Introduction

This essay discusses the changing representations of work between 1850 and 1888. Five pieces of art have been used to illustrate these periods while placing each work firmly within its social and historical context.

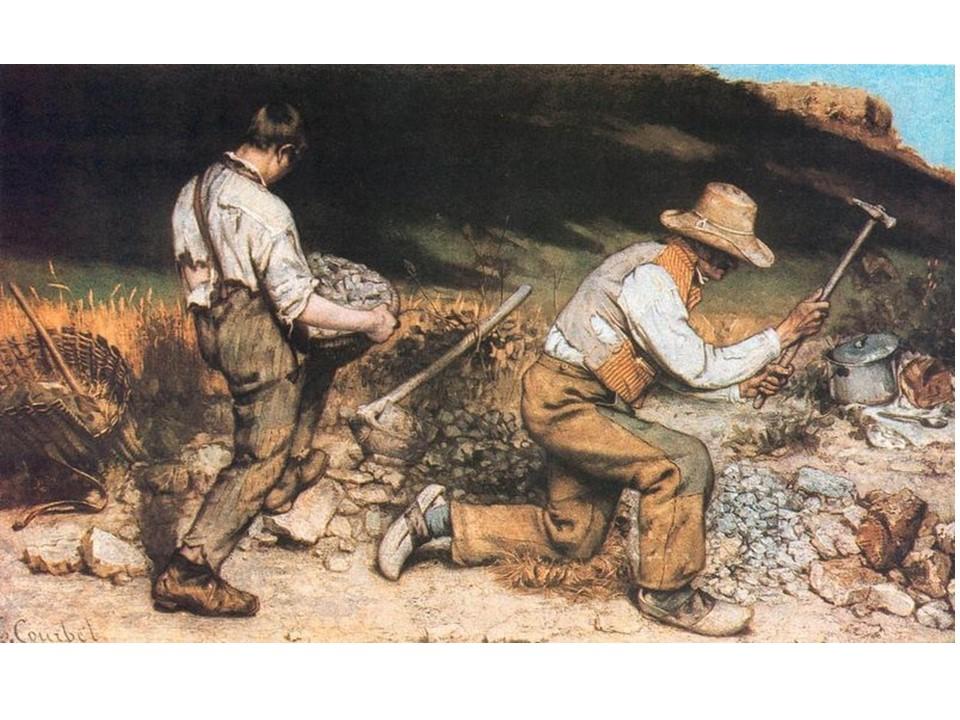

The Stone Breakers by Gustave Courbet (1850)

In the painting depicting two laborers, one youthful and one old, Courbet introduced both a Realist case of regular life and a moral symbol of the real nature of deprivation. Although the painting was motivated by a scene of two men breaking rock for road construction, one of the poorly paid, most strenuous works presumably, the artist ensured that his figures would remain faceless as to make them unknown stand-ins for the poorest of French society in the 1850s. More consideration is given to their filthy, worn-out work garments, their solid, worn hands, and their relationship to the land than to their presence. They are, nonetheless, stupendous in size and appeared calm, appropriate with their readiness to do the menial, unsung work in which the present-day life was found.

The painting of the two laborers, one too boyish for hard work and the other too old for such menial labor, show the sentiments of hardship and weariness that the artist was attempting to depict. Courbet demonstrates the plight of the laborers and disgust for the high society by painting these men with a nobility they deserve.

The Stonebreakers painting was considered as a symbol of the laborer world. In any case, for the painter, it was just a memory of a life he had experienced – two laborers making gravel close to the street. However, the artist’s detractors were sure that Courbet was concentrating on artistic and moral degradation by portraying elements they viewed as disagreeable and insignificant subjects on a great scale. Such works were seen as propagating the unusual malice against appreciated ideas of the ideal and beauty. Realism was seen as nothing other than adversary toward art, and majorities claimed that painting was the origin and the patron of this catastrophe.

Notably, most works of Courbet tend to depict the ordinary lives of peasants and places in society. Courbet’s works of ordinary individuals were attempts to depict the French as a political society with no regard for the poor masses. As such, the artist honestly depicted common persons and places, disregarding the glamor, which many French artists at the time preferred in their paintings. This painting was presented as a leading realist work.

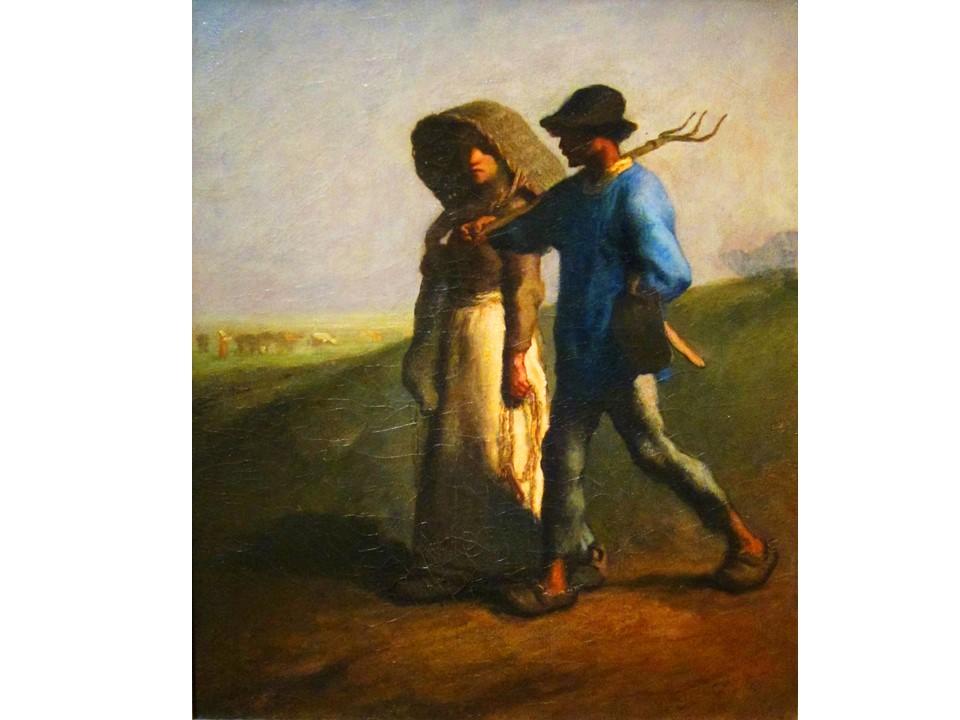

Jean-Francois Millet, Going to Work, 1851

This work of a rural work by Jean-François Millet is broadly viewed as a perfect work of art. Millet’s painting demonstrates a male and a female laborer walking across the field before an early morning sky. The man has a fork behind him, and the woman carries a basket on her head, and it reinforces the artist’s work of Realism.

The style of this work has a place in the genre of Realism. Millet presents the peasant couple as dignified individuals in their contemporary old attires. They appear composed but reflect the struggle of ordinary countryside people. To some extent, Millet displays the peasant plight in the rural agricultural area. As such, many critics considered the painting as a political tool, but the artist insisted that he was not an agitator. From a religious perspective, Millet believed that humanity was condemned to unbearable suffering following the curse. Thus, the man and woman depict the expulsion from the Garden of Eden. The two peasants represent every person. The peasant’s faces are hidden and, therefore, they lack any individuality to depict their plight. In regular contemporary garb and depiction of poverty, the couple appears ordinary and ready to toil on the earth to make it productive. The painting is perhaps a tribute to pride and bravery of the countryside farmer who must toil to feed self. This painting is a reflection and symbol of the peasants, which could be a form of social protest.

From many works of Jean-François Millet, the laboring peasant farmer was his favorite. Regardless of Millet’s philosophical orientations, the rural peasants earned him allegations of a Socialist supporter. At the time of this work, Realism was not held in high regard, and Millet’s works stood out among the most questionable paintings of mid-1800s in France.

Many critics consider Millet’s work from different perspectives. From a social context, Millet is seen as a Socialist who advanced the agenda of peasant farmers but avoided the political controversy of the time. From a Marxist perspective, Millet’s artistic works depicted and challenged the predominant establishments and foundations of French society. The works of art uncover the Millet’s reaction to urban-industrial transformation following the Parisian mass exit. Thus, in showing various Millet’s works, these views demonstrate how different critics have diverse viewpoints on the works of the artist.

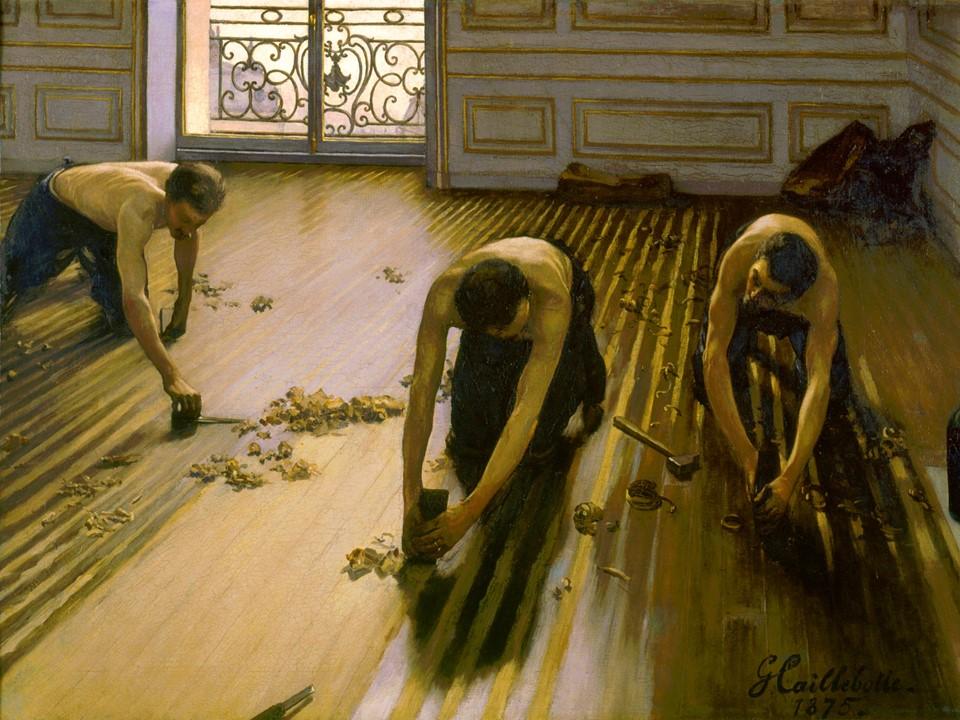

The Floor Scrapers by Gustave Caillebotte

The style of this work belongs to the Realism genre. For Gustave, the art establishment only considered peasants and farmers from the countryside as acceptable subjects in works of art, which highlighted the realism of working-class life. The Floor Scrappers painting is an artistic work, which portrays regular workers working diligently. The portrayal of the working class people in paintings was not new during the Realism period. However, while this painting was not exceptional, it differed from other past paintings that had solely focused on the hardship of the common laborers at the farms or countryside peasants. The Floor Scrappers portrays the reality of the urban working class and, thus, it was among the principal paintings to do so. It was observed that Caillebotte presented this work, but was rejected because its unrefined authenticity and some critics went so far as to claim that it obscene and offensive. Caillebotte was both baffled and irritated by their position and noted that displaying paintings at the Salon would not yield much in the future. Consequently, the artist chose to orient himself with another group of artists, who preferred his works. They created a movement of the Impressionists who were perplexed by the narrow perspectives of many scholars on paintings.

The masterpiece presented here is essentially a painting portraying men working hard. Here, one can observe three men scrapping the varnish off the floor of a new flat. There is neither a strong message nor is there a serious political depiction. The artist is just demonstrating men working diligently to complete a difficult work. As such, the painting made Caillebotte to be looked upon as a prominent painter among the most skilled French realist painters during the Realism period. It is striking to notice how the artist has portrayed the musculature of the upper arms of the laborers as they conduct their extremely difficult jobs on their knees and hands. Additionally, Caillebotte’s depiction of the laborers is enhanced by the light of the late evening streaming through the window at the balcony and brightens their backs. It takes viewers back to the period of Antiquity was when paintings were simple and striking. France, similar to England, had quite recently experienced the Industrial Revolution and with modernization came another social class that was named la classe ouvrière or common laborers and it was entirely different from the bourgeoisie. The laboring men one finds in Caillebotte’s painting may have been raised in the rural districts and consequently they were accustomed to debilitating and demanding work and had moved to the city to seek for wealth.

At the period of this artistic work, France was experiencing political and economic developments, and Paris was experiencing huge change as the regime of the day focused on renovation of the city, which was the colossal modernization of Paris as previously ordered by Napoleon. The project covered all vital features of urban planning, both in the middle of the co and in the encompassing locale: roads and streets, directions forced on exteriors of structures, open parks, sewers and water works, offices, and open landmarks. The arranging was impacted by many components, not the minimum of which was the city’s history of road insurgencies. This was a period of awesome changes and in a way, the artist needed to transform work and what had been already been rejected. Thus, Caillebotte needed to be acknowledged yet he was somewhat comparatively radical if this painting was considered. There is an awesome difference in colors utilized as a part of the depiction from the light blue walls to the dim tans of the floor and the men’s garments.

Edgar Degas, A Cotton Office, New Orleans, 1873

This painting, A Cotton Office in New Orleans by Edgar Degas was done in the period of Impressionist when painters were focused on ordinary subject matters and the overall visual effect is prominent than details. In this painting, Degas portrays his uncle Michel Musson’s cotton brokerage entity, which later collapsed following economic turmoil at the time and the emergence of large cotton firms. In the artistic painting, Musson is noted looking at raw cotton for its grade, while Degas’ bother Rene peruses a newspaper. One more sibling, Achille, supports himself close to a window wall at the left side, and including other colleagues, focus on their normal activities.

The painting presented a defining moment in his career as he moved from being a struggling, unrecognized artist to a well-known and financially stable painter because of the earning he got from the museum and Impressionist.

Following the failure of the artist to travel to Europe, he decided to paint this piece of art with the ultimate aim of offering it later to an English textile producer. However, the expectation of offering the art for sale was short-lived following a decrease in cotton and art markets. Nonetheless, the painting was eventually sold in the second exhibition.

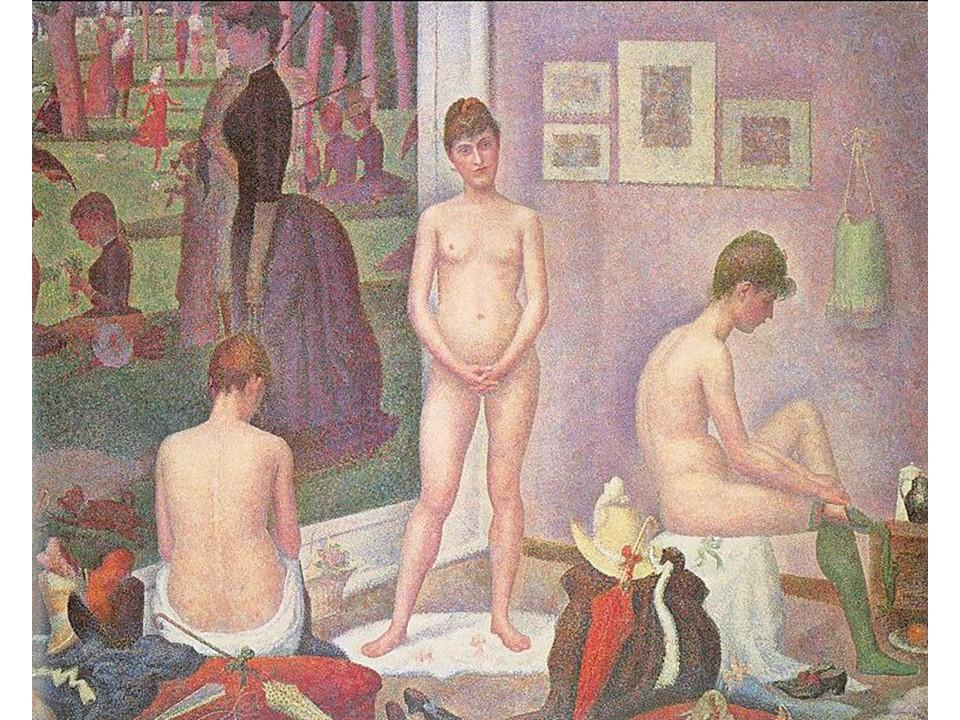

Georges Seurat (The Models/Les poseuses, 1886-88)

The Models/Les poseuses refers to the period of Post-Impressionism. This art movement advanced Impressionism, but dismissed its perceived weaknesses, such as worthlessness of the theme and poor structure. Here, the artist delineates three models (they are presumably a similar woman in various poses) during the time spent getting undressed to pose for the painting. The models stand before the previous work with their gear strewn around them, making the audience mindful of their nakedness and their status as women at work. The three models are seen from the three sides – front, side, and back, but the artist disperses any idea of a timeless mythological Greek mythology account by presenting contemporaneousness of the apparel that the models have removed additionally and through an ordinary routine of models removing their outfits to pose for the artists. In this sense, Seurat explores the body politics by presenting the three women as contemporary working class and he appears to dismiss the conventional idea that female nudity possesses both timeless and quintessentially natural.

Seurat’s work incorporates a considerable measure of pressure, falls between admired arts and current science in addition to popular culture and first class, high painting. Here, Seurat’s enthusiasm for the ideals of the past is obvious through works of obtained from various sources and incorporated to paint the three models.

Conclusion

In this essay, five pieces of art works have been explored, and they cover different periods (between 1850s and 1886s). Artists presented their works to reflect aspects of realism, Impressionism, and Post-Impressionism, and portray aspects of society as they had witnessed them.

Bibliography

Amley, Hollis Marie. The Evolution of Criticism on Jean-Francois Millet. PDF. NCSU Libraries, 2005.

Clark, Timothy James. The Absolute Bourgeois: Artists and Politics in France 1848-1851. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1982.

Harris, Beth, and Steven Zucker. Realism and Reality. Web.

Johnson, Jerah. “Degas and the Business of Art: A Cotton Office in New Orleans.” Louisiana History 36, no. 3 (1995): 345–7.

Nochlin, Linda. “Body politics: Seurat’s Poseuses.” Art in America 82, no. 3 (1994): 70-77.

Ten-Doesschate, Chu Petra. Nineteenth-century European Art. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2011.