Introduction

Emergency management is a sphere of vital importance for contemporary society due to the nature of the problems it aims to address. Today’s world can be characterized by the increased level of uncertainty within large-scale processes, which have rendered the global landscape unpredictable to a substantial degree. The range of threats faced by modern communities is vast, and it continues to expand across years and decades. As such, humanity has been subject to natural disasters of immense magnitude since the dawn of history. Despite the recent advancements, technological means remain unable to counteract the destructive potential of the elements. Furthermore, technology per se is a strong enabler of disastrous humanmade events, which threaten even the most advanced nations. As constructions and mechanisms continuously grow in terms of size and complexity, so does the possibility of malfunctioning, which is capable of entailing adverse consequences. Finally, the ideas of uncertainty are strongly related to the infamous threat in the form of international and domestic terrorism, menacing the entire world.

These challenges form an area of increased concern for global communities and policy-makers. Accordingly, significant recourses and assets are allocated in order to address the problem at all levels. Nevertheless, while strategic resolutions remain a matter of pivotal importance, it is the direct response to such challenges that has earned a particularly vital status. Whatever the underlying issues behind a disaster may be, its occurrence is to be addressed with due diligence, efficiency, and caution. The response protocols are executed by diverse teams of multiple units that are expected to work in the spirit of interprofessional cooperation and understanding. Therefore, organizing such units is a challenging task, which requires strong, educated leadership. Emergency managers have to demonstrate the level of decisiveness and inner strength adequate to the magnitude of a disaster. Moreover, these crises often unfold at a rapid pace, adding a rush element to the already unpredictable situation. Therefore, efficient yet correct decision-making is an absolutely indispensable characteristic of a strong leader in emergency management.

While the sphere demonstrates an array of particularities, which make it sufficiently different from the majority of industries, it is still possible to review within the framework of universally accepted paradigms. However, even though some theories and approaches may stem from the areas of public business and leadership, many of them acquire a different form in law enforcement, military operations, and emergency management. In other words, the universal principles of leadership and effective decision-making cannot be transferred to the domain of emergency management without certain necessary adjustments. These alterations serve to reflect the indeterminacy, changeability, and risks, which are constantly present in disaster and terrorism response. At the same time, as the discipline is constantly evolving, the institute of emergency leadership philosophy undergoes similar changes dictated by the essence of the new age. In the era of new international challenges, the leading minds of emergency management have become concerned with the necessity to redefine the field’s principles of decision-making. This paper aims to contrast the two leading frameworks in this regard, the OODA Loop and CECA, in terms of their adaptation to the current changeable environment.

Review of Literature

In order to discuss the applicability of a certain decision-making paradigm within the framework of emergency response, it is important to consult the existing sources of valuable academic data. As a matter of fact, effective decision-making in the stressful environment of emergency response can be viewed as one of the key aspects of the professional sphere. The purpose of the current literature review is to collect contemporary information regarding the status of decision-making in emergency management and response, as well as its key principles within the area of study. First of all, as can be inferred from the nature of the mission, emergency response deals with rapidly unfolding occurrences, demonstrating elevated damage risks (Glarum & Adrianopoli, 2019). Furthermore, while the field, in general, possesses its distinctive features, the array of humanmade, natural, and terrorism-associated threats show a high degree of variability. As such, Glarum and Adrianopoli (2019) confirm that there is not a universal solution that would fit all situations within emergency response objectives. Accordingly, this idea implies that the optimal paradigm of decision-making for emergency management is expected to be sufficiently versatile.

At the same time, emergency response teams tend to be organized in accordance with a strictly structured hierarchy, which promotes the ability of a unit to follow the leadership’s commands. While the majority of the world’s industries sway toward more democratic systems of leadership, the sphere of emergency management has been unable to follow the general pattern due to the immense value of subordination in such a changeable and stressful environment. Nevertheless, while the authority of leadership in this sector tends to be significantly higher, sensemaking remains an important component of it (Glarum & Adrianopoli, 2019). In other words, while emergency responders in the field are expected to follow the commands they receive from the control center, it is highly important for them to understand the context and the purpose of the designated tasks. According to Schildt et al. (2019), there exists a nexus between the power of the leadership and the sensemaking potential of a situation. Systemic power is met with a higher degree of respect, thus contributing to the sensemaking process within units. On the contrary, the lack thereof negatively affects a team’s ability to see the complete picture.

Overall, the operations within the sphere of emergency management are often filled with a large number of cases, in which it is required to make difficult decisions. For example, Hoekstra and Montz (2017) reviewed the decision-making process in disaster response based on the case study of Superstorm Sandy. Within this in-depth study, the emphasis was made on the internal processes experienced by leaders in the course of decision-making. As such, the interviewees have nearly unanimously pointed to the possibility of casualties as the key factor influencing their decision-making. In other words, the risks related to people’s lives hold the most weight in the practical environment, prevailing over infrastructural damage and economic aspects. The data presented by Poggi et al. (2021) equally outlines the costs of latency in data collection in decision-making in rapidly changing catastrophic scenarios. At the same time, this article refers to decision-making as one of the key enablers of community resilience and recovery. Accordingly, the optimal decision-making paradigm for emergency management is expected to consider the key notions outlined within the current literary space.

OODA

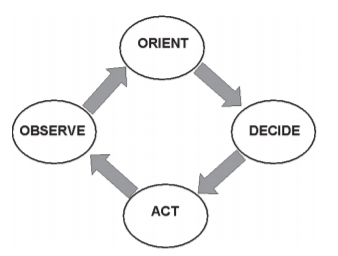

The OODA Loop has been one of the prominent decision-making techniques used across various spheres of human activities. However, the range of its application mostly comprises military organizations and similar structures. According to Bryant (2006), OODA is an acronym for Observe, Orient, Decide, Act, and this looped pattern serves to guide military decision-makers. Moreover, the OODA Loop was embedded in the United States Armed force doctrine. The utilization of the model on such a high level of national security is often viewed as one of the primary arguments in favor of its unconditional effectiveness. Generally, it comprises four basic stages, which are supposed to become the bridge between the broad conceptual framework and the tactical circumstances of a given situation. Bryant (2006) states that the OODA Loop is often considered to be intuitively accurate, meaning that its features inherently correspond to the nature of the task faced by military-like institutions. The emphasis of the is paradigm is on data gathering and informed decision-making. Nevertheless, despite the perceived effectiveness and the logic behind the framework, the number of its opponents has been on the increase in recent years.

CECA

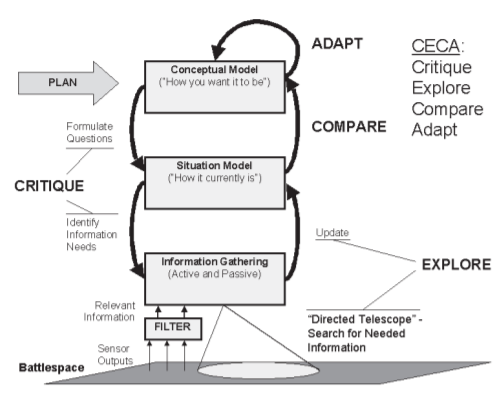

Ultimately, when the leading decision-making paradigm reveals its flaws through research and practice, the emergence of other promising avenues becomes a matter of time. CECA stands for Critique, Explore, Compare, Adapt, and it is an alternative loop used for the decision-making process in stressful environments. However, experts do not limit the applicability of the CECA framework solely to military-like structures, as “it is intended to serve as a framework for describing natural human cognition and discussing prescriptive measures for supporting command decision-making” (Bryant, 2006, pp. 191-192). This model relies on the initial outline of the conceptual framework completed by a decision-maker (Figure 2). Next, this outline is critically analyzed in terms of its relation to the presently observed situation. Once the degree of divergence has been estimated, the decision is to be made regarding how the situation can be affected in order to adjust it closer to the prior conceptual understanding. Therefore, the CECA model promotes an active approach to leadership and decision-making. It is highly goal-oriented, which corresponds to the requirements set by the context of emergency management.

Decision-Making Framework Analysis

Sensemaking

Both of the decision-making frameworks discussed in the previous sections have proven their effectiveness across years and different military operations. However, as suggested by the focus of the emergency management sphere, even the principles, which are widely applied in adjacent sectors, may not fully correspond to its missions and objectives. As such, it appears relevant and valuable to compare the two frameworks in the context of the emergency management features determined through the review of the literature.

First of all, sensemaking remains an important component of emergency management unit functioning. People who form the response teams pursue similar objectives, and they are expected to follow the leadership’s commands unconditionally. However, it is vital to ensure each member’s understanding of the specific ideas becomes each command or strategy. This way, the response will benefit from evidence-based, informed practices execute with due caution and attention (Weick, 1993). Both frameworks discussed within this paper rely on this aspect of emergency decision-making. The OODA Loop devotes a significant portion of its attention to observation and orientation in order to keep the practices informed. However, Rousseau and Breton (2004) observe the lack of the “feedback or feed-forward loops needed to effectively model dynamic decision-making” (p. 4). Therefore, the OODA Loop demonstrates decreased effectiveness in terms of sensemaking. On the other hand, the CECA framework has a higher potential in this regard, as the adaptive capability of the model renders it closer to the contemporary requirements.

The second key notion within the sphere of emergency management comprises the organization of role structures within units. This profession can be deemed military-like due to the strictly regulated nature of its protocols, as well as the need for a strong hierarchy. Both decision-making paradigms acknowledge such a necessity, granting the leader the theoretical power to give unconditional commands. Accordingly, both frameworks inherently expect the followers to accept and implement the decisions of their leaders (Bryant, 2006). Under such circumstances, the cost of an incorrect decision becomes higher, and, in the case of disaster and terrorism response, this parameter is measured in human lives. As suggested by research, the CECA loop demonstrates a better degree of decision-making flexibility, prompting leaders to consider more variables through the comparison of the conceptual framework and its current reflection. The OODA loop is rather obsolete in this regard, as its lack of agility may entail adverse consequences due to insufficient adaptation (Bryant, 2006). Therefore, the CECA model appears favorable in this area, as well.

Finally, in order to tackle global challenges, decision-making should create an atmosphere of trust within disaster response units. This feeling is crucial for stressful environments associated with increased pressure, rapidity, and changeability (Seddighi, 2020). People are often forced to push themselves beyond the limit of the impossible, which is only possible on the condition that they fully trust the leader in charger of key decisions. As controversial as a decision may seem, if the team trusts its manager, it will be more likely to follow the proposed strategy (Weick, 1993). As each unit is different in terms of values, objectives, and personalities which compose it, sufficient flexibility is required, as well. The CECA framework is generally associated with agile decision-making practices, making it instrumental in building trust within the team.

Implications and Conclusions

In the end, the decision-making framework utilized in relation to the challenges of emergency response should reflect the acute issues addressed by the sphere. As indicated by the contrast analysis of two prominent approaches, the CECA loop is much better adapted to the current environment. In fact, when discussing decision-making paradigms, Bryant (2006) mentioned the outdated mechanism of the OODA model, which eventually lost its status after years of prevalence in the military environment. Despite potential similarities between the army and emergency management, the latter requires even more agility in terms of decision-making. In fact, a considerable portion of the current indeterminacy is caused by global terrorist threats. As the response practices effectively interrupt terrorists’ activities, the latter attempt to devise new techniques and bypass the global security systems. As a result, the challenges posed by global and domestic terrorists constantly evolve, attacking the well-being and safety of communities from different angles. Therefore, the response mechanism should respond to this changeability by adopting an agile model of decision-making capable of adjusting the measures to particular threats. The CECA loop appears to be the optimal choice by the discussed set of parameters.

References

Bryant, D. J. (2006). Rethinking OODA: Toward a Modern Cognitive Framework of Command Decision Making. Military Psychology, 18(3), 183–206.

Glarum, J., & Adrianopoli, C. (2019). Decision making in emergency management. Butterworth-Heinemann.

Hoekstra, S., & Montz, B. (2017). Decisions under duress: Factors influencing emergency management decision making during Superstorm Sandy. Natural Hazards, 88, 453-471.

Poggi, V., Scaini, C., Moratto, L., Peressi, G., Comelli, P., Bragato, P. L., & Parolai, S. (2021). Rapid damage scenario assessment for earthquake emergency management. Disaster Seismological Research Letters.

Rousseau, R., & Breton, R. (2004, June). The M-OODA: A model incorporating control functions and teamwork in the OODA loop. In Proc. Command and Control Res, & Tech. Symp.

Schildt, H., Mantere, S., & Cornelissen, J. (2019). Power in sensemaking processes. Organization Studies, 41(2), 241-265.

Seddinghi, H. (2014). Trust in humanitarian aid from the earthquake in 2017 to covid-19 in Iran: A policy analysis. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 14(5), 7–10.

Weick, K. E. (1993). The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: the Mann Gulch disaster. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38(4), 628–628.