Introduction

The history of the Impressionist movement would not have been complete without the name of Mary Cassatt. She was born in America but moved to Paris to study art and stayed there for life. She is known as a painter, draftsman, and printmaker. Still, she owes her popularity to portraits of women and mothers with children, which depict daily life in typically domestic settings. Her works are frequently treated in the feminist contexts as such that reflect the ideas of feminism and have a significant impact on the development of this movement at present. Nevertheless, Cassatt’s paintings depicting mothers with children are likely to speak about the social status of women rather than represent a new feminist ideal.

Life and Work of Mary Cassatt

Mary Cassatt, one of the first impressionists and, probably, the only female representative of this direction in art, was born in 1844 in Pennsylvania. She was born in a big family with seven children. Her parent believed that travel was an important part of education, and the girl spend five years in Europe where she took first lessons in music and drawing. Even though her family did not support her decision to become an artist, Mary Cassatt went to study painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. She differed from her fellow students many of whom were looking for recognition by her strong desire to become a professional artist.

Cassatt lived and worked at the time when females were mainly defined by their ability to have children. In fact, motherhood was integral to the patriarchal family model and was treated as “the virtuous norm for the respectable woman.” Moreover, education was considered to be a tool that contributed to better performance of duties as a wife or a mother. Still, it was probably not a model she wanted to follow.

In 1866, Cassatt finished her studies in America and moved to Paris to continue artistic education. Even though she could not study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Mary took private lessons with outstanding masters and trained by copying the paintings in Louvre. At that time, one of her first known drawings, A Mandoline Player, was accepted for the Paris Salon, which was a success for the young artist.

Cassatt went back to the United States in 1870 to return to Europe a year later and face some brighter perspectives. One of her paintings, Two Women Throwing Flowers during Carnival, was included in the exhibition of the Salon of 1872. Moreover, it was purchased, and the artistic society started talking about Mary Cassatt. Later, she joined impressionists and became the only female impressionist writer. Nevertheless, the artist obtained her reputation and fame for the series of paintings depicting a mother and a child.

Images of Mother and Child – A New Feminist Ideal or Representation of Social Status?

On the whole, the subject of Mother and a child is one of the oldest in the history of art. Nevertheless, in the end of the 19th century, this concept lost its traditional religious and historical aspects and developed into a study of Modern Motherhood. The change in defining this concept was to a large extent stimulated by the works of four female artists such as Berthe Morisot (1841-95), Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907), and Kithe Kollwitz (1867-1945).

Despite the fact that they worked independently and their approaches were individual, all of them focused on the issue of the increasing intimacy between mothers and children. This similarity can be justified by changes that were happening in childrearing practices of that time. Moreover, attitudes toward motherhood obtained some romantic features. The image of the mother and child roots back to the times of predynastic Egypt. Later, it developed during Renaissance whet the depiction of Madonna and Child was typical for many artists.

Mary Cassatt is sometimes characterized as a strong and ambitious woman. Some researchers consider that works of art by Mary Cassatt challenge inauthentic or stereotypic images of women. On the one hand, such treatment of her works relates them to feministic ideas since it is considered that the artist thought women were complete within themselves. Still, it is an arguable position because Cassatt was far from the implications of feminist theory.

Her paintings of women without children are fewer and usually depict ladies involved in some daily activities such as gathering fruit, for example. Moreover, there are no images of females doing something not typical of women of that time. Consequently, the role of a new feminist ideal that is sometimes attributed to the name of Mary Cassatt is not justified because the paintings that made her popular have a different meaning.

Paintings depicting a mother and a child have a unique place in the heritage of Mary Cassatt. She was praised by the critics of her time for these pictures. Thus, it was considered that the mother and child are the touchstone of the artist’s inspiration. The subject of a woman and a child is persistent in the work of the artist. One of the popular paintings, Breakfast in Bed, shows the particular treatment of this subject by Cassatt (See Figure 1).

Looking at the painting, the spectator sees the child in the center of the composition sitting on the bed. The plot itself is a quiet morning moment of a mother embracing her daughter, while the little girl is looking elsewhere trying to find something interesting. Although the mother looks relaxed, her arms are protecting her baby and her eyes follow the girl’s curious look. The painter depicts a simple daily moment which, however, contributes to the relationships of a mother and a child.

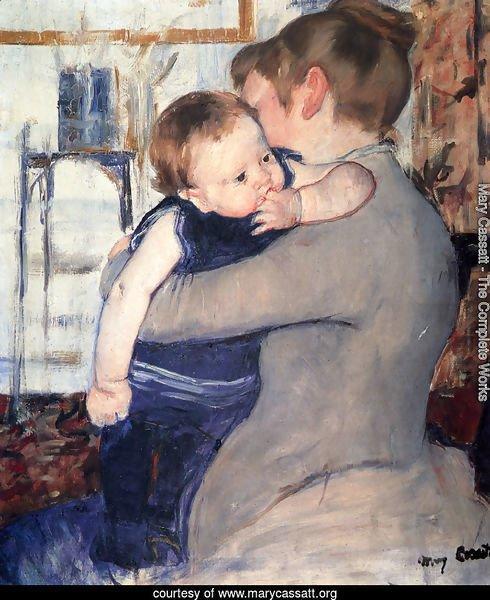

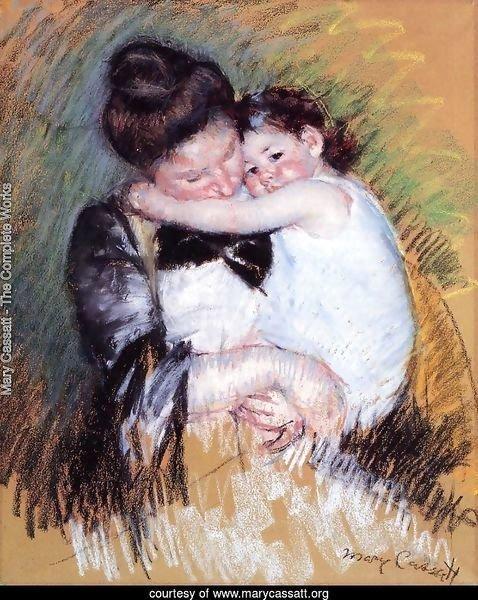

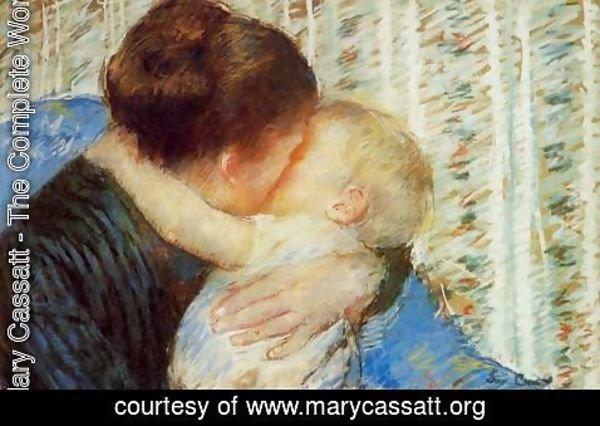

Cassatt’s works have their recognizable style and certain peculiarities that distinguish them among the others. One of the issues that should be mentioned is the lack of integrity of the individual body, which is replaced by merged bodies. In most of her works, the bodies of a mother and a child have their own boundaries or their own space. Nevertheless, both figures depicted in Cassatt’s works share a border. These paintings with two figures turned into one shape provide the impression of unity. The explanation for the use of this composition is that mothers frequently embrace young children (See Figures 2, 3, and 4). In fact, the painter represents her visual concept of maternity, which she percepts as a physical bond, which is typical of mothers and babies.

As it was already mentioned, the pictures of Cassatt are full of embraces. The painter pays no attention to background, which is extraneous to the figures of mother and child. Both mother and child look mutually absorbed and never look at anyone or anything but at each other. Absence of any objects of the outside world as the background allows concentrating on the main images. Mary Cassatt paints bodies caress, kisses, hugs, and strokes.

Cassatt’s works were characterized as those showing a mother and child whose intimate, irrevocable bond “unites these beings; they exist mutually. The expressions of their faces are associated, the one with the other. What Miss Cassatt has sought in woman is not so much her delicate grace, flower of fugitive bloom, as that austere part of her, ennobled by mater.” On the whole, the composition as well as plots of paintings depicting the mother and child unite to deliver the significance of motherhood not as a destiny, but as a source of positive emotions.

Conclusion

Summarizing, it should be mentioned that the works of Mary Cassatt occupy a particular place in the history of art. They attract attention to tender relations of a mother and a child and create a new idea of motherhood. Her paintings rather depict relationships than images themselves. Critics agree that the spectators tend to enjoy Cassatt’s children due to the fact that their mothers enjoy them and it is evident from the pictures.

Probably, her life and career can be a source of inspiration for feminists, but her artistic works depicting a mother and a child are the embodiment of motherhood not as the major destination of a woman in a patriarchal society, but as a great happiness and joy. Therefore, her depictions of the mother and child are more likely to represent motherhood as a social status of a woman rather than serve as a new feminist ideal.

Bibliography

“Biography of Mary Cassatt.” Mary Cassatt. 2018. Web.

Breakfast in Bed. Digital image. Huntington. Web.

Broude, Norma. “Mary Cassatt: Modern Woman or the Cult of True Womanhood?” Woman’s Art Journal 21, no. 2 (2000): 36-43. Web.

Buettner, Stewart. “Images of Modern Motherhood in the Art of Morisot, Cassatt, Modersohn-Becker, Kollwitz.” Woman’s Art Journal 7, no. 2 (1986): 14-21. Web.

Caldwell, Eleanor B. “Exposition Mary Cassatt. Gallery Durandruel, Paris. MDCCCXCIII.” Modern Art 3, no. 1 (1895): 4-2. Web.

Greer, Germaine. “Storm in the Teacups.” The Guardian, 2006. Web.

Mathews, Nancy Mowll. “The Greatest Woman Painter”: Cecilia Beaux, Mary Cassatt, and Issues of Female Fame.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 124, no. 3 (2000): 293-316. Web.

MacKinnon, Catharine A. “Feminism, Marxism, Method, and the State: An Agenda for Theory.” Signs 7, no. 3 (1982): 515-44. Web.

Mother and Child. Digital image. Mary Cassatt. Web.

Mother and Child 2. Digital image. Mary Cassatt. Web.

Mother and Child 7. Digital image. Mary Cassatt. Web.

Yeh, Susan Fillin. “Mary Cassatt’s Images of Women.” Art Journal 35, no. 4 (1976): 359-63. Web.