Global warming, animal extinction, and the depletion of natural resources are among the many indications that the Earth’s natural ecosystem is at risk. The consequences of such environmental issues range from health problems to the planet’s viability. The drive to ‘go green’ is evident in our daily lives, from the food bought to the products used at home. The present concerns are exacerbated by human behavior. Oceanic plastic pollution is a global crisis affecting both humans and marine species alike. As a consequence of modern industrialization, an increasing amount of plastic waste is continuously finding its way into the oceans. It is reported that approximately 40% of plastic is found on the oceanic surface (Centers for Biodiversity, 2018). This has been instigated and maintained by the rising demand for plastics due to their flexibility, versatility, and relatively inexpensive cost.

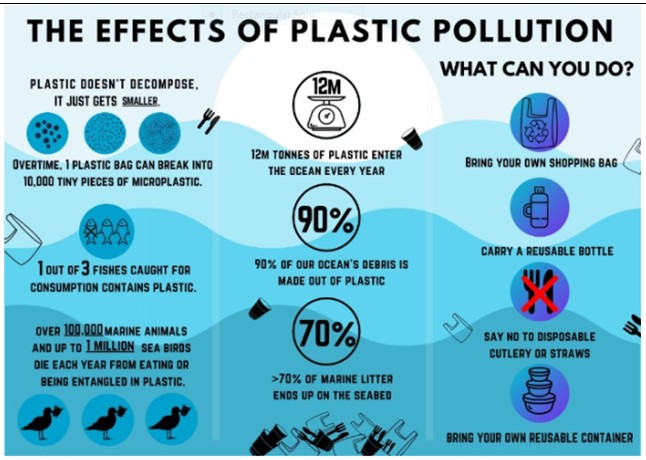

Over the past few years, several technical solutions have been formulated to curb the issue of plastic pollution. However, they have proven to be ineffective, and this has emphasized the need to highlight the impact of human behavior (Heidbreder, Bablok, Drews, & Menzel, 2019). Literature suggests that there is a gap between plastic-related behavior and high problem awareness (Heidbreder et al., 2019). There are several factors that may explain people’s lack of change. For instance, most environmental crises occur gradually, in that, they take centuries to develop; hence, this inhibits their ability to see the direct consequences of human behavior. Several psychological intervention strategies can be used to combat such kinds of acts, with one channel being the media. Posters, a type of print media, play a significant role in spreading information about reducing plastic usage and raising awareness. Posters placed and distributed in public spaces and prepared with strong visualization served as efficient tools in influencing and changing public behavior and opinion on an issue.

Research has shown that the media is significantly impactful in educating the public and influencing their opinion and conduct. The intensity of their impact is heightened when their visualization and message embrace emotion and rationality, which are regarded as foundational components of human life. Although similar in terms of their basis, there is an unclear disparity between these two elements with regard to advertising (Oñate, Teixidó, & Cagiao, 2018). Regardless, when distinguishing the communication models in the rational discourse, the two typologies can be differentiated. The rational model is divided into an informative and persuasive one (Oñate et al., 2018). The former is the classic version in which preference is given to a specific product, but there are also rational approaches seeking consumer simplicity. Conversely, the latter utilizes emotional arguments to connect with the target audience and make a product more attractive. On the other hand, the emotion model is also subdivided into different communication models (Oñate et al., 2018). The classic emotional model retorts to the description of emotional communication, in which other archetypes, such as the social creativity model, should be incorporated. Conversely, in the Fame model, the advertising principle is based on instigating and fostering popularity.

Aim of the Study and Hypotheses

With regards to the previous reasoning, the primary objective of this study is to compare the effectiveness of posters in countering plastic pollution. Moreover, although psychological interventions are effective, they are understudied (Heidbreder et al., 2019). In relation to visualization, further research aimed to determine which type of themes, rational and emotional, maximized its effectiveness. Therefore, the following hypotheses were developed pertaining to the aim of the study:

- H1 – The environmental concern measure and green scale of the posters will be higher than that of the questionnaires without any intervention.

- H2 – The environmental concern measure and green scale of the emotional poster will be higher than the rational one.

Methods

Experimental Design and Procedure

The study embraced a quasi-experimental field design that comprised of three conditions. It primarily emphasized the comparison of the effects of rational and emotional posters. The participants subjected to the three conditions constituted 96 college students; with 48 respondents (50%) having a psychology background for the control condition, and the other half, 50%, having no psychology background. Participants were recruited, and questionnaires were administered on the same day. Two types of questionnaires were administered. First, the baseline (survey with no treatment, which acted as the control), followed by questionnaires embedded with rational and emotional posters that constituted the experimental condition.

Questionnaire

Questionnaires were used to evaluate the perception of posters and their psychological impacts. One only contained questions, the other contained questions regarding a poster with an emotional theme, and the third, questions regarding a poster (Poster A) with a rational theme (Poster B). The contents of the questionnaires fell under two topics; the environmental concern measure and the green scale. The 96 respondents were randomly approached and handed out the questionnaires immediately after obtaining consent. Almost everyone can produce posters; hence, they are a relatively cheap method of spreading information. The first items of the survey focused on the gender and age of the participants. After that, the participants reviewed the two posters, and the questions on these two images were asked. These items revolved around their perception of plastic pollution, their littering behavior, and possible mitigation strategies. The answers were graded on point rating scales from 1, suggesting ‘not at all’ or ‘strongly disagree.’

Statistical Analysis and Manipulation Check

SPSS statistics version 20 was used to analyze the data collected. The three data collection tools were contrasted based on their total environmental concern measure (ECM) and total green scale (GS). The inferential statistical methods used comprised the Shapiro-Wilk’s, the Freidman’s, and Post Hoc tests. The criterion for the main hypotheses on the difference between the emotional and rational posters was that they hold specific characteristics. Consequentially, the below manipulation check hypotheses were formulated:

- Manipulation check 1: The baseline survey will have lower ECM and GS scores than the posters.

- Manipulation check 2: Poster A will have higher ECM and GS scores than B.

Results

In terms of gender, 68 (70.8%) of the participants were female and 28 (29.2%) male.

In determining, the relationship between and within groups, the Shapiro-Wilk’s test was first used to test for normality since the sample size was relatively small. In table 1, for all conditions except GS1, the p-value was less than 0.05, therefore, indicating a significant result. In simpler terms, this meant that the data was not normally distributed, and only the GS1 was an exception.

Subsequently, due to the lack of normality, Friedman’s test was used to test for the difference between groups. The results demonstrated that there was a statistically significant difference between the baseline questionnaires and those embedded with rational and emotional posters, χ2 (5) = 395.739, p = 0.000.

Comparison between the Baseline and Experimental Conditions

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that the questionnaire with the rational poster did not elicit a statistically significant change in the environmental concern measure (ECM) as compared to the baseline questionnaire (Z= -1.531, p <.126). On the other hand, the test also illustrated that the questionnaire with the emotional poster elicited an ECM that was statistically significant and higher than the baseline version (Z= – 2.998, p <.003). With regards to the green scale (GS), the Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that the questionnaire with the rational poster elicited a statistically significant change in GS and was comparatively higher than the baseline version (Z = -4.703, p <.000). Conversely, it demonstrated that there was a statistically significant difference between the GS of the questionnaire with the emotional poster and the baseline option and that the former was higher (Z = -5.401, p <.000).

Comparison between the Rational and Emotional Posters

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test illustrated that the questionnaire with the emotional poster elicited an ECM that was statistically significant and higher than the questionnaire with the rational poster (Z= – 2.071, p <.038). On the other hand, the test showed that the questionnaire with the emotional poster elicited a statistically significant change in GS, which was comparatively higher than that with the rational poster (Z = -4.406, p. <.000).

Discussion

Overall, the results suggest that posters regarding environmental sustainability are suitable for raising awareness on the issue of plastic usage and pollution, as they might lead to positive changes in conduct. However, because actual plastic usage and disposal conduct was not factored in this research, making definite conclusions would be considered premature. This should be assessed by additional studies examining the behavior aspect associated with environmental concern and green scale measures in relation to the use of posters to counteract plastic usage and littering.

H1 – The environmental concern measure and green scale of the posters will be higher than that of the questionnaires without any intervention

The first hypothesis was supported. Posters had a positive effect on the perception of participants towards reducing plastic usage. The presence of the control group, which was the baseline questionnaire, facilitated the establishment of clarity, specifically on the degree of impact that posters have on the tendency for improved behavioral interventions as compared to past plastic usage behavior. Posters have been often utilized in campaigns to counteract littering, and in most cases, their success has been shown in previous studies (Hedibreder et al., 2019; Hansmann & Steimer, 2016). Taking this into consideration, this study is coherent with previous findings, which found that environmentally-oriented print media were effective. In Hansmann and Steimer (2015), environment-oriented, humorous, and authoritarian posters were used to advocate against littering, and their behavioral effectiveness was evaluated. The results indicated that the environment-oriented and humorous posters were more effective than the authoritarian ones.

H2 – The environmental concern measure and green scale of the emotional poster will be higher than the rational one

The study findings supported the second hypothesis. Furthermore, with respect to the two poster aspects, the emotional posters were illustrated to be significantly more impactful than the rational ones. This suggests that the print media, with emphasis on emotional posters, can effectively complement environmental campaigns. According to Hedibreder et al. (2019), norms, habits, and situational factors were found to be predictive of plastic consumption and disposal behavior. Therefore, emotional-behavioral interventions seem to invoke more significant behavioral changes as compared to rational ones.

This study has several limitations. For instance, in the present study design, the improvement of conduct in comparison to past plastic usage behavior could not be evaluated separately for the three different questionnaires. This is because the research tools constituting the interventions were presented simultaneously to all respondents. As a result, future research should consider the long-term effects of posters on plastic usage and littering. It should also compare the impact of emotional and rational posters between participants with a psychology background and those without.

Conclusion

In summation, this study suggests that the use of posters is a promising way of counteracting plastic usage and littering. Concerning posters, the results indicate that emotional posters focusing on the hazards of plastic pollution are more effective than rational ones. Nevertheless, additional research examining the actual behavior observed in conditions with the two posters is needed to complement this present study. Therefore, it is commended that posters containing emotional and rational messages be used in campaigns against littering to gain from complementary effects.

References

Centers for Biological Diversity. (2018). Ocean plastics pollution.

Hansmann, R., & Steimer, N. (2015). Linking an integrative behavior model to elements of environmental campaigns: An analysis of face-to-face communications and posters against littering. Sustainability, 7(6), pp. 6937-6956.

Hansmann, R., & Steimer, N. (2016). A field experiment on behavioral effects of humorous, environmentally oriented authoritarian posters against littering. Journal of Environmental Research, Engineering and Management, 72(1), pp. 35-44.

Heidbreder, L. M., Bablok, I., Drews. S., & Menzel, C. (2019). Tackling the plastic problem: A review on perceptions, behaviors, and interventions. Science of the Total Environment, 68, pp. 1077-10.93.

Oñate, C. G., Teixidó, E. F., & Cagiao, P. V. (2018). Rational vs emotional communication models. Definition parameters of advertising discourses. IROCAMM, 1(1), pp. 88-104.