museum in 2012. The exhibit revolves around the topic of death, the afterlife, and their perception by artists of the 15th century. Comprised of nearly 20 artworks of different authors, the collection mostly contains paintings on paper and parchment, including also the photo of the cathedral’s facade and an example of a funerary sculpture.

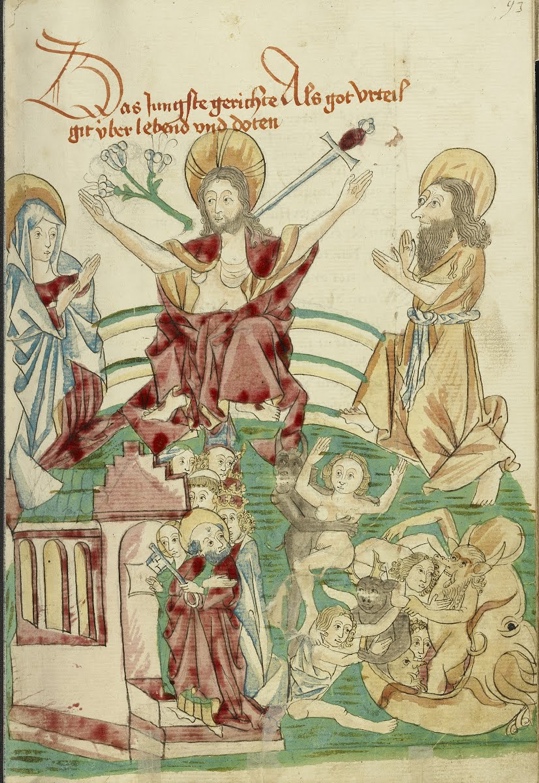

The Last Judgement by Follower of Hans Schilling, 1469

Figure 1 depicts one of the paintings belonging to the art collection dedicated to the medieval depictions of life and death (J. Paul Getty Museum). The Last Judgment, created in the middle of the 15th century, is a painting characterized by the wide use of primary colors, empty negative space, reversed perspective, and contour lines to divide two major scenes: rainbow and the gates to Heaven and Hell (DeWitte et al. 45). Well-defined contour lines are used to depict the visual image of God and fellow humans. In most cases, the shapes are organic and resemble the outline of people and inhumane objects. However, the two objects, a flower and a sword are depicted with the help of approximate geometric shapes.

One of the most interesting aspects of the painting is the reversed depth of the image. The contour lines for the rainbow served to divide God from finite humans, making God closer and more distinct than all the humans. Moreover, the space above the rainbow is negative, whereas the gateway scene is painted on the green landscape. The painting includes much white space, including the depiction of people. The primary color of red unites God and people awaiting their pathway to Heaven, whereas sinners are painted with no clothing and color. The whole painting is created using the tones of three primary colors and the secondary color of green. The mass of the second half of the painting leaves no free space, as it is consumed by color and shapes, whereas the scene of the heavens has much unused space.

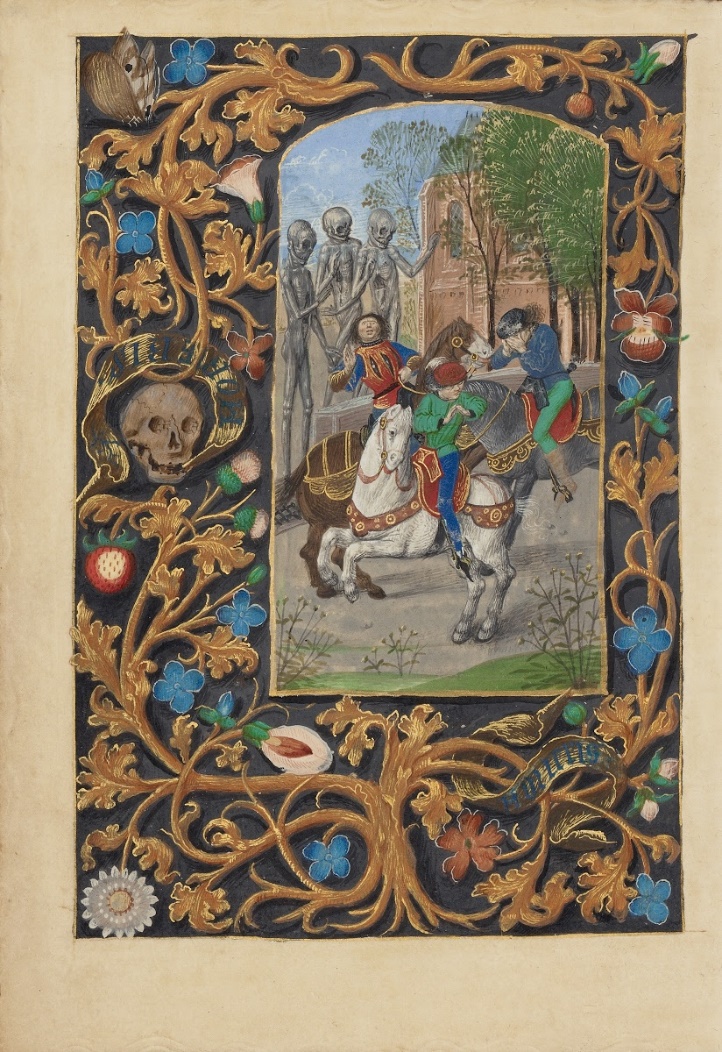

The Three Living and The Three Dead by the Master of the. Dresden Prayerbook, c. 1480

The second painting from the collection depicts the “image-within-image” scene of three horse riders faced with the ghosts of their ancestors. The distinct feature of this artwork is the division between the scene and the ornament. The scene is divided by the golden contour lines, creating a golden embroidered frame with skeletons hiding behind golden, red, and blue flowers. The image in the center, as one can see in Figure 2, has no unused space on the canvas, and the three-dimensional volume is specified by the state of motion among the riders. The volume is also implied with the help of white lines and touches on the objects. The color palette of the central image varies between cool primary and secondary colors, such as green and blue and green shades of the skeletons in the background. The contrast between the bright colors depicting the riders and the single grey shade of the skeletons serves as a ground for life-death comparison.

As far as the second part of the painting is concerned, the negative black space of the image provides it with a higher volume compared to the central scene. The outline of the golden organic shapes makes the picture look like a three-dimensional artwork. The color palette, while generally similar to the central scene, is prevailed with gold and dark shades that add to the mass of the painting. The skeleton patterns in both scenes create a rhythm and a repetitive theme of death throughout the image, connecting the two parts of the painting.

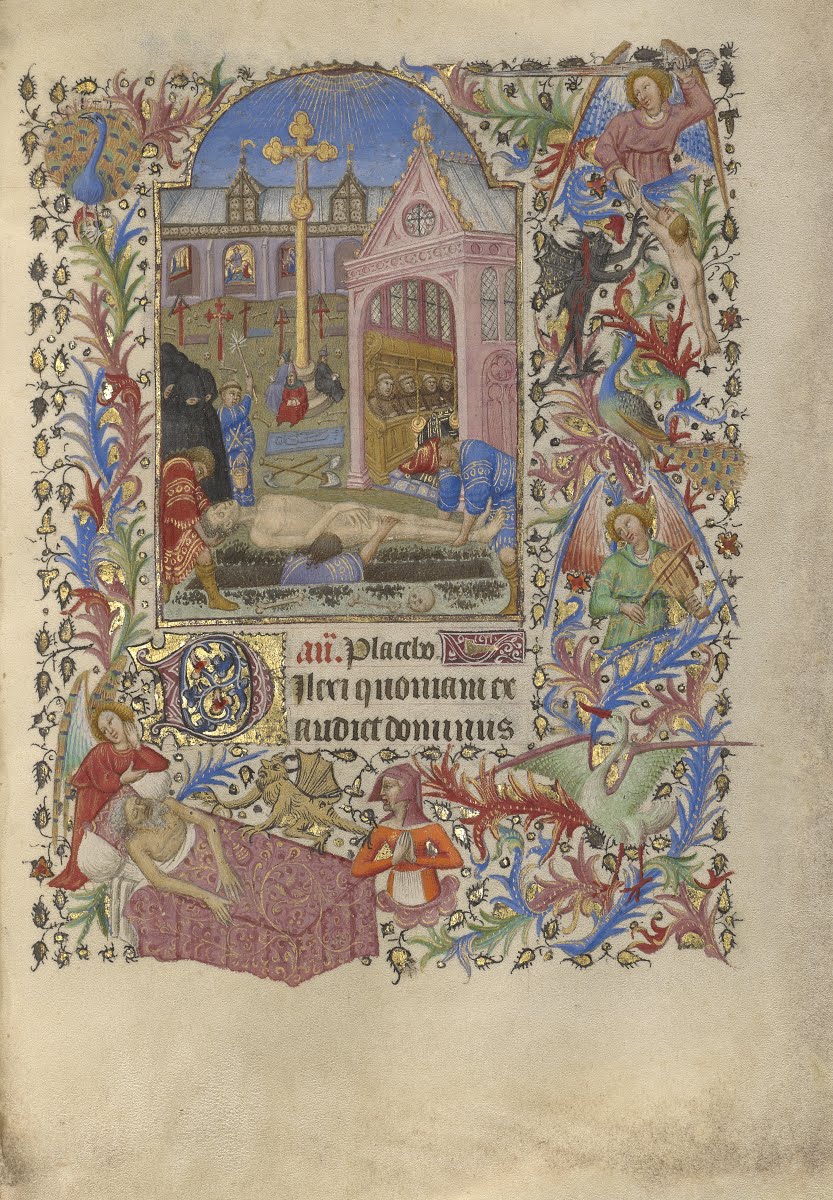

A Burial by Spitz Master, c. 1420

Similar to The Three Dead and The Three Living, A Burial is a painting divided into two sceneries with the help of contour lines that create a window-like shape. Within this shape, there is no free space, with the negative space portrayed as the landscape. The central scene demonstrates the depth of the image, as it presents both the foreground of the funeral and the background full of details such as the chapel and the cemetery. The perspective is especially vivid in the portrayal of the chapel, as one can see how implied lines are directed towards a single dot on the canvas.

Most action, however, takes place outside the window-like shape, as it depicts the scenes of angels and demons fighting for one’s life after death. Although there is much negative space in the picture, there are many shapes and details. The painting is full of implied lines created with the help of floral prints, creating a golden, blue, and red floral pattern throughout the image. Furthermore, the image includes a consistent rhythm of angels who have the same facial features and outline, manifesting the topic of the afterlife. Another imagery pattern is the depiction of the dead body, connecting both pieces of the painting through the image of a single man, whose death is portrayed both on earth and in the afterlife. The painting is a combination of both geometric and organic shapes, but the latter tends to prevail.

Conclusion

Despite a rather biased perception of medieval art, this art collection has helped me take a fresh, more attentive look at the culture of the 15th century. I frankly enjoyed every exhibit due to the surreal nature of the paintings. While having completely different motifs and themes at times, these paintings share a variety of common features: frames and ornaments, a contrastive color palette, the use of various tones of red to depict Godly creatures, and blue to depict a heavenly nature of something. This collection serves as evidence of a successful combination of the objective portrayal of reality and surreal perception of the human soul.

Works Cited

DeWitte, Debra J. et al. Gateways to Art: Understanding the Visual Arts (Third Edition). London, United Kingdom: Thames & Hudson.

The J. Paul Getty Museum. “Heaven, Hell, and Dying Well.” Google Arts & Culture, Web.