Introduction

A market or an industry is said to be competitive depending on the key market players, that is, suppliers and consumers. The number of suppliers seeking the demand of consumers in the market determines the competition in the market. The other factor that determines the competitiveness of a market is the barriers to entry and exit into the market in the long run.

The nature of competition in the market depends on the number of buyers and sellers in the market such that when both are many, the market assumes a perfect competition nature or monopoly if there is only one seller. The difference between the two extreme market structures is that industries operating in a purely competitive market have no power to set prices, and therefore, they operate at the prevailing price in the market.

On the other hand, a firm operating in a pure monopoly market enjoys full power to determine the price they charge in the market. A perfectly competitive market or perfect monopoly may be nonexistent in real-world markets, but they are very useful in gauging the level of competition in any given market.

The Meaning of Perfect Competition

According to Aumann (1996, 7), Perfect competition is a market structure that assumes the optimum allocation of resources. The market is theoretical and nonexistent in real life. A perfectly competitive market is defined as a market structure in which there are many buyers and sellers such that no one has the power to set or control market prices.

Firms operating in a competitive market are price takers as they operate on the price that is prevailing in the market. There is no competition concerning price. The competition is determined by the quality of the products sold by a particular seller and the preferences of the buyers.

Characteristic of Perfect Competition

A market is considered to have perfect competition if it is characterized by a number of factors. Firstly, all parties in the market have perfect knowledge of the products offered in the market and the prices attached to them. Secondly, there are many buyers and sellers in the market, and therefore no one is obligated to set the prices, but all take the prevailing price (CliffsNotes, 2010, p. 1). Market entry is also free such that firms could join or leave the market any time they decide, depending on the prevailing condition.

The suppliers can sell as much as they can in the market but only at the market price. They have no authority to make prices. There is also a homogeneity of products that are produced by the firms (Aumann, 1996, 7). There is no advertisement in the market because all parties are price takers, and products are perfect substitutes. The perfect knowledge of prices and products also makes advertisement unnecessary.

Normal and Supernormal Profits in Perfect Competition

Normal profits in perfect competition are earned when a firm reaches an economic equilibrium where average cost equals marginal revenue at the point where the firm maximizes profit (Stigler, 1987, 539). Marginal revenue, price, average cost, and marginal cost are always the same when the firms are at their optimum level of production. Normal profit is the profit that is just enough to enable the firm to continue producing and stay in business because it can cover its costs.

In case the average cost falls below the price, the firm earns a supernormal profit. This happens at a profit-maximizing output but does not occur in the long run. Any amount of profit that exceeds the normal profits is categorized under supernormal profits and is earned in the short run.

Short and Long Run Perfect Competitor Price/Output Diagrams

Short Run

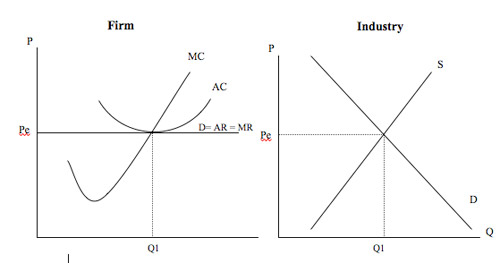

In the short run, there may be high demand for commodities in the market. This causes the increase in the price of the commodities above the average cost making the firm earn supernormal profits. This attracts many firms into the industry/market. This shifts the supply level in the market higher, causing the price to go down (Aumann, 1996, 7).

The profit earned by the new and the existing firms reduces, thus completing away the supernormal profits. The firm can also earn supernormal loss in the short run if the average cost increases above the price. The situation will be corrected when new firms will leave the market, causing supply to go down.

Long Run

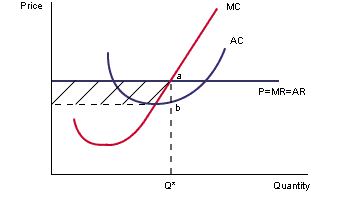

Based on the diagrams above, we see that it is possible for a firm to earn normal and supernormal profits. In the first diagram, the average cost is below the price, meaning that the firm can make a supernormal profit that is equivalent to the shaded region. This can be represented by Q* (a – b).

The firm is also earning a normal profit at the point where P=MR=MC. This is the equilibrium level of the firm where normal profits are experienced at the point where marginal cost = marginal revenue at the minimum point of the average cost, as shown in the second diagram.

Perfect Competition and Public Interest

The perfect competition will have a great impact on public interest in some respects. For example, consumers may end up getting poor-quality products or services at high prices.

There is also a lack of product variety, showing that consumers have low sovereignty in choosing what best suits them. This is due to the lack of product differentiation. Poor quality is contributed by the fact that there is no competition concerning commodity design and specification because the price in the market is the same.

Allocative and Productive Efficiency

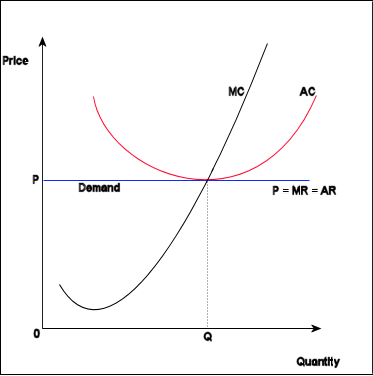

A firm is said to be efficient if it attains the optimum production level and also the optimum distribution of scarce resources (CliffsNotes, 2010, p. 1). Allocative efficiency in perfect competition occurs when the firm distributes goods and services according to the consumers’ preferences. It occurs at the point where P=MC, that is, price equals marginal cost.

Productive efficiency, on the other hand, occurs when a given amount of inputs produces a maximum volume of commodities. In this case, the output is achieved at minimum average cost and can occur in the long or short run. In this diagram, both allocative and productive efficiency is achieved at the point (Q, P), where P=MC=AC. At this point, AV (average cost is at its minimum) means that productive efficiency is achieved. Allocative efficiency is also achieved at the same point because of P=MC (price = marginal cost)

Conclusion

Perfect competition as a market structure does not exist in a real market situation. However, its characteristics are very useful in measuring the nature of competition in other market structures like an oligopoly, monopsony, et cetera.

Reference List

Aumann, R. J., 1996. Existence of Competitive Equilibrium in Markets with a Continuum of Traders. Econometrical, V. 34, N. 1 (1966): pp. 1-17.

CliffsNotes. 2010. CliffsNotes.com. Conditions for Perfect Competition. USA: Wiley Publishing, Inc. Web.

Stigler, J. G., 1987. Competition, The New Palgrave: a Dictionary of Economics, First edition, vol. 3, pp. 531–46.