Introduction

The increased media coverage of the dismal working conditions exhibited in the Kawah Ijen Volcano mines and escalating demand for sulfur in contemporary industries has led to a heightened public awareness of the sulfur supply chain. There are two primary methods of extracting sulfur, including the extraction from subterranean molten sulfur deposits and surface sulfur pits and sediments, and the recovery of sulfur as a nondiscretionary by-product of petroleum and natural gas refinement (Alkasem et al., 2017). The increased pressure outlines an essential opportunity for the International Labor Organization (ILO) to present the lived-in conditions and work hazards of mine workers to mining companies and stakeholders, including the Indonesian government, for better regulation and occupational protection.

The primary sulfur mine in Indonesia is known as Banyuwangi, which is located within the Ijen Mountain Crater in Tamansari Village, Licin District. Sulfur mining has been ongoing in the Kawah Ijen crater since 1968 and is an essential economic resource for the region and the country as a whole. The applications of sulfur are vast, as the mineral mined here in the Kawah Ijen crater is processed and used in the manufacture of countless essential products including rubber, matches, insecticides, bactericides, fertilizers, cosmetics, batteries, medication, sugar, and film. However, the mining process itself is overwhelmingly dangerous and traditional. This is a significant concern for the ILO, and broad labor policy recommendations are necessary for the sustainability of mining processes in the Kawah Ijen region.

This report has been commissioned by the ILO, a constituent body of the United Nations, and primarily aims to expound on the working conditions and related occupational hazards facing miners in the Kawah Ijen Volcano mines in East Java, Indonesia. The research project was handled by an independent research firm and involved the extensive assessment of the work hazards encountered by miners in the Banyuwangi mine in the Kawah Ijen sulfur-mining region and the consequent health impact in the short and long run. Viable recommendations to ILO have also been made based on the findings of the review.

The study will focus on the harmful labor conditions surrounding sulfur miners at Kawah Ijen, who mine and ferry sulfur chunks out of the Banyuwangi crater mine. It identifies the occupational hazards of working in the Kawah Ijen Volcano mine, along with the social and environmental impact of mining activities. Finally, the economic sustainability of the practice is reviewed and viable policy recommendations are made based on the reviewed information. Prevalent research also suggests significant cause for concern in the long-term health effects of exposure to sulfuric gases for miners and surrounding living settlements. Despite the latter being outside the scope of this report, this research body would recommend that the ILO and other affiliated bodies commission further investigation.

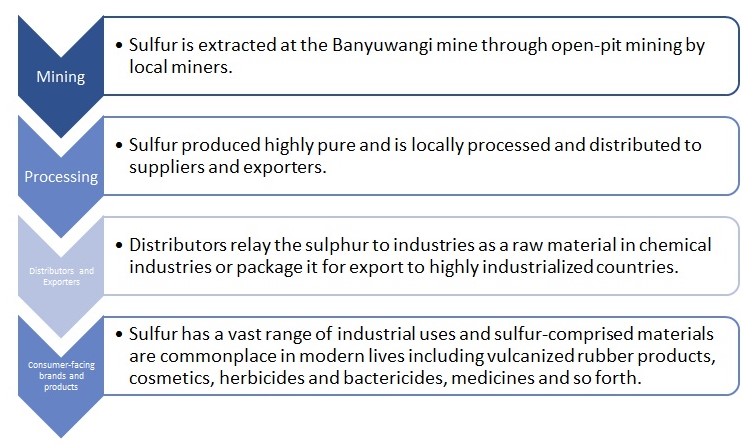

Outline of Sulfur Supply Chain

A local sulfur refinery pays the Kawah Ijen miners based on the weight of sulfur availed. The elemental sulfur mined is relatively pure, averaging about 99.5% purity, with contamination being small organic matter trapped (Hardy, 2020). Consequently, much of the sulfur is packaged and sold to suppliers, distributors, and exporters. The sulfur is then sold to chemical companies, or exported to industrialized countries where the demand for sulfur is high. Sulfur is primarily used in the manufacture of Sulfur dioxide (SO2) for the development process of Sulfuric acid, which has a wide range of consumer-facing commercial applications.

This report’s primary focus is on the mining aspect of sulfur production in the Kawah Ijen region of East Java Indonesia. The following research questions will be considered in the review:

- What are the occupational and health hazards experienced by miners in the Kawah Ijen Volcano mine?

- What is the social and environmental impact of the mining activity in Kawah Ijen?

- Is the mining endeavor at Kawah Ijen economically sustainable?

Methodology

There is extensive media coverage of the labor conditions and work hazards borne by sulfur miners in the Kawah Ijen region of Indonesia. As a result, this report utilizes a qualitative approach to accurately document and review the working conditions burdening Indonesian miners, including the occupational health and safety of individuals mining the Banyuwangi mine, the social impact of mining activities and the environmental repercussions of the endeavor, and finally the economic sustainability of mining operations as they exist in the Kawah Ijen sulfur mining operation.

Labor Issues and Mining Practices in Sulfur Production

Occupational Health and Safety

Sulfur mining at Banyuwangi occurs when local miners tap the volcano’s reserves of sulfurous gases with naturally-occurring fumaroles or artificially-inserted ceramic pipes. Within these pipes, the sulfurous gases cool and condense to molten states and drip out along the Ijen crater lake’s edge, solidifying into pure and minable sulfur. Almost 300 miners proceed into the Ijen mine daily, breaking up the sulfur with metal pipes, and packing them into simple traditional baskets made of bamboo and locally named “Pikula” (Setiadji and Artaria, 2017). The miners then haul the loaded plans weighing on average 70 to 90 kilograms to a weighing station.

Miners on average make the trip to the weighing station twice a day. This journey comprises a 300-meter climb from the bottom of the crater to the rim, at a gradient of 45 to 60 degrees, and a distance of 3 kilometers from the summit to the weighing station. These miners approximately 20% of the daily continuous sediment of sulfur (Hardy, 2020). The typical daily earning of a miner working the Banyuwangi mine is USD 13 (Watson and Boykoff, 2016). Despite the wages being considered by the local mining population as fair, considering the cost of living in the area, miners expose themselves to arduous working conditions; compromising their health in the process.

The now-antiquated sulfur mining process in the Indonesian Kawah Ijen area poses explicit health hazards and high work hazards for the miners. According to a BBC report, 74 miners had died over four decades from incidents directly attributable to their place of work within the sulfur mines (Collins, 2017). A majority of these deaths are due to toxic fumes from fumaroles in the active volcano. The constant and noxious fumes comprise concentrated levels of hydrogen sulfide and sulfur dioxide, which irritate a miner’s eyes, corrode the lungs, and even have the potential to dissolve teeth (Tox Town, no date). Many miners wear little to no protective gear, and cannot afford masks, gloves, or chemical suits (Hardy, 2020). As a result, most of the protective wear worn by miners in the Banyuwangi mines comprises scarves and rags.

Kawah Ijen is a dangerous location. The altitude is relatively high, and the crater’s sides are slippery, steep, and jagged, which increases the likelihood of accidents by falling. The active volcano also can erupt unexpectedly, leading to catastrophic consequences. The crater lake has high levels of sulfur dioxide bubbling through it consistently (Khan, 2017). As a result, the Ijen Lake is highly acidic and is considered to be the most acidic lake in the world with a pH comparable to a car battery acid (NASA, 2017; Caudron et al., 2017). These elements collectively make the Kawah Ijen area an extremely hostile and dangerous work environment.

Finally, miners at the Banyuwangi mines constantly haul heavy loads up treacherous terrains leading to gruesome external and internal injuries. Miners will often have heavily scarred backs, along with deformed spines and bent legs. Most sulfur miners also take very little time to rest and recuperate from the continuous crushing physical effort of hauling heavy sulfur loads from the mines to the weighing stations. Miners exposed to sulfur over prolonged periods have a dismally low life expectancy of 30 years of age (Xinhua, 2019). The physical effort required by miners within the Kawah Ijen mine is extremely exhaustive and unique to the region. However, it is harmful to human health and manifests in extremely short life expectancies among miners.

The mining endeavor in Kawah Ijen is unique, but this has not always been the case. There are several volcanoes with sulfur-rich deposits in various countries in the world, including Chile, Italy, and New Zealand. However, traditional miners in these other locations ceased antiquated mining methods in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. (Dickerman, Trenchard and d’Unienville, 2018). Contemporary sulfur mining operations are almost entirely mechanized. However, the Javanese Miners working in the Kawah Ijen mines are highly against the mechanization of mining in the region, citing a preference to brave the hazards of the mine and volcano, than risk losing their livelihood (Hardy, 2020). It is, therefore, paramount for stakeholders in the Indonesian Mining industry, including the government to devise viable changes in policy that would maintain the integrity of the labor-intensive mining operation while reducing the hazards associated with the mining endeavor.

Social and Environmental Impact

The mining operation in Kawah Ijen remains relatively unchanged from ancient times. As such, the passage of time and development of new mining processes has barely affected the mining operations. The communities living around the Kawah Ijen hand down their proficiencies in apprenticeship to latter generations, effectively passing down their mining duties to the younger men, who will do the same to generations to come. As a result, the Kawah Ijen mining operation has become integral to the social structure and functioning of neighboring communities.

Furthermore, the wages from the mine are considered fairly lucrative, given the contrasting cost of living in the region. As a result, many individuals will choose to work the mines, and heavily oppose any interventions designed to mechanize the mining process as this would effectively put their livelihoods at risk. Many of the miners prefer to work at night, where the heat of the volcano is not compounded by the heat of the sun (Dukehart, 2015). Therefore, the communities working at the Kawah Ijen mine have an all-day social footprint, with workers getting to and from the mine at all hours of day and night.

From an environmental perspective, the mining operation at Kawah Ijen has a relatively low impact. The extraction of the mineral is done through primarily natural means, and unobtrusive artificial, hand-held, traditional implements. Consequently, the mining operation itself introduces little to no adverse effects on the environment. Furthermore, the majority of the communities working in the Kawah Ijen mine are heavily reliant on nature as traditional herbal concoctions are primarily used to prevent and treat illnesses. Herbal medicine is used as it is considered by sulfur miners to be most useful, and practical considering the distances that miners have to cover to seek more conventional medicine (Setiadji and Artaria, 2017). This reinforces the miners’ use of herbal medicine and in extension, their appreciation of nature.

Economic Sustainability

The Kawah Ijen volcano mine, located on the Java Island of Indonesia has been in operation since 1968. It employs approximately 300 miners paid on average of USD 5 to 7 dollars a trip or a total sum average of 13 US dollars a day. The miners also extract approximately 14 tons of sulfur a day, which constitutes roughly 20% of the continuous daily deposit. The sulfur ultimately is used in local chemical plants, but the majority is exported to industrialized countries, primarily China and Southeast Asia (Dukeheart, 2015). Arguably, the efficiency of the mine, along with the daily yield could be considerably increased with the introduction of modern and mechanized mining techniques. However, local communities and miners are heavily reliant on the mine for their source of livelihood and are, understandably, against mechanization. This is speculated as the main reason behind the persistence of the labor-intensive mining techniques but in the face of arduous work conditions, better policies ought to be implemented to protect the miners.

Policy Recommendations

Government Intervention and Regulation

The sulfur-mining industry, for instance, has a high level of autonomy, with private mining companies holding a lot of power in the field. This situation has been exacerbated by several newer laws, which have been widely viewed as aimed to give mining entities more power within the industries and far lesser obligations (Jong, 2020; Library of Congress, 2020). This sets a dangerous precedence and allows the unbridled exploitation of labor-intensive sites such as Kawah Ijen and other national resources such as forest lands and ecological reserves.

The ILO currently lobbies for workplace reforms and related occupational improvement programs all over the world. It would be prudent for the Indonesian government to revise some of the existing laws in the mining industry, which would ideally set minimum wage requirements for many mining companies, whereby sulfur miners in the Kawah Ijen region can get sufficient pay for their daily sustenance as well as investing in safety gear. The ILO, through the support of local worker groups and labor organizations, can help in the drafting of viable Labor Bills, and institute legislative reforms.

Furthermore, the ILO can lobby for the Indonesian government can regulate mining activities by introducing complementary health and safety procedures, whereby miners would be legally obligated to wear sufficient protection before venturing into the mines. This would give increased protection to miners, and ideally reduce long-term health complications stemming from extended exposure to sulfurous gases.

Robust Health and Safety Infrastructure

In the event of an accident, or the arising of complications stemming from sulfur exposure, within the Kawah Ijen mines, most of the miners highly prefer resulting to herbal interventions due to their perceived practicality and effectiveness. This situation is exacerbated by the fact that access to conventional medical procedures is severely limited due to distance. This committee would recommend lobbying for the intervention of stakeholders in the health sector, including the Indonesian government to develop mobile clinics and a community healthcare center for easier and scalable access to modern healthcare delivery.

Furthermore, better educational interventions would be warranted to sensitize miners on the adverse effects of prolonged sulfur exposure. Being an affiliate of the World Health Organization under the UN umbrella body, the ILO can requisition the deployment of remote health workers and training of first-aid personnel and mass-education strategies on issues relating to health and occupational safety. This would, ideally, help the adoption of safer mining procedures, including wearing safety and protective gear. Furthermore, a better understanding of physiological stress within the human body among miners may improve the uptake of sufficient rest and recuperation, which would reduce the cumulative stress and adverse effects of miners’ bodies exhibited.

These interventions can be implemented through relatively inexpensive community outreach programs and the implementation of community health volunteers who would be embedded with miners and the entire community at large to pass a healthier working agenda. The lobbying for safer working conditions for Kawah Ijen miners is also in line with the ILO’s primary goal which is the improvement of working conditions worldwide, and the provision of decent work for populations all over the world. Consequently, advocacy for health-conscious and overall safer mining practices in the labor-intensive Banyuwangi mines would significantly help alleviate the dangers associated with the occupation.

Reference List

Alkasem, A. et al. (2017) ‘Corrosion control in sulphur recovery units–claus process’, Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference, pp.13-16.

Caudron, C. et al. (2017) ‘New insights into the Kawah Ijen hydrothermal system from geophysical data’, Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 437(1), pp.57-72.

Collins, T. (2017) ‘Journey into hell: striking images reveal how sulphur miners in Indonesia risk their lives to brave toxic fumes from an active volcano for just £3 a day’, Daily Mail, Web.

Dickerman, K., Trenchard, T. and d’Unienville, A. (2018) ‘Stunning photos of treacherous sulfur mining on an active volcano’, The Washington Post.

Dukehart, C. (2015) ‘The Struggle and Strain of Mining “Devil’s Gold”’, National Geographic.

Hardy, M. (2020) ‘Meet the sulfur miners risking their lives inside a volcano’, Wired, Web.

Henriques, M. (2019) ‘The men who mine the ‘Devil’s gold’, BBC.

Jong, H. (2020) ‘With new law, Indonesia gives miners more power and fewer obligations’, Mongabay Environmental News.

Khan, G. (2017) ‘Striking photos of the men who work in an active volcano’, National Geographic, Web.

Library of Congress (2020) Indonesia: revision of mining regulation. Web.

Mantiri, F. and Lee, P.T. (2017) ‘Working capital and profitability performance: an evidence from Indonesia mining companies listed in Indonesia Stock Exchange’, Abstract Proceedings International Scholars Conference, 5(1), pp. 91-97.

NASA (2017) Ijen Volcano, Indonesia.

Setiadji, W. and Artaria, M.D. (2017) ‘The traditional way in preventing and overcoming health problems among sulfur miners in the craters of Ijen’, 1st International Conference Postgraduate School Universitas Airlangga:” Implementation of Climate Change Agreement to Meet Sustainable Development Goals” (ICPSUAS 2017) conference proceedings. Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia. Atlantis Press, pp. 333-359

Tox Town (2020) Sulfur dioxide. Web.

Watson, I. and Boykoff, P. (2016) ‘Volcano mining: the toughest job in the world?’, CNN, Web.

Xinhua (2019) ‘Miners work at traditional sulfur mines in Banyuwangi, Indonesia’, Xinhuanet, Web.