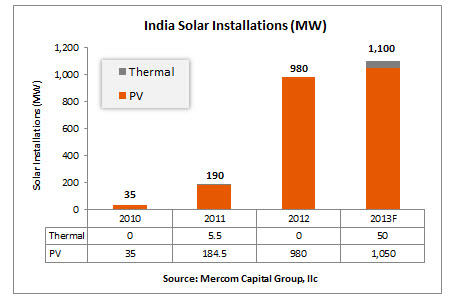

The Indian solar installation program has slowed down year-after-year according to Mercom Capital Group. The consultancy and communication firm had predicted the installations to reach 1,000 MW by the end of this year. Between 2012 and 2013, solar installations in India increased by 12 MW; so elusive was the growth that the firm’s comprehensive survey had to identify numerous factors that had caused the slow solar growth (Sengupta n.pag).

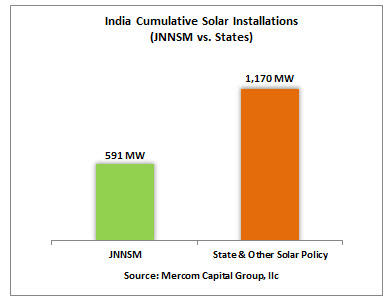

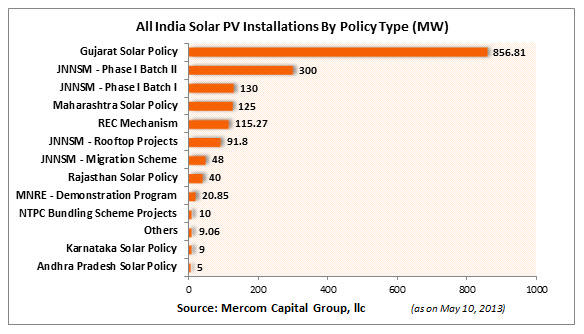

For instance, the delay in the Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission (JNNSM) PV projects to go online contributed to the slow pace of solar installation in India. JNNSM PV projects to be offline until June 2015. In addition, the failure of Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) projects in India, as well as the current trade disputes pitting the US and India in the WTO have played a part in the delayed solar installations.

Concentrating Solar Power is one of the best sustainable options of acquiring energy from sun rays using clean mirrors placed at specific angles in hot regions of the world. From the point of no greenhouse emissions and the possibility of producing cheap electricity, CSP is not only environmentally friendly by protecting the global climate, but also economically sustainable.

Fossil fuels energy remains the major emitter of CO2 into the environment; it also uses non-recyclable products as opposed to CSP, which uses inexhaustible sunlight rays and recyclable parabolic mirrors.

The US claims that the Domestic Content Requirement (DCR) regulations discriminate against their solar cells in moving to inculcate thin-film technology (Prabhu par. 3) has also been a factor for the slow pace of solar installation. The constantly escalating prices of diesel, the Indian population is in dire need of cheap and environmentally friendly power.

Apart from the reduction in project margins that emanate from reverse auctions, government agencies have also delayed crucial state policies that address the installation of solar panels. For instance, the enforcement of real Renewable Purchase Obligation (RPO) has taken different twists, thus making it difficult for steady implementation of the solar projects.

Even though India’s economy is growing at a slow pace, Mercom asserted that the country’s solar market is still unexploited. In a move to counter the slow process of solar installation and constant power shortages, the government, on January 2013, deregulated diesel prices by increasing its price by Rs 0.50 per month for retail customers (Sengupta n.pag). As a consequence, the solar situation has slowed industrial growth. Moreover, generating power through a backup system has become a costly alternative.

Tentatively, the government of India is attempting to import subsidized diesel to serve the needy market. Notably, the past 13 months have seen the prices of diesel increased by 15%; solar, therefore, has become a very attractive alternative. Agriculture, businesses, and industries are hugely affected by power shortages; the government should put in place and implement relevant policy objectives in order to increase the growth of solar installation all over the country.

For the second time, India has delayed the solar bid cut-off date; this unexpected occurrence was a major concern among investors in the country, as well as among solar designers. Based on the delays that have been witnessed in the first phase of JNNSM, the 2022 expectation of solar installation of 20GW is highly likely not to meet its deadline (Peschel par. 6).

The government moves to assure the citizens of its commitment to completely roll out the solar projects by allowing the lowest bidders for the projects to win the tenders has received mass criticism. Critics argue that such a move would result in “bad competition and bad projects” since most bidders may only target the 30% cover-up cost for a project from ‘viability gap funding’ (VGF) (Sengupta n.pag).

The situation is likely to pressurize solar developers to bid for the projects, as there is no alternative source of funding. Ritesh Pothan, a solar consultant in India, adds that the bidding and auctioning processes would create cheap solar projects.

The future of solar projects is not as bleak as other pundits may believe; the signing of the purchase agreements for NSM phase II batch one is likely to occur in April 2014 given that its allocation process was cleared by early parts of March. Considering the disappointments in the market in 2013 following the slow pace of installation, the government of India has to come up with clear, simple, and friendly project policies so that the evolving solar market experiences high growth rate than countries like Japan and China.

Recent commitments by government agencies and environmental organizations could see CSP provide 7% of usable power by 2022 (Peschel par. 9). In encouraging CSP, the government of India should offer investment incentives and tax holidays to firms that intend to set-up such environmental projects.

This move, coupled with improved operations, research, and development and competition among firms, lower the generation and supply cost of solar power. Even though a CSP plant requires high initial cost, the cost-benefit analysis of the project from a long-term perspective reveals cheap operational cost, albeit constant generation of electricity.

The reverse auctions that the government had proposed in the bidding process hinder the economic viability of the project. Therefore, India has to strive to “look better and better every day” by implementing relevant policies that work towards solving the rampant power shortage among millions of Indians. The Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) should avoid continuous delays in the solar projects to enable India to be at par with the whole world in the implementation of clean sources of energy.

Works Cited

Peschel, T. India’s National Solar Mission to miss capacity targets. 2014. Web.

Prabhu, R. Indian Solar Market Update – 2nd Quarter 2013. Web.

Sengupta, D. “Indian solar installations are forecast to be approximately 1,000 MW.” The Economic Times [Mumbai] 2014: n. pag. Web.