Introduction

Juvenile recidivism is a major concern in the United States Justice system. Powell et al. (2019) define juvenile recidivism as the tendency of a minor to repeat an offence or antisocial behavior after going through the juvenile justice system. For a long time, the Department of Justice has been keen on finding ways of reforming juvenile offenders in a way that does not expose them to threats in normal prisons. When laws were enacted to facilitate arrest, prosecution, and incarceration of juvenile offenders, the goal was to ensure that they are offered the best opportunity to reform into responsible citizens (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2017). The spirit of the law was to create an environment where such minors do not interact with hardened criminals who might have negative impact on their future.

The problem that stakeholders in the criminal justice system face is that minors who have been incarcerated are more likely to commit the crime than their colleagues who received non-custodial sentence. Mathys (2017) explains that adolescents who have gone through the prison sentence tend to be more aggressive and are likely to commit more serious offences than what they did before going to jail. The trend is creating a concern because it shows a pattern where the system is failing to reform these children. Instead of transforming them into better citizens, it enables them to gain dangerous skills and develop a network of serious criminals who would then help them commit more serious offences (Kurlychek & Gagnon, 2020). Reentry program, where a child has to be re-admitted into correctional facility because of repeat offence, is becoming common, which is a worrying trend. The purpose of this paper is to investigate risk factors associated with juvenile recidivism and to develop prevention programs that can help in combatting the problem.

Risk Factors Associated with Juvenile Recidivism

Juvenile justice system in the United States was created when it became apparent that the number of minors being subjected to the justice system meant for adults was on the rise. The intension was to ensure that the alternative justice system would create a platform that would help reform the juveniles who are engaged in criminal acts. However, studies have shown that juvenile recidivism is on the rise in the country, which means that the strategy is not working as per the expectations. According to Powell et al. (2019), this phenomenon has attracted the attention of many scholars around the world because the problem is not unique to the United States. It has been necessary to explain why the system developed to specifically help child offenders is turning out to be the platform where they learn new and dangerous skills that transform them into hardened criminals. Various factors were identified in this study that can help explain factors which are likely to make children repeat offenders even after going through the reform program.

Family and Environment

The environment in which a child lives, including the family setting, has a massive influence in who they become and people they associate with both in and out of school. Some neighborhoods have been found to be toxic and dangerous for the normal development of children. Others have been classified as being safe and ideal for minors (Walker & Bishop, 2016). The researcher identified family setting, antisocial peers, gang involvement, and peer rejection as some of the risk factors associated with juvenile recidivism.

Family

The family is the first and primary learning environment for children as they grow up. Wolff and Balglivio (2017) explain that as a child grows, most of them look upon their parents as their role models. A young boy would want to be like the father when they grow up and a young girl will look up to the mother. The problem starts when a child grows in dysfunctional families (Vidal et al., 2017). When the father is a drunkard, the child grows up knowing that it is normal to use alcohol because that is what they see. When parents are engaged in constant verbal and physical fights, they learn that such actions are the best ways of dealing with conflicts.

Adverse parenting practices is another problem that has been associated with juvenile recidivism in the country. According to Ryan et al. (2013), some parents fail to understand their role in the lives of their children. As such, they allow them to do what they want without any consequences. They grow up knowing that their actions will not be questioned or subjected to punishment if they are wrong. Wolff et al. (2018) note that neglect is another area of poor parenting in the country. When the child is not given the attention they need, they may resort to becoming associated with criminal gangs. Abuse by parents, guardians, or family friends is another problem that has always been associated with this problem. Adverse childhood experiences such as rape, torture, and constant abuse may transform a child into a criminal that cannot be easily transformed.

Antisocial Peers and Gang Involvement

The environment in which a child lives has a massive impact on their likelihood of committing a crime more than once. Ortega-Campos et al. (2016) explain that some neighborhoods have high prevalence of crime than others in the country. Studies have identified Baltimore, Indianapolis, Tulsa, and Kansas City as some of the most dangerous places for children in the United States (Walker & Bishop, 2016). Crime rates are very high in these places and authorities are almost overwhelmed as they have to stretch their limited resources. Cases of drug trafficking and use, rape, robberies, burglaries, auto theft, and homicide cases are way beyond the national average in these neighborhoods. Children grow up learning how to use guns and other dangerous weapons to achieve selfish goals.

Gang involvement is common in these places, which makes it highly common for these children to be repeat offenders. Wolff and Balglivio (2017) explain that joining gangs is one of the few ways that adolescents in these neighborhoods can feel safe. Some of them lack the care and protection of their parents, and as such, these gangs are the only option they are left with (Walters, 2016). When they are released from juvenile detention, they have to rejoin these criminal outfits because they lack any other option. In such cases, it is almost impossible to fight juvenile recidivism because it has become their way of life. They believe that they have to obey the gang leaders to ensure that they are safe.

Peer Rejection and Bullying

Minors tend to be sensitive as they grow up, and one of their main concerns as they grow into adolescence is the need to be accepted by their peers. The desire to belong and be loved by colleagues at school and at home can be so strong that these children might be willing to do everything for it (Miura & Fuchigami, 2020). When abusing drugs is seen as a cool practice by peers, they can easily be swayed into such a practice because they want to be accepted. They fear rejection so much at that age that they would rather be involved in crime than face it.

Bullying is another common problem in the society that can make a minor to commit a crime repeatedly. Children tend to respond to bullying differently depending on their temperament and what they learn from home. When a child learns that they can use violence against those who bully then, then they can engage in such violent acts repeatedly even after going through a correctional facility (Lee et al., 2019). Others may be forced to join criminal gangs and be willing to commit crime as their only way of avoiding bullying. Probation officers who fail to understand these environmental challenges cannot help these children to overcome challenges that are likely to make them repeat their initial offence.

Individual Factors

Juvenile recidivism may be caused by personal factors not associated with the environment in which a child lives. According to Zane et al. (2020), some children live in some of the safest neighborhoods in the country where they have the best opportunity to succeed in life. However, they fail to meet such expectations as they become involved in drug abuse and other criminal activities. Despite the effort that their parents, teachers, and the community put to help them transform, they degenerate to become some of the most dangerous criminals in the society (Baglivio et al., 2018). It was necessary to identify the individual traits likely to make a minor to become a repeat offender even after being taken through the correctional facilities.

Mental Disorders and Neuropsychological Issues

Mental disorders have been identified as one of the common reasons why some children engage in criminal act. These mental and neurological disorders may make some of these minors to behave in deviant ways because of forces beyond their control. Wibbelink et al. (2017) identify intermittent explosive disorder as one of the mental problems that some minors struggle with in some cases. It involves repeated episodes of impulsive aggression and violent behavior or outbursts. A minor provocation would be responded to with disproportionate force that is not justified. Such a child can be very violent with their peers, teachers, or even parents when they feel that they have been provoked.

Pyromania is another serious mental disorder that may make a child to commit repeat offence even after an arrest and incarceration. In this case, the child will be having an irresistible desire to set things on fire (McReynolds et al. 2010). When the desire sets in, the individual becomes restless and would try to find ways of achieving their goal. Those who are regularly involved in arson have been diagnosed with this mental disorder. Kleptomania is another common mental disorder that affect a section of the society (Wylie & Rufino, 2018). Such individuals are often overwhelmed by the desire to steal, regardless of the profitability or need. Their satisfaction comes from the knowledge that they have taken something that is not theirs without paying for it. A juvenile with such a problem can be arrested and jailed severally without having their habit changed.

Oppositional defiant disorder has been identified as another neuropsychological issue that may be responsible for juvenile recidivism. Such children exhibit persistent anger, defiance, irritability, and vindictiveness that make it impossible for them to relate well with peers, teachers, and family members (Baglivio et al., 2017). They easily become angry every moment they encounter an individual with an idea different from theirs, and sometimes they can become violent. Nymphomania is also another problem where one has an irresistible desire for sex. Such teenagers are likely to be involved in crimes such as prostitution or rape. These mental disorders should be identified and properly managed for a child to overcome a given antisocial behavior.

Personality Traits

The personality trait of a juvenile may also define their likelihood of becoming repeat offenders. According to Cacho et al. (2020), personality trait refers to an individual’s characteristics, behavior, and thought patterns. Some traits make one more likely to be involved in crime while others tend to make an individual to be a law-abiding citizen. High impulsivity is one such trait that may make an individual to engage in crime. Such a juvenile would take impulsive actions without thinking much about the consequences. They tend to become conscious of their actions after they have committed the crime.

Agreeableness is a trait that many consider positive, but it can have negative consequences if it is not managed properly. Such an individual would always want to avoid conflicts and would easily accept the opinion of others just to ensure that they remain friendly (Lee et al., 2019). Such a trait is positive as long as they know when to say no. When a colleague wants them to be involved in crime, they should not allow their friendliness to override the desire to do wrong things. Some minors are involved in crime primarily because they fear hurting others. They feel that they have a responsibility not to disappoint their peers or those who are close to them.

Substance Abuse

The United States remains one of the most attractive markets in the world for hard drugs. According to Darling-Hammond et al. (2020), despite the effort that the government has put in place to fight the sale and use of these drugs, substance abuse still remains one of the most common socio-economic and political problem in the country (Papp et al., 2016). It affects youths irrespective of their social background or the neighborhoods from which they come. High schools and colleges are some of the most common places where youths tend to learn how to use and become addicted to the drugs. Cocaine, meth, marijuana, heroin, and prescription drugs are commonly abused by minors across the country (Wolff & Balglivio, 2017). Measures that the government has put in place have not been very effective in dealing with the problem.

Once a minor is addicted to these drugs, they can easily engage in crime to generate money to purchase them. According to Hirsch et al. (2018), the problem that often arise is that these children do not have a steady flow of income. They rely on small amounts of money for upkeep that they receive from parents or guardians. When the money is not enough to fund their addiction, they are forced to engage in criminal activities. They commit crimes such as theft, robbery with violence, burglary, or even murder just to ensure that they acquire what they desire. Some of them are recruited to facilitate trafficking and sale of these drugs in schools and colleges across the country.

Educational Issues

Education is often considered as the most important tool that can be used to fight the problem of juvenile delinquency within a country. Mulder et al. (2011) believe that when children are effectively engaged in school work, they are less likely to have time to be involved in criminal activities or behavior that may be self-destructive such as abusing drugs and alcohol. The education system in the country has gone through transition for the past several years in an effort to ensure that quality is improved. However, some studies have revealed that some learning institutions have failed to meet expectations of stakeholders (Fine et al., 2018). Instead of being institutions where learners can gain new skills, these institutions have become places where juveniles are introduced to the use of hard drugs. They also learn how to engage in criminal acts such as robbery and auto theft (Hirsch et al., 2018). Lack of proper monitoring of actions of these students and guidance has been blamed as one of the main reasons why these institutions are becoming dangerous instead of being of assistance to learners.

Race and Ethnicity

Race has remained one of the controversial topics when discussing juvenile delinquency and juvenile recidivism in the United States. As Doekhie et al. (2017) explain, the race of an individual has nothing to do with their likelihood of engaging in crime. However, systemic issues in the country has created a gap between whites and blacks, including other minorities in the country. According to Zane et al. (2020), census conducted in the recent past has revealed that some of the most dangerous neighborhoods in the United States are dominated by blacks and other minority groups.

Racism is becoming a problem when fighting juvenile recidivism in the country. An African American teenager is likely to be given a custodial sentence than a white colleague who committed the same crime. Once in prison, they are subjected to mental torture where they are constantly reminded that they are inferior to whites and are more likely to end up in crime (Walker & Bishop, 2016). There is also the wrong perception in this society that blacks are more likely to become drug traffickers and users than other races in the society. When a child grows up in such an environment, they embrace these antisocial practices because they are taught it is a common practice among people of their race.

The criminal justice system is not the only problem when it comes to tackling racism related to juvenile recidivism in the country. The society has failed to create an environment where everyone can exploit opportunities in the nation. According to Darling-Hammond et al. (2020), blacks still struggle to enroll in some of the best schools and colleges in the country. Cases of police brutality against a section of the society is also creating bitterness among the affected group. It creates a feeling that the American society is not fair, and that the only way through which one can have justice is to use criminal means. The bitterness that racism is creating in the society is making some of these minors to consider engaging in unlawful activities.

Socioeconomic Factors

Socio-economic issues have been identified as being risk factors associated with juvenile recidivism. The United States has the largest economy in the world, with a very high per capita income when compared with other nations around the world. However, it is worrying that millions of people in this country live in absolute poverty (Auty & Liebling, 2019). Cases of homelessness and people having to rely on government to access basic needs, including food, are becoming increasingly common. Many are faced with the situation where they have to decide whether to pay for basic needs such as food and shelter or medical needs. Some children have to rely on government support to achieve their educational needs.

Children from poor background are more susceptible to crime than their colleagues from financially empowered backgrounds. They desire to own things that their colleagues have and lead a better life. Unfortunately, their parents cannot provide them with these needs because of their financial challenges (Baglivio et al., 2018). These minors are often tempted to engage in criminal activities to achieve what they want. They can become drug peddlers in school, pimps, prostitutes, robbers, or any other crime that can enable them have access to the money they need. When they are arrested, given a custodial sentence, and later released, they are likely to go back to crime because that is the only way they believe they can have access to the income that they need.

Prevention Programs and Strategies

Juvenile recidivism is a major problem that stakeholders in the criminal justice system are struggling to address at the moment. It is apparent that the current mechanisms are not delivering the expected outcome. As Zane et al. (2020) explain, cases where minors commit offences such as drug trafficking, drug peddling, theft, or burglary cannot be completely eliminated in the country. However, the juvenile justice system is focused on ensuring that once such a child is arrested and taken through courts and correctional facilities, they do not end up repeating the same or even worse offences. Studies have revealed that in most of the cases, these juveniles leave these correctional facilities worse criminals than they were before (Lee et al., 2019). They learn new skills of robbery and other criminal acts through friends that they meet in these institutions. They also develop new friends who they can work with to commit more serious offences. It means that these institutions become platforms through which they acquire new knowledge of committing serious offences.

The fact that these children leave correctional facilities more determined and capable of committing major crimes means that the juvenile justice system is achieving the opposite of what it was intended. Bucko et al. (2018) explain that stakeholders in the justice system are faced with a huge dilemma when handling child offenders. Some crimes can only be punished appropriately through custodial sentence. It is the only way of deterring others from committing the same offence. However, the process is achieving the opposite goal of the vision that defined the development of juvenile justice system. Scholars have proposed ways of overcoming the dilemma and ensuring that system achieves its intended goal. In this section of the report, the goal is to discuss various prevention program strategies that can be used to overcome the problem of juvenile recidivism in the country.

School-Based Programs

Addressing the problem of juvenile recidivism requires a multi-stakeholder and multi-sectorial approach. It requires the involvement of the entire society in different capacities. Learning institutions are some of the best entities that can help in fighting the vice and ensuring that minors lead a responsible life that is free from crime (Auty & Liebling, 2019). Scholars have always recommended the use of these institutions to help learners to understand what is expected of them and how to avoid unlawful acts. In most of the cases, children spend most of their days at school. As such, programs can be created where they are targeted with information about dangers of crime, how to avoid wrong companies, how to address and report bullying and gang activities, and benefits of remaining law-abiding citizens.

Suggestions have been made to ensure that the curriculum is revised to capture a broad range of issues that affect lives of these children. Voorveld et al. (2018) note that most of these minors are forced into crime because of poverty, bullying, rejection, peer pressure, and other challenges discussed in the section above. Although it is true that the curriculum cannot address issues such as poverty and mental disorders, it can help in empowering these children on how to manage other problems like peer pressure and bullying. Students need to learn how to deal with numerous challenges that they face in their lives without resorting to crime. Learning institutions should put in place systems that will protect juveniles from any form of bullying while they are in school.

Mechanisms may also be needed for them to report bullying that they face when they are out of school so that appropriate measures can be put to address the problem. These institutions need to empower children so that they can understand that life in crime does not solve the challenges they face in life. They need to learn about self-esteem and the fact that they do not need to engage in crime to be accepted by their peers. Schools are in the best position to create awareness among minors about dangers of crime. Teachers can help learners to understand the fact that the short-term victory and pleasure associated with crime often have devastating long-term consequences.

Ensuring the Continuity of Education

Custodial sentences cannot be completely avoided when handling child offenders in the juvenile justice system. However, Hancock (2017) emphasizes the need to ensure that there is continuity of education while such a child is in custody and after release. While in correctional facilities, education can be continued in the form of cell-to-classroom coordinators. These coordinators can visit these young inmates regularly to ensure that they continue with their education. Alternatively, some scholars have recommended having these correctional facilities for children transformed into approved schools with a standard learning environment (Rivera, 2020). A part of the correctional officers should be teacher who will ensure that inmates can continue with their education.

The aim of maintaining continuity if education is to ensure that once these children are released, they can join their peers and resume classes. Many of these juvenile offenders often consider dropping out of school after leaving prison because of lack of continuity in learning. They find it difficult resuming classes after staying away in prison for more than a year. The fact that their colleagues are ahead of them also discourages them further from going back to class. Such challenges can be addressed by ensuring that these institutions facilitates continued learning for these children while they are in custody.

Recommendations for Successful Back-to-School Integration

When a minor is released from the correctional facilities after completing their term, it is always the expectation of stakeholders in the criminal justice system that they would resume their classes. However, studies have revealed that most of them rarely go back to school, especially teenagers who are incarcerated for more than two years (Kubek et al., 2020). Most of them find it difficult going back to class after several years of staying out of the education system. The fear of stigmatization by their colleagues and the desire to demonstrate that they are tough often lead them to decline further into life of crime instead of becoming responsible teenagers.

Having successful back to school integration programs is critical in enhancing the ability of these children to lead responsible lives after prison. Facilitating the continuity of education while a child is in a correctional facility is just one aspect of the program. The next and very important stage is to ensure that they are integrated back to the society and school as soon as they are released. Bucko et al. (2018) strongly recommend a change of environment for such a minor. The goal is to ensure that the child will start a new life with new friends who cannot influence them back to the life in crime. The new environment also helps in avoiding the problem of victimization and intimidation by their colleagues who knew that they were in prison.

Law Enforcement-Based Programs

Law enforcement agencies still have the primary role of ensuring that minors who engage in crime are effectively reformed. Darling-Hammond et al. (2020) believe that one of the biggest challenges that the American society faces is the perception that has been created about law enforcement officers. There is a deep mistrust, fear, and even hatred that the society has towards police officers. According to Ryon et al. (2017), for a long time, African Americans have developed deep-rooted mistrust towards law enforcers. They are justified to do so because these officers have often abused their powers for centuries. It is more likely that an African American man would die in the hands of officers than a white. Cases of the use of lethal force even when it is not necessary have often been reported, further straining the relationship between some members of the society and these agencies. As such, minors learn to fear and hate these officers instead of viewing them as a source of security.

It is necessary to have programs that would help change the negative perception that the society has towards law enforcement agencies. Voorveld et al. (2018) argue that the only way through which police officers can work closely with juvenile offenders is to have trust. The trust can only be created if the society views the agency as one that is committed to fighting crime fairly and professionally without targeting a section of the society. Such reforms should start during the training of these officers. They need to learn how to be impartial when enforcing the law. Strict policies that prohibit unnecessary use of force and abuse of power also needs to be implemented. Vidal et al. (2019) also believe that police officers need to work closely with learning institutions to create a positive relationship with minors. They can create a new perception that children have towards them.

Mediation and Restorative Justice Interventions

Law enforcement programs may not necessarily require incarceration of a minor once they commit a crime. Sometimes organizing meetings between the offender and the victim, often with their family members may be the best way of addressing the problem (Bouffard et al., 2017). When a child is arrested for the first time of a crime of non-violent theft, the officers involved can summon the family of the child, ensure that the stolen item is returned to the owner, and that proper guidance is given to the child so that they do not repeat the same offence again. Restorative justice is often seen as effective ways of avoiding custodial sentences for minors (Suzuki & Wood, 2018). It ensures that the victim is effectively compensated and that the offender is made to understand that their action was wrong and unfair. The intervention made in this case is meant to minimize cases where first-time offenders are sent to jail (Wong et al., 2016). When implementing such a program, it is essential to ensure that there is fairness irrespective of one’s race. Such restorative justice should be used indiscriminately to ensure that the targeted goals are realized.

Behavioral/Mental Health Treatment

Juvenile delinquency and recidivism may be caused by mental health problems as discussed in the section above. Some of these minors have to battle with an irresistible desire to steal or be involved in arson. It does not matter how many times such a child is arrested and taken to a correctional facility if the problem is not addressed through proper treatment. Custodial sentence may only help the society temporarily by ensuring that they are locked away. However, when they are released, they are more likely to commit the same crime and with greater sophistication than before because their problem is mental. The following are some of the ways in which these minors can be assisted so that they can overcome their problem.

Substance-Abuse Treatment

When a child is suffering from drug addiction, it is always critical to help them overcome the problem without necessarily taking them to prison. Belenko et al. (2017) note that various rehabilitation centers across the United States have developed effective means of helping their patients to overcome addiction. Substance abuse treatment helps the affected individual to overcome dependency on drugs. They can easily lead normal lives once they leave the rehabilitation center. Voorveld et al. (2018) explain that a significant number of child offenders are forced into crime because of drug addiction. They lack a steady flow of income but their body system have become reliant on drugs. They have to steal or engage in similar crimes to enable them purchase cocaine, marijuana, heroin, or alcohol. When they become non-dependent on drugs, the need to steal or rob people will be eliminated. They will have the opportunity of leading a responsible life as teenagers with specific life goals that they would need to achieve.

Specialized Treatment Programs for Juvenile Sex Offenders

When a child is diagnosed with a specific mental or behavioral problem, they may need a specialized treatment program that addresses the specific problem. Kettrey and Lipsey (2018) argue that a problem such as one who is a kleptomaniac or nymphomaniac cannot be addressed through the criminal justice system. Instead, such an individual require psychotherapy to help them overcome the condition. First, they need to understand and accept the fact that they have such a condition. They also need to know how their mental problem is affecting them and the society negatively. The knowledge will help them accept the fact that they need to change from actions and behavior that is hurting the society.

The therapy should focus on empowering these juveniles to overcome their mental problem. They should know when the urge is becoming uncontrollable and what they can do to overcome it. When one has a problem with fire, a therapeutic solution can be developed so that they engage in an alternative activity such as physical exercise. They can learn how to replace the dangerous act with an alternative that is constructive to them and the society (Auty & Liebling, 2019). They also need to have confidants they can talk to every time the temptation becomes strong. Such a confidant can help them distract the negative thoughts and ensure that they do not act impulsively.

Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment

Juvenile offenders sometimes require cognitive behavioral treatment instead of facing custodial sentences where they have to spend time in correctional facilities. In such institutions, they can learn social skills, decision-making, empathy development, anger management (Mathys, 2017). As discussed in the section above, some of these children grow up in highly toxic environments and families where they learn that every conflict can only be addressed effectively through violence. Cognitive behavioral treatment can help recondition their thoughts. They need to learn social skills, especially when it comes to resolving conflicts. Anger management is one of the cognitive skills that can significantly reduce cases of violence among juveniles. They also need decision-making skills so that they can know when sometimes is trying to use them to achieve selfish goals such as to peddle drugs. The goal is to empower these children so that they can know when and how they need to take a step back and avoid taking an action that may subject them to legal problems and involvement of law enforcement agencies.

Aggression Replacement Training (ART)

One of the common cognitive behavioral treatment that is effective is the aggression replacement training. Some of these juveniles might have grown up knowing that the best way of solving conflicts is through the use of aggression. Such individuals are highly irritable and use violence to ensure that they acquire what they want (Brännström et al., 2016). The ART therapy focuses on training these children to replace the aggressive behavior with something else that is less destructive. For instance, they can be trained to engage in physical exercise such as jogging every time they become agitated and are tempted to be aggressive. The energy that would otherwise be used in a fight will be put into constructive use. By the end of the exercise, they will be drained physically and will not have the desire to engage in physical fights.

The more they practice this behavior, the less likely they are to be aggressive. Bucko et al. (2018) explain that when using this therapy, it is essential to explain to these children why it is important for them to redirect their energy to something positive instead of being physically and verbally aggressive. They need to realize that their aggression is a threat to their wellbeing and the safety of others close to them. One challenge that a trainer can face is the feeling among these minors that being less aggressive is a sign of weakness. Such a mentality should be changed and they need to learn that sometimes avoiding war is the best demonstration of strength.

Dialectical Behavioral Theory (DBT)

The DBT therapy is widely used to help manage negative thoughts that an individual could be struggling with. Such thoughts could be as a result of experiences that a child has had, making them feel suicidal (Augustyn et al., 2019). The therapist would need to understand the cause of these self-destructive thoughts before helping the minor to have a positive view of life. The process may require changing the environment in which the child lives when it is possible. The country has existing laws that may justify taking away a child from the guardianship of a parent if it is established that the environment is toxic for the wellbeing of the minor.

Family-Based Programs

The immediate family of a child has the primary role of helping their child to overcome juvenile recidivism. In most cases, children embrace deviant behavior because of events happening at home. It may be because of the neglect of the parent or oppression that they are constantly subjected to by a family member. Changing the environment at home and giving the child the necessary attention, love, and guidance may be all that is needed to help them overcome their condition. The following are some of the family-based programs that can help reduce juvenile delinquency.

Multi-systemic Therapy (MST)

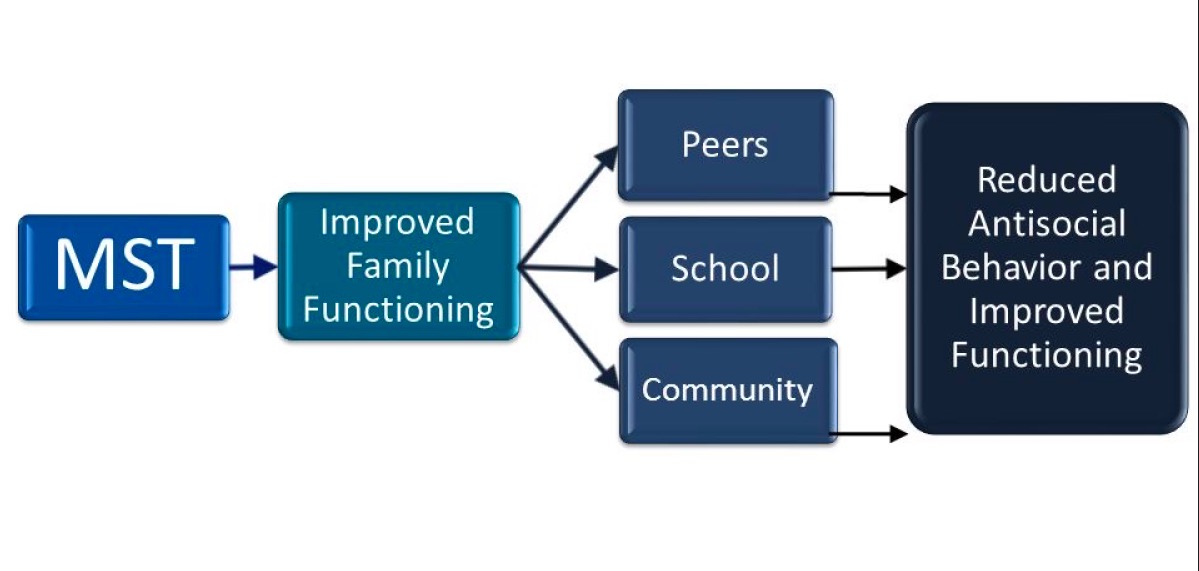

Young people who often find themselves committing various forms of crime might need help using the MST model. As shown in figure 1 below, this multi-systemic therapy brings together various stakeholders such as the family, peers, school, and the community with the goal of reducing antisocial behavior among adolescents. The family is given the primary goal of facilitating the needed change (Connell et al., 2016). Parents and siblings are in the best position to know if a minor is having a sudden change of behavior. When a child becomes a perennial offender, family members can assist the child by providing love and support that they need to overcome the mental or behavioral challenge that they are going through (Henggeler & Schaeffer, 2016). They should remind these children that it is not necessary to seek validation from wrong groups to feel loved and accepted.

Functional Family Therapy (FFT)

The functional family therapy is another approach that can be used at a family level to help reduce juvenile recidivism in the United States. Humayun et al. (2017) explain that parents are the initial teacher and role models of their children. When a child lives in a functional family, they learn values and virtues that are less likely to turn them into criminals. Robbins et al. (2016) argue that parents have the primary role of ensuring that they provide the example that their children need to become responsible adults. Abusing alcohol and drugs openly before a child is a clear demonstration to them that it is normal to use the substance. Changing the perception of such a child may not be easy because they learn from these parents. In cases where it is noted that the current family is incapable of protecting the child because it is dysfunctional, it may be necessary to find adoptive parents for the child.

Parenting with Love and Limits Program

The approach that one takes in upbringing a child may influence their behavior. Keeping youth with their families is always the goal of the juvenile justice system although sometimes it becomes unavoidable to give custodial sentences (Ryan et al., 2013). When a child is released to the parent after serving a sentence or when they receive a non-custodial sentience, it is the responsibility of the family to ensure that they receive the emotional and material support they need to lead a normal life. Parenting with love and limits is a popular program that emphasizes the need for a parent to show care and concern for their child but at the same time know when to be strict on them. They should not spoil the child because of the love they have for them, but at the same time these minors should not feel neglected.

Community-Based Programs

The community also has a role to play in fighting juvenile recidivism in the country. As Bucko et al. (2018) observe, most parents have to spend most of their daytime at work to ensure that they provide basic needs for their families. Some have to take two or three jobs to ensure that they earn enough for living. In such cases, it is possible that the child may develop deviant behavior without the knowledge of the parent. The community has a role to play in identifying these antisocial behaviors and acting appropriately to help the child. The following are some of the community-based programs which have proven effective in managing deviant behavior among juveniles.

Mentoring Programs

One of the best ways of fighting juvenile recidivism is by promoting mentoring programs in the community. Having role models who engage minors at a personal level has proven to have a massive influence on their behavior (Tolan et al., 2014). The program is effective when celebrities and successful members of the society are involved in such mentoring programs. When a child interacts with people they admire, they will have the drive to achieve similar success. They can be influenced easily to avoid engaging in criminal acts. The mentors should help these juveniles to understand the benefit of obeying the law and being focused on achieving specific goals in their lives.

Library Media Program

Minors sometimes engage in crime because they have free time when they are not in school. Formby and Paynter (2020) argue that it is important to have library media programs where children can spend time reading relevant materials instead of idling during holidays. Instead of spending time with wrong company, these children will have the opportunity to concentrate on books within their community. Public libraries in the United States should be made attractive through integration of technology for these children to have access to materials that they need. However, care should be taken to limit access to specific websites that may expose them to adult materials of information that may intoxicate their mind. Mentors should encourage these juveniles to spend more time in the library to ensure that they gain relevant knowledge that they need to lead successful lives.

Aftercare Program/Intensive Aftercare

Aftercare programs are designed to help an individual to recover from a given problem and to avoid relapse. When a juvenile is released from a correctional facility, the goal of all stakeholders involved in the correction process is that the child will not relapse to crime. However, the goal can only be realized if proper care is given to the child to help them overcome emotional and mental challenges (James et al., 2016). Victimization is often one of the biggest challenges that such children face when they are released. Some of their peers who can help them reform would avoid them when it is known that they have been through prison.

The rejection may force them to go back to criminal gangs because of the desire for acceptance. The community has a major role to play in fighting victimization of juveniles who have gone through correctional facilities. They need to be accepted and supported so that they can become responsible members of society. People must realize that when these children are not assisted, they may become hardened criminals and victims of their criminal acts will be individual members of the community. Helping in the process of reforming the child is part of enhancing a secure community where people understand and value the rule of law.

Barriers to Healthcare during Re-Entry

When integrating juvenile offenders back to the society after saving their time in a correctional facility, many challenges may emerge, one of which is barrier to healthcare. Such challenges may also cause further frustrations to the minor, which may force them to go back to their criminal past (Barnert et al., 2020). It is necessary to have a clear program that defines how these minors would have access to services that they need to lead a normal life. Their criminal record should not be the basis upon which they are denied services that they need. It is a normal practice for the courts to retain their criminal records just in case it becomes of use when they repeat a similar crime. However, the information should not be the basis upon which they are denied entry into specific schools, internship programs, healthcare cover or such other similar opportunities that can help in transforming their lives. Some insurance companies are currently using criminal records to assess those who they cover. Such practices should be discouraged, especially if it would discriminate against minors who are trying to reform.

Wraparound

Having wraparounds is another effective community-based approach of addressing the problem of juvenile recidivism in the community. Having team meetings involving not only an offender and their family but also neighbors, therapists, teachers, parole officers, clergy, and other relevant stakeholders is essential (Pullmann et al., 2006). It creates a sense of security and care for the child. It is a reminder to them that the society cares and is willing to do everything to support them. Such meetings should not dwell on the criminal past of the child. Instead, the focus should be on how to create an environment that is supportive enough to enhance growth.

Behavioral Treatment Services

The community can organize for some of these troubled children to receive behavioral treatment services at specific facilities. As explained in the previous section of this paper, a child may develop a deviant behavior because of a mental problem or the environment in which they leave. They become troubled mentally, making it easy to abuse drugs and engage in trafficking (Aalsma et al., 2015). Such children should not be taken to correctional facilities, especially if they are first offenders. Instead, they should be given behavioral treatment services to help them overcome their problem.

Depending on the cause of the problem and its severity, the program may take different approaches. If it is established that the environment at home is still toxic and limits the ability of the child to recover, the therapist should recommend relocation. Such services should be made easily accessible to all members of the community irrespective of their financial capacity. They can also be made available in rehabilitation centers where these juveniles are assisted to overcome their addiction to drugs or alcohol. During the treatment program, the rehab facilities can also help in transforming the behavior of the child. Factors that led them to drug use and other crimes should be investigation. The therapist should then help them redefine their ways in life so that they can become responsible citizens.

Desistance Focused Treatment

The program is designed to reduce risk factors of an adolescent going back to a criminal past. As Menon and Cheung (2018) explain, it focuses more on treatment than on the social support. It is based on the premise that some of these children have underlying mental conditions that cannot be managed through serving time in prison or receiving the social support. While it is true that juvenile offenders need proper social support to overcome the challenge they face, Doekhie et al. (2017) note that some medical intervention may be necessary. If one is an addicted arsonist, mental reconditioning may be the best solution to overcoming the problem. It may require a medical process where the individual’s uncontrollable desire to burn down things are controlled.

A young child may also engage in prostitution because of the immense urge to have an intercourse. Given that the desire is not something they can control with the help of the social support, they might need some form of treatment to help suppress such feelings. Facilities offering such treatment programs should be widespread within the community and they should be able to operate without necessarily admitting their patients. Some people may not accept that they have such a condition. It should be possible for such individuals to have access to services that they need without their identity being revealed to members of the public.

Summary

The extensive review and synthesis of research conducted in this study reveals that juvenile recidivism is a major problem in the United States despite the effort that has been made by different stakeholders to address it. The study has identified various factors that contribute to the problem in the country. It is apparent that some of the main causes and risk factors leading to juvenile recidivism include as family dysfunction, poor academic achievement, peer pressure, rejection, and drug abuse. A child in a dysfunctional family is highly likely to become a delinquent because of the negative forces they are exposed to regularly. Poverty, the desire to be accepted among peers, and the level crime within a given community also have a significant influence on juvenile recidivism.

The study provided an analysis of most successful programs and approaches that can be used to address the problem. They were classified as school-based programs, law-enforcement based programs, behavioral/mental health treatment, cognitive-behavioral treatment, family-based programs, and community-based programs. The analysis identified various similarities and differences in these programs. All of them are focused on transforming the delinquents into responsible citizens through various means to ensure that they do not relapse into the life of crime. The main difference noted in the comparative analysis of these programs is that some emphasize the need for social support when handling these minors while others focus on offering treatment as the best solution. Each program is suitable for managing specific condition.

Programs effective at reducing juvenile recidivism focus on the specific problem that a child faces. One has to understand the modifiable and the unmodifiable risk factors that have to be addressed. The behavioral challenges are modifiable through various programs meant to help the child lead a responsible life. On the other hand, some of these problems are unmodifiable through social support, such as that of a serial arson. The irresistible drive that forces them to commit such crimes would require some form of treatment besides the social support. As shown in the paper, the problem cannot be addressed by an individual or a section of society. It requires the involvement of everyone to ensure that a lasting solution is found to help address the problem of crime among minors.

Families have their roles that they have to play to help their child lead a normal responsible life. Schools, the community, law enforcement agencies, the justice system, and celebrities all have to work as a unit to support these children. The study also shows that it is now necessary for the government to reassess the juvenile justice system and identify major weaknesses that needs to be addressed. It is clear that juvenile correctional facilities have failed to transform children as was envisaged when they were created. Incarcerated juveniles are more likely to commit the same or worse crimes that those who received non-custodial sentences. The following recommendations should be considered by the government, community, families, and future scholars.

- The government should enact new laws that will help in reforming the juvenile justice system in the country. The research reveals that the current system is not effective in addressing juvenile recidivism.

- Families and communities should work together, combining various approaches and programs of reducing juvenile recidivism, to help minors overcome problems they face in life.

- Celebrities and other public figures should be actively involved in the reform programs for these juvenile offenders.

- Future scholars should focus on identifying reasons why incarcerated children are likely to commit serious crimes after their release than those who receive non-custodial sentences.

References

Aalsma, M. C., White, L. M., Lau, K. S., Perkins, A., Monahan, P., & Grisso, T. (2015). Behavioral health care needs, detention-based care, and criminal recidivism at community reentry from juvenile detention: A multisite survival curve analysis. American journal of public health, 105(7), 1372-1378. Web.

Augustyn, M., Thornberry, T., & Henry, K. (2019). The reproduction of child maltreatment: An examination of adolescent problem behavior, substance use, and precocious transitions in the link between victimization and perpetration. Development and Psychopathology, 31(1), 53-71. Web.

Auty, K., & Liebling, A. (2019). Exploring the relationship between prison social climate and reoffending. Journal of Justice Quarterly, 37(2), 358-381.

Baglivio, M. T., Wolff, K. T., Piquero, A. R., DeLisi, M., & Vaughn, M. G. (2017). Multiple pathways to juvenile recidivism: Examining parental drug and mental health problems, and markers of neuropsychological deficits among serious juvenile offenders. Criminal justice and behavior, 44(8), 1009-1029.

Baglivio, M., Wolff, K., Piquero, A., DeLisi, M., & Vaughn, M. (2018). The effects of changes in dynamic risk on reoffending among serious juvenile offenders returning from residential placement. Journal Justice Quarterly, 35(3), 443-476.

Barnert, E. S., Abrams, L. S., Lopez, N., Sun, A., Tran, J., Zima, B., & Chung, P. J. (2020). Parent and provider perspectives on recently incarcerated youths’ access to healthcare during community reentry. Children and Youth Services Review, 110(3), 4-11. Web.

Belenko, S., Knight, D., Wasserman, G. A., Dennis, M. L., Wiley, T., Taxman, F. S., Oser, C., Dembo, D., Robertson, A., & Sales, J. (2017). The Juvenile Justice Behavioral Health Services Cascade: A new framework for measuring unmet substance use treatment services needs among adolescent offenders. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 74, 80-91. Web.

Bouffard, J., Cooper, M., & Bergseth, K. (2017). The effectiveness of various restorative justice interventions on recidivism outcomes among juvenile offenders. Youth violence and juvenile justice, 15(4), 465-480.

Brännström, L., Kaunitz, C., Andershed, A. K., South, S., & Smedslund, G. (2016). Aggression replacement training (ART) for reducing antisocial behavior in adolescents and adults: A systematic review. Aggression and violent behavior, 27(1), 30-41.

Bucko, J., Kakalejčík, L., & Ferencová, M., & Wright, L. (2018). Online shopping: Factors that affect consumer purchasing behavior. Journal Cogent Business & Management, 5(1), 2-8. Web.

Cacho, R., Fernández-Montalvo, J., López-Goñi, J. J., Arteaga, A., & Haro, B. (2020). Psychosocial and personality characteristics of juvenile offenders in a detention centre regarding recidivism risk. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 12(2), 69-75.

Connell, C. M., Steeger, C. M., Schroeder, J. A., Franks, R. P., & Tebes, J. K. (2016). Child and case influences on recidivism in a statewide dissemination of multisystemic therapy for juvenile offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(10), 1330-1346. Web.

Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2020). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Journal Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97-140.

Doekhie, J., Dirkzwager, A., & Nieuwbeerta, P. (2017). Early attempts at desistance from crime: Prisoners’ prerelease expectations and their postrelease criminal behavior. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 56(7), 473-493.

Fine, A., Simmons, C., Miltimore, S., Steinberg, L., Frick, P. J., & Cauffman, E. (2018). The school experiences of male adolescent offenders: Implications for academic performance and recidivism. Crime & Delinquency, 64(10), 1326-1350.

Formby, A. E., & Paynter, K. (2020). The potential of a Library Media Program on reducing recidivism rates among juvenile offenders. National Youth-At-Risk Journal, 4(1), 14-21. Web.

Hancock, K. (2017). Facility operations and juvenile recidivism. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 6(1), 1-10.

Henggeler, S. W., & Schaeffer, C. M. (2016). Multisystemic therapy: Clinical overview, outcomes, and implementation research. Family Process, 55(3), 514-528. Web.

Hirsch, R. A., Dierkhising, C. B., & Herz, D. C. (2018). Educational risk, recidivism, and service access among youth involved in both the child welfare and juvenile justice systems. Children and youth services review, 85(1), 72-80.

Humayun, S., Herlitz, L., Chesnokov, M., Doolan, M., Landau, S., & Scott, S. (2017). Randomized controlled trial of Functional Family Therapy for offending and antisocial behavior in UK youth. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(9), 1023-1032. Web.

James, C., Asscher, J. J., Stams, G. J. J., & van der Laan, P. H. (2016). The effectiveness of aftercare for juvenile and young adult offenders. International journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 60(10), 1159-1184.

Kettrey, H. H., & Lipsey, M. W. (2018). The effects of specialized treatment on the recidivism of juvenile sex offenders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 14(3), 361-387.

Kubek, J. B., Tindall-Biggins, C., Reed, K., Carr, L. E., & Fenning, P. A. (2020). A systematic literature review of school reentry practices among youth impacted by juvenile justice. Children and Youth Services Review, 110(3), 1-6. Web.

Kurlychek, M., & Gagnon, A. (2020). Reducing recidivism in serious and violent youthful offenders: Fact, fiction, and a path forward. Marquette Law Review, 103(3), 877-910. Web.

Lee, W., Moon, J., & Garcia, V. (2019). The pathways to desistance: A longitudinal study of juvenile delinquency. Journal of Deviant Behavior, 41(1), 87-102.

Mathys, C. (2017). Effective components of interventions in juvenile justice facilities: How to take care of delinquent youths? Children and Youth Services Review, 73(2), 319-327. Web.

McReynolds, L. S., Schwalbe, C. S., & Wasserman, G. A. (2010). The contribution of psychiatric disorder to juvenile recidivism. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(2), 204-216. Web.

Menon, S. E., & Cheung, M. (2018). Desistance-focused treatment and asset-based programming for juvenile offender reintegration: A review of research evidence. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 35(5), 459-476.

Miura, H., & Fuchigami, Y. (2020). Influence of maltreatment, bullying, and neurocognitive impairment on recidivism in adolescents with conduct disorder: A 3-year prospective study. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 1(2), 1-10. Web.

Mulder, E., Brand, E., Bullens, R., & Van Marle, H. (2011). Risk factors for overall recidivism and severity of recidivism in serious juvenile offenders. International journal of offender therapy and comparative criminology, 55(1), 118-135.

Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2017). Juvenile Reentry. Web.

Ortega-Campos, E., Garcia-Garcia, J., Gil-Fenoy, M. J., & Zaldivar-Basurto, F. (2016). Identifying risk and protective factors in recidivist juvenile offenders: A decision tree approach. Plos One, 11(9), 1-16. Web.

Papp, J., Campbell, C., Onifade, E., Anderson, V., Davidson, W., & Foster, D. (2016). Youth drug offenders: An examination of criminogenic risk and juvenile recidivism. Corrections, 1(4), 229-245. Web.

Powell, Z., Craig, J., Piquero, A., Baglivio, M., & Epps, N. (2019). Delinquent youth concentration and juvenile recidivism. Journal of Deviant Behavior, 3(1), 1-9.

Pullmann, M. D., Kerbs, J., Koroloff, N., Veach-White, E., Gaylor, R., & Sieler, D. (2006). Juvenile offenders with mental health needs: Reducing recidivism using wraparound. Crime & Delinquency, 52(3), 375-397.

Rivera, R. E. (2020). Identifying the practices that reduce criminality through community-based post-secondary correctional education. International Journal of Educational Development, 79, 102289. Web.

Robbins, M. S., Alexander, J. F., Turner, C. W., & Hollimon, A. (2016). Evolution of functional family therapy as an evidence‐based practice for adolescents with disruptive behavior problems. Family Process, 55(3), 543-557. Web.

Ryan, J. P., Williams, A. B., & Courtney, M. E. (2013). Adolescent neglect, juvenile delinquency and the risk of recidivism. Journal of youth and adolescence, 42(3), 454-465. Web.

Ryon, S. B., Early, K. W., & Kosloski, A. E. (2017). Community-based and family-focused alternatives to incarceration: A quasi-experimental evaluation of interventions for delinquent youth. Journal of Criminal Justice, 51(1), 59-66.

Suzuki, M., & Wood, W. R. (2018). Is restorative justice conferencing appropriate for youth offenders? Criminology & Criminal Justice, 18(4), 450-467.

Tolan, P. H., Henry, D. B., Schoeny, M. S., Lovegrove, P., & Nichols, E. (2014). Mentoring programs to affect delinquency and associated outcomes of youth at risk: A comprehensive meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 10(2), 179–206. Web.

Vidal, S., Connell, C., Prince, D., & Tebes, J. (2019). Multisystem-involved youth: A developmental framework and implications for research, policy, and practice. Adolescent Research Review, 4(1), 15-29. Web.

Vidal, S., Prince, D., Connell, C. M., Caron, C. M., Kaufman, J. S., & Tebes, J. K. (2017). Maltreatment, family environment, and social risk factors: Determinants of the child welfare to juvenile justice transition among maltreated children and adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 7-18. Web.

Voorveld, H., Noort, G., Muntinga, D., & Bronner, F. (2018). Engagement with social media and social media advertising: The differentiating role of platform type. Journal of Advertising, 47(1), 38-54.

Walker, S., & Bishop, S. (2016). Length of stay, therapeutic change, and recidivism for incarcerated juvenile offenders. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 55(6), 355-376.

Walters, G. D. (2016). Neighborhood context, youthful offending, and peer selection: Does it take a village to raise a nondelinquent? Criminal justice review, 41(1), 5-20.

Wibbelink, C. J., Hoeve, M., Stams, G. J. J., & Oort, F. J. (2017). A meta-analysis of the association between mental disorders and juvenile recidivism. Aggression and violent behavior, 33(1), 78-90.

Winningham, D., Banks, D., Buetlich, M., Aalsma, M., & Zapolski, T. (2019). Substance use disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder symptomology on behavioral outcomes among juvenile justice youth. American Journal of Addiction, 28(1), 29-35. Web.

Wolff, K. T., & Baglivio, M. T. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences, negative emotionality, and pathways to juvenile recidivism. Crime & Delinquency, 63(12), 1495-1521.

Wolff, K. T., Cuevas, C., Intravia, J., Baglivio, M. T., & Epps, N. (2018). The effects of neighborhood context on exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACE) among adolescents involved in the juvenile justice system: Latent classes and contextual effects. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 47(11), 2279-2300. Web.

Wong, J. S., Bouchard, J., Gravel, J., Bouchard, M., & Morselli, C. (2016). Can at-risk youth be diverted from crime? A meta-analysis of restorative diversion programs. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(10), 1310-1329.

Wylie, L. E., & Rufino, K. A. (2018). The impact of victimization and mental health symptoms on recidivism for early system-involved juvenile offenders. Law and Human Behavior, 42(6), 558.

Zane, S., Mears, D., & Welsh, B. (2020). How universal is disproportionate minority contact? An examination of racial and ethnic disparities in juvenile justice processing across four states. Journal of Justice Quarterly, 37(5), 817-841.