Leonardo da Vinci, an Italian polyhistor of the great renaissance age, is generally regarded as one of the most gifted painters of his time. He was born on 14/15 April 1452 in Florence, Italy, and died in 1519 in France. In his early life, da Vinci was enlightened in the workshop of the prominent Italian artist, Andrea del Verrocchio. Although he had no recognized training, Leonardo’s paintings exemplified the Renaissance humanist notion and notes of science and innovation with such subjects as anatomy, cartography, painting, and botany. Whereas his prominence primarily relied on his accomplishments as a portraitist, scholars deduce his interpretation of the world as being founded on reasoning and rationality. To understand da Vinci’s fame and unique artistic works, an examination of his period, region, and painting style is essential.

The renaissance period formed a major part of the development of Leonardo’s artistic works. Several unique techniques were used to display orthodox paintings depicting art improvements with restrained beauty and science concepts. Da Vinci fashioned his artistic works in a diversity of media, thus earning desirable status in history. Leonardo’s creation and painting were analytical and precise (Keshelava, 2020). He experimented with a new technique of formulating and mixing colors. Instead of using specific colors, he blended them with oil to produce contrasting bright and light shades in his painting.

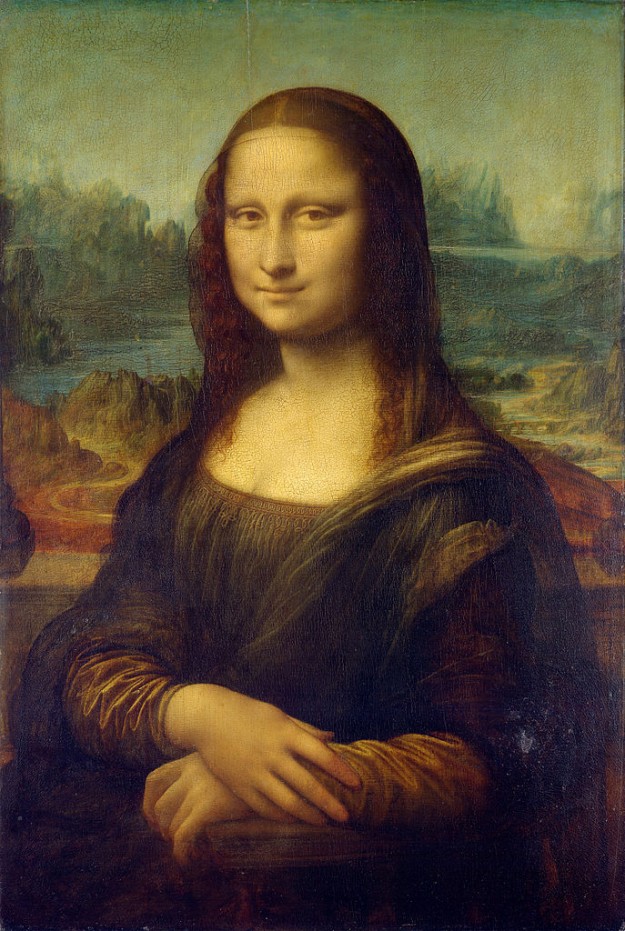

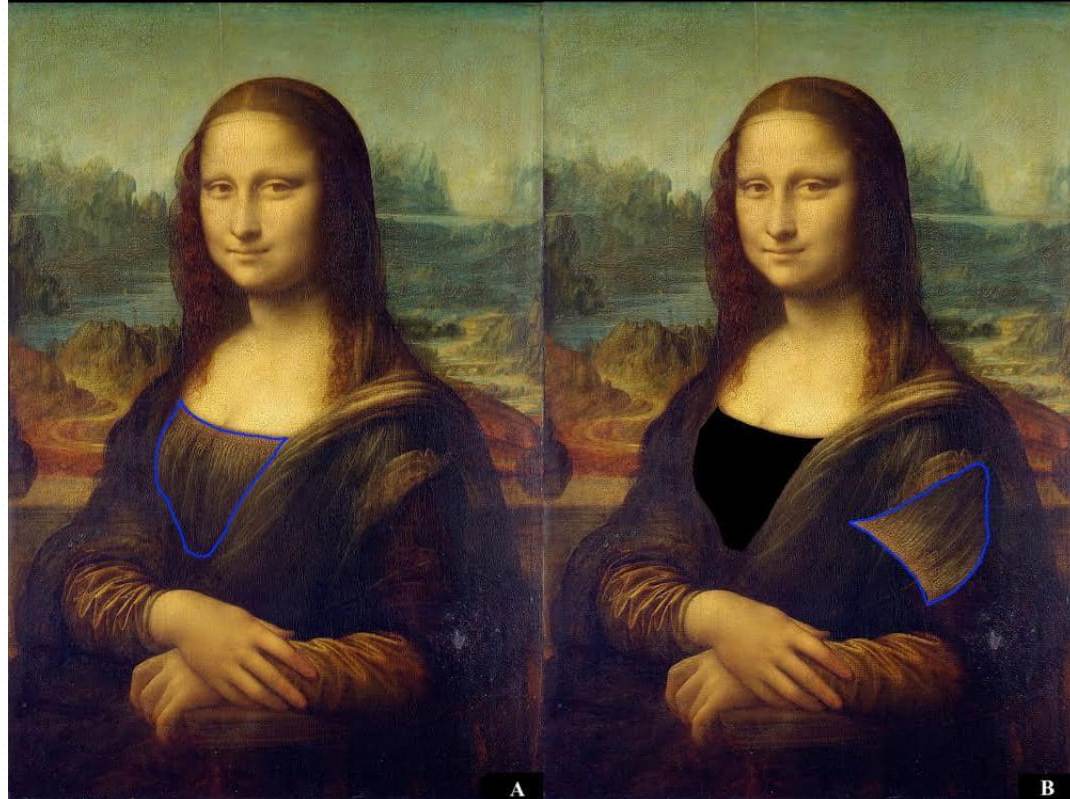

A classic example of his work was the painting of Mona Lisa also referred to as La Joconde. The portrait (see Figure 1) is an image of the Mona Lisa with a dimension of 3.2 X 5.17 inches with an endorsed date of 1503-1506. In this painting, da Vinci depicted a classical and elegant woman. He used the Sfumato technique, a blurring procedure that splits shades of dark and light to make the painting more accurate (Isaacson, 2017). Moreover, da Vinci used the trail of blue marked detail movement in Mona Lisa’s portrait (see Figure 2) to depict a woman wearing an Asian chador and a veil as can be seen in Figure 3). Precisely, La Joconde was not the convectional Italian representation of all women, as she described a more content character with a secure appearance, an anticipation of the dignity among men in the High Renaissance age.

The painting was also an illustration of the therapeutic illness that the Mona Lisa was suffering. For instance, de Vinci utilizes the Sfumato technique to validate how light ricochets off her skin while departing from other parts with darker oblivions making the skin appear real, though plausibly impractical to the observers. This technique portrays the presence of a “smile” and the science behind it (Isaacson, 2017). Besides, Mona Lisa’s absence of eyebrows with the swelling of the dorsum of the right arm, and a pale-yellow skin tone was indicative of lipoma or other more complicated symptoms of goiter (Mehra & Campbell, 2018). Therefore, Leonardo’s painting was more educational during the renaissance era, rather than only a depiction of beauty, nobility, and naturalism.

In conclusion, Leonardo da Vinci used the Sfumato technique during the High Renaissance in his artistic works by producing beautiful artworks guided by contemptuous themes of splendor, belief, naturalism, and idiosyncrasy. The artistic works he left behind motivate society and several generations. Through his work, da Vinci became the core value of the High Renaissance era since the beauty of art influenced all of his paintings and drawing works. For instance, Leonardo’s paintings were analytical with shades of dark and bright contours using the Sfumato technique because he believed that light and darkness were more naturalistic and factual.

References

Isaacson, W. (2017). The Science behind Mona Lisa’s smile: How Leonardo da Vinci engineered the world’s most famous painting. The Atlantic. Web.

Keshelava, G. (2020). Analysis of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa del Giocondo. International Journal of Health Sciences, 8(3), 17−20. Web.

Mehra, M. & Campbell, H. (2018). The Mona Lisa decrypted: Allure of an imperfect reality. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 93(9), 1325−1327. Web.