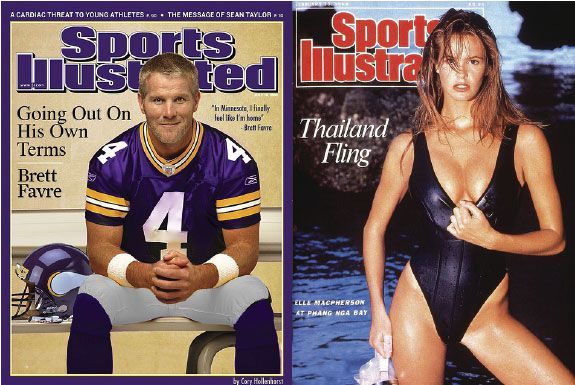

Women are misrepresented and underrepresented in the existing news media. Around the world, they are featured far less than men are, being invited to interviews as experts only in 13% of cases, while constituting only 37% of the reporter base (Rattan). These facts alone are evidence enough of underrepresentation, but even those professionals being featured help perpetrate a gender-stereotypical agenda. Davis (2) reports that the content analysis of Instagram sites dedicated to fitness shows a keen difference between how men and women are represented. The amount of sexualized content involving college-age women is notoriously higher than that of men (Davis 2). This creates the image of a woman as that of an inherently sexual and “available” creature. At the same time, sports pictures show men in active, “dynamic” roles, whereas pictures of women are static and associated with passivity (Davis 2). This type of misrepresentation paints the traditional role of a submissive and weak female along with the dominant and initiative male.

Finally, there is the issue of further misrepresenting female and enforcing stereotypes by choosing gender-specific colors, products, and imagery. While men’s section is filled with news and prompts about engineering, IT, stocks, cars, and travel, women’s sections in most newspapers seems to be focused on the “traditional” gender-specific activities – beauty, gossip, fashion, cooking, and so forth (Davis 4). Doing so not only paints a heteronormative and role-specific model, but also eliminates a good number of female experts in many other areas from the potential interviewing pool.

Fixing this misrepresentation would go a long way to fixing the injustices and oppression that is exerted by the weakening patriarchy over the rising women. It will allow young girls to dream of being something other than eye-candy in their youth and nobodies in their senior years. There are several potential solutions that could help with this endeavor. The first one has been exhibited by the BBC, which achieved 50-50 gender parity among their reporters (Rattan). Such a bold move proved to be an achievable success and should be followed by other media outlets. Additional solutions could include the reduction of sexualization for women, featuring them in normal clothes and body shapes, without the gloss and purposeful picturing of all women as attractive objects to be obtained and strived for.

Finally, male and female columns should be dismantled in the favor of gender-neutral columns that portray both genders performing equally. Alternatively, the media should feature more information about women making headway in the areas previously considered to be “men’s turf,” such as sports, engineering, IT, military, politics, and so forth. Doing so would influence many young women that trying to find themselves in these areas is not only socially acceptable, but encouraged. Doing so would increase the number of female experts in all areas, help reduce the wealth gap, and promote a more equal and egalitarian society. To further facilitate these ends, media outlets should make a conscious effort to seek out the rare (for now) female experts to give interviews. Many newspapers and information agencies do not seek out these women simply because it’s easier and more convenient to find a male. They should, instead, go through the extra effort to reduce misrepresentation. Female experts may have insights that are not often covered by sharing their experience both as professionals and as women, bringing further light to male-female relationships in the workplace.

Works Cited

Davis, Stefanie E. “Objectification, Sexualization, and Misrepresentation: Social Media and the College Experience.” Social Media + Society, vol. 4, no. 3, 2018, pp. 1-9.

Rattan, Aneeta et al. “Tackling the Underrepresentation of Women in Media.” Harvard Business Review, 2019. Web.