Introduction

The Internet has become an inherent constituent of modern life, to which people are exposed from early childhood. Almost every child is expected to have a smartphone in the future. The Internet permeates every aspect of life – work, education, communication, entertainment, and many others. The web contains content ranging from text and images to complex, massive databases. Millions of people are connected by social networks, which transcend national boundaries. All of these elements comprise a large cyber space, the role of which in life becomes more and more prominent. As more and more content is created, the dependency of people on the Internet becomes greater.

It is evident that contemporary and future generations have to possess the skills to work with cyber space. It can be debated whether the Internet will supplant paper-based sources of information, but everyone has to adapt to its presence. This necessity also applies to children who are born into the unprecedentedly interconnected world. Cyber space is a venue for communication, work, and entertainment even when physical interaction is limited (Edwards, 2021). Therefore, acquaintance with cyber space is an evident part of modern education and upbringing, which encompasses children in their earliest years.

As much as access to cyber space is a modern necessity, the Internet is also a source of danger for users of all ages. Whether the web is used for entertainment or educational purposes, it has the capacity to jeopardize the individual’s safety via multiple means ranging from the exposition of personal data to cyber-attacks and frauds. However, as much as the Internet is dangerous, it provides even more risks to children. Unable to understand the threats of cyberspace, children are especially susceptible to the danger. The lower the age is, the less protected they are, with age 0 to 6 being the most vulnerable (Straker et al., 2018). Understanding what constitutes risks to young children’s cyber safety is essential in understanding what prevention measures are the most appropriate.

The necessity for cyber protection is common knowledge, yet scientific input is necessary to understand the full extent of threats towards users. The issue is further complicated by the age of the target group, which has the upper limit of six years. This group demands greater attention and control from adults than any other age category because of the accessibility of the Internet and lack of knowledge and skills to protect themselves. Therefore, the search parameters should be limited to the sources, which study cyber threats towards children younger than six years specifically. The goal of this paper is to analyze the existing research on the risks cyber space poses to young children in order to ascertain the proper prevention measures, which would allow children to grow and learn the Internet safely.

Method

Best evidence synthesis was the main tool used to gather the necessary information. Due to the deficit of articles published on the topic of cyber safety specific to young children, the search was complicated by the absence of sources. Many articles study the subjective responses of young children and parents, which compromise the objectiveness of findings. The main challenge was classification of the data available in the articles from subjective to unbiased. Subsequently, all articles had to be analyzed and compared in order to uncover similar or different conclusions and ideas. As the Internet is the major platform, which provides valuable information for this assignment, the use of key terms was essential.

Search Procedure

The databases, which provided the scientific output are JSTOR, Education Resources Information Center, and Wiley Online Library database. Primary search terms were “young children”, “early childhood education”, “Internet exposure”, “cybercitizen”, “cyber safety”, “internet safety”, digital ethics”, “cyber ethics”, and “cyber hygiene”. Before starting the search, two filters were applied in order to target the necessary articles. First, all sources had to be peer-reviewed, which would ensure scientific quality. Second, the date filter limited the search to publications posted between 2017 and 2021. The reason for this specific time frame lies in the rapid development of cyber space and the dynamics of young children’s exposure to the Internet, which requires more recent analyses.

Study Selection: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The ultimate goal is to describe the state of research in Early Childhood and Care research on cybersecurity, analyze their methods and participants, which would allow to ascertain the most appropriate protective measures for children in cyber space. As has already been mentioned, the first inclusion criterion was the date limit. The pull of articles is limited to the ones published after 2016. As the Internet is a highly dynamic technology, the specifics of users’ experience with it are also subject to change. As a result, information about cyber space quickly becomes outdated, which renders sources published more than five years ago irrelevant. The reviewed literature comprises exclusively peer-reviewed scholarly articles.

Also, articles had to study the problem of cyber security of young children. This premise necessitates two inclusion criteria, one of which is the presence of the Internet in the body of articles. The other one is the focus on children younger than eight years. This age group differs from the older children and adolescents, which results in different threats and protective measures. For example, unlike older children, toddlers are not able to identify a threat, which does not harm them physically (Levine et al., 2019). Therefore, mediating their gadget use is more important since they cannot do it on their own.

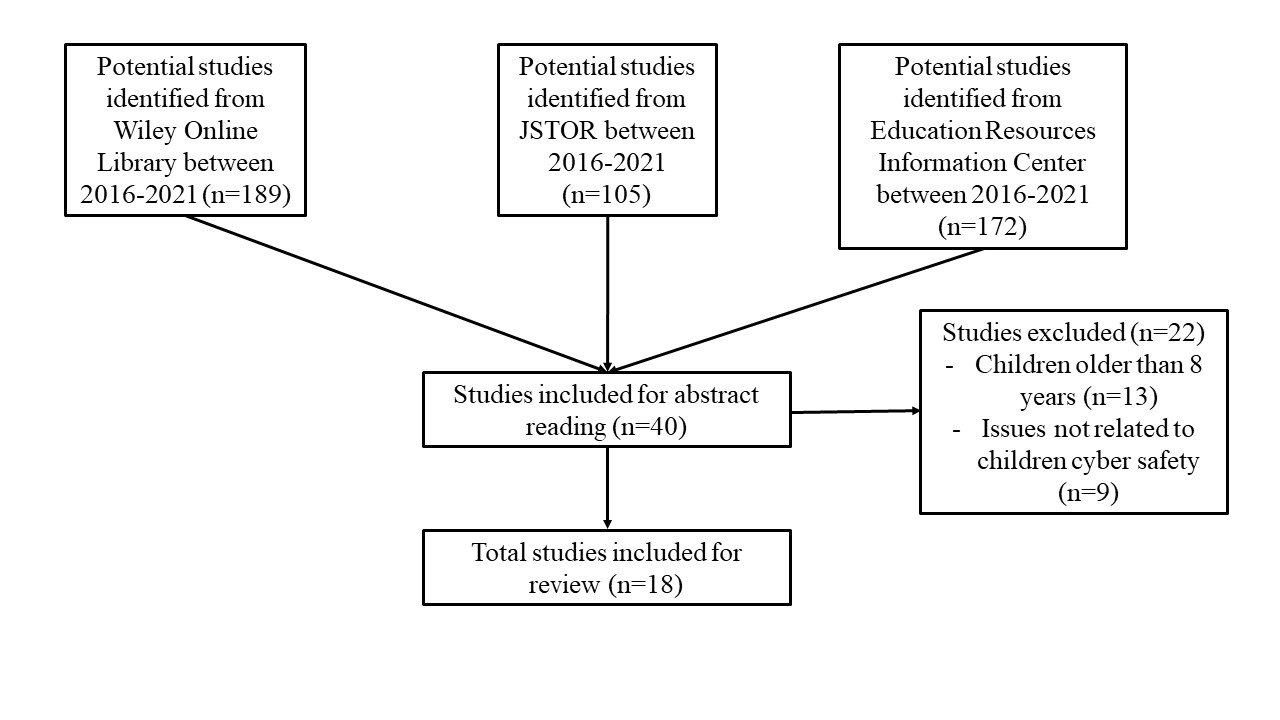

Naturally, some articles contain information on all age groups, including children below eight years. However, the conclusions presented by them apply to all groups indiscriminately. The issue of cyber bullying is deliberately excluded due to its irrelevance for the targeted age group. Combined together, these criteria form the exclusion basis for the multitude of available sources. The entirety of the procedure is visualized on the Flow Chart below.

Flow Chart

Results

e analysis of the articles provides information on the aspects related to the issues of cybersecurity pertaining to young children. Cybersecurity refers to the multitude of measures designed to protect users from the risks of the Internet and allow them to access the web safely. Young children are users of cyber space who lack the sufficient knowledge and skills to ensure their safety during their web interactions. Overall, five common themes are identified, which are the earlier age of Internet users, the increasing variety of risks, widening generation gap, insufficient parental mediation, and the necessity of teachers. The summary of the analyzed articles is available in Figure 1.

Earlier Age of Internet Users

The first theme across the articles is the gradually lowering age of Internet users. Edwards et al. (2018) argue that as more technology becomes available, there are more opportunities to utilize the gadgets. Young children may learn to use the gadgets even before they know how to speak. Naturally, their skills do not include the high-functional use of smartphones and computers. Yet, they are able to access the Internet at a relatively early age.

Moreover, they use smartphones in bedrooms and environments, presupposing their privacy, which subsequently means the lack of control. Interestingly enough, the fact that children consciously or unconsciously hide their usage of the Internet from their parents also indicates the development of independence. Sweeney et al. (2019) mention that children do not seek parents’ advice when encountering technical obstacles or errors but rather attempt to resolve the problems on their own. While it may be a positive tendency, it is also indicative of social isolation, which is also discussed by Poulain et al. (2018).

The earlier a child is exposed to cyber space, the greater is the chance of their addiction to the Internet (Levine et al., 2019). Janek (2019) wrote that “children’s digital device usage starts earlier year by year” (p. 159). If in 2009, the average start age was four, now it is expected that a child of his age is already familiar with the technology. Mostly, children of this age are used to touch screen experiences. This implies that their choice of electronics is usually smartphones and tablets. Fewer children interact with laptops and actual computers, which leads to greater eyesight problems, as indicated by Denic et al. (2017) and Andrews et al. (2020). Naturally, computer monitors also cause eye fatigue, but at least their size forces the eyes to move more often when compared to smaller screens (Hariyadi, 2020). As a result, not only do children get acquainted with cyber space earlier, but they compromise their eyesight earlier.

Classification of Risks

There is a consensus among studies that the Internet is a source of risks for children. Yet, the exact nature of the dangers is, in reality, multivariate. Although cyber space is a product of technology, it has implications far beyond the virtual environment. Therefore, the risks of the Internet are also diverse and comprise different spheres of children’s life. The literature authors also acknowledge it, with some authors, such as Bozzola et al. (2018), focusing more on technical aspects, while other researchers, such as Palaiologou (2017), emphasize physical and social issues. Even though these risks may seem not relevant to the Internet, they are directly caused by it. A child may feel anxious in real life precisely because they have encountered disturbing content on the web.

Technical issues regarding privacy for young children are not different from any other age group. The Internet treats all users indiscriminately (Görzig & Holloway, 2019). Regardless of whether it is a five-year old child, a mature adult, or a senior person in their sixties, all of them can encounter malicious programs while surfing the web. Viruses can damage the software, expose personal data, and transmit sensitive information to third parties. What makes this possibility especially risky when young children are concerned is the fact that these threats are virtual (Muir & Joinson, 2020). They cannot be observed by the human eye, sensed, or heard. Yet, physical sensations are essential in children’s learning of threats and dangers (Lazarinis et al., 2020). As a result, children are not aware of the consequences of visiting a website with no certificate or downloading an untrusted app.

Physical problems are also intrinsically related to Internet overuse. Cyber space is extremely engaging and addictive, which leads to many mature adults losing self-control and spending an excessive amount of time with gadgets. This problem is even worse with young children, whose minds are not disciplined enough to exercise self-control and know when to stop (Edwards et al., 2017). As a consequence, children also spend enormous time interacting in cyber space. The human body is not built for continuous usage of screens. Children’s organisms are still in development when they first encounter gadgets. Therefore, the utilization of electronics has an especially adverse effect on them (Palaiologou, 2017). Health problems originating with addiction to cyber space include damaged eyesight, back aching, general lack of motion, blood circulation, and other serious conditions (Denic et al., 2020). When children direct their exploratory energy to cyber space exclusively, they compromise their physical health and development.

Social issues may also arise from the excessive use of gadgets and the Internet. The first years in a child’s life are essential in the formation of their communicative abilities. The Internet may create the illusion of communication via the interaction with voice search services, such as Google Assistant, but it does not substitute real-life interactions with people (Poulain et al., 2018). A child has to listen to a human voice, understand gestures, recognize mimics, engage their sensors in order to learn interpersonal communication (Danovitch, 2019). These aspects are subtle, yet these subtleties are extremely important. If a child spends their time playing virtual games instead, they will hinder their own development and create social problems in the future (Rahman et al., 2020).

Rising Disparities between the Generations

Some studies suggest the idea of the striking differences between modern parents and their offsprings. When parents stop using their smartphones, they pass them to their children. Contemporary adults did not grow with smartphones, tablets, and the Internet easily available. Therefore, there is a substantial difference between the current generation and younger generations. Due to the abundance of technology present, young children are introduced very early to the Internet. Several studies report about four-year old children being aware of Wi-Fi, downloading process, messengers, and other concepts.

Children are also aware of popular platforms, such as YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and other ones (Edwards, 2021; Straker et al., 2018). It may not seem as impressive, yet Janek (2019) writes some of the observed children had no access to gadgets at all. It can be explained by the children being passive users, which manifests in them observing their parents and other children use the devices but not actually doing it themselves.

None of these developments were evident when contemporary adults were in childhood. Information technologies were introduced gradually with a certain degree of cautiousness. In contrast, today’s children learn them almost from the start. It creates a difference in attitudes towards cyber space between the generations (Poulain et al., 2018). Whereas parents know about the virtual dangers and think first of safety, children view the Internet as an endlessly positive experience. It does, after all, allow them to play the games they like, watch the videos they desire and seek any information they need. As a result, children unconsciously believe in the inherent positivity of the Internet (Oliemat et al., 2017). This belief cannot be easily overridden by parents’ and teachers’ warnings and instructions.

It is too early to state that this conflict of beliefs will result in negative repercussions. However, it does create a rift between children who seek more virtual experiences and parents who want to limit them for their offsprings (Sweeney et al., 2019). Some researchers believe that it is a normal development because contemporary children are more tech-savvy and will feel more confident in the virtual environment in the future (Arnott et al., 2018). Others express the concern that childhood-driven belief in the positivity of cyber space forces children to underestimate the negative aspect of the Internet (Denic et al., 2017). In either case, the availability of means to access cyber space widens the generational gap.

Parental Mediation

The fourth common theme is the lack of control of children’s web activities by parents. Sweeney et al. (2019) report that sixty percent of the children they studied did not talk about any regulations set by parents. Considering that all children in that study were eight years old, there is a definite lack of concern from the parents. Yet, Hariyadi (2020), who studied toddlers, reports a simial finding. Levine et al. (2019) also note that parental regulation of young children’s activities is either inadequate or non-existent.

The way the family regulates the overall conduct of children is important. Parental control is not necessarily limited to the regulation of children’s use of the Internet. In a similar way to previous generations, who were not exposed to the Internet, children were also restricted from engaging in entertainment (Sweeney et al., 2019). In the case of the past generations, the restricted activity was watching TV. Now, it is supplanted by Internet surfing and overall gadget use. However, the fact of excessive time spent while using smartphones is not the prime motive behind parental motivation (Muir & Joinson, 2020). As a result, the degree of restrictions depends on the general level of the family’s strictness and rules. The more restrictive parents generally are, the less their children are exposed to the dangers of the Internet.

The most commonly technically used method of controlling children’s actions is via filters (Edwards et al., 2018). Technology enables parents to customize their children’s web experiences. For instance, they can install software, which blocks access to certain websites and services. A more extreme variation is the restriction of time spent while using the gadgets overall. Some parents use such apps as Google Family Link, which provide them with live data on the presence of a child, the amount of time they spent on the Internet, and the apps they use (Oliemat, 2018). Such services facilitate familial control and parental mediation.

Necessity of Teacher in Cyber Safety

Cyber education is an important stage of overall personal development in the modern world. Even the tech-savvy contemporary adults have undergone a stage of life where cyber space was perceived as an unknown and possibly dangerous virtual environment. However, today’s adults had more life and technological experience when they first encountered the Internet. The same cannot be stated about modern young children, who have no such experience to help them get acquainted with cyber space (Straker et al., 2018). The virtual environment is a complex concept in itself, yet it is even more challenging to understand when attempting to explain it to children. Edwards et al. (2018) note that the majority of children had no conception of the Internet’s whereabouts. For instance, they could not understand that when they write a post, it can be read by any user on the same social network.

Studies express the viewpoint that such ignorance should be managed by cyber education (Görzig & Holloway, 2019; Oliemat, 2018; Bozzola et al., 2018). The earlier children learn the concept of the Internet, the easier they will adapt in later life (Muir & Joinson, 2020). A natural curiosity drives children to explore their surroundings, including the content of smartphones. Such actions can lead to them accessing age-inappropriate content, unintended sharing of personal data, and even unplanned purchases. These possibilities constitute the necessity for education on the Internet’s dangers (Andrews et al., 2017). Although removing access to electronics is an option, it does not resolve the larger problem, which is the ability to identify risks in cyber space.

Many researchers express the same idea that cyber education should be designed on associative learning. It refers to a technique, which groups existing knowledge and facilitates further learning by relating the new knowledge to the knowledge stored in memory (Danovitch, 2019). As it is the most efficient way of memorizing words and understanding concepts for young children, the Internet should not be an exception. The human mind processes all information and compares it to the knowledge stored in memory. Adults do not realize it because of the years of accumulated knowledge (Rahman, 2020). At the same time, children’s minds are not filled with knowledge. Subsequently, they are less distracted compared to adults. Therefore, it is essential to create associations with the objects, and concepts children already know. For instance, teachers can use some app, which are familiar to a child, and explain important functions and consequences using this app as an example (Broekman, 2018). The same approach can also be applied to the Internet and social networks.

Studies suggest that cyber education should have a more practical direction. For instance, children should learn to protect their accounts with secure passwords, which should not be relayed to anyone (Denic et al., 2017). For the purpose of avoiding virtual viruses, parents can teach the children to avoid untrusted connection when the corresponding message appears on the screen (Edwards et al., 2018). Most importantly, children should learn as soon as possible that any disclosure of personal information at someone’s request is dangerous and should be avoided (Görzig & Holloway, 2019). These are the essential steps in teaching preschoolers cyber safety.

Discussion and Conclusions

The analysis of the literature has showcased four major themes. First, cyber space contains a plethora of risks to young children. They include technical issues, such as computer viruses and malicious programs, which may compromise personal data (Görzig & Holloway, 2019). Another risk is the physical implications of prolonged exposure to cyber space (Palaiologou, 2017; Edwards et al., 2017). Due to the design of the electronics, which enable users to access cyber space, people are forced to spend a large amount of time in positions, which damage eyesight, posture and limit motion. Finally, the virtual environment creates the illusion of communication, while the actual social interactions are sacrificed (Poulain et al., 2018; Danovitch, 2019). As a result, young children fail to accumulate important communicative skills because all their energy is spent while utilizing the gadgets (Rahman et al., 2020).

The second theme evident from the research is the lowering of first contact age. Contemporary young children are expected to have some experience with smartphones and the Internet (Straker et al., 2018). The engaging nature of gadgets makes them a quick and efficient way to occupy children. On the one hand, early exposure facilitates the adaptation to virtual communication, which is inevitable (Edwards, 2021). On the other hand, it creates a possibility of young children’s greater dependency on electronics and deeper addiction to cyber space (Poulain et al., 2018; Palaiologou, 2017). In both cases, cyber space will play a much wider role in contemporary young children’s lives than in their parents’ ones.

This leads to the rising discrepancies between the generations, which is the third theme. Exposure to cyber space delineates the current young children as the first generation to get acquainted with the Internet before they are able to talk (Janek, 2019). Subsequently, the new generation will probably have a more positive outlook on the Internet and cyber space, which may also lower their attention towards the cyber space threats (Oliemat, 2018). It is reasonable to suggest that in ten years when current young children will enter their adolescence, the trustworthiness of the Internet will be a highly contentious point between them and older generations (Edwards et al., 2018).

The logical solution to the problem of excessive exposure to cyber space is parental mediation, which is also the fourth theme. Researchers note that there are different approaches to the restriction of children’s time spent in cyber space (Oliemat, 2018; Broekman et al., 2018; Danovitch, 2019). They range from overall familial rules to software blocks, which prevent the use altogether. Whatever method is used, researchers agree that parents’ role is crucial in cyber space upbringing (Denic et al., 2017; Bozzola et al., 2018; Arnott et al., 2018). Modern applications make parental control easier and protect children from inappropriate content and actions.

However, parental mediation should be accompanied by overall cyber space education, the necessity of which constitutes the fifth and final theme. Associative learning can help teachers explain complex topics to young children (Danovitch, 2019). Furthermore, they will educate them on the threats and risks, which are essential to know while operating on cyber space (Andrews et al., 2020). Proper education can alleviate future problems and anxieties by informing the children about such possibilities beforehand (Bozzola et al., 2018). It is evident that the Internet will be a constant companion in their future lives, thus, they should also learn to protect themselves from its dangers.

The main discovery this analysis makes is that parents underestimate the severity of cyber space risks to their children. Some studies definitely showcase parents who take the problem of early exposure to the Internet seriously (Poulain et al., 2018; Oliemat, 2018. Danovitch, 2019). However, more studies indicate that an alarming number of adults do not regulate their children’s use of the Internet at all (Denic et al., 2017; Hariyadi, 2020; Janek, 2019; Levine et al., 2019; Muir & Joinson, 2020; Rahman et al., 2020). Most likely, this degree of ignorance is attributed to the fact that parents acquainted themselves with the Internet when they were mature enough to understand the risks, which prevents them from empathizing with children (Poulain et al., 2018). Another explanation is that parents do not believe that preschool children are not yet capable of using gadgets and the Internet to inflict damage (Hariyadi, 2020). Ultimately, the real reason for parents’ ignorance is not established, as researchers focus on young children and their cyber education.

Limitations and Further Research

The major limitation behind this review is the dependency on the sample populations of the researchers. As all studies base their conclusions on the analyses of a limited number of respondents, there is a chance that the samples do not really represent the larger population. Subsequently, the themes ascertained may certainly be applied to the children, which were analyzed by the studies included in this review. Considering that the majority of the children are American, the specifics of other nationalities remain unknown. Although it is likely, that similar conclusions can be extrapolated to them as cyber space is pervasive and equally affect young children in any part of the world.

Many studies emphasized the generation gap between parents and children due to cyber space. Yet, the exact nature of such discrepancies remains an open question. Parents and children have always differed from each other, yet the rapid advancement of technologies changes life drastically. At no point in history did people have as much access to knowledge as they do now (Edwards, 2021). The subsequent question is whether the current situation is unique and what was done to minimize the risk from new technologies to young children in the past. Understanding the efforts of past generations may help protect contemporary children from the dangers of cyber space.

Another idea expressed by many researchers is the necessity of cyber space education. Yet, the virtual environment is relatively new, and people do not have experience teaching their children how to properly work with such technology (Levine et al., 2019; Lazarinis et al., 2020). Possible future research can analyze the past educational efforts when new sources of information were available. For instance, widespread literacy is a relatively new historical phenomenon. At some point, parents were forced to acknowledge the importance of books in education, similar to how they are forced to acknowledge the importance of cyber space now. Maybe historic educational adaptation to books will provide insight into how to educate children on the Internet and increase their cyber safety.

References

Andrews, D., Alathur, S., & Chetty, N. (2020). International efforts for children online safety: A survey. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 16(2), 123-133. Web.

Arnott, L, Palaiologou, I, Gray, C (2018) Digital devices, internet-enabled toys and digital games: The changing nature of young children’s learning ecologies, experiences and pedagogies. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(5): 803–806.

Bozzola, E., Spina, G., Ruggiero, M., Memo, L., Agostiniani, R., Bozzola, M., Corsello, G., & Villani, A. (2018). Media devices in pre-school children: The recommendations of the Italian pediatric society. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 44(1), 1-5. Web.

Broekman, F. L., Piotrowski, J. T., Beentjes, H. W., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2018). App features that fulfill parents’ needs in apps for children. Mobile Media & Communication, 6(3), 367-389. Web.

Danovitch, J. H. (2019). Growing up with Google: How children’s understanding and use of internet‐based devices relates to cognitive development. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 1(2), 81-90. Web.

Denic, N., Nesic, Z., Radojicic, M., Petković, D., & Stevanović, M. (2017). A contribution to the research of children protection in use of internet. Tehnicki Vjesnik, 24(2), 525-533. Web.

Edwards, S. (2021). Cyber-safety and COVID-19 in the early years: A research agenda. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 1-12. Web.

Edwards, S., Nolan, A., Henderson, M., Mantilla, A., Plowman, L., & Skouteris, H. (2018). Young children’s everyday concepts of the internet: A platform for cyber‐safety education in the early years. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(1), 45-55. Web.

Görzig, A., & Holloway, D. (2019). Internet use. The Encyclopedia of Child and Adolescent Development, 1-10. Web.

Hariyadi, B., Yuniarno, S., & Dardjito, E. (2020). Mother’s perspective about using the gadget safeness for children. Jurnal Pendidikan Usia Dini, 14(2), 313-320. Web.

Janek, N. (2019). From touch to click–online presence and internet usage between the ages of 4 and 7. Létünk, 49(1), 157-187.

Lazarinis, F., Alexandri, K., Panagiotakopoulos, C., & Verykios, V. S. (2020). Sensitizing young children on internet addiction and online safety risks through storytelling in a mobile application. Education and Information Technologies, 25(1), 163-174. Web.

Levine, L. E., Waite, B. M., Bowman, L. L., & Kachinsky, K. (2019). Mobile media use by infants and toddlers. Computers in Human Behavior, 94, 92-99. Web.

Muir, K., & Joinson, A. (2020). An exploratory study into the negotiation of cyber-security within the family home. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 424, 1-14. Web.

Oliemat, E., Ihmeideh, F., & Alkhawaldeh, M. (2018). The use of touch-screen tablets in early childhood: Children’s knowledge, skills, and attitudes towards tablet technology. Children and Youth Services Review, 88, 591-597. Web.

Palaiologou, I. (2017). Digital violence and children under five: The Phantom Menace within digital homes of the 21st century?. Education Sciences & Society-Open Access, 8(1), 123-136.

Poulain, T., Vogel, M., Neef, M., Abicht, F., Hilbert, A., Genuneit, J., Körner, A., & Kiess, W. (2018). Reciprocal associations between electronic media use and behavioral difficulties in preschoolers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(4), 1-13. Web.

Rahman, N., Sairi, I., Zizi, N., & Khalid, F. (2020). The importance of cybersecurity education in school. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 10(5), 378-382. Web.

Straker, L., Zabatiero, J., Danby, S., Thorpe, K., & Edwards, S. (2018). Conflicting guidelines on young children’s screen time and use of digital technology create policy and practice dilemmas. The Journal of Pediatrics, 202, 300-303. Web.

Sweeney, T. A., Georg, S. M., & Ben, F. (2019). Home Internet use by eight-year-old children. Australian Educational Computing, 34(1), 1-22.