Introduction and General Approach

The concept of leadership has attracted the attention of many scholars over the years. According to Redford (2020), an organization’s ability to achieve sustainable success depends on the governance approach and policies developed and implemented by those in positions of power. Collie (2021) argues that traditionally, the authoritarian approach to governance was considered the most effective.

In such an environment, a leader issues instructions, and subordinates are expected to follow them without question. Any disobedience within the system would be punished, and the opinion of followers would not be considered valuable (Adnan et al., 2020). However, the trend has changed, and companies are embracing new concepts of leadership. The Maritime and Coastguard Agency (2020) reports that in modern society, different leadership styles are required in various settings. One needs to understand when and how to apply specific governance approaches.

The quality of a leader and the approach that they take to govern may depend on various factors. In the military, the concept of absolute power, as defined in authoritarian leadership, is still the most preferred method of governance. Adnan et al. (2020) explain that in such a setting, decisions must be made as quickly as possible, and all officers should have a central command to avoid confusion. The commander’s instructions must be strictly followed to ensure proper coordination.

On the other hand, a manager of a local retail store in a highly competitive market cannot embrace such an approach to governance, as Buford (2022) observes. First, there are laws in place to protect employees, which prohibit managers from making arbitrary decisions without consulting subordinates who will be affected (Wolor et al., 2020). Secondly, there is the risk that talented employees may leave a firm where they believe another company is not considering their interests.

At sea, the concept of leadership is crucial due to the numerous challenges sailors face. Chauhan, Ali, and Munawar (2019) argue that seafarers are often governed like military personnel. Any miscommunication or misinterpretation of information can lead to costly mistakes at sea or in port.

Just like military personnel, seafarers are often faced with situations that require decisions to be made within a short timeframe. There is no time to debate the right action to be taken. The leader, often one of the most experienced and knowledgeable individuals in the crew, is trusted to make decisions when urgent action is needed (Thomson, 2021; Redford, 2020).

There are instances where the leader may consult with immediate subordinates to gain a better understanding of a situation. However, it is critical to ensure that the one at the helm of the leadership is granted the opportunity to make important decisions (Chauhan, Ali, and Munawar, 2019). In this paper, the researcher aims to investigate leadership at sea, comparing the quality of naval versus merchant seafarers’ leadership.

Aim and Objectives

Scholars have conducted wide studies on the concept of leadership. It is essential to define the specific issue concerning leadership that the study seeks to investigate. The primary aim is to contrast the quality of leadership between naval and merchant seafarers. The analysis will investigate leadership approaches at sea and how the two types of seafarers experience leadership based on the nature of their job and the environment in which they conduct their activities. The following are the specific objectives that the researcher seeks to achieve through this study:

- To investigate the quality and nature of leadership at sea;

- To compare the leadership experience of naval seafarers with that of merchant seafarers;

- To determine when a leader needs to transition from one leadership style to another to achieve success at sea.

Background

The concept of leadership has attracted the attention of scholars over the years. It is necessary to review what other studies have found concerning leadership at sea. Choi et al. (2019) explain that seafarers face unique challenges while at sea, which require effective leadership. Sometimes, the difference between life and death is defined by the approach to leadership that those in positions of power adopt (Frick et al., 2021).

At this initial stage of the review of the literature, it is necessary to explain the difference between merchant and naval seafarers. The merchant is the seafarer who travels with the boat as it conducts its travels. On the other hand, the naval is responsible for most of the smooth operations and significant occurrences above the deck (Sluis, 2021). The following research examines the concept of leadership in marine and related fields.

There is a distinction between the two seafarers in terms of their roles and places where they are specifically expected to work. Therefore, it means that the type of management required by the two seafarers may be different (Hunneman et al., 2022). Although they both work in a highly demanding and sensitive environment, the nature of their work means that others require a stricter and more organized form of leadership than others, as Pak and Desimone (2019) suggest. Several other studies have also supported the argument that merchant and naval seafarers require varying styles of leadership because of the different environments in which they work (Cuhadar, 2022). The following are the specific objectives that the researcher needed to achieve in this section of the literature review.

- The researcher must identify the most suitable sources for their specific information needs.

- The analysis must efficiently identify information sources.

- Analyze information sources critically in light of particular information demands.

- Additionally, the study will analyze and elaborate on the social and ethical ramifications of the production and use of information.

Literature Review

There is a wide range of tasks that different types of seafarers are expected to do on board a ship. According to Dedekorkut-Howes, Torabi, and Howes (2021), seafarers are, among other things, those whom a ship owner has hired to provide service on board a ship at sea or work done by people who take part in the operation and maintenance of the boat and the boarding of passengers. It means that the tasks of these seafarers range from conducting regular inspections of the vessel before it departs, assisting passengers to board, serving them, and loading and unloading baggage and other cargo. They are also involved in directly assisting the captain in operating the ship while at sea, managing emergencies that may arise, and any other task that may be assigned to them (Brooks et al., 2019). Depending on the area in which one is assigned, the nature of governance needed will vary.

Individuals working on ship repairs and maintenance, as well as special ship workers hired to work at sea on board a vessel, and cleaning and catering staff, can all be considered seafarers. Surabaya, Yulianti, and Erlando (2022) explain that when they don’t carry out the tasks above, certain groups of people working on boats who also have tasks on land are not regarded as seafarers.

For instance, offshore professionals, journalists, researchers, cooperating shipping businesses, cooperating craftspeople, and service technicians are not considered seafarers. This is because they are not directly involved in the ship’s normal operations (Aldighrir, 2020). The people are entitled to minimal protection, which includes the right to rest and care and, in some circumstances, the right to quit and get compensation for lost property. Sometimes, basic training and health certificates are prerequisites.

Empirical Review

The working conditions for seafarers are unpredictable due to limited interaction opportunities, and the crew is often cut off from society. They spend extra time apart from their loved ones. Therefore, leadership at sea is essential since it significantly impacts the efficiency, security, and working conditions on board (Nilsson and Saetre, 2021). The research identified how future marine engineers and seasoned experts view maritime leadership.

The findings, as demonstrated through subjective quasi-interviews with participants from both groups, showed that seasoned professionals and aspiring marine engineers share the same opinions on what constitutes good leadership at sea. Epstein and Boone (2022) note that both parties agree that a good leader should resemble a transformative leader in many ways. The findings of this study highlight the significance of effective leadership at sea, not only in terms of issues relating to workplace safety and conditions but also in terms of long-term interests in maritime technology learning.

While on the high seas, the ship may encounter various challenges that would require quick thinking and effective decision-making among leaders. Kuehn (2022) explains that one of the possible challenges is piracy. Effective leadership begins by understanding the areas most severely affected by the problem of piracy. The Straits of Malacca, Singapore, and the Gulf of Guinea are some of the worst-affected areas by the problem of piracy (Cusumano and Ruzza, 2020). The East African Coast, especially near the border with Somalia, is also considered a common ground for the Somali pirates. An effective leader is expected to understand these threats and develop a plan on how to counter them.

Robinson (2019) observes that it may not be possible to predict when and where the ship may be attacked. However, the team must be ready in case of an attack. The crew will expect those in positions of power to demonstrate leadership and effectively guide the team in overcoming the challenge.

In some cases, it may be necessary to negotiate with the attackers to overcome the challenge. In such a case, the leader must be a good communicator and be able to convince their attackers to release the ship (Sluis, 2021). In other cases, the crew may need to employ defensive strategies as they call for help to prevent the pirates from taking control of the ship.

The research is identified with the topic under investigation despite the differences in the geographical setting (Sebastian and Chen, 2021; Redford, 2020). Both researchers agree that leadership is vital in delivering good ship transport services. Another challenge between the two pieces of research is that. The report states that leaders are constrained in their policy options due to the desire to preserve their political legitimacy, as they attempt to cooperate with and please those they perceive as crucial to sustaining their winning coalition (Sebastian and Chen, 2021). Additionally, group leadership played a crucial role in determining the level of employee activity.

Creating methods for psychological safety and wellness that align with current practices and standards in physical health may take time, given the diversity of the existing literature (Bell et al., 2020). No consistent frameworks exist to bring together the existing work in the field or establish a proper standard for evaluating it. Additionally, sufficient data from many intervention strategies have been gathered to pinpoint the essential elements that improve mariners’ psychological well-being (Brown, 2019).

Meanwhile, those mariners have distinct preferences regarding therapies, usually ones with a physical focus or more intense leisure activities, which shows that a clear focus on employee voice is necessary to manage different expectations among stakeholders. Finally, the available evidence base’s diversity may be a strength rather than a weakness. It may be possible to develop techniques and interventions by enhancing communality and long-term interests through the generation of new methods for analyzing current information.

Limited research directly links leadership at sea with seafarers; hence, the study relied mainly on observations and surveys conducted during actual trips. The literature content available differed from the expectation in that it addressed a single section of the research. For instance, politics significantly impacts leadership formats and strategies at sea (Sulaiman, 2019). It directly addressed leadership at sea and focused on how leadership decisions impact the working environment and long-term interest in maritime technology.

However, the researchers needed to identify how each category of seafarers, such as the naval and merchant, is affected by leadership and management at sea. These were the main challenges the research faced, limiting its effectiveness in conducting an accurate study and necessitating further examination by those interested in understanding the scope of leadership at sea.

Theoretical Review

Leadership is defined using specific theories such as trait, transactional, transformational, and contingency theories, among others. As Palmer (2022) explains, there is no specific leadership style that can be considered universally acceptable. Different situations would require different leadership strategies. A leader must understand when it is appropriate to apply a specific leadership theory (Demirtas and Karaca, 2020). These theories are critical to the study, as they represent common leadership aspects applicable to most organizations.

Thomas Carlyle coined the trait theory in the 1800s, which dictates that leaders are born with specific characteristics that influence their performance and behavior. According to the trait theory of leadership, leaders are defined by a set of innate or inborn traits (Demirtas and Karaca, 2020). These characteristics could be psychological, physiological, intellectual, or other traits.

Essentially, the leader and their attributes are what make an organization successful, according to trait theory. It is assumed that identifying individuals with the right qualities would enhance organizational performance (Palmer, 2022). The follower is entirely ignored by trait theory, which only considers the leader.

Authoritarianism is another leadership style that seafarers can employ. According to Demirtas and Karaca (2020), this occurs when the leader is expected to issue instructions that must be followed by subordinates without question. This dictatorial approach to leadership may appear undesirable, but there are cases when it is the most appropriate governance strategy. When a major challenge arises at sea, such as a severe storm or a pirate attack, the captain must provide the necessary leadership (Epstein and Boone, 2022).

In such emergencies, there is no time for the entire crew to assess the situation and consult widely. Everyone on board the ship will rely on the knowledge, experience, and skills of the leader (Palmer, 2022; Cusumano and Ruzza, 2020). The leader will be expected to issue directions, and the crew will follow them without question. Although it may not be used at all times, there are instances when it has to be applied to overcome obstacles.

Coaching is another possible leadership style that can be considered among naval and merchant seafarers. According to Robinson and Gray (2019), seafarers are required to handle unique tasks that can impact the lives of those on board and the safety of the cargo. It means that a simple mistake, if not identified and corrected on time, may have devastating consequences. When a firm recruits seafarers, they must undergo a rigorous training process before being allowed to handle specific tasks, especially those associated with high risks at sea (Demirtas and Karaca, 2020).

In this stage, these individuals require coaching on the right leadership style. The leader is expected to work closely with the recruits, understanding that their inexperience may cause specific challenges in their activities. Instead of reprimanding them when they make mistakes, the leader is expected to offer them guidance.

Sebastian and Chen (2021) argue that this initial stage of employment is where a seafarer is expected to make mistakes because they will learn from them, and they are under constant supervision. Coaching is suitable for inexperienced seafarers because it fosters a learning environment. Whenever a new practice or concept is introduced in the firm, coaching should be extended to even the most experienced employees, as they, too, will need to learn.

Max Weber created the transactional theory of transactional leadership. The theory suggests that some leaders are more interested in motivating their subordinates to efficiently attain organizational goals (Alrowwad, Abualoush, and Masa’deh, 2020). An individual who appreciates structure and order is a transactional leader. This form of administration oversees military operations to accomplish goals on schedule, transports personnel and supplies in an orderly manner, and manages significant enterprises or international initiatives.

Transactional leaders need to work more effectively in environments that foster innovation and creativity. Self-motivated individuals who perform well in a structured, guided environment are necessary for transactional leadership (Shou, 2021). In contrast, transformational leadership aims to inspire and motivate employees. It favors the influence over direction. This theory applies in the sea industry to encourage seafarers to interact and function as a team to meet objectives.

A leadership style known as transformational leadership affects both social systems and individual behavior. In its optimal state, it brings about significant and constructive change in followers, with the ultimate objective of transforming them into leaders. James MacGregor Burns developed the theory in 1978 to illustrate how leadership can socially elevate society (Robinson and Gray, 2019). Transformational leadership enhances followers’ motivation, morale, and productivity through several processes when practiced in its purest form. Connecting the followers’ sense of identity and self to the organization’s mission and collective identity is another key aspect.

These theories are essential in the report since they portray different forms of leadership in society and their primary objectives. The approaches aid in selecting the research topic, choosing pertinent data, interpreting the facts, and suggesting explanations of the factors that may have contributed to the observed events. By pointing to places that are most likely to be fruitful, i.e., locations where substantial correlations among variables are expected to be identified, theory provides significant directions and paths for research (Shou, 2021).

No matter how precise the subsequent observations and deductions are, the investigation will only be fruitful if the variables are chosen so that no links exist. A theoretical theory constrains the universe of facts that can be explored. Theoretical frameworks provide researchers with a clear point of view and a path to follow when investigating the connections between specific variables from an almost endless range of variables.

Hypotheses

The review of the literature presented in the section above helps in understanding the type of leadership required at sea. It is evident that in many cases, authoritarianism may not be avoidable, especially when major challenges threaten normal operations at sea, the lives of the crew, or the safety of goods in transit. Above the deck, there are instances where strict rules must be observed to ensure the safety of both goods and people during loading and unloading operations (Adnan et al., 2020). Despite the numerous similarities in the type and quality of leadership experienced by naval and merchant seafarers, some differences were also observed. Based on the findings from the literature, the following hypotheses were developed. The researcher seeks to confirm or reject the hypotheses based on data collected from primary sources.

- H0: Naval and merchant seafarers experience the same quality of leadership.

- H1: Naval and merchant seafarers do not share the same quality of leadership.

Methodology

In this chapter, the focus is on explaining how primary data were collected and processed to help achieve the study’s objectives and to confirm or reject the formulated hypotheses. Asari and Rashed-Ali (2021) explain that, after reviewing the literature and understanding the existing knowledge gaps, the collection and analysis of primary data make it possible to accurately address research questions.

This chapter explains the research philosophy, research approach, design used, and data collection method, which includes the sampling method, sample size, questionnaire design, and steps taken to collect and process primary data. It also discusses the data analysis method, validity and reliability issues, limitations, and ethical considerations.

Research Philosophy

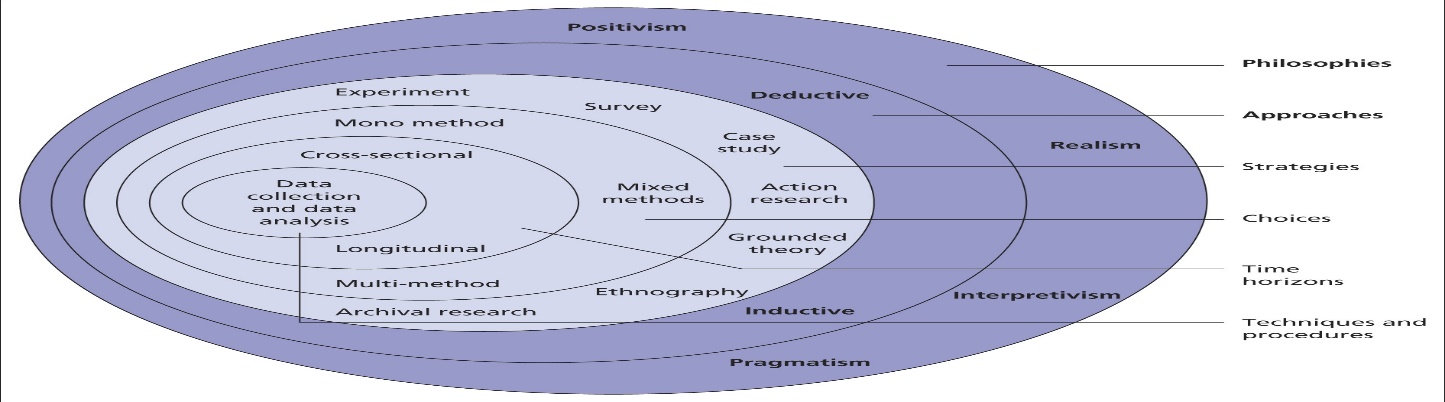

When planning to conduct research, one of the key factors that must be clearly defined is the philosophy that underlies all the assumptions that will be made. When selecting the philosophy, the focus should be on the aim and objectives of the study. One can employ positivism, realism, interpretivism, or pragmatism, depending on the goal that needs to be realized.

Interpretivism holds the belief that one can only access reality through social construction. It is a philosophy that is popular when conducting qualitative research (Eden, Nielsen, and Verbeke, 2019). As such, it was not appropriate in this project, as a statistical analysis was needed to confirm or reject the research hypotheses developed after the preliminary review of the literature.

Pragmatism is one of the most widely used research philosophies in the social sciences. The proponents of this philosophy hold the view that there are many ways of interpreting the world and that no single viewpoint can provide a comprehensive understanding of a concept (Grønmo, 2020). As such, it encouraged mixed-method research to facilitate a comprehensive analysis of the issue under investigation.

The researcher was not interested in conducting a qualitative analysis alongside the statistical review. As such, the philosophy was considered inappropriate. On the other hand, realism is the view that reality is independent of human minds and that true knowledge can only be developed through scientific methods (Hennink, Hutter, and Bailey, 2020). The philosophy is often employed when conducting a pure research project. As such, it was also considered inappropriate for this study.

Pragmatism was chosen as the appropriate philosophy, whose assumptions and principles align with the goals and objectives of this study. The philosophy of factual knowledge can only be gained through observations and measurements (Hennink, Hutter, and Bailey, 2020). As such, the role of a researcher should always be limited to collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data.

The researcher is not expected to influence the subject being investigated in any way, and when possible, the population under study should be captured while behaving normally. In this case, it was necessary to assess leadership at sea by closely comparing the leadership qualities and experiences of naval and merchant seafarers. Figure 1 outlines the different philosophies and other factors that must be considered when collecting and processing primary data.

Research Approach

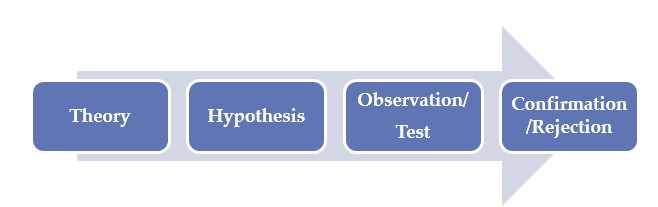

When the research philosophy has been selected, the next step is to identify the appropriate research approach. In this context, the research approach refers to the general procedure of conducting research. One can primarily use a deductive or inductive approach to conducting research. Symbaluk (2019) advises that the chosen research approach should align with the selected philosophy. The inductive approach begins by making observations or conducting tests, and then observing patterns before a theory can be developed (Asari and Rashed-Ali, 2021). In this study, the focus was not on developing a new theory. As such, this was not the most desirable research approach for the study.

The deductive approach is another popular reasoning method that can be used to conduct a study. It requires a researcher to start by identifying a theory upon which the study will be based. The researcher is then expected to develop a relevant hypothesis that reaffirms or challenges the identified hypothesis (Eden, Nielsen, and Verbeke, 2019). Data will then be collected through observation, and a test will be conducted. The outcome of the analysis should accept or reject the hypothesis. The confirmation or rejection of the hypothesis helps determine the relevance of the specific theory within a given context. The research approach to be taken when using deductive reasoning is illustrated in the figure below.

Research Strategy

When collecting primary data, it is often advisable to choose a strategy that allows for the easy gathering of the desired information from the targeted individuals or sources. As shown in the research onion above, one can use experiments, surveys, case studies, action research, grounded theory, ethnography, or archival research to gather the needed information. In this study, the researcher considered a survey to be the most appropriate method for collecting data from the participants.

The researcher identified a sample of participants who could explain the concept of leadership at sea, particularly the leadership experiences of naval and merchant seafarers. The survey was considered appropriate because it enables the collection of data from a wide range of individuals (Schram and Aljaž, 2019). If an online survey is used, it becomes possible to collect data from a relatively large sample size within a relatively short period.

Data Collection Method

After defining the research strategy, the next step is to collect data from the targeted population. Grønmo (2020) advises that when collecting primary data, care should be taken to ensure that those involved have the necessary knowledge and experience in the issue being investigated. In this project, the focus was on leadership at sea, specifically comparing the leadership characteristics and perceptions of marine seafarers with those of trade seafarers. Identifying the right population was critical before sampling was done. Primary data was obtained from the merchant and marine seafarers.

Sampling and Sample Size

Sampling is often essential when data is to be collected from a relatively large population. According to a report, it is estimated that 21,970 UK nationals were on active duty at sea in 2021 (United Nations, 2021). It is not possible to collect data from the entire population. It becomes necessary to select a small sample from which data is to be obtained. The stratified sampling technique was considered the most suitable method for identifying participants who needed to participate in the study.

The strategy involved classifying the participants into two groups, marine seafarers and merchant seafarers (Schram and Aljaž, 2019). In the two strata, the researcher used a simple random sampling technique to identify participants. The approach was meant to ensure that both individuals working as merchant seafarers and those working as marine seafarers are adequately represented in the study. Slovin’s formula, shown below, was used to calculate the sample size.

Sample Size = N / (1 + N*e2)

N = population size

e = margin of error

N = 21970

e = 5% or 0.05 (the confidence level is 95%)

Sample size = 21970/ {1+ 21970(0.05)²}

= 21970/ {1+ 21970 x 0.0025}

= 21970/ {1+ 54.925}

= 21970/ 55.925

= 392.84

Which means the sample size should be 393 individuals. The researcher successfully recruited 260 individuals to participate in the study.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

A researcher is expected to set specific conditions that respondents must meet to qualify for participation in the study. The primary qualification for the study was that one had to have worked as a merchant or marine seafarer for at least three years. Individuals who had worked in the industry for less than three years were excluded from the study. The second inclusion criterion was that one had to be from Western European countries or North America, with UK nationals being given priority.

The rationale for defining the nationality of the respondents was informed by the fact that leadership styles in some countries differ significantly from those in other countries. For instance, China and North Korea are two countries where authoritarian forms of governance are generally tolerated (Coe et al., 2021). As such, their perception of leadership differs significantly from that of the West, where democracy is highly regarded. As such, those individuals had to be excluded from the study. The participant had to be a merchant or naval seafarer to be included in the study. Those who could not be classified into any of the two groups were excluded from the study.

Questionnaire Design

The researcher developed a questionnaire to facilitate the process of collecting primary data. As Tracy (2019) advises, the use of a questionnaire helps ensure that data is collected in a standardized manner. When collecting data that is to be processed quantitatively, the questionnaire should ensure that the data can be easily coded. The questionnaire had three sections.

The first section of the document focused on the nationality and demographics of the participants. Grønmo (2020) explains that sometimes there is always bias along gender or racial lines. It is common for employees to respond differently to a reprimand by the management based on their race. One can develop the impression that the manager is being harsh to them due to their racial differences. Others may blame it on gender, believing that the other gender is treated better.

The second section of the document focused on the academic and work experience of the participants. According to Deplano and Tsagourias (2021), the trustworthiness of a response from an individual is often based on their academic experience. For many years, scholars have shown interest in studying the concept of leadership, and a highly educated respondent is likely to provide a knowledge-based response on the issue under investigation, rather than basing their response on rumors. The participants’ experiences were also critical. Those who have worked as naval or merchant seafarers for many years have the capacity to provide trustworthy information.

The last section of the document focused specifically on issues about the leadership at sea. The questions focused on explaining the leadership qualities and experience that naval seafarers possess and comparing them closely with those of merchant seafarers. These questions focused on achieving the study’s aims and objectives. The researcher ensured that closed-ended questions, also known as structured questions, were used. It made it possible to code the responses obtained to conduct a mathematical analysis.

Data Collection

When the participants for the study had been identified, the next step was the actual data collection process. The researcher contacted the sampled participants through direct phone calls and messages through specific social media platforms. The researcher explained to them the significance of the study, the role they were expected to play, and the reasons for their selection to participate in the investigation. For those who agreed to participate in the data collection, a questionnaire was provided with instructions on how to complete it. They were informed to answer all the questions and then email back the document. They were given one week to complete the task.

Data Analysis

After collecting primary data from the participants, the next phase is to process it to respond to the research aim and specific research questions. To achieve this goal, a comparative analysis was necessary. That could only be achieved by conducting a qualitative analysis (Deplano and Tsagourias, 2021).

To process the primary data and establish the significance of the relationship between the variables, the researcher used the Kruskal-Wallis H test (one-way ANOVA). This enabled the researcher to test the hypotheses. The researcher coded responses from participants and then used an Excel spreadsheet to process data. The outcome of the analysis was presented in the form of charts to facilitate easy interpretation of the findings.

Validity and Reliability Issues

The concept of leadership remains crucial in various contexts worldwide. Leadership qualities and experience needed at sea are significantly different from those required in a production plant within a large company (Tracy, 2019). As such, findings made from this study will be crucial for stakeholders in the shipping and related industries. It was necessary to ensure that the information presented in the study was reliable and trustworthy. The validity of the study was ensured by verifying that the instrument used to collect data was capable of gathering the desired information.

Before collecting data, a pilot study was conducted, as Grønmo (2020) suggests, to ensure that the questionnaire was not too complex or confusing for participants to understand what was required of them. To enhance the reliability of the study, the researcher ensured that primary data were collected from a diverse range of sources. When engaging with participants, the researcher maintained clear and regular communication to ensure that all concerns and clarifications were addressed.

Limitations

It is essential to note that during the course of this study, the researcher encountered several challenges worth mentioning. One of the major challenges encountered was the withdrawal of some of the participants. It took time to identify individuals with the right information about the leadership at sea, especially those who understood the leadership quality and experience of marine and trade seafarers. Those who withdrew from the study had to be replaced to ensure that data saturation was achieved, a process that consumed time.

Despite the challenge, the researcher was able to sample an adequate number of individuals to facilitate data collection within the available time frame for the study. Finding relevant materials for the study, especially literature that specifically focuses on naval and merchant leadership experience and quality, proved to be challenging. Despite this challenge, the researcher successfully identified participants for the project.

Ethical Considerations

When conducting research, it is crucial to consider the ethical implications. Grønmo (2020) explains that when collecting data from primary sources, one of the key ethical considerations is the need to protect the identity of the participants. Intolerance and extremism are common social challenges in the United Kingdom and other countries around the world. It is common to find cases where one is persecuted because their beliefs on an issue differ from those of the majority or those in a position of power.

Leadership at sea is a less controversial topic in the country. However, it is essential to ensure that the identity of those who participate in the study remains unknown. Tracy (2019) explains that people tend to be more enthusiastic in a given study if they know that their identity will not be revealed. They will give their responses freely without fearing possible consequences. Instead of using their actual names, the researcher assigned the respondents unique identification codes (Participant 1, Participant 2, Participant 3, and so on).

Besides assuring them of confidentiality in the study, participants may also have some conditions before taking part in the data collection process. They may want to know the importance of the project and how it might affect them as individuals or their company (Deplano and Tsagourias, 2021). They may also want to know why they were chosen to participate in the study. The researcher ensured that all the questions and clarifications that the respondents had were fully addressed. They were also informed that their participation in this study was voluntary, meaning that anyone who felt compelled to withdraw was at liberty to do so.

When collecting data from a specific institution, it is often advisable to obtain permission from management before contacting participants. Coe et al. (2021) note that the researcher should explain the relevance of the study, justify the selection of the institution, and outline any potential consequences that may arise from the study. In this project, respondents participated on an unofficial basis. They were selected based on their industry experience, rather than their affiliation with a specific company. As such, it was not necessary to get consent from the management of the companies they were working for at the time of data collection.

In academic research, specific conditions must be met when undertaking a project. One of the key requirements is to avoid all forms of plagiarism in the report (Symbaluk, 2019). The researcher ensured that this report was written from scratch. There are various cases where the researcher had to rely on secondary data sources. Information obtained from secondary data was referenced accordingly using the Harvard referencing style. The project was completed within the time frame provided by the supervisor and submitted in accordance with the school’s regulations.

Results

In this chapter, the focus was on responding to the study’s aim and objectives, and ultimately confirming or rejecting the hypothesis developed during the preliminary literature review. Data obtained from the sampled participants were statistically processed to address a specific question. It emerged that there are specific similarities and differences between the quality and experience of marine leadership and that of merchant leadership. The chapter then addresses the hypotheses that had been developed. As shown in the calculation above, the researcher relied on the responses of 260 individuals to help accept or reject the hypothesis. The researcher used the Kruskal-Wallis H test to process the data, which is presented in this section.

Similarities

When assessing the concept of leadership at sea, the researcher considered it appropriate to start the analysis by identifying the similarities between naval and merchant leadership experiences. One of the issues that was of interest when assessing leadership experience was the ability of subordinates to make decisions in emergencies without fear of possible punishment from those in power (Wray et al., 2021). The participants were asked if naval and merchant seafarers are free in emergency decision-making.

The responses from the 260 participants were statistically analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis H test. Figure 3 shows that 33.3% of the participants strongly agreed with the statement, while another 26.7% agreed with it. It means that more than a half of participants (60%) are convinced that both merchant and naval seafarers have the freedom to make important decisions in emergency cases.

Another 26.7% of the participants reported being unsure about the freedom that seafarers have. Only 13.3% of those who participated in the study held a contrary opinion, as shown in the figure below. Based on statistical significance, one can conclude that in cases of emergency, both the naval seafarer and the merchant seafarer will have the same leadership experience in terms of their ability to make decisions without the fear of repercussions from those in power.

Supervision and familiarization are critical factors that define leadership experience. The researcher asked the participants if they felt that both naval and merchant seafarers should be supervised and aware of the organizational goals. As shown in Figure 4, 20% strongly felt that they both do, while another 60% felt that they do. An overwhelming majority of the participants, 80%, think that supervision and familiarization are needed in both cases. Another 13.3% noted that they are not sure about the issue. Only 6.7% of the participants had a contrary opinion, stating that they disagreed with the statement. Based on the statistical significance, both require some form of supervision and familiarization with the goals of their organization.

Differences

During the review of the literature, some differences in the experience of naval and merchant seafarers emerged. When collecting and processing primary data, it was necessary to capture these differences. The attention that seafarers receive from those in positions of power was one of the issues of interest. The researcher asked the respondents if they are of the opinion that leaders of naval seafarers pay more attention to staff compared to those of merchant seafarers.

As shown in Figure 5 below, 6.65% strongly agreed with the statement, while another 40% agreed with it. 26.7% noted that they were unsure about the difference. 20% of the participants disagreed with the statement, while another 6.65% strongly disagreed with the statement. A comparative analysis reveals that 46.65% agree with the statement, while 33.35% disagree with it. The fact that those who agree with the statement outnumber those who are opposed to it confirms the difference.

To gauge the perceived organizational difference in leadership, participants were surveyed on whether naval seafarers were more organized leaders than merchant seafarers. The vast majority affirmed this statement, with 26.7% strongly agreeing and 66.7% agreeing, indicating a high level of consensus.

It means that an overwhelming majority of the participants, 93.4%, agree that naval seafarers are more organized in leadership compared to merchant seafarers. 6.6% of the participants noted that they are not sure about the level of organization in leadership in both contexts. None of those who took part in the analysis had a contrary opinion. It means that there is an overwhelming belief that marine seafarers tend to experience a more organized leadership than merchant seafarers.

Another factor that defines leadership experience is the level of autonomy or freedom one has within an organization. The researcher asked the participants to state whether naval seafarers experience more freedom to make decisions compared with merchant seafarers. 20% of the participants consider that naval seafarers experience greater freedom. Another 46.7% of the participants agree with the same statement.

It means that those who feel that naval seafarers have more decision-making freedom were 66.7%. The results show that 20% were unsure about the difference in experience, while another 20% disagreed with the statement. Based on the majority of views obtained from the study, the conclusion made was that naval seafarers experience greater freedom to make major decisions in their workplace than merchant seafarers.

Hypotheses

The analysis above shows that naval and merchant seafarers often face similar or different circumstances, depending on the work environment they encounter. There are cases when the leadership quality and experience are identical, while in other cases, they differ. The hypothesis developed focused on addressing the possible similarity of the experience. The researcher had to directly respond to the hypotheses that had been developed.

To test the hypothesis, participants were asked directly whether naval and merchant seafarers experience the same level of leadership in their work. As illustrated in Figure 8, 53.4% of respondents agreed with the statement (comprised of 26.7% strong agreement and 26.7% agreement), which is more than double the 26.6% who disagreed (split evenly between disagreement and strong disagreement). 20% of participants remained unsure. The data clearly indicates that those who perceive leadership levels as equal significantly outnumber those who believe they differ. It means that the null hypothesis is accepted while the alternative hypothesis is rejected.

Further analysis was needed to test the null hypothesis that leadership quality is equal among naval and merchant seafarers. When participants were asked if merchant seafarers were more experienced leaders than their naval counterparts, the responses were nearly evenly split. Specifically, 46.7% disagreed with the statement, while 46.6% agreed. The remaining 6.7% were undecided about the comparison.

Statistically, those who agree with the statement are just as many as those who disagree with the statement. Those who reject the claim that merchant seafarers are more experienced in leadership than naval seafarers are the slight majority.

Following the findings that naval and merchant seafarers experience similar leadership qualities, the study investigated whether different qualifications are needed for success in their respective leadership roles. When asked if the leadership demands of the two groups require distinct qualifications, a large majority of respondents affirmed this: 20% strongly agreed and 60% agreed. 13.3% of the participants were neutral, while only 6.7% held a contrary opinion. The statistics show that although the experience may be the same, the leadership qualifications needed for merchant seafarers are different from those of a naval seafarer.

Analysis and Discussion

The presentation of results based on the analysis of primary data helps to determine the views of the participants on the issue under investigation. It has made it possible to directly address the study’s aims and objectives. The section also enabled the addressing of research gaps and the direct confirmation or rejection of hypotheses developed based on the preliminary review of the literature. In this section, the focus is on integrating findings made from both primary and secondary data in a detailed analysis and discussion.

Leadership at Sea

Findings from primary sources indicate that leadership at sea is significantly distinct. According to Wray et al. (2021), in a factory setting, it is possible to ignore or even disobey a supervisor’s directive, and in most cases, the consequence would be a delay or defects in the products at the plant. A firm can easily recover from such mistakes by making employees work overtime and correcting the mistakes made. However, the same is significantly different when it comes to leadership at sea (Sluis, 2021). A directive from a captain would define how safe the crew and cargo will be on the high seas, especially during storms, heavy rains, or other turbulence. When the instruction of the leader is ignored, the mistake can lead to the destruction of property and the death of everyone on board.

Those at sea cannot afford simple mistakes, such as miscommunication or misinterpretation of instructions. Amor, Vazques, and Faina (2020) argue that seafarers must learn to operate like military personnel. Subordinates can make decisions, especially when the situation is calm and standard procedures are followed (Gemeda and Lee, 2020). Primary data indicate that both naval personnel and seafarers can make decisions in emergencies.

However, everything needs to be done in a highly coordinated manner (Pancasila, Haryono, and Sulistyo, 2020). The message must be clear when communicated, and the hierarchy of command must be respected at all times. It means that when one is instructed to undertake a given activity, they should do so without questioning the rationale unless they are strongly convinced that the instruction given is wrong and can lead to devastating consequences, or when an alternative course of action is available.

Naval and Merchant Seafarers Experience

During the analysis, the focus was to identify similarities and differences in leadership experience between naval and merchant seafarers. When analyzing the similarities, one issue that emerged was that naval and merchant seafarers can make decisions in emergency cases. Cordon (2019) explains that in an emergency, a quick decision can enable an individual to protect the entire crew and cargo. When an emergency emerges and a seafarer feels that they have the knowledge and experience to act in a way that would avert danger, they can do so immediately, especially when seeking approval may take too long to manage the problem (Cutler, 2019). Participants felt that both naval and merchant seafarers were at liberty to make such urgent actions without the fear of being reprimanded.

The primary data analysis also noted that naval and merchant seafarers need supervision and communication of organizational goals. In both cases, there is a need for the leader to supervise subordinates when a new rule is introduced or when a specific new goal needs to be achieved (Amor, Vazquez, and Faina, 2020). Familiarization enables seafarers to understand the new concept and how they can operate under the new rules and regulations (Wolor et al., 2020).

Even in cases where a leader has a team of highly skilled and disciplined seafarers, the initial stages will require some form of supervision to enable the subordinates to understand the new system. Gemeda and Lee (2020) note that a simple mistake at sea can have devastating consequences. To avoid such mistakes, the leader should ensure that the team is supervised and guided accordingly.

The analysis also identified distinctions in the leadership perception of naval and merchant seafarers. The analysis of primary data showed that naval seafarers experience more attention from leaders than merchant seafarers. The difference is primarily caused by the nature of tasks that each group is expected to perform at sea. The naval seafarers are responsible for the critical function of the ship and cannot afford to make mistakes (Pancasila, Haryono, and Sulistyo, 2020).

Attention is given to them to ensure that they closely follow the instructions provided. The leader also needs to give them close attention to ensure that, in case a mistake is made, a quick remedy will be made before serious consequences are felt (Buford, 2022). On the other hand, merchant seafarers do not require such close attention as long as every operational activity is going as planned.

The analysis of primary data also revealed that naval seafarers have more organized leadership than merchant seafarers. Cutler (2019) explains that seafarers tend to coordinate their activities closely because of the sensitivity of their tasks. For instance, an instruction from the captain should be communicated to the engineer or any other designated officer in real-time. They operate like military personnel (Cutler, 2019). The chain of command is strictly followed, as instructions come from the top to the lowest officer.

Whenever a junior naval seafarer needs to pass a piece of information to top management, it must be channeled to the immediate supervisor, who will assess it and determine if it needs to be passed on to the next level of management (Collie, 2021). On the other hand, merchant seafarers do not have to operate in such a strict leadership environment.

After reviewing the similarities and differences in experience, it was necessary to confirm or reject the hypotheses that were developed. The analysis of primary data confirmed the null hypothesis, which states that the quality of leadership is the same for naval and merchant seafarers. Data obtained from the respondents rejected the alternative hypothesis. The primary data indicate that although there may be significant differences in the skills required for naval and merchant leadership, the experience is relatively similar.

Robinson (2019) and Collie (2021) state that when at sea, the experience that the crew has is almost the same. Whenever an emergency arises, everyone’s life will be at risk. As such, the need to manage the danger will require all those at sea to act in different ways to arrest the situation (Lee, Idris, and Tuckey, 2019). Both the merchant and naval seafarers will have almost the same level of stress until the threat is effectively managed.

The Implication of the Results

The results obtained from this study have effectively achieved the study’s aims and objectives. The study has effectively investigated the quality and nature of leadership at sea. Leadership at sea is significantly different from that exercised within a production plant (Lyubykh et al., 2022). At sea, some of the instructions issued may define the difference between life and death for those on board the ship and its cargo. As such, the margin of error for these people is significantly small.

As such, instructions must be communicated in clear and concise terms, and subordinates must follow them strictly. At sea, the form of leadership practice is almost similar to that used in the military (Cheong et al., 2019). The leader has absolute authority, and unless it becomes obvious that their judgment is impaired and their decisions may endanger the crew and cargo, they must be obeyed at all times. This approach differs significantly from the one practiced in many companies, where leaders typically consult with subordinates when planning to implement a major policy change.

The study also aimed to compare the leadership experiences of naval seafarers with those of merchant seafarers. The review of the literature has revealed a difference in leadership approaches between naval seafarers and merchant seafarers (Sluis, 2021; Grint, 2021). When the primary data was analyzed, it confirmed that the leadership approach used when handling naval seafarers differs from that used for merchant seafarers. First, it became apparent that the type of training required for leaders in naval seafarers differs from that needed for merchant seafarers.

The primary data analysis also showed that naval seafarers’ approach to leadership is more demanding than that of merchant seafarers. When it came to directly responding to the research hypothesis, which focused on determining if the quality of leadership depends on whether seafarers are naval or merchant, the null hypothesis was confirmed. It was an indication that, despite the minor differences that may exist, the leadership experience of naval seafarers is relatively similar to that of merchant seafarers.

The ultimate objective was to identify when success at sea demands a leadership style transition. Thomson (2021) explains that in any organization, there is no single standard type of leadership that can be used at all times. Sometimes a leader needs to be authoritarian, while in other cases, they may need to act as a coach or even allow the subordinates to make critical decisions (Lee, Idris, and Tuckey, 2019).

The same principle applies to leadership at sea. While at sea, a leader must adapt their leadership style to suit the specific situation at hand. When faced with a major danger at sea, there is a need for strict coordination of activities, and to achieve success, authoritarian leadership may be necessary. On the other hand, a more relaxed leadership style, such as coaching, transformational, or even laissez-faire approaches, may be employed when everything is calm and there is no emergency at sea.

The need to a leadership style shift would also be defined by the experience of the seafarers. According to Grint (2021), newly recruited seafarers tend to have limited knowledge about what is expected of them. Without close supervision, Cheong et al. (2019) note that they can easily make costly mistakes during operations. As such, they will need close monitoring from their more experienced supervisors. In such a case, coaching would be the best governance approach. This approach would involve guiding the recruits to understand how various systems work and the roles that they need to play.

On the other hand, highly experienced employees would need a different approach to governance (Cordon, 2019). For instance, they adopt a laissez-faire approach, as they are not only experienced but also disciplined enough to act in a manner required of them while at sea (Lyubykh et al., 2022). Transformational leadership would also be appropriate with such experienced seafarers when there is a need to ensure that they gain knowledge about emerging technologies.

The researcher was keen on identifying and managing limitations and reasons for failure. One of the issues that emerged was the withdrawal of participants who had already been sampled. The problem was further complicated by the fact that most of these seafarers are busy and frequently move from one port to another (Robinson, 2019). As such, replacing them was a time-consuming process. Despite this challenge, the researcher was able to identify individuals who met the inclusion criteria to take part in the study. The project was completed within the timeframe defined by the supervisor.

Conclusion

Leadership is one of the most widely researched topics because of its relevance in any organizational setting. As the study indicates, whether an institution is a non-profit or for-profit entity, it will require some form of leadership. Successful organizations worldwide owe their growth to effective leadership. In this study, the focus was on leadership at sea.

As demonstrated in the review of the literature and the analysis of primary data, leadership at sea exhibits significant differences from leadership in other settings. At sea, a simple mistake may have catastrophic consequences. The margin of error in such settings is often small. As such, those who are charged with leadership responsibilities at sea must ensure that they guide the entire team with care. It explains why seafarers are governed in almost the same manner as military personnel. They have to strictly follow the instructions of their superiors at all times.

The leadership experience of naval and merchant seafarers varies depending on the situation at hand. The study reveals that the tasks naval seafarers must handle while at sea necessitate greater supervision. There is a need to maintain close and effective communication among naval seafarers because of the sensitive nature of their roles. Naval seafarers are expected to remain vigilant in their tasks, and there are cases when they are allowed to make decisions in times of emergency. The primary data also indicated that merchant seafarers are sometimes expected to make decisions and act accordingly when handling an emergency in their workplace.

When directly responding to the study’s hypothesis, the findings confirmed the null hypothesis that leadership in merchant and naval seafarers is of the same quality. The level of sensitivity of the two professions may differ, but they share the same setting and face similar dangers, which means they also experience a comparable level of stress while at sea. The respondents noted that there might be slight differences due to the specific nature of tasks each team handles while at sea. Still, the leadership quality and experience of the two are not significantly different. The study also shows that those trusted with leadership at sea should understand when to use a specific style of leadership.

When handling newly recruited seafarers, it becomes necessary to use coaching as a way of enhancing their skills and enabling them to understand what is expected of them while at sea. On the other hand, highly experienced seafarers should be offered an environment that allows them to make informed tactical decisions. The study recommends the use of transformational leadership as a way of governing such employees. Laissez-faire is another possible leadership style that can be employed when handling highly experienced seafarers at sea. In the absence of an emergency, an authoritarian form of governance is not required. A good leader is expected to know when to switch from one leadership style to another, depending on the situation at hand.

Recommendations

The findings of this study strongly suggest that leadership at sea differs significantly from that in the organizational environment, due to the unique environment in which seafarers operate. The study has also demonstrated that leadership quality is equal for both merchant and naval seafarers. However, further studies are needed. The following are the suggestions for further work for future scholars who may want to expand their knowledge in this field:

- There is a need to investigate the nature of the relationship between seafarers and their leaders in times of emergency. In such instances, the use of authoritarian leadership may be unavoidable. However, this can be done in a way that does not affect the relationship between a leader and subordinates. As such, future scholars should investigate how a dictatorial approach to governance can be used, but in a respectful way.

- Future scholars should investigate the unique relationship between naval and merchant seafarers. Such studies should specifically focus on explaining how the two professionals can coordinate their activities while at sea.

- Future scholars should explain how culture influences the leadership approach of both naval and merchant seafarers. They can compare seafarers from China or North Korea to those of the United Kingdom or the United States.

Reference List

Adnan, N. et al. (2020) ‘Relating ethical leadership with work engagement: How workplace spirituality mediates’, Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), pp. 4-13.

Aldighrir, W. (2020) ‘Mediating effect of leadership outcomes on the relationship between the leadership style of leaders and followers’ administrative creativity’, Journal of Education in Black Sea Region, 5(2), pp. 7-18.

Alrowwad, A., Abualoush, H. and Masa’deh, R. (2020) ‘Innovation and intellectual capital as intermediary variables among transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and organisational performance’, Journal of Management Development. 39(2), pp. 196-222.

Amor, A., Vazques, J. and Faina, J. (2020) ‘Transformational leadership and work engagement: exploring the mediating role of structural empowerment’, European Management Journal, 38(1), pp. 169-178.

Asari, R. and Rashed-Ali, H. (2021) Research methods in building science and technology. New York: Springer.

Bell, J. et al. (2020) ‘Health service psychology education and training in the time of COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities,’ American Psychologist, 75(7), p.919.

Brooks, C. et al. (2019) ‘Reaching consensus for conserving the global commons: the case of the Ross Sea, Antarctica’, Conservation Letters, 13(1), pp. 1-10.

Brown, D. et al. (2022) Seafarers’ psychological well-being: a rapid evidence assessment.

Buford, J. (2022) On mission: your journey to authentic leadership. Austin: Greenleaf Book Group Press.

Chauhan, R., Ali, H. and Munawar, A. (2019) ‘Building performance service through transformational leadership analysis, work stress and work motivation’, Dinasti International Journal of Education Management and Social Science, 1(1), 87-107.

Cheong, M. et al. (2019) ‘A review of the effectiveness of empowering leadership’, The Leadership Quarterly, 30(1), pp. 34-58.

Choi, J. et al. (2019) ‘An analysis of mediating effects of school leadership on MTSS implementation’, The Journal of Special Education, 53(1), pp. 15–27

Coe, R. et al. (2021) Research methods and methodologies in education. 3rd edn. London: SAGE Publications.

Collie, R. (2021) ‘COVID-19 and teachers’ somatic burden, stress, and emotional exhaustion: examining the role of principal leadership and workplace buoyancy’, American Educational Research Association, 7(1), pp. 1-15.

Cordon, J. (2019) Seaman’s guide to human factors leadership and personnel management. London: Taylor and Francis Group.

Cuhadar, S. (2022) ‘Challenges and opportunities of e-leadership in organisation s during covid-19 crisis’, Practical Application of Science, 10(29), pp. 83-88.

Cusumano, E. and Ruzza S. (2020). Piracy and the privatisation of maritime security vessel protection policies compared. New York: Springer International Publishing.

Cutler, D. (2019) From the sea to the c-suite: lessons learned from the bridge to the corner office. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Dedekorkut-Howes, A., Torabi, E. and Howes, M. (2021) ‘Planning for a different kind of sea change: lessons from Australia for sea level rise and coastal flooding’, Climate Policy, 21(2), pp. 152-170.

Demirtas, O. and Karaca, M. (2020) A handbook of leadership styles. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars.

Deplano, R. and Tsagourias, K. (2021) Research methods in international law: a handbook. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Eden, L., Nielsen, B. and Verbeke, A. (2019) Research methods in international business. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Epstein, J. and Boone, J. (2022) ‘State leadership to strengthen family engagement programs’, Phi Delta Kappan, 103(7), pp. 8-13.

Frick, N. et al. (2021) ‘Manoeuvring through the stormy seas of digital transformation: the impact of empowering leadership on the AI readiness of enterprises’, Journal of Decision Systems, 30(2), pp. 235-258.

Gemeda, H. and Lee, J. (2020) ‘Leadership styles, work engagement, and outcomes among information and communications technology professionals: a cross-national study’, Heliyon, 6(4), pp. 4-11.

Grint, K. (2021) Mutiny and leadership. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grønmo, S. (2020) Social research methods qualitative quantitative and mixed-methods approaches. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Hennink, M., Hutter, I. and Bailey, A. (2020) Qualitative research methods. 2nd edn. SAGE.

Hunneman, T. et al. (2022) ‘The role of leadership 4.0 and harmonization as a determinant of employee performance’, Webology, 19(1), pp. 258-270.

Kuehn, J. (2022) ‘Zumwalt, Holloway, and the Soviet Navy threat leadership in a time of strategic, social, and cultural change’, Journal of Advanced Military Studies, 13(2), 7-11.

Lee, M., Idris, M. and Tuckey, M. (2019) ‘Supervisory coaching and performance feedback as mediators of the relationships between leadership styles, work engagement, and turnover intention’, Human Resource Development International, 22(3), pp. 257-282.

Lyubykh, S. et al. (2022) ‘A meta-analysis of leadership and workplace safety: examining relative importance, contextual contingencies, and methodological moderators’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(12), pp. 2149-2175.

Maritime and Coastguard Agency. (2020) Code of safe working practices for merchant seafarers: amendment number 5 of 2020. London: Stationery Office

Mysirlaki, S. and Paraskeva, F. (2020), ‘Emotional intelligence and transformational leadership in virtual teams: lessons from MMOGs’, Leadership & Organisation Development Journal, 41(4), pp. 551-566.

Nilsson, R. and Saetre, S. (2021) Leadership at sea-leadership on-board according to experienced professionals and future maritime engineers.

Pak, K. and Desimone, M. (2019) ‘How do states implement college- and career-readiness standards: a distributed leadership analysis of standards-based reform’, Educational Administration Quarterly, 55(3), pp. 447–476.

Palmer, J. (2022) From bluegrass to blue water lessons in farm philosophy and navy leadership. Jarrell: Fidelis Publishing.

Pancasila, I., Haryono, S. and Sulistyo, B. (2020) ‘Effects of work motivation and leadership toward work satisfaction and employee performance: evidence from Indonesia’, Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(6), pp. 387-397.

Redford, D. (2020) Maritime history and identity: the sea and culture in the modern world. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Robinson, D. (2019) Twisting tide of leadership. Murrells Inlet: Covenant Books.

Robinson, V. and Gray, E. (2019) ‘What difference does school leadership make to student outcomes?’ Journal of the Royal Society of New Sealand, 49(2), pp.171-187.

Schram, C. and Aljaž. (2019) Handbook of research methods and applications in experimental economics. Hoboken: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Sebastian, L.C. and Chen, J. (2021) ‘Indonesia’s foreign and maritime policies under Joko Widodo: Domestic and external determinants’, Journal of Asian Security and International Affairs, 8(3), pp.287-303.

Shou, D. (2021) ‘All at sea: confronting exclusion in iBares’, The Leadership’ Metro Magasine: Media and Education Magasine, (207), pp.40-45.

Sluis, C. (2021) Leadership for risk management: navigating the haze with modern techniques. London: Springer.

Sulaiman, Y. (2019) ‘What threat? Leadership, strategic culture, and Indonesian foreign policy in the South China Sea’, Asian Politics and Policy, 11(4), pp.606-622.

Surabaya, K., Yulianti, P. and Erlando, A. (2022) ‘Tracking impact of leadership to creativity in Pt. Teluk Lamong: where are the moderation variables come from’, Journal Ilmiah, 6(2), pp. 1-16.

Symbaluk, D. (2019) Research methods: exploring the social world in Canadian contexts. 2nd edn. Toronto: Canadian Scholars.

Thomson, H. (2021) It’s not always right to be right. Hoboken: John Wiley.

Tracy, J. (2019) Qualitative research methods: collecting evidence crafting analysis communicating impact. 2nd edn. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell.

United Nations. (2021) Review of maritime transport 2020. New York: United Nations.

Wolor, C. et al. (2020) ‘Effectiveness of e-training, e-leadership, and work life balance on employee performance during COVID-19’, Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(10), pp. 1-8.

Wray, R. et al. (2021) Saltwater leadership a primer on leadership for the sea services. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.