Nowadays, Buddhism is one of the major religions in the world and is practiced by diverse communities across countries and continents. The active spread of Buddhism from India, where it originated, to other countries, happened primarily through the network of Silk Roads. These trade routes played a significant role in the development of ancient civilizations as they allowed the exchange of not only material goods but also ideas and cultural values. However, there was one more important factor that accelerated this process. It was the political environment in the Mauryan Empire (324-185 BC) promoted by King Asoka. His commitment to Buddha’s Four Noble Truths and the encouragement of missionary work substantially facilitated the transmission of Buddhism to distant states. Considering this, the present paper will discuss the role of Asoka in the dissemination of Buddhism. It will show how the success of his missionary work was supported by the system of well-developed trade routes that connected the Mauryan Empire with civilizations and societies across Asia.

The History and Practice of Buddhism: Brief Overview

The practice of Buddhism as it is known today includes practices aimed at the development of mindfulness. According to Aich (2013), mindfulness is “a kind of meditation (vipassana) involving an acceptance of thoughts and perceptions, a ‘bare attention’ to these events without attachment” (S167). It is considered that by doing meditation, one can realize the Four Noble Truths, which were first coined by Siddhartha or Gautama Buddha around the 5th-6th century BC, and attain equanimity and enlightenment (Aich 2013). Thus, Buddhism is very different from many monotheistic religions as it emphasizes the role of an individual in his or her own salvation. Besides, it suggests that people from any demographic, social, and cultural background can attain enlightenment. Therefore, at first, the Buddhist teaching was not very popular in ancient India, where the cast system and Hinduism were of great cultural importance (“The History of Buddhism” n.d.). Besides, during the life of Siddhartha, Buddhism was closely linked to monasticism and promoted the rejection of worldly possessions (“The History of Buddhism” n.d.). Thus, for many people who had families and were involved in daily work and commercial activities, it was difficult to devote themselves to Buddhism.

The situation had changed when the initial Buddhist tradition evolved into Mahayana Buddhism. This form of religious practice suggests that everyone can “still attain enlightenment by performing acts of devotion or performing the duties of their jobs” (“The History of Buddhism,” n.d., par. 7). In this way, Buddhism became more flexible, secular, and inclusive. However, the major push in the promotion of this religion in both India and outside was due to the support of the Buddhist teaching by King Asoka. The following section will focus on the discussion of factors that contributed to his adoption of Buddhism and its establishment as the main religion in the empire.

King Asoka’s Politics

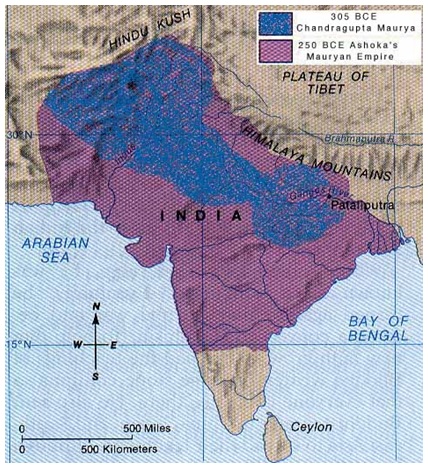

King Asoka was the third ruler in the Mauryan Empire (324-185 BC), which occupied a large territory of the Indian subcontinent (Figure 1). Those territories were taken up primarily as a result of aggressive expansion policies that were implemented by both King Asoka and his predecessors, Chandragupta Maurya (324-300 BC) and Bindusara (300-272 BC) (Chakravarti 2015). As Figure 1 demonstrates, the territory of the empire had grown significantly since the reign of the first Mauryan king and attained its maximum expansion under the rule of Asoka. It means that the kings of the empire frequently engaged in conquests of new lands. Noteworthily, it was after one of such military endeavors when Asoka decided to undertake a more peaceful and non-violent approach to politics.

The subjugation of Kalinga became one of the most important events in Asoka’s reign. However, instead of celebrating the defeat of the kingdom that withstand the Mauryan expansion for a long time, the king started to feel bitter after the realization of the devastating consequences of the fight for the new territory (Kulke and Rothermund 2004). Kulke and Rothermund (2004) mention that as a result of the war, “150,000 people were forcibly abducted from their homes, 100,000 were killed in battle and many more died later on” (66). Although Asoka did not show an intention to return the status of independence to Kalinga, he became overwhelmed by these numbers and then found consolation in the spiritual search (Kulke and Rothermund 2004). In this way, he became a passionate Buddhist devotee and started to adhere to a more virtuous way of life that was in line with Buddha’s Four Noble Truths.

Besides pursuing spiritual awakening individually, Asoka incorporated many Buddhist principles into the empire’s social and political practices. For example, he created a position of Dhamma-Mahamatras who had the duties of teaching the “right conduct” to the population of the Mauryan Empire in accordance with the Buddhist teaching and also supervising their behaviors (Kulke and Rothermund 2004, 66). As mentioned by Voss (2016), “to protect with Dhamma [or, in other words, the right conduct], to make happiness through Dhamma and to guard with Dhamma,” became the king’s mission statement as a political leader (8). This statement implies that it was highly important for Asoka to ensure that the Buddhist way of living was accepted and understood across the different regions of his own state and also abroad.

With this purpose, the Mauryan king encouraged missionary work and sent ambassadors to various distant countries. Some of them included such western states as Greece and Macedonia (Kulke and Rothermund 2004). Moreover, Asoka’s “missionary zeal” largely contributed to the transmission of Buddhism to Southeast Asia and northwest India from where it reached central Asia and, centuries after, China through the Silk Road (Kulke and Rothermund 2004, 66). It seems that the king’s passionate devotion to the Buddhist teaching, his leadership mission, and active efforts to promote the principles of the right conduct became a major prerequisite for the widespread dissemination of Buddhism.

Overall, Asoka’s politics fostered the incorporation of Buddhist principles in Indian culture, as well as the individual and social lives of local people. At the same time, the existing system of trade routes substantially facilitated the development of intercultural ties between India and the neighboring states. It may be argued that without this system, the efficacy of Asoka’s missionary efforts could be lower. Therefore, the following section of the paper will focus on the description of the Silk Road’s characteristics, its functions, and roles in the Mauryan Empire, and Asoka’s efforts to spread Buddhism.

The Silk Road

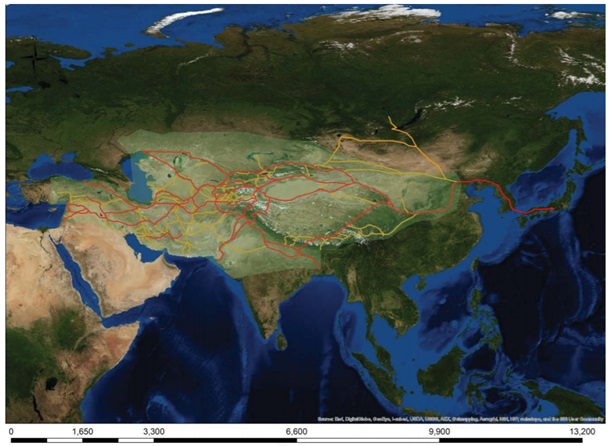

Many people today consider that the term “Silk Road” refers to a single and well-defined trade route. Nevertheless, the concept is used when speaking of a very complex communication network that linked several long-distance destinations (Williams 2014). Figure 2 demonstrates that the numerous Silk Roads connected the societies of different regions in Asia and the Mediterranean. Besides, it indicates that a large number of significant trade routes extended through the northern parts of the Mauryan Empire. Through these routes, the Mauryan dynasty established economic connections with many other dynasties, such as the Han Empire in China, the Kushan Empire in Afghanistan, and the Sassanid Empire in Persia (Williams 2014). However, one of the main functions of the Silk Road was the spread of ideas, knowledge, languages, religions, and other intangible yet highly valuable resources. According to Williams (2014), by supporting intercultural and social exchange, the Silk Road contributed to the formation and evolution of many societies and their identities. This statement is verified by the fact that Buddhism that originated in India became an essential element of culture in many dynasties and states across which those trade routes extended.

Three of the main ways through which cultures, religions, and ideas traveled on the Silk Road from one society to another are languages, artwork, and various manuscripts. Gupta, Gupta, and Gupta (2017) indicate that a significant number of ancient original literary and religious documents written in such languages as Sanskrit and Prakrit were found by archeologists on the territory of Central Asia. Scholars suggest that those documents were originally created in India and later transferred to Asian towns by people traveling across the trade routes (Gupta et al., 2017). There is also a high chance that some of those or similar manuscripts were delivered to the settlements in Central Asia (modern Afghanistan and western Iran) by Asoka’s missionaries (Gupta et al., 2017). As Gupta et al. (2017) note, the chair of the king’s Buddhist council established in 247 BC, a monk Tissa, as well as other monks, Asoka’s own brother and son, participated in that missionary work. It can signify that the spread of Buddhism in Central Asia and beyond was largely due to their efforts and Asoka’s orders.

It is worth noting that missionaries normally did not travel to other empires and regions all by themselves. In order to reduce travel costs and minimize risks, they joined trade caravans and, as mentioned by Voss (2016), frequently, “the missionaries were merchants themselves” (9). In other words, side by side with monks, many lay followers of Buddhism, the so-called “traveling businessmen,” also participated in the spread of this religion (Voss 2016, 9). It can be argued that many merchants commenced practicing and propagating Buddhism thanks to Asoka’s awareness-raising endeavors and active promotion of spiritual values among citizens. At the same time, since merchants normally used the Silk Road for reaching distinct settlements and points of sale, it is apparent that Buddhism traveled through those trade routes along with businessmen’s goods and caravans.

Besides the missionary work, another important aspect of the king’s mission to spread Buddhism was the establishment of numerous stupas, pillars, and stone edicts across the empire. According to Abakerli et al. (n.d.), the Mauryan Emperor erected as many as 84,000 monuments, and many of them “were inscribed with royal encouragements to his subjects to live in harmony with one another” (3). According to Voss (2016), Asoka located those pillars and stupas in the most significant places of Gautama Buddha’s life, which were “webbed together with a modern road system” (9). As for rock edicts that were placed outside the territory of modern-day India, a lot of them contained bilingual inscriptions. For example, in Afghanistan, researchers discovered monuments with the king’s messages in Greek, Khorosthi, and Aramic (Gupta et al., 2017). These findings and remains of edicts and pillars established by Asoka indicate that he was very strategic in the realization of his plan. Moreover, he likely was well-aware of the importance of the road infrastructure in the dissemination of knowledge in both his domain and beyond. As a result, when moving on the Silk Road, travelers from diverse backgrounds had a lot of opportunities to encounter religious Buddhist sights. They could easily get familiar with the meanings of messages on different monuments as well since the Buddhist principles were carved on them in travelers’ mother tongues.

Promotion of Buddhism as a Political Strategy

Asoka’s enormous efforts aimed to propagate Buddhism signify that spirituality indeed meant a lot to him. Nevertheless, it is appropriate to note that he promoted this religion not only as a result of compliance with personal beliefs but with political purposes as well. After all, he never renounced his responsibility as a leader of an empire and, thus, regarded it as a priority. Hutchinson (2009) states that Asoka strived to increase the awareness of the principles of Dhamma as a method of unification. He became able to control the social environment more efficiently “through a common set of values and beliefs present among many of the people of India at the time” (Hutchinson 2009, par. 2). Besides, he seemed to realize that violence associated with aggressive expansion policies could induce despise and distrust of citizens towards him and, thus, lead to political instability. On the contrary, the encouragement of tolerance and goodwill among people could help him to win the hearts of the latter (Hutchinson 2009). However, it would be wrong to presume that the Mauryan king was manipulative in his intentions. It is more likely that both the political and the spiritual domains of life were equally important for him.

Overall, it is valid to say that Asoka had a realistic attitude toward the promotion of Buddhism. For instance, one of the king’s inscriptions cited by Hutchinson (2009) in his article was as follows: “… my sons and great-grandsons should not think of a fresh conquest by arms as worth achieving, that they should adopt the policy of forbearance and light punishment towards the vanquished even if they conquer a people by arms, and that they should regard the conquest through Dharma as the true conquest” (par. 5). By saying this, the king acknowledged that violence in politics is almost unavoidable and that the Mauryan Empire might continue to expand further in the future. However, he encouraged his predecessors to stay away from tyranny and adhere to more peaceful means and behaviors as they could help the latter to sustain the large empire and rule it more effectively. When showing compliance with his own beliefs, Asoka turned into one of the first and most historically significant transformational leaders. He changed the cultural environment not merely in his own domain but many others also.

Conclusion

As the literature review revealed, Asoka played a major role in the spread of Buddhism in both India and a plethora of Asian states. The policies enacted by the king, as well as practices performed during his reign to promote awareness of Dhamma, allowed a greater number of people to learn about the Buddhist way of life. Throughout Asoka’s rule, a lot of culturally significant Buddhist artifacts appeared. Nomads, merchants, and missionaries could easily encounter them while traveling through the Silk Road or when purposefully transporting them to distant territories. In this way, they either developed their own knowledge of Buddhist principles or disseminated valuable ideas and information among other individuals and societies.

At the same time, it is clear that the well-developed network of trade routes that connected the Mauryan Empire with far-away dynasties largely facilitated Asoka’s missionary work. Since the exchange of cultures is one of the primary functions of the Silk Road, Buddhism that commenced thriving during Asoka’s reign traveled through them almost naturally. Based on that, it is true to conclude that both the Silk Road system and Asoka’s mission made the integration of Buddhism into a vast number of Asian countries possible. However, the politics of the Mauryan king still played the main role in this process because it is much harder to disseminate cultures and ideas which are available to merely a limited number of people and which are poorly rooted in the social environment.

Bibliography

Abakerli, Stefania, Amy Chamberlain, Shantum Seth, Sanjay Saxena, Navajeet Khatri, and Christiaan Kuypers. n.d. The Buddhist Circuit in South Asia. Web.

Rich, Tapas Kumar. 2013. “Buddha Philosophy and Western Psychology.” Indian Journal of Psychiatry 55 (Suppl 2): S165-S170.

Chakravarti, Ranabir. 2015. “Mauryan Empire.” In The Encyclopedia of Empire, edited by John M. MacKenzie, Nigel R. Dalziel, Nicholas Doumanis, and Michael W. Charney, 1-7. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Gupta, Archana, Aradhana Gupta, and Akanksha Gupta. 2017. Silk Road and Buddhism in Central Asia. Web.

Hutchinson, Patrick M. 2009. “Impressions of Ashoka in Ancient India.” Inquiries 1 (11): 1.

Kulke, Hermann, and Dietmar Rothermund. 2004. A History of India. 4th ed. New York: Routledge.

“Maurya Empire of India.” n.d. World Coin Catalog. Web.

“The History of Buddhism.” n.d. Khan Academy. Web.

Voss, Thomas. 2016. “King Asoka as a Role Model of Buddhist Leadership.” Thesis for Master of Arts in Buddhist Studies, University of Kelaniya.

Williams, Tim. 2014. The Silk Roads: An ICOMOS Thematic Study. Web.