As of today, it became a commonplace assumption among many film-critics that the era of classical Noir films extends from the year 1941, which saw the release of John Huston’s film The Maltese Falcon, to the year 1958, when Orson Welles produced his movie Touch of Evil. Nevertheless, it was not up until 1946 that the term ‘Noir’ was first mentioned in French film magazines, regarding the crime-drama films that featured the motifs of existential alienation, socially inappropriate sexuality, moral ambivalence, perceptional cynicism, psychological inadequacy, along with the elements of the expressionist editing.

These elements included the spatial discontinuity between the takes/shots, the visual dramatization of contrasts between light and darkness, the presence of an off-screen narration, etc. According to Conard: “(Noir is) the inversion of traditional values and the loss of the meaning of things. That is, at the heart of the noir mood or tone of alienation, pessimism, and cynicism we find, on the one hand, the rejection or loss of clearly defined ethical values” (17).

Whereas the protagonists (most commonly police officers and private detectives) in the conventional crime-fiction movies of the era are represented as morally upstanding and rationale-driven individuals, committed to the cause of promoting the society’s betterment, a Noir protagonist acts in an altogether different manner. His main objective in life is to become emotionally comfortable with what he perceives as the clearly irrational ways of the universe, reflected by people’s tendency to succumb to corruption.

Thus, it is indeed thoroughly appropriate to refer to the cinematographic genre/style Noir as such that derives out of the philosophy of Existentialism, which “places its emphasis on man’s contingency in a world where there are no transcendental values or moral absolutes, a world devoid of any meaning but the one man himself creates” (Porfirio 81). A typical Noir hero is an uprooted and cynical individual, who prefers to address life-challenges in a spontaneous but often socially irresponsible manner.

Such quality of Noir films predetermines their clearly defined tragic sounding. While trying to solve a crime or to tackle a particular ethically sensitive issue, a Noir protagonist usually ends up trapped in the web of lies surrounding it, which in turn corrupts the person to an extent when his act becomes virtually indistinguishable from that of his adversaries. As Borde and Chaumeton pointed out: “If police are featured (in film Noir), they are rotten – like the inspector in The Asphalt Jungle or the corrupt hard case portrayed by Lloyd Nolan in The Lady in the Lake – sometimes even murderers themselves… At a minimum, they let themselves get sucked into the criminal mechanism” (21).

The validity of this statement can be illustrated with respect to such classical Noir movies as the Big Sleep (1946), The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), Double Indemnity (1944), and Out of the Past (1947). After all, even though each of these films features its own unique plot, they nevertheless can be well discussed as such that promote the idea that one’s tendency to apply a rationale-driven approach to solving problems in life, maybe never guarantee to prove advantageous.

As a result, there is a strong aura of grotesque to these films, which is another discursive attribute of the cinematographic genre/style Noir, as a whole. Noir movies usually lack any central idea for the plot to revolve around – this is one of the reasons why in such films, the course of events remains utterly unpredictable until the very end. Therefore, there is nothing surprising about the movie-critics’ tendency to refer to the concerned genre/style as such that should be exempted from being subjected to positivist inquiry.

According to Spicer: “Any attempt at defining film Noir solely through its ‘essential’ formal components proves to be reductive and unsatisfactory because film noir, as the French critics asserted from the beginning, also involves a sensibility, a particular way of looking at the world” (24). It would prove quite impossible to disagree – to be understood; Noir films must be ‘sensed’ first.

Even though the theme of crime does define the course of events in just about every classical film Noir, there is no ‘classical’ Noir-plot to speak of. However, most plots in Noir films feature the prominent motif of a femme fatale (a woman uses her female charms to advance its own unsightly agenda – often at the expense of murdering her naïve lovers or driving them to the point of committing suicide). Moreover, these plots are often concerned with the main character realizing that he has been framed by his closest friends/colleagues, which in turn leads him to try to find his way out of the situation while paying very little attention to the applicable provisions of the law.

Initially, most classical Noir movies were considered belonging to the B-category (low-budgeted) of Hollywood films. The most notable examples of these films are Strangers on a Train (1951), Born to Kill (1947), and Raw Deal (1948). Nevertheless, as it was becoming increasingly clear to Hollywood directors that there was indeed a popular demand for ‘criminal melodramas’ (the term Noir was virtually unknown at the time), more and more Noir movies were being categorized belonging to the A-category (high-budgeted). Key Largo (1948) and The Asphalt Jungle (1950) represent the examples of high-budgeted Noir films.

The decline of Noir movies’ popularity through the late fifties is now assumed to have been brought about by the fact that by that time, Hollywood directors have fully aware of Noir, as a unique cinematographic genre. In its turn, the people’s newly acquired awareness began to undermine their ability to explore Noir themes and motifs outside of what became the established editing and thematic conventions of the concerning genre.

As a result, the plots and themes explored in many Noir movies through the late fifties have ceased being thoroughly original. As Naremore noted: “By the late 1950s… social criticism (in Noir movies) was smothered by banal plot conventions, and ‘incoherence’ became predictable” (19). Nevertheless, there appears to have been another factor that contributed towards the process of classical Noir films falling out of favor with moviegoers at the time – the fact that, throughout the mentioned historical period, the representatives of the ‘baby boomer’ generation began to define the qualitative subtleties of the socio-cultural discourse in the West.

Given the fact that these people’s foremost psychological traits have traditionally been considered their perceptual optimism and their belief in the progress’s linearity, it is fully explainable why they could not quite relate to the motifs of existential alienation and moral ambiguity, commonly explored in classical Noir films. Nevertheless, such films continue to be appreciated even today, as such that represents the value of a ‘thing in itself’ – all because by watching them, people can get a better understanding of the affiliated historical era.

The 1947 film Out of the Past (directed by Jacques Tourneur) represents one of the finest examples of what the Noir style is all about. The validity of this suggestion can be illustrated in regard to both: the film’s themes and motifs, on the one hand, and the specifics of the deployed editing-techniques, on the other.

Among the most notable indications that Tourneur’s film is indeed Noir can be deemed the fact that, even though the film’s main character Jeff Markham (private detective) does strive to act on behalf of truth and justice, he is shown being just as corrupted as the movie’s main antagonist Whit Sterling. To exemplify the full soundness of this suggestion, we can refer to the scene in which Whit admits to Jeff of having avoided paying taxes and complains about the fact that he may end up in jail because of it. Jeff responds by hinting that the situation could be handled with the mean of a bribe: “This may sound ridiculous, but you could pay them (governmental officials)” (00.42.52).

Clearly enough, Jeff is represented as a person fully aware of the actual ‘ways of the world,’ which in turn explains his strongly cynical attitudes, exhibited throughout the film’s entirety. For example, in one of the film’s scenes, Jeff expresses his willingness to mislead the police by suggesting to Whit that the death of Stefanos should be made to look like a guilt-ridden suicide (01.21.50). This, of course, establishes Jeff as a ‘morally flexible’ character – in full accordance with the generic conventions of Noir.

Another discursive reason for the film Out of the Past to be considered Noir is that in it, the motif of a femme fatale exerts a powerful influence on the plot’s developments. In Tourneur’s movie, this motif is embodied by the character of Kathie Moffat – a physically attractive and yet utterly wicked woman, who uses her good looks as a powerful asset, within the context of how she goes about scheming to gain access to money. After having met Jeff for the first time in Acapulco, she pretended to have fallen in love with him – all for the sake of turning this man against White, whom she robbed for $40.000.

Throughout the film’s entirety, Kathie never ceases to lie to Jeff about her real intentions, without even trying to sound convincing – all because she is aware of the fact that, while exposed to her looks, men lose their ability to think and act rationally. As Jeff admitted: “There was something about her (Kathie) that got me. A kind of magic or whatever it was” (00.35.55). Kathie’s moral depravity becomes especially apparent in the scene where, after having expressed her love to Jeff, she threatens to report him as the murderer of Eels, Stefanos and Sterling, in case he refuses to love her back: “You (Jeff) have nothing on me, but I’d make a fine witness for the prosecution” (01.30.05).

However, the clearest indication that the character of Kathie can indeed be discussed in terms of a femme fatale is the fact that Jeff’s ultimate demise appears to have been predetermined since the time of the earlier mentioned encounter between the two in Acapulco. As far as Kathie’s effect on Jeff is concerned, she did prove herself a ‘fatal woman’ in the full sense of this word. The same can be said about the effect of Kathie’s wickedness upon herself: “Frustrated and deviant, half predator, half prey, detached yet ensnared, she (a femme fatale) falls victim to her own traps” (Borde and Chaumeton 22).

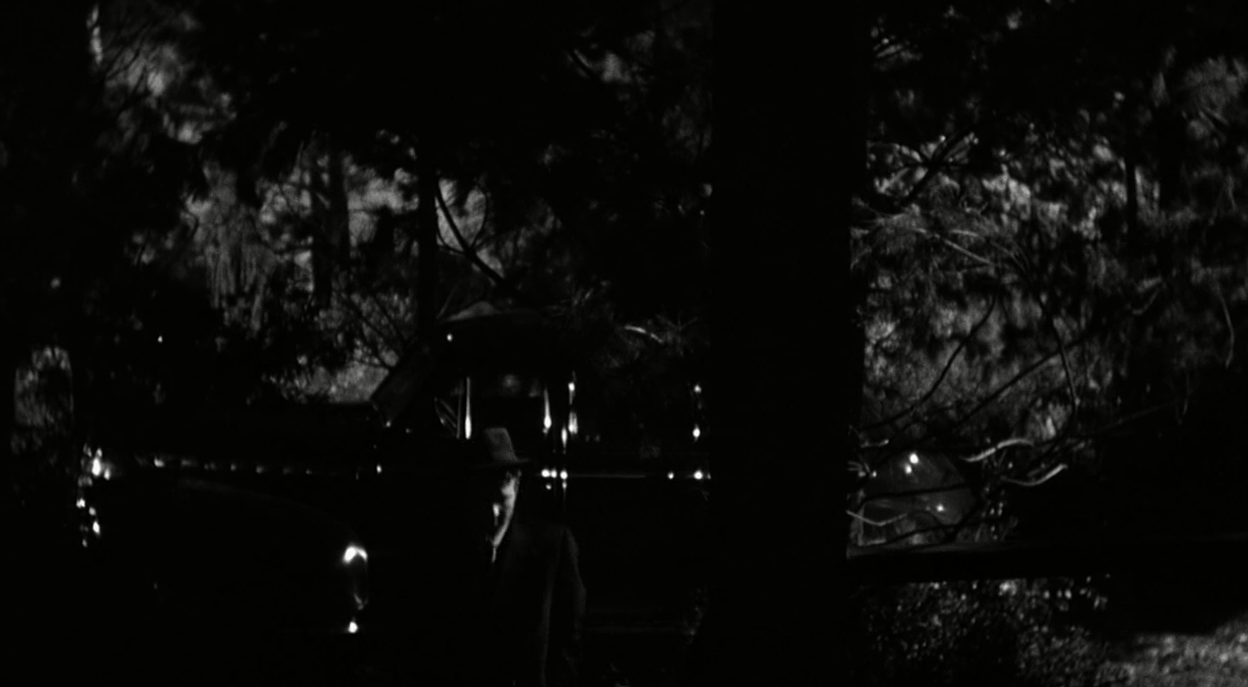

The film’s significance as such that belongs to the genre Noir can also be explored, with respect to the clearly expressionist editing-techniques, deployed by the director. One of these techniques had to with Tourneur’s strive to dramatize the interplay between light and darkness in a number of the film’s takes – something that was meant to increase the psychological intensity of the on-screen action. Probably the most notable take, in this respect, is the one in which Fisher (another private detective) is shown walking towards Kathie and Jeff, just before they enter the cabin in the woods. Even though the mentioned take lasts for a good ten seconds, viewers remain unaware as to the character’s actual identity, because, throughout the take’s entirety, his face remains obscured by shadow:

In this case, Fisher’s obscured appearance was meant to intensify the atmosphere of ominous suspense – hence, preparing a psychological ground for the audience members to remain emotionally attuned with the plot’s would-be subsequential developments. The same technique is being used in the film on a continuous basis, which partially explains why the bulk of the movie’s action takes place at night – this allowed the director to take full advantage of the associated mise-en-scenic opportunities, as well as to ensure the film’s overall ‘dark’ sounding.

The is even more to it – in Out of the Past, the mentioned interplay serves the purpose of prompting viewers to think of the protagonist as a morally ambiguous person, with ‘good’ and ‘evil’ being the integral parts of his existential identity – just as it happened to be the case with most people. This is the reason why Tourneur’s film is rich with the shots of Jeff’s half-lit face, such as seen on the screenshot below:

Apparently, while working on his film, the director never ceased to be aware of the fact that one’s perception of another person is unconsciously subliminal. Thus, it is not only that the film’s visual Noir-aesthetics establish a proper perceptual mood in viewers, but they also help the latter to gain a better understanding of the innermost causes behind the chosen approach to addressing life-challenges, on the part of the film’s main charters.

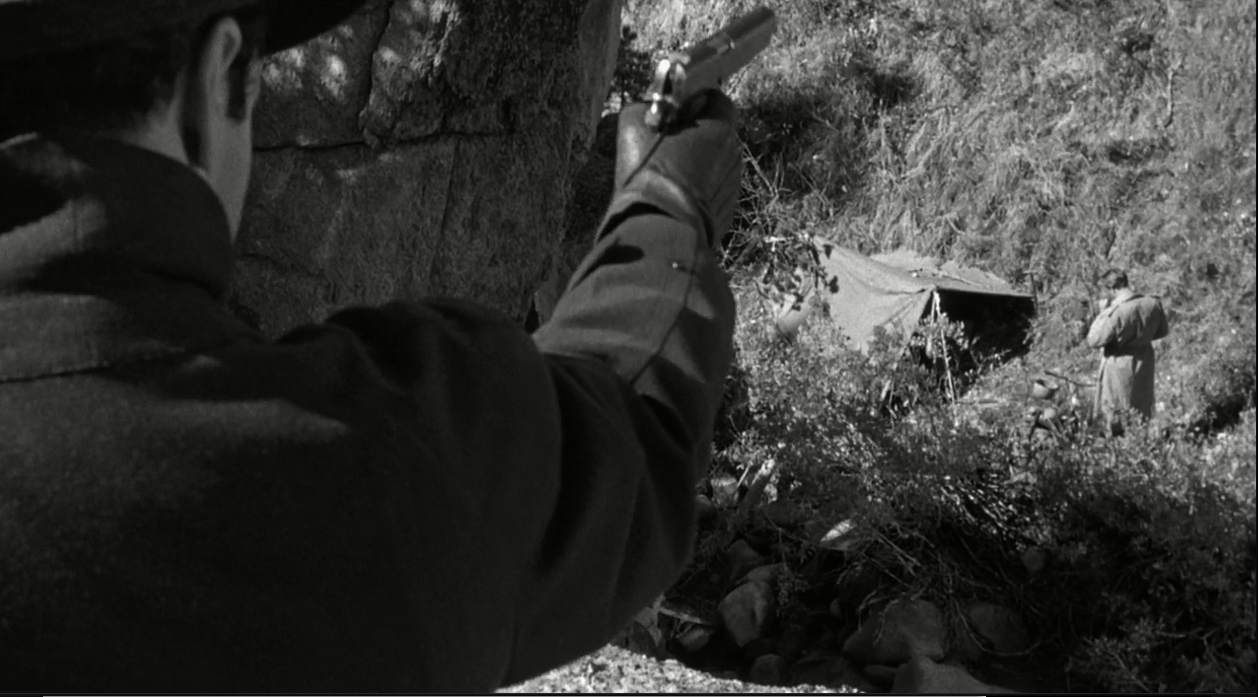

Another element of the ‘Noir-editing,’ which can be clearly seen in Tourneur’s movie, is exposing viewers to the sequence of two or more abruptly ended subsequiential shots that do not seem to make much dialectical (cause-effect) or compositional sense – something that is meant to emphasize the film’s absurdist overtones. We can refer to the following shots to illustrate the point:

Stefanos is aiming to kill Jeff.

The Kid is casting his fishing rod to ‘catch’ Stefanos.

Having been ‘caught’ and pulled down by the Kid, Stefanos falls off the cliff and dies.

The Kid tries to roll in dead Stefanos as if he was a fish.

It is understood, of course, that the mentioned sequence of shots did contribute rather substantially towards increasing the measure of the film’s discursive ambivalence, in the sense of encouraging viewers to perceive this particular plot-development as anything but logically sound (although thoroughly plausible). As a result, they come in close touch with their own unconscious fears, concerned with people’s deep-seated suspicion that there is no order/God in the universe and that there is nothing stable/predictable about the course of their lives. According to Borde and Chaumeton: “The anxiety in film noir possibly derives more from its strange plot twists than from its violence” (23).

There is, however, plenty of violence with the distinctive Noir-quality to it in Out of the Past, as well. The scene in which a fight breaks out between Jeff and Fisher (00.38.13 – 00.38.32) illustrates the legitimacy of this suggestion perfectly well. This scene’s foremost feature is that it commodifies violence as the most natural method of settling disputes between men. The rationale behind this suggestion is that:

- Both characters appear to be punching each other in a rather mechanistic (emotionally unengaged) manner as if they felt that there was nothing too extraordinary about trying to kill each other;

- Kathie enjoys being exposed to the spectacle.

Hence, yet another indication that Tourneur’s movie does belong to the genre Noir – the film’s most ‘graphic’ scenes, such as the one in which Jeff finds murdered Eels laying on the floor in his office, are concerned with the desacralization of death.

What has been said earlier leaves only a few doubts that Out of the Past does, in fact, belong to the cinematographic genre/style Noir. As such, it is likely to continue being referred to as the one of this genre’s best exemplifications.

Works Cited

Borde, Raymond and Etienne Chaumeton. “Towards a Definition of Film Noir.” Film Noir Reader. Eds. Alain Silver and James Ursini. New York: Limelight, 1996. 77-93. Print.

Conard, Mark. “Nietzsche and the Meaning and Definition of Noir.” The Philosophy of Film Noir. Ed. Mark Conard. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2006. 7-23. Print.

Naremore, James. “American Film Noir: The History of an Idea.” Film Quarterly 49.2 (1996): 12-28. Print.

Out of the Past. Dir. Jacques Tourneur. Perf. Robert Mitchum, Jane Greer, Kirk Douglas, and Rhonda Fleming, RKO Radio Pictures, 1947. Film.

Porfirio, Robert. “No Way Out: Existential Motifs in the Film Noir.” The Philosophy of Film Noir. Ed. Mark Conard. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2006. 77-95. Print.

Spicer, Andrew. Film Noir. Longman: Harlow, 2002. Print.